Using Narrative Picture Books to Build Awareness of Expository Text Structure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smith Newton Coyotes Royals

PAGE 8: SPORTS PRESS & DAKOTAN n WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 12, 2015 SCOREBOARD AREA CALENDAR Brianne (Vette) Edwards surgery practice. Coyotes (2001-04) (Conley 1-0), 3:10 p.m. Wednesday, August 12 Am Jam at CC of Sioux Falls BASEBALL Oakland (Brooks 1-0) at Toronto BASEBALL, AMATEUR State SOCCER, WOMEN’S USD at Edwards, who came to USD from Nancy McCahren (special S.D. CLASS B AMATEUR TOURN. (Buehrle 12-5), 6:07 p.m. Tourn. at Mitchell (Menno vs. Nebraska (exhibition, 7 p.m.) FROM PAGE 7 Spearfish, S.D., is an 11-time national Aug. 5-16 at Mitchell Atlanta (Wisler 5-2) at Tampa Bay Larchwood, 8 p.m., KVHT-FM) SOCCER, BOYS’ Watertown qualifier, a seven-time All-American, contributor) (Odorizzi 6-6), 6:10 p.m. at YHS (4 p.m.) McCahren has served USD for SECOND ROUND Thursday, August 13 and the 2004 national champion in the Sunday, Aug. 9 N.Y. Yankees (Sabathia 4-8) at BASEBALL, AMATEUR State SOCCER, BOYS’ JV Water- is now part owner of the company. He more than 50 years. After graduating in Canova 8, Lennox Only One 1 Cleveland (Salazar 9-6), 6:10 p.m. Tourn. at Mitchell town at YHS (6 p.m.) and his wife, Abbey, celebrated their first heptathlon. She led South Dakota to the Detroit (Da.Norris 2-2) at Kansas Watertown 1957 and earning her master’s degree Akron 3, Garretson 2 Friday, August 14 SOCCER, GIRLS’ child, Knox, in August of 2014. 2004 outdoor North Central Conference in 1962, McCahren served in USD’s Monday, Aug. -

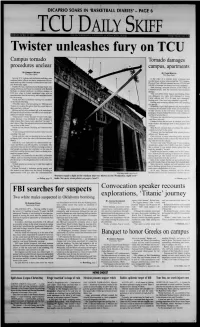

Twister Unleashes Fury on TCU Campus Tornado Tornado Damages Procedures Unclear Campus, Apartments

DICAPRIO SOARS IN 'BASKETBALL DIARIES' - PAGE 6 TCU DAILY SKIFF FRIDAY, APRIL 21,1995 TEXAS CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY, FORT WORTH. TEXAS 92NDYEAR, NO.105 Twister unleashes fury on TCU Campus tornado Tornado damages procedures unclear campus, apartments BY KIMBERLY WILSON BY CHRIS NEWTON TCU DAILY SKIFF TCU DAILY SKIFF Several TCU students and professors said they were In the wake of a tornado some witnesses said confused about official university instructions for tor- touched down several times around the TCU campus. nado warnings after a tornado touched down near cam- Physical Plant officials estimate between S25.000 and pus Wednesday night. S40.000 of damage was done to university property. Heather Novak, a sophomore psychology major, was Andy Kesling, associate director of the Office of taking American and Texas Government with Richard Communications, said the university had extensive Millsap, an adjunct professor in political science, at damage. 8:30 p.m. when a student interrupted class with an "The roof of the Miller Speech and Hearing Clinic announcement that the university had cancelled classes was damaged, two lights were damaged at Amon for the evening. Carter stadium and 15 to 20 trees were damaged." Novak said the civil defense warning was inaudible Kesling said. "One (tree) was completely uprooted." in the Moudy Building. Kesling said university officials were still assessing "We didn't know what was going on," Millsap said. the damage. "I gave my students the option that they could leave or Wednesday night. Skiff reporters and photographers they could stay with me." witnessed the aftermath of the storm and reported that Millsap said all of his students left, so he went home. -

PBATS NEWSLETTER the Annual Publication of the PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL ATHLETIC TRAINERS SOCIETY

PROUDLY PRESENTS EST 1983 Spring 2019 // Vol. 32 The NEWSLETTER Spring 2019 // Vol. 32 PBATS NEWSLETTER The Annual Publication of the PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL ATHLETIC TRAINERS SOCIETY IN THE SPOTLIGHT: ROGER CAPLINGER Not All Cancer Wears Pink By: Magie Lacambra, M.Ed., ATC hey say that life only gives you as much as you can handle. Well, Roger Caplinger was T given the biggest challenge of his life, and he rose to the occasion. A Denver, Colorado native, Roger always knew he wanted to be an athletic trainer. Following his freshman year, when football was dropped at Southern Colorado State as a result of Title IX equity, Roger transferred to Metropolitan State University to complete his bachelor’s degree (1989). This same (From left): Brett, Kyle, Roger and Jackie at the 2018 Purple Stride Walk year, Roger secured a position as an intern for the Denver Zephyrs, the Triple A affiliate of the getting burned out with the schedule and wanted Milwaukee Brewers, which eventually turned into to spend more time at home with his family. Roger positions with the club’s Rookie Ball team and pitched a new position, director of medical Pioneer League team. In 1992, Roger took a year off operations, to Doug Melvin, senior advisor baseball from baseball to earn a master’s degree from the operations, and Gord Ash, vice president Baseball University of Colorado in Boulder, before returning Projects, at the Brewers. He explained how he would to the Brewers organization as the athletic trainer ensure continuity of care by overseeing psychology, for the club’s Arizona Rookie League team. -

Rene Tosoni with One Swing of the Bat

PlayPlay BallBall!! BC Baseball Issue 8 ‘10 Rene Tosoni With One Swing of the Bat..... Play Ball! Line Up... 5 Building Better Athletes.....Jake Elder 7 He’s No Dummy.....Katie Ruskey 11 Girls Baseball in British Columbia 14 Women’s Baseball Taking Strides into the Future 17 North Langley Bombers Represent Canada at the Babe Ruth World Series 18 Around the Horn: A Baseball BC 2010 Update 19 My Father and His Passion for Sports: Ken Roulston 21 Douglas College Offers ‘New’ Coaching Degree 22 Sliding Home: When Posting Your Face Are you Closing the Book on Your Future? 23 An Umpire’s Umpire: Fabian Poulin 24 Rene Tosoni: With One Swing of the Bat 26 2010 Oldtimers Canadian Nationals Come to British Columbia 27 Marty Lehn 30 Metal versus Wood? 34 BCPBL: Clyde Inouye • Past, Present and Future 37 Pemberton Grizzlies Baseball: Grassroots Baseball Proposed BC Baseball Legacy Facility: Penticton, BC 41 Playing with Perthes 43 The 2009 World Baseball Challenge: An Inaugural Success 45 T’Birds Baseball 2010: Numbers and Young Talent Create Depth Play Ball!® BC Baseball www.playballbc.com Email: [email protected] Phone: 250 • 493 • 0363 Front Cover Photo courtesy Bruce Kluckhohn All rights reserved Copyright, 2008. All rights reserved by Play Ball!® BC Baseball. Reprint of any portion of this publication without express written permission from the Publisher, Editor, Authours, Advertisers, Photo contributors, etc is prohibited. Play Ball!® welcomes unsolicited article submissions for editorial consideration. The Editor retains the exclusive right to decline submissions and/or edit content for length and suitability. Opinions expressed in articles, does not necessarily reflect the opinions of Play Ball!® or its members. -

Mascots Midwest Through 2032, Thanks to an Agreement Their Costumed Identities Suggest Other- and Chalk Line

Hannibal Courier-Post • www.hannibal.net • FRIDAY, JULY 31, 2015 A7 (SPORTS) SPORTS SHORTS LOCAL FACES Cardinals, Fox Sports Midwest ink new deal The men behind the masks The St. Louis Cardinals will stay on Fox Sports Hannibal High School graduates break out as Hannibal Cavemen mascots Midwest through 2032, thanks to an agreement Their costumed identities suggest other- and chalk line. On Tuesday, Yochum lived up announced Thursday. wise. to the Shoeless name as he loss his left shoe in The 15-year deal begins Yochum, 19, and Kempker, 18, both life- an unplanned gag. He quickly rose to his feet in 2018 and runs through long Hannibal residents and Hannibal High and held his empty shoe in the air, pointing the 2032 season. Financial School graduates, are nearing the end of their at it angrily as if to condemn it for causing his terms of the deal were not summer as the Hannibal Cavemen baseball defeat in the race. disclosed. team’s Shoeless Joe and Rascal mascots. The hordes of children running with him The Cardinals are a And the two young men insist the char- got a kick out of it, and fans in attendance lynchpin of Fox Sports acters have brought out their personalities. laughed along with them. It was an impro- Midwest, which broad- “I feel like it’s made for us,” Yochum said vised stunt, but the type Yochum and Kemp- casts games to parts of 10 about his and his best friend’s jobs. “It’s not ker said really brings them joy in what they do. -

With the Death of Ted Rogers, Owner of Rogers Communications and the Jays, Beeston (Welland, Ont.) May Be Around a Long Enough to Shed His Interim Tag

1. Paul Beeston , CEO on an interim basis, Blue Jays (10). With the death of Ted Rogers, owner of Rogers Communications and the Jays, Beeston (Welland, Ont.) may be around a long enough to shed his interim tag. Whether he goes or stays, people will be say five years from now what a good/bad hire the next president of the Jays was. 2. Greg Hamilton , director of national teams, junior coach, Baseball Canada (1A). No ones makes as many decisions and runs through as many mine fields as he does. This year. for example. he put together four distinct rosters: The pre-Olympic tourney in March at Taiwan; the Canadian junior team, which lost in the quarters at Edmonton in August; the Olympic team in Bejing and the 2009 junior team which headed to Florida in October. He has been negotiating with MLB teams for the World Baseball Classic, to be played at the Rogers Centre in March. You can find Hamilton (Peterborough, Ont.) at his Ottawa office until 10:30 most nights. 3. Pat Gillick, senior adviser, Philadelphia Phillies (5). As GM, he guided the Phillies to the 2008 World Series — his third. He became a Canadian citizen in November of 2005 after living in Toronto since 1976 and has always supported Canadian baseball. He led the Jays, Orioles, Mariners and the Phillies to post-season play 11 times in his final 20 seasons. He added Jamie Moyer, Brad Lidge, J.C. Romero, Joe Blanton, Matt Stairs, Jayson Werth, Greg Dobbs, Scott Eyre, J.C. Romero and Chad Durbin , who were all small pieces to complete the puzzle. -

Minnesota Twins Daily Clips Sunday, July 24, 2016 Five

Minnesota Twins Daily Clips Sunday, July 24, 2016 Five-run seventh sends Twins to wild victory over Red Sox. Star Tribune (Neal lll) p. 1 Twins interim GM Antony working the phones. Star Tribune (Neal III) p. 2 Reusse: Carew bringing lots of heart to Hall of Fame this weekend. Star Tribune (Reusse) p. 3 Souhan: Being a hometown guy not an asset for interim GM Antony. Star Tribune (Souhan) p. 4 Minnesota Twins: Miguel Sano promises to fix pop-up problem. Pioneer Press (Berardino) p. 5 Twins’ Brandon Kintzler, right where he wants to be, saves win over Red Sox. Pioneer Press (Berardino) p. 7 Brandon Kintzler, Minnesota Twins hold off Boston Red Sox 2-1. Pioneer Press (Berardino) p. 8 Five-run 7th sparks Twins past Sox in wild one. MLB.com (Browne & Bollinger) p. 9 Suzuki has chin stitched up after foul tip. MLB.com (Bollinger) p. 11 This time, Twins' offense picks up pitchers. MLB.com (Bollinger) p. 11 Kintzler suddenly garnering plenty of interest. MLB.com (Bollinger) p. 12 Five-run seventh sends Twins to wild victory over Red Sox La Velle E. Neal lll | Star Tribune | July 24, 2016 BOSTON – As Twins manager Paul Molitor spoke in his office Saturday night, his players continued to yell excitedly in the clubhouse. The Twins’ 11-9 victory over the Red Sox took a little bit of everything. They blew a lead and botched some plays, but they had short memories. They got some breaks and made some breaks. They used clutching hitting, added on runs and outlasted a Boston team playing in one of the most intimidating venues in sports. -

2007 Arizona Fall League

2007 Arizona Fall League Q: What is the Arizona Fall League (AFL)? A: Major League Baseball created the Arizona Fall League in 1992 to serve as an off- season “graduate school” for top prospects. The AFL often is known as a showcase league because its players have the opportunity to display their skills for baseball scouts, general managers, and farm directors. For baseball fans, it’s a 40-day Valley homestand featuring many of baseball’s elite prospects. The Future Of Major League Q: What is the genesis of the Arizona Fall League? A: Long-time baseball executive, current special assistant to the president of the Arizona Baseball Now Diamondbacks, and Phoenix resident Roland Hemond is considered the “Architect of the Fall League.” His dream to create a six-week off-season league for baseball’s top Facts prospects in Arizona each fall became reality when the Arizona Fall League began • 2007 Fall League play in 1992 after two years of selling the concept to baseball’s hierarchy — first Hall of Fame Inductees Jermaine Dye general managers, then owners. After veteran baseball front-office executive Mike Torii Hunter Port shepherded the Fall League through its maiden voyage in 1992, former Cincinnati Derrek Lee Reds’ traveling secretary and Triple-A Columbus Clippers’ executive Steve Cobb was Ken Macha hired as the Fall League’s executive director. • Nearly 1,500 former Fall Leaguers have reached the Q: Who oversees the Arizona Fall League? major leagues A: Major League Baseball owns and operates the Arizona Fall League. Steve Cobb has • 407 Ex-AFLers On ’07 MLB been the executive director since 1993. -

Shaking up the Line-Up: Generating Principles for an Electrifying Economic Structure for Major League Baseball Jason B

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 12 Article 6 Issue 2 Spring Shaking Up the Line-Up: Generating Principles for an Electrifying Economic Structure for Major League Baseball Jason B. Myers Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw Part of the Entertainment and Sports Law Commons Repository Citation Jason B. Myers, Shaking Up the Line-Up: Generating Principles for an Electrifying Economic Structure for Major League Baseball, 12 Marq. Sports L. Rev. 631 (2002) Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol12/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHAKING UP THE LINE-UP: GENERATING PRINCIPLES FOR AN ELECTRIFYING ECONOMIC STRUCTURE FOR MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL JASON B. MYERS* I. LEADING OFF: THE GAME OF BASEBALL AND THE BUSINESS OF BASEBALL .......................................................................................... 632 A. Welcome to Today's Game .......................................................... 632 B. Baseball'sAntitrust Exemption ................................................... 635 II. BATTING SECOND: THE PERCEIVED PROBLEM, THE PROFFERED SOLUTIONS, AND THEIR SHORTCOMINGS ........................................... 640 A. The PerceivedProblem: Economics Drives Competition ........... 640 B. Proffered Solutions...................................................................... 645 1. Baseball's Blue Ribbon Panel .............................................. -

2019 Brewers Season Review Another Memorable September Leads to Back-To-Back Playoff Appearances

December 2019 Volume 13 Issue 3 Milwaukee Brewers Baseball Club Alumni Newsletter 2019 Brewers Season Review Another memorable September leads to back-to-back playoff appearances Though it wasn’t a carbon-copy run to the pennant like they engineered in 2018, the Brewers still put themselves in position to make September as memorable as the previous one when they captured the National League Central Division crown and came within one victory of returning to the World Series. Milwaukee posted its second straight 20-7 September to finish the year 89-73. It claimed its second straight postseason invitation, this time as the second Wild Card team, marking the second time in franchise history it had qualified for the playoffs. “This group fed off each other. It was a unit that believed in its abilities,” Brewers President of Baseball Operations and General Manager David Stearns said following the season. “I’m incredibly proud of the effort our team put forth this season, and further proud of the support from the entire organization to get us back to the playoffs.” “We know how challenging it is to make the playoffs in this league and to do it in back-to-back seasons for only the second time in franchise history is incredible. It’s not something we take for granted. It’s special each and every time you do it,” Stearns added. In late August, the Brewers clawed their way into contention when they were only two games above .500 by opening the final month on a 14-3 run that included winning eight games from their division rivals, the Chicago Cubs and the St. -

Career Highlights & Milestones

CAREER HIGHLIGHTS & MILESTONES Hits, Hits, Hits MLB All-Time Hits List 1. Pete Rose .............. 4,256 Most Hits in Franchise History 2. Ty Cobb ............... 4,191 3. Hank Aaron ............ 3,771 1. DEREK JETER ........ 3,443 4. Stan Musial ............ 3,630 2. Lou Gehrig ............ 2,721 5. Tris Speaker ............ 3,514 3. Babe Ruth ............. 2,518 6. DEREK JETER ........ 3,443 4. Mickey Mantle ......... 2,415 7. Honus Wagner ......... 3,430 5. Bernie Williams ........ 2,336 8. Carl Yastrzemski ....... 3,419 9. Paul Molitor ........... 3,319 10. Eddie Collins .......... 3,313 QUICK HITS • Jeter has reached the 200-hit plateau in eight different seasons in his career, tying Lou Gehrig’s club record and marking the most 200H seasons ever by a shortstop in Baseball history. • According to Elias, Jeter joins Hank Aaron as the only players to record at least 150H in 17 straight seasons, accomplishing the feat from 1996-2012. Aaron did so from 1955-71. • There are two players in Baseball history with at least 3,000H, 250HR, 300SB and 1,200RBI in their careers—Willie Mays and Derek Jeter. The Captain tips his cap to the crowd at Yankee No player in Major League history has Stadium on 9/11/09 after singling off Orioles more hits from the shortstop position starter Chris Tillman for his 2,722nd career hit, than Derek Jeter. surpassing Lou Gehrig (2,721) for the Yankees franchise record. MILESTONE HITS Hit No. Date/Opp./Type 1 ...........................................5/30/95 at Seattle (Tim Belcher), single 100. 7/17/96 at Boston (Joe Hudson), single 1,000 .................................... -

Induction Ceremony Saturday, June 13, 2015

2015 $3.00 INDUCTION CEREMONY Saturday, June 13, 2015 2015 Inductees Carlos Delgado Matt Stairs Corey Koskie Felipe Alou Bob Elliott 386 Church St. S., St. Marys, 519-284-1838 www.baseballhalloffame.ca [email protected] Whether Whether you you are are looking looking forfor aa casualcasual business business lunch, lunch, an an intimateintimate dinner dinner for for two, two, aa familyfamily celebration,celebration, or aor glass a glass of of wine wineat the at endthe end of ofthe the day, day, wewe would love love to towelcome welcome you atyou at Wildstone Bar & Grill and treat you to a comfortable, Wildstonerelaxing Bar experience & Grill with and unparalleled treat you toservice. a comfortable, relaxing experience with unparalleled service. Reservations recommended Reservations recommended940 Queen Street East St. Marys 519-284-4140 or 1-800-409-3366 [email protected] Queen Street East St. Marys 519- 284-4140 or 1-800-409-3366 [email protected] Follow us on Follow us on Table of Contents The Canadian Baseball Jackson’s Pharmacy and Stone Willow Inn wish to welcome HALL OF FAME AND MUSEUM Message from Town of St. Marys Mayor Al Strathdee 2 MailingLE MUSÉE ET address TEMPLE DE (Office): LA RENOMMÉE DU BASEBALL CANADIEN the Inductees’ families and congratulate all of this year’s inductees 2015 Inductees 5 CBHFM Carlos Delgado 6 P.O. Box 1838 140 Queen St. E. Matt Stairs 8 St. Marys, ON N4X 1C2 Corey Koskie 10 Felipe Alou 12 Museum address: Bob Elliott 14 386 Church St. S. Jack Graney Award Winners 19 St. Marys, ON N4X 1C2 In Memory of Jim Fanning 21 Phone: (519) 284-1838 Map of St.