THE VATICAN in WORLD POLITICS - Cont

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uneeveningseveralyearsago

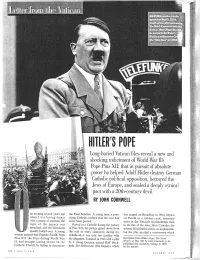

SUdfffiiUeraiKdiesavadio speechfinWay9,3934, »eariya3fearjafierannounce !Uie9leich£oncoRlati^3he Vatican.Aisei^flope^us )isseamed^SLIRetef^ Sa^caonVeconber ahe*»otyireaf'4Dfl9ra: 'i ' TlfraR Long-buried Vatican files reveal a new anc ; shocking indictment of World War IPs Jj; : - I • • H.t.-,. in n. ; Pope Pius XII: that in pursuit of absolute power he helped Adolf Hitler destroy German ^ Catholic political opposition, betrayed the Europe, and sealed a deeply cynica pact with a 20th-century devi!. BBI BY JOHN CORNWELL the Final Solution. A young man, a prac was staged on Broadway in 1964. depict UnewheneveningI wasseveralhavingyearsdinnerago ticing Catholic, insisted that the case had ed Pacelli as a ruthless cynic, interested with a group of students, the never been proved. more in the Vatican's stockholdings than topic of the papacy was Raised as a Catholicduring the papacy in the fate of the Jews. Most Catholics dis broached, and the discussion of Pius XII—his picture gazed down from missed Hochhuth's thesis as implausible, quickly boiled over. A young the wall of every classroom during my but the play sparked a controversy which woman asserted that Eugenio Pacelli, Pope childhood—I was only too familiar with Pius XII, the Pope during World War the allegation. It started in 1963 with a play Excerpted from Hitler's Pope: TheSeci-et II, had brought lasting shame on the by a young German named Rolf Hoch- History ofPius XII. bj' John Comwell. to be published this month byViking; © 1999 Catholic Church by failing to denounce huth. DerStellverti-eter (The Deputy), which by the author. VANITY FAIR OCTOBER 1999 having reliable knowl- i edge of its true extent. -

Katholisches Wort in Die Zeit 45. Jahr März 2014

Prof. Dr. Konrad Löw: Pius XII.: „Bleibt dem katholischen Glauben treu!“ 68 Gerhard Stumpf: Reformer und Wegbereiter in der Kirche: Klemens Maria Hofbauer 76 Franz Salzmacher: Europa am Scheideweg 82 Katholisches Wort in die Zeit 45. Jahr März 2014 DER FELS 3/2014 65 Formen von Sexualität gleich- Liebe Leser, wertig sind. Eine Vorgeschichte hat weiterhin die Insolvenz des kircheneigenen Unternehmens der Karneval ist in der katho- „Weltbild“. Das wirtschaftliche lischen Welt zuhause, wo sich Desaster ist darauf zurückzufüh- der Rhythmus des Lebens auch ren, dass die Geschäftsführung im Kirchenjahr widerspiegelt. zu spät auf das digitale Geschäft Die Kirche kennt eben die Natur gesetzt hat. Hinzu kommt die INHALT des Menschen und weiß, dass er Sortimentsausrichtung, die mit auch Freude am Leben braucht. Esoterik, Pornographie und sa- tanistischer Literatur, trotz vie- Papst Franziskus: Lebensfreude ist nicht gera- Das Licht Christi in tiefster Finsternis ....67 de ein Zeichen, das unsere Zeit ler Hinweise über Jahrzehnte, charakterisiert. Die zunehmen- keineswegs den Anforderungen Prof. Dr. Konrad Löw: : den psychischen Erkrankungen eines kircheneigenen Medien- Pius XII.: „Bleibt dem sprechen jedenfalls nicht dafür. unternehmens entsprach. Eine katholischen Glauben treu!“ .................68 „Schwermut ist die Signatur der Vorgeschichte hat schließlich die Gegenwart geworden“, lautet geistige Ausrichtung des ZDK Raymund Fobes: der Titel eines Artikels, der die- und der sie tragenden Großver- Seid das Salz der Erde ........................72 ser Frage nachgeht (Tagespost, bände wie BDKJ, katholische 1.2.14). Frauenverbände etc. Prälat Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Lothar Roos: Die Menschen erleben heute, Die selbsternannten „Refor- „Ein Licht für das Leben mer“ der deutschen Ortskirche in der Gesellschaft“ (Lumen fidei) .........74 dass sie mit verdrängten Prob- lemen immer mehr in Tuchfüh- ereifern sich immer wieder ge- Gerhard Stumpf: lung kommen. -

American Catholicism and the Political Origins of the Cold War/ Thomas M

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1991 American Catholicism and the political origins of the Cold War/ Thomas M. Moriarty University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Moriarty, Thomas M., "American Catholicism and the political origins of the Cold War/" (1991). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1812. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1812 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMERICAN CATHOLICISM AND THE POLITICAL ORIGINS OF THE COLD WAR A Thesis Presented by THOMAS M. MORI ARTY Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 1991 Department of History AMERICAN CATHOLICISM AND THE POLITICAL ORIGINS OF THE COLD WAR A Thesis Presented by THOMAS M. MORIARTY Approved as to style and content by Loren Baritz, Chair Milton Cantor, Member Bruce Laurie, Member Robert Jones, Department Head Department of History TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. "SATAN AND LUCIFER 2. "HE HASN'T TALKED ABOUT ANYTHING BUT RELIGIOUS FREEDOM" 25 3. "MARX AMONG THE AZTECS" 37 4. A COMMUNIST IN WASHINGTON'S CHAIR 48 5. "...THE LOSS OF EVERY CATHOLIC VOTE..." 72 6. PAPA ANGEL I CUS 88 7. "NOW COMES THIS RUSSIAN DIVERSION" 102 8. "THE DEVIL IS A COMMUNIST" 112 9. -

The Pius XII Controversy: John Cornwell, Margherita Marchione, Et Al

Consensus Volume 26 Article 7 Issue 2 Apocalyptic 11-1-2000 The iuP s XII controversy: John Cornwell, Margherita Marchione, et al Oscar Cole-Arnal Follow this and additional works at: http://scholars.wlu.ca/consensus Recommended Citation Cole-Arnal, Oscar (2000) "The iusP XII controversy: John Cornwell, Margherita Marchione, et al," Consensus: Vol. 26 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: http://scholars.wlu.ca/consensus/vol26/iss2/7 This Studies and Observations is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Consensus by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Pius XII Controversy: John Cornwell, Margherita Marchione, et. al. Oscar L. Cole-Arnal Professor of Historical Theology Waterloo Lutheran Seminary Waterloo, Ontario ew would dispute that Eugenio Pacelli, better known as Pope Pius XII, remains one of the most controversial figures of this Fcentury. Although his reign lasted twenty years (1939-1958), the debate swirls around his career as a papal diplomat in Germany from I 1917 to 1939 (the year he became pope) and the period of his papacy I i that overlapped with World War II. Questions surrounding his relation- ship with Hitler’s Third Reich (1933-1945) and his policy decisions with respect to the Holocaust extend far beyond the realm of calm historical research to the point of acrimonious polemics. In fact, virtually all the I studies which have emerged about Pius XII after the controversial play I The Deputy (1963) by Rolf Hochhuth range between histories with po- lemical elements to outright advocacy works for or against. -

Gottes Mächtige Dienerin Schwester Pascalina Und Papst Pius XII

Martha Schad Gottes mächtige Dienerin Schwester Pascalina und Papst Pius XII. Mit 25 Fotos Herbig Für Schwester Dr. Uta Fromherz, Kongregation der Schwestern vom Heiligen Kreuz, Menzingen in der Schweiz Inhalt Teil I Inhaltsverzeichnis/Leseprobe aus dem Verlagsprogramm der 1894–1929 Buchverlage LangenMüller Herbig nymphenburger terra magica In der Nuntiatur in München und Berlin Bitte beachten Sie folgende Informationen: Von Ebersberg nach Altötting 8 Der Inhalt dieser Leseprobe ist urheberrechtlich geschützt, Im Dienst für Nuntius Pacelli in München und Berlin 20 alle Rechte liegen bei der F. A. Herbig Verlagsbuchhandlung GmbH, München. Die Leseprobe ist nur für den privaten Gebrauch bestimmt und darf nur auf den Internet-Seiten www.herbig.net, Teil II www.herbig-verlag.de, www.langen-mueller-verlag.de, 1930–1939 www.nymphenburger-verlag.de, www.signumverlag.de und www.amalthea-verlag.de Im Vatikan mit dem direkt zum Download angeboten werden. Kardinalstaatssekretär Pacelli Die Übernahme der Leseprobe ist nur mit schriftlicher Genehmigung des Verlags Besuchen Sie uns im Internet unter: Der vatikanische Haushalt 50 gestattet. Die Veränderungwww d.heer digitalenrbig-verlag Lese.deprobe ist nicht zulässig. Reisen mit dem Kardinalstaatssekretär 67 »Mit brennender Sorge«, 1937 85 © 2007 by F.A. Herbig Verlagsbuchhandlung GmbH, München Alle Rechte vorbehalten Umschlaggestaltung: Wolfgang Heinzel Teil III Umschlagbild: Hans Lehnert, München 1939–1958 und dpa/picture-alliance, Frankfurt Lektorat: Dagmar von Keller Im Vatikan mit Papst Pius XII. Herstellung und Satz: VerlagsService Dr. Helmut Neuberger & Karl Schaumann GmbH, Heimstetten Judenverfolgung, Hunger und Not 94 Gesetzt aus der 11,5/14,5 Punkt Minion Das päpstliche Hilfswerk – Michael Kardinal Drucken und Binden: GGP Media GmbH, Pößneck Printed in Germany von Faulhaber 110 ISBN 978-3-7766-2531-8 Mächtige Hüterin 146 Teil IV 1959–1983 Oberin am päpstlichen nordamerikanischen Priesterkolleg in Rom Der vatikanische Haushalt Leben ohne Papst Pius XII. -

NEW TITLES in BIOETHICS Annual Cumulation Volume 19,1993

NATIONAL REFERENCE CENTER FOR BIOETHICS LITERATURE THE JOSEPH AND ROSE KENNEDY INSTITUTE OF ETHICS GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY, WASHINGTON, DC 20057 NEW TITLES IN BIOETHICS Annual Cumulation Volume 19,1993 (Includes Syllabus Exchange Catalog) Lucinda Fitch Huttlinger, Editor ISSN 0361-6347 NEW TITLES IN BIOETHICS is published four times per year (quarterly) by the National Reference Center for Bioethics Literature, Kennedy Institute of Ethics. Annual Cumulations are published in the following year as a separate publication. NEW TITLES IN BIOETHICS is a listing by subject of recent additions to the National Reference Center’s collection. (The subject clas sification scheme is reproduced in full with each issue; it can also be found at the end of the cumulated edition.) With the exception of syllabi listed as part of our Syllabus Exchange program, and documents in the section New Publica tions from the Kennedy Institute of Ethics, materials listed herein are not available from the National Reference Center, but from the publishers listed in each citation. Subscription to NEW TITLES IN BIOETHICS is $20.00 per calendar year in the U.S., Canada, and Mexico, and $30.00 elsewhere. Back volumes are avail able at $12.00 per volume (subscribers) and $15.00 per volume (non-sub scribers) in the U.S., Canada and Mexico, $17.00 per volume (subscribers) and $20.00 per volume (non-subscribers) elsewhere. All orders must be prepaid. Associate and institutional members of the Kennedy Institute of Ethics receive NEW TITLES IN BIOETHICS (quarterly issues) as part of their membership benefits. Inquiries regarding the membership program should be addressed to: Irene McDonald Kennedy Institute of Ethics Georgetown University Washington, DC 20057 (202) 687-8099. -

The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930–1965 Ii Introduction Introduction Iii

Introduction i The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930–1965 ii Introduction Introduction iii The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930 –1965 Michael Phayer INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS Bloomington and Indianapolis iv Introduction This book is a publication of Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA http://www.indiana.edu/~iupress Telephone orders 800-842-6796 Fax orders 812-855-7931 Orders by e-mail [email protected] © 2000 by John Michael Phayer All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and re- cording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of Ameri- can University Presses’ Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Perma- nence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Phayer, Michael, date. The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930–1965 / Michael Phayer. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-253-33725-9 (alk. paper) 1. Pius XII, Pope, 1876–1958—Relations with Jews. 2. Judaism —Relations—Catholic Church. 3. Catholic Church—Relations— Judaism. 4. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945) 5. World War, 1939– 1945—Religious aspects—Catholic Church. 6. Christianity and an- tisemitism—History—20th century. I. Title. BX1378 .P49 2000 282'.09'044—dc21 99-087415 ISBN 0-253-21471-8 (pbk.) 2 3 4 5 6 05 04 03 02 01 Introduction v C O N T E N T S Acknowledgments ix Introduction xi 1. -

Session 3: Catholicism Before and After 1933 Four Things to Keep in Mind

Session 3: Catholicism before and after 1933 Four things to keep in mind • People didn’t have our foresight; genocidal murder was not on the horizon. • A mindset of Catholic leadership dominated by societas perfecta ecclesiology. • Second-class citizenship and the enduring memory of the Kulturkampf. • The bishops’ disgust with both the political and cultural liberalism of the Weimar Republic. • German Catholicism was part of an international church. “Political Catholicism”: Center Party and Bavarian Peoples Party as bulwark of the Weimar Republic • Third largest party for most of the Republic. • Integral element, along with the SPD, of Weimar coalitions. • Much criticized by Rome for its coalitions with the anti- clerical and socialist SPD. • Party chair after 1928 was a cleric, canon law expert Msgr. Ludwig Kaas. • After Brüning becomes chancellor in March 1930, a rightward turn in its politics. Papacy and German Catholicism: Vatican concordat policy • Historic fear that German Catholicism would go “national”. • Recognition of new (1917) code of canon law, esp. regarding appointment of bishops. • Eugenio Pacelli as Vatican nuncio to the Republic (1921-29), then secretary of state under Pius XI (1930-39). • Protection of aid to schools and state subsidies for the Church. • Concordat policy: no Reich policy, but Bavaria (1924), Prussia (1929), and Baden (1932). Lateran Accords (1929): Settling the Roman Question with Mussolini • Vatican City becomes a sovereign entity and a large cash settlement. • Catholicism the only religion of the Italian state. • Sturzo’s Catholic “Italian Popular Party” dissolved – Hitler takes notice. • Pius XI’s preference for Catholic Action rather than Catholic political parties. -

Manual De Historia De La Iglesia

j »fWtr v J\*WH> J *J^vni MU J\XUUCn MANUAL DE HISTORIA DE LA IGLESIA SECCIÓN DE HISTORIA BIBLIOTECA HERDER HUBERT JEDIN y KONRAD REPGEN SECCIÓN DE HISTORIA VOLUMEN 170 MANUAL DE HISTORIA DE LA IGLESIA MANUAL DE HISTORIA DE LA IGLESIA TOMO NOVENO IX LA IGLESIA MUNDIAL DEL SIGLO XX Publicado bajo la dirección de HUBERT JEDIN y KONRAD REPGEN Por GABRIEL ADRIÁNYI - PIERRE BLET JOHANNES BOTS - VIKTOR DAMMERTZ - ERWIN GATZ ERWIN ISERLOH - HUBERT JEDIN - GEORG MAY JOSEPH METZLER - LUIGI MEZZARDI FRANCO MOLINARI - KONRAD REPGEN - LEO SCHEFFCZYK MICHAEL SCHMOLKE - BERNHARD STASIEWSKI ANDRÉ TIHON - NORBERT TRIPPEN - ROBERT TRISCO LUDWIG VOLK - WILHELM WEBER PAUL-LUDWIG WEINACHT BARCELONA BARCELONA EDITORIAL HERDER EDITORIAL HERDER 1984 1984 Versión castellana de MARCIANO VIIXANUEVA, de la obra Handbuch der Kirchengeschichle, tomo vil, publicado bajo la dirección de HUBERT JEDIN y KONRAD REPGEN, por GABRIEL ADRIÁNYI, FIERRE BLET, JOHANNES BOTS, VIKTOR DAMMERTZ, ERWIN GATZ, ERWIN, ISERLOH, HUBERT JEDIN, GEORO MAY, JOSEPH METZLER, LUIGI MEZZARDI, FRANCO MOLINARI, KONRAD REPOEN, LEO SCHEFFCZYK, MICHAEL SCHMOLKE, BERNHARD STASIEWSKI, ANDRÉ TIHON, NORBERT TRIPPEN, ROBERT TRISCO, LUDWIG VOLK, WILHELM WEBER y PAUL-LI DWIG WFINACHT, Verlag Herder KG, Friburgo de Brisgovia 1979 ÍNDICE índice de siglas 11 Prólogo 17 PARTE PRIMERA: LA UNIDAD INSTITUCIONAL DE LA IGLESIA I. Estadística 23 Estadística de la población mundial — Estadística de las religiones mundiales — Porcentaje de los católicos . 23 Estadística de la población mundial de 1914 a 1965 . 24 Estadística de las religiones mundiales de 1914 a 1965 . 28 El desplazamiento del mundo cristiano hacia el sur . 33 Organización general de la Iglesia de 1914 a 1970 .. -

24. the Exile and Its Conclusion

24. The Exile and its Conclusion The time of the founder’s exile ended in a very dramatic way in the Autumn of 1965. For the founder and the Schoenstatt Family it was in very truth a “miracle of the Holy Night.” A few days afterwards, as early as 3 January 1966, Fr Kentenich talked about these events in a series of con- ferences for Schoenstatt Priests in the diocese of Münster. This talk is particularly valuable because it reflects in a very lively manner what the founder himself had ex- perienced. So when reading the text we will gladly take into the bargain the interruptions in the line of thought, insertions, and reflections that read like footnotes. Critical historical research could possibly correct various details in the account. Things happened so fast and were tremendously dramatic. The personal ex- periences of the founder, which clearly reflect his inner distance from events and circumstances in Rome, as well as his personal involvement, keep their special value and are absolutely valid in the way they describe the basic course of events. In order to provide a better over - view, a few key dates are provided here: 22 Oct. 1951 Fr Kentenich had to leave Schoenstatt. He arrived in Milwaukee on 21 June 1952 Frank and open letter to Fr [Wilhelm] Möhler, Superior General of the Pallottines, which was answered by harsh measures of the Holy Office, including an ecclesiastical penalty: 31 Oct. 1961 Fr Kentenich had to undertake a private retreat and could not celebrate Holy Mass for three days. 11 Oct. -

Universidade Estadual De Campinas Instituto De Filosofia E Ciências Humanas

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS INSTITUTO DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS GABRIEL RIBEIRO BARNABÉ SUMMI PONTIFICATUS As Relações Internacionais da Santa Sé sob Pio XII TESE DE DOUTORADO APRESENTADA AO INSTITUTO DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DA UNICAMP PARA OBTENÇÃO DO TÍTULO DE DOUTOR EM FILOSOFIA. PROF. DR. ROBERTO ROMANO DA SILVA ESTE EXEMPLAR CORRESPONDE À VERSÃO FINAL DA TESE DEFENDIDA PELO ALUNO GABRIEL RIBEIRO BARNABÉ, E ORIENTADA PELO PROF. DR. ROBERTO ROMANO DA SILVA, CPG, EM 09/06/2011. CAMPINAS, 2011 i FICHA CATALOGRÁFICA ELABORADA PELA BIBLIOTECA DO IFCH - UNICAMP Bibliotecária: Sandra Aparecida Pereira CRB nº 7432 Barnabé, Gabriel Ribeiro B252s Summi Pontificatus: as relações internacionais da Santa Sé sob Pio XII / Gabriel Ribeiro Barnabé. - - Campinas, SP : [s. n.], 2011. Orientador: Roberto Romano da Silva Tese (doutorado) - Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. 1.Pio XII, Papa, 1876-1958. 2.Relações internacionais. 3.Ciência política - Filosofia. 4. Igreja e Estado. 5. Ética. 6. Igreja Católica. 7. Santa Sé - Relações exteriores. I. Silva, Roberto Romano da. II. Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas. III. Título. Título em inglês: Summi Pontificatus: the international relation of the Holy See under Pius XII Palavras chaves em inglês (keywords): International relations Political science - Philosophy Church and State Ethics Catholic Church Santa Sé - Foreign relations Área de Concentração: Filosofia Titulação: Doutor em Filosofia Banca examinadora: Roberto Romano da Silva, Oswaldo Giacoia Junior, Pedro L. Goergen, Celso Antonio de Almeida, Romualdo Dias Data da defesa: 09-06-2011 Programa de Pós-Graduação: Filosofia ii iv DEDICATÓRIA À Graziela e Gabriela. -

![Thomas Brechenmacher (Hrsg.): Das Reichskonkordat 1933. Forschungsstand, Kontroversen, Dokumente, Paderborn [U. A.] 2007](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0354/thomas-brechenmacher-hrsg-das-reichskonkordat-1933-forschungsstand-kontroversen-dokumente-paderborn-u-a-2007-4430354.webp)

Thomas Brechenmacher (Hrsg.): Das Reichskonkordat 1933. Forschungsstand, Kontroversen, Dokumente, Paderborn [U. A.] 2007

Thomas Brechenmacher (Hrsg.): Das Reichskonkordat 1933. Forschungsstand, Kontroversen, Dokumente, Paderborn [u. a.] 2007. (= Veröffentlichungen der Kommission für Zeitgeschichte, Reihe B: Forschungen, Bd. 109) The present volume originated in a Giornate di Studi organized by the publisher at the German Historical Institute in Rome on 17 June 2004. Under the title »The End of Political Catholicism in Germany in 1933 and the Holy See: Enabling Law, Reich Concordat and Dissolution of the Center Party,« the participants were called upon to debate the »state of research, scholarly perspectives, and new sources 25 years after the Scholder-Repgen controversy.« 1 The immediate catalyst for reexamining these questions of the Center Party’s demise and the beginnings of the Reich Concordat, questions that had long been quiescent, was the opening of files pertaining to Germany from the papacy of Pius XI (1922–1939) by the Vatican Secret Archive in February 2003. An important collection of sources from one of the main historical actors, The Holy See – to which only selected individuals had previously been given access – was now open to the wider scholarly community. That alone would have been reason enough to ask both established and younger scholars of recent church history whether they expected the newly opened Vatican files to shed new light on the »question of the Reich Concordat« or had perhaps already gained new understanding as a result of their work with these sources. The fact that around the same time other important archives and collections were made accessible, or were being prepared for opening, provided further impetus for a scholarly »stock-taking.« In late 2002, the archive of the Archdiocese of Munich and Freising made available the papers of Archbishop Michael Cardinal Faulhaber.