An Inspector Calls and J B Priestley's Political Journey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Inspector Calls Is Recommended for the Artistic Team Students in Grade 8 Director……………………….JIM MEZON and Higher

An Inspector by J.B. Priestley Calls ONNECTIONS Shaw Festival CStudy Guide The Shaw Story 2 The Players 3 The Story 4 Who’s Who 5 The Playwright 6-7 Director’s Notes 8 Designer’s Notes 9 Production History 10 World of the Play 11-15 Did You Know? 16 Say What? 17 Sources 18 Activities 18-29 Response Sheet 30 THE SHAW STORY MANDATE The Shaw Festival is the only theatre in the world which exclusively focuses on plays by Bernard Shaw and his contemporaries, including plays written or about the period of Shaw’s lifetime (1856 – 1950). The Shaw Festival’s mandate also includes: • Uncovered Gems – digging up undiscovered theatrical treasures, or plays which were considered major works when they were written but which have since been unjustly neglected • American Classics – we continue to celebrate the best of American theatre • Musicals – rarely-performed musical treats from the period of our mandate are re- discovered and returned to the stage WHAT MAKES • Canadian Work – to allow us to hear and promote our own stories, our own points SHAW SPECIAL of view about the mandate period. MEET THE COMPANY — OUR ENSEMBLE • Our Actors: All Shaw performers contribute to the sense of ensemble, much like the players in an orchestra. Often, smaller parts are played by actors who are leading performers in their own right, but in our “orchestra,” they support the central action helping to create a density of experiences that are both subtle and informative. • Our Designers: Every production that graces the Shaw Festival stages is built “from scratch,” from an original design. -

Download Date 03/10/2021 02:12:06

Alive and Kicking! J.B. Priestley and the University of Bradford Item Type Article Authors Cullingford, Alison Citation Cullingford A (2016) Alive and Kicking! J.B. Priestley and the University of Bradford. The Journal of the J.B. Priestley Society.17: 46-55. Rights (c) 2016 Cullingford A. Full-text reproduced with author's permission. Download date 03/10/2021 02:12:06 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/11433 The University of Bradford Institutional Repository http://bradscholars.brad.ac.uk This work is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our Policy Document available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this work please visit the publisher’s website. Access to the published online version may require a subscription. Citation: Cullingford A (2016) Alive and Kicking! J.B. Priestley and the University of Bradford. The Journal of the J.B. Priestley Society.17: 46-55. Copyright statement: © 2016 Cullingford A. Full-text reproduced with author’s permission. JBP and the Uni article Bradford’s University celebrates its 50th anniversary in 2016. What better time therefore to share some stories of the links between the University and the city’s famous son? New university, old story The University of Bradford came into existence on the 18 October 1966 when the Queen signed its Royal Charter. J.B. Priestley was then 72. The University was not one of the new ‘plateglass’ universities that sprang up on greenfield sites during the 1960s boom in higher education, such as York, Sussex and East Anglia. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Victoria's Heyday by J.B. Priestley Victoria's Heyday by J.B

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Victoria's Heyday by J.B. Priestley Victoria's Heyday by J.B. Priestley. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 660d1f96a8de2bdd • Your IP : 116.202.236.252 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Bibliography. 1931 The Good Companions (adaption with Edward Knoblock) 1932 Dangerous Corner 1933 The Roundabout 1934 Laburnum Grove 1934 Eden End 1935 Duet in Floodlight 1936 Cornelius 1936 Spring Tide (with George Billam) 1936 Bees on the Boatdeck 1937 Time and the Conways 1937 Mystery at Greenfingers 1937 I Have Been Here Before 1937 People at Sea 1938 Music at Night (published 1947) 1938 When We Are Married 1939 Johnson Over Jordan 1940 The Long Mirror (published 1947) 1942 Good Night Children 1944 They Came to a City 1944 Desert Highway 1945 How Are They at Home? 1946 Ever Since Paradise 1947 An Inspector Calls 1947 The Rose and Crown 1948 The Linden Tree 1948 The Golden Fleece 1948 The High Toby (for Toy Theatre) 1949 The Olympians (opera, music by Arthur Bliss) 1949 Home is Tomorrow 1950 Summer Day’s Dream 1950 Bright Shadow 1952 Dragon’s Mouth (with Jacquetta Hawkes) 1953 Treasure on Pelican 1953 Try It Again 1953 Private Rooms 1953 Mother’s Day 1954 A Glass of Bitter 1955 Mr Kettle and Mrs Moon 1956 Take the Fool Away 1958 The Glass Cage 1963 The Pavilion of Masks 1964 A Severed Head (with Iris Murdoch) 1974 The White Countess (with Jacquetta Hawkes) FICTION. -

JB Priestley

CHARLES PARKHURST RARE BOOKS & AUTOGRAPHS PRESENTS J. B. PRIESTLEY A COLLECTION J. B. Priestley (13 September 1894 – 14 August 1984) Charles Parkhurst Rare Books & Autographs 7079 East 5th Avenue Scottsdale, AZ 85251 480.947.3358 fax- 480.947.4563 [email protected] www.parkhurstrarebooks.com All items are subject to prior sale. We accept Visa, Mastercard, Amex, Discover, Check, Wire Transfer, Bank Check or Money Orders in US Funds. Personal checks must clear prior to shipment. Prices are net. Institutions billed. Shipping and insurance are extra and will be billed at cost according to customer's shipping preference with tracking availability. For approximate shipping cost by weight, destination and approximate travel time please contact us. All items sent on approval and have a ten day return privilege. Please notify us prior to returning. All returns must be properly packaged and insured. All items must be returned in same condition as sent. J.B. Priestley 1894-1984. Author, novelist, playwright, essayist, broadcaster, scriptwriter, social commentator and man of letters whose career straddles the 20th century. LOST EMPIRES. London: Heinemann, (1965). First edition. 308 pp., bound in brown cloth spine lettering silver, near fine in unclipped very good dust jacket showing minor wear. FESTIVAL AT FARBRIDGE. Melbourne: William Heinemann, Ltd., (1951). First Australian edition. 593 pp., bound in red cloth, spine lettering black, near fine in very good unclipped pictorial dust jacket by Eric Fraser with a minor wear to head and a touch of red bleed through from cloth and a couple of small closed edge tears to rear panel. THE CARFITT CRISES ad two other stories. -

Angel Pavement John Boynton Priestley

Министерство образования Российской Федерации Самарский государственный университет Кафедра английской филологии Angel Pavement John Boynton Priestley Методические указания по домашнему чтению для студентов 4 курса специальности «Английский язык и литература» Самара, 2003 Методические указания предназначены для самостоятельной работы студентов 4 курса специальности «Английский язык и литература» при подготовке к занятиям по домашнему чтению с книгой Дж. Б. Пристли «Улица Ангела». Указания включают биографическую справку об авторе и секции, каждая из которых предлагает выражения и фразеологические единицы для активного усвоения, упражнения, направленные на развитие языковых и речевых умений и навыков, а также вопросов и заданий дискуссионного характера. Наряду с заданиями коммуникативной направленности предлагаются также упражнения по лингвистическому анализу текста. Задания помогут студентам самостоятельно подготовиться к обсуждению основных проблем книги, поступков героев, их характеристик, интересных эпизодов, а также выразительных средств и стилистических приемов автора. В разделе Suggested topics дается примерный перечень тем, рекомендуемых для заключительного обсуждения книги. Методические указания состоят из 12 секций, каждая из которых рассчитана на 3 часа аудиторной и 4 часа самостоятельной работы. Задания рекомендуется выполнять выборочно, в зависимости от целей занятия и уровня подготовки студентов. Составители: ст. препод. Соболева Л. П., доц. Максакова С. П, доц. Дементьева Н. Я. Отв. редактор: зав. кафедрой английской филологии, проф. Харьковская А. А. Рецензент: кандидат педагогических наук, доцент кафедры иностранных языков Самарской экономической академии Подковырова В. В. 2 Priestley, J(ohn) B(oynton) Priestley, John Boynton was born in 1894, September 13, Bradford, Yorkshire, England and died in 1984, August 14, Alveston, near Stratford-upon-Avon, (Warwickshire). He is a British novelist, playwright, and essayist, noted for his varied output and his ability for shrewd characterization. -

Gender Sensitization in “An Inspector Calls”

International Journal of Applied Research 2018; 4(11): 237-239 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Gender Sensitization in “An Inspector Calls”: A Impact Factor: 5.2 IJAR 2018; 4(11): 237-239 Feminine Gendering Portrait of Social Landscape by J www.allresearchjournal.com Received: 29-08-2018 B Priestley Accepted: 15-10-2018 Rajesh Kumar Rajesh Kumar Research Scholar, Department Of English, LN Mithila University, Abstract Kameshwarnagar, Amidst in cultural landscape of England, Priestley in “An Inspector Calls”, sternly advocates about the Darbhanga, Bihar, India idea of feminine-gendering-landscape in pre-war British society. Through the massive representation of feminine characters of the play, he tends to open the reality of white-skinned-men of the society who as per patriarchal or men-gendered attitudes how suppress the women in the pre-war British society. “An Inspector Calls” set in 1912, amidst cultural landscape of Britain, a time when there was a class divide and gender sensitization and especially feminine-gendering who expected to know their position and place in provincial or metropolitan landscape in British society that is evident from the doom character of the play-Eva Smith alias Daisy Renton. So, Priestley explores the idea of gender discrimination through Mr. Arthur Birling, Gerold Croft and Eric birling in one side and Sybil Birling, Sheila Birling with especial attention on Eva Smith by the plaint Goole on other side. Keywords: cultural landscape, feminine-gendering, social landscape, metropolitan landscape, provincial landscape, gender discrimination Introduction The three act play, “An Inspector Calls” is a such type of work in which the playwright present a gender sensitive case with his stylistic way of writings in which male lust and sexual exploitation of the weak by the powerful white-skinned British- also a call by the millions of British mouth to English society. -

The Project Gutenberg Ebook of Getting Married, By

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Getting Married, by our marriage law is inhuman and unreasonable to the George Bernard Shaw point of downright abomination, the bolder and more rebellious spirits form illicit unions, defiantly sending This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost cards round to their friends announcing what they have and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may done. Young women come to me and ask me whether I copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the think they ought to consent to marry the man they have Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or decided to live with; and they are perplexed and online at www.gutenberg.org astonished when I, who am supposed (heaven knows why!) to have the most advanced views attainable on the Title: Getting Married subject, urge them on no account to compromize themselves without the security of an authentic wedding Author: George Bernard Shaw ring. They cite the example of George Eliot, who formed an illicit union with Lewes. They quote a saying Release Date: May, 2004 [EBook #5604] This file was attributed to Nietzsche, that a married philosopher is first posted on July 20, 2002 Last Updated: April 10, ridiculous, though the men of their choice are not 2013 philosophers. When they finally give up the idea of reforming our marriage institutions by private enterprise Language: English and personal righteousness, and consent to be led to the Registry or even to the altar, they insist on first arriving at *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG an explicit understanding that both parties are to be EBOOK GETTING MARRIED *** perfectly free to sip every flower and change every hour, as their fancy may dictate, in spite of the legal bond. -

RLT Script Catalogue in Play Order As at 2009

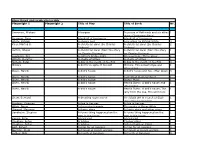

Plays listed alphabetically by title Playwright 1 Playwright 2 Title of Play Title of Book No. A Doneman, Michael A bargain In praise of flatheads and six other 1 plays (Classroom Plays) Freeman, Dave A bedfull of foreigners A bedfull of foreigners 1 White, Patrick A cheery soul Four plays by Patrick White 3 King, Martha B. A christmas carol (by Charles A christmas carol (by Charles 2 Dickens) Dickens) Sutton, Shaun A christmas carol (from the story A christmas carol (from the story 1 by Charles Dickens) by Charles Dickens) Lawrence, DH A collier's Friday night DH Lawrence: Three plays 1 Wright, Dorothy A cradle of willow A cradle of willow 1 Nichols, Peter A day in the death of Joe Egg A day in the death of Joe Egg 3 Moliere A doctor in spite of himself Moliere: The misanthrope and 1 other plays Ibsen, Henrik A doll's house A doll's house and two other plays 3 Ibsen, Henrik A doll's house Four great plays by Ibsen 1 Ibsen, Henrik A doll's house Ibsen: Plays 1 Ibsen, Henrik A doll's house Henrik Ibsen: A doll's house and 1 other plays Ibsen, Henrik A doll's house Henrik Ibsen: A doll's house, The 1 lady from the sea, The wild duck Shaw, Bernard A dressing room secret The black girl in search of God: 1 and some lesser plays Feydeau, Georges A flea in her ear A flea in her ear 1 Wilde, Oscar A florentine tragedy The works of Oscar Wilde 1 Stewart, Maureen A frosty story A frosty story and other plays 1 Sondheim, Stephen A funny thing happened on the A funny thing happened on the 1 way to the forum way to the forum Kenna, Peter A hard god A hard god 2 Chekhov, Anton A jubilee Chehov plays 1 Chekhov, Anton A jubilee Anton Chekhov: Plays 1 Bolt, Robert A man for all seasons A man for all seasons 3 Gorman, Clem A manual of trench warfare A manual of trench warfare 1 Larbey, Bob A month of Sundays A month of Sundays 3 Plays listed alphabetically by title Playwright 1 Playwright 2 Title of Play Title of Book No. -

Stories of the Past: Viewing History Through Fiction

Stories Of The Past: Viewing History Through Fiction Item Type Thesis or dissertation Authors Green, Christopher Citation Green, C. (2020). Stories Of The Past: Viewing History Through Fiction (Doctoral dissertation). University of Chester, UK. Publisher University of Chester Rights Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Download date 04/10/2021 08:03:20 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/623069 STORIES OF THE PAST: VIEWING HISTORY THROUGH FICTION Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Chester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Christopher William Green January 2020 Frontispiece: Illustration from the initial serialisation of Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D'Urbervilles.1 1 Thomas Hardy, 'Tess of the D’Urbervilles', The Graphic, August 29th, 1891. ii The material being presented for examination is my own work and has not been submitted for an award of this or another HEI except in minor particulars which are explicitly noted in the body of the thesis. Where research pertaining to the thesis was undertaken collaboratively, the nature and extent of my individual contribution has been made explicit. iii iv Abstract This thesis investigates how effective works of fiction are, through their depictions of past worlds, in providing us with a resource for the study of the history of the period in which that fiction is set. It assesses past academic literature on the role of fiction in historical understanding, and on the processes involved in the writing, reading, adapting, and interpreting of fiction. -

{PDF EPUB} Bright Day by JB Priestley

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Bright Day by J.B. Priestley Bright Day by Priestley. About this Item: Great Northern Books 05/10/2006, 2006. Condition: Very Good. Shipped within 24 hours from our UK warehouse. Clean, undamaged book with no damage to pages and minimal wear to the cover. Spine still tight, in very good condition. Remember if you are not happy, you are covered by our 100% money back guarantee. Seller Inventory # 6545-9781905080182. Bright Day: A Rediscovering Book (60th Anniversary Edition) J.B. Priestley. Published by Great Northern Books Ltd 2006 (2006) Quantity available: 1. From: MusicMagpie (Stockport, United Kingdom) About this Item: Great Northern Books Ltd 2006, 2006. Condition: Very Good. 1616769818. Seller Inventory # U9781905080182. Bright Day. J. B. Priestley. Published by The Reprint Society, London (1948) Quantity available: 1. From: Redruth Book Shop (Cornwall, United Kingdom) About this Item: The Reprint Society, London, 1948. Hardcover. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Good condition hardback no DJ. Blue boards showing title etc clearly on spine in gilt lettering on a black background. 368 pages good and clean with clear print. Feint spots of foxing on edge of pages, no previous names. Seller Inventory # 019566. Bright Day (Rediscovering Priestley) J. B. Priestley. Published by Great Northern Books Ltd (2006) Quantity available: 1. From: Brit Books (Milton Keynes, United Kingdom) About this Item: Great Northern Books Ltd, 2006. Hardcover. Condition: Used; Good. **Simply Brit** Shipped with Premium postal service within 24 hours from the UK with impressive delivery time. We have dispatched from our book depository; items of good condition to over ten million satisfied customers worldwide. -

Musical Diaspora in the Works of J.B. Priestley Impact Factor: 8.4 IJAR 2020; 6(10): 853-855 Received: 08-08-2020 Dr

International Journal of Applied Research 2020; 6(10): 853-855 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Musical Diaspora in the works of J.B. Priestley Impact Factor: 8.4 IJAR 2020; 6(10): 853-855 www.allresearchjournal.com Received: 08-08-2020 Dr. Rajesh Kumar Accepted: 11-09-2020 Abstract Dr. Rajesh Kumar However the elderly author was underselling himself. Priestley, was an important figure in twentieth Lecturer, Dept. of English century British intellectual life, wrote widely about music, displayed a detailed knowledge and RNP College, Pandaul understanding of classical music, and some more popular forms. Music played an important role in key Madhubani, Bihar, India novels, plays and non-fiction, often acting as a way of unleashing or illustrating human potential, or at the other end of the scale signifying human weakness. And Priestley wrote well about music too, bringing a novelist’s touch to the subject. There are various investigations on J.B. Priestley's life and work including appraisals of his books, social and political compositions and commitment to English culture. A portion of these examinations have remarked on Priestley and scene, particularly his connection to Bradford and provincial Yorkshire. Keywords: Classical, Music, Novel, Play, Non-fiction, Bradford, Yorkshire. Introduction J.B. Priestley had an incredible enthusiasm for music. Priestley's previously paid distribution was a 'topical production' Secrets of the Ragtime King, distributed in London Opinion on 12 December 1912. He got a guinea in installment and furthermore picked up the valuation for his dad who, while no master on jazz, was glad for his child's appearance in print. -

The Casualty Estimate for World War I, Both Military and Civilian, Was Over 40 Million – 20 Million Deaths and 21 Million Wounded

The casualty estimate for World War I, both military and civilian, was over 40 million – 20 million deaths and 21 million wounded. This includes 9.7 million military deaths and about 10 million civilian deaths. The Entente Powers lost more than 5 million soldiers and the Central Powers about 4 million. Then just a few short years later, World War II began, and racked up an even more impressive list; roughly 72 million. The civilian toll was around 47 million, including 20 million deaths due to war-related famine and disease. So it was a stunned and exhausted world that received John Boynton Priestley’s newest play, AN INSPECTOR CALLS. BY NEIL MUNRO Priestley by the end of the war was already a figure of some renown. His novel The Good Companions had become world famous, and his voice had become second in popularity to none other than Winston Churchill. Priestley wrote and delivered a personal view of the war for BBC Radio, chronicling the trials and tribulations of the ordinary working man and woman. The carnage, the courage, not to mention the optimism of the English people, seemed to need the popularity of an ordinary voice (rather than that of a professional politician) to soothe the daily wounds inflicted by Hitler’s buzz bombs and the massive battles being fought overseas. 10 Shaw Magazine / Spring 2008 Benedict Campbell, who will play Inspector Goole in the 2008 production of AN INSPECTOR CALLS (Photo by Shin Sugino). 11 This kind of destruction on such a grand scale Priestley wanted to write a play that focused on the profoundly affected Priestley’s views of both socialism terrible problems that could develop between people and and capitalism.