Communication to Special Representative on the Situation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barnala Assembly Punjab Factbook

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781-84 Email : [email protected] Website : www.indiastatelections.com Online Book Store : www.indiastatpublications.com Report No. : AFB/PB-103-0121 ISBN : 978-93-5301-492-6 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : January, 2021 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 158 for the use of this publication. Printed in India Contents No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency - (Vidhan Sabha) at a Glance | Features of Assembly 1-2 as per Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency - (Vidhan Sabha) in 2 District | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary 3-10 Constituency - (Lok Sabha) | Town & Village-wise Winner Parties- 2019, 2017, 2014, 2012 and 2009 Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 11-13 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographic 4 Population Households | Rural/Urban Population | Towns and -

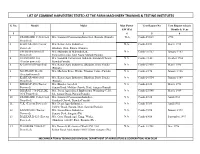

List of Combine Harvester Updated in July 2016

LIST OF COMBINE HARVESTERS TESTED AT THE FARM MACHINERY TRAINING & TESTING INSTITUTES S. No. Model Make Max Power Test Report No Test Report release kW (Ps) Month & Year 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 STANDARD C-514 (Self M/s. Standard Corporation India Ltd., Barnala (Punjab) N.A. Comb-29/615 1992 Propelled) 2 KARTAR-350 (Tractor M/s. Kartar Agro Industries, N.A. Comb-2/151 March 1975 Powered) Bhadson, Distt. Patiala (Punjab) 3 SWARAJ-8100 (Self M/s. Mahindra & Mahindra Ltd., N.A. Comb-18/357 January 1983 Propelled) Swaraj Diviision, SAS Nagar,Mohali(Punjab) 4 STANDARD 365 M/s. Standard Corporation IndiaLtd.,Standard Chowk, N.A. Comb-1/140 October 1984 (Tractor powered) Barnala(Punjab) 5 K-3500 (Self Propelled) M/s. Kartar Agro Industries, Bhadson, Distt. Patiala N.A. Comb-21/438 March 1985 (Punjab) 6 MATHARU M-350 M/s. Matharu Engg. Works, Firozpur Cantt. (Punjab) N.A. Comb-3/174 January 1986 (TractorPowered) 7 KARTAR-4000 (Self M/s. Kartar Agro Industries, Bhadson, Distt. Patiala N.A. Comb-24/534 January 1989 Propelled) (Punjab) 8 BHODAY 470 (Tractor M/s. Bhodey Agro Ltd N.A. Comb-4/350 March 1991 Powered) Sunam Road, Mehlan Chowk, Distt. Sangrur(Punjab) 9 BHARAT 730 DELUXE M/s. Jiwan Agricultural Implements Workshop C.I.S. N.A. Comb-25/540 March 1989 (Self Propelled) ltd., Sanaur Road, Patiala(Punjab) 10 STANDARD C-412 (Self M/s. Standard Corporation IndiaLtd., N.A. Comb-6/386 April 1992 Propelled) Standard Chowk, Barnala(Punjab) 11 V.K. (Tractor Powered) M/s. -

Contact Detail of Blos to Be Provided by Eros District No

Contact Detail of BLOs to be provided by EROs District No. & Name: Department/ AC No. Part No. Name Designation Mobile No Organisation 103-Barnala 1 Amrik Singh ETT TEACHER GPS Bhadalwad 98152-38466 GHS 103-Barnala 2 Sukhwinder Singh ETT TEACHER 80545-00510 BHADALWAD GHS 103-Barnala 3 Vikas Goyal DPE TEACHER 94171-24090 BHADALWAD 103-Barnala 4 MegRaj SLA GSSS HAMIDI 98768-21820 GPS 103-Barnala 5 Rana Singh ETT TEACHER 98721-20907 KARAMGARH AGRICULTURE 103-Barnala 6 Karminder Singh A/R 99140-07490 KARAMGARH COMPUTER G.H SCHOOL 103-Barnala 7 Gurmit Singh 98156-91500 TEACHER KARAMGARH 103-Barnala 8 Jaskaran Singh CLERK GPS THULEWAL 80541-28938 103-Barnala 9 Baldev Singh ETT TEACHER GPS NANGAL 88727-99638 103-Barnala 10 Ramandeep Singh ETT TEACHER GPS THELIWAL 99146-23001 103-Barnala 11 Gurgeet Singh ETT TEACHER GPS THELEWAL 94174-52488 103-Barnala 12 Jagseer Singh ETT TEACHER GPS JHALUR 97801-94294 103-Barnala 13 Sukhpal Singh ETT TEACHER GPS JHALUR 99156-53156 103-Barnala 14 Dilpreet Singh ART & CRAFT GSSS JHALOOR 98143-80049 103-Barnala 15 Pargat Singh ETT TEACHER GPS KATTU 98880-28683 MARKET 103-Barnala 16 Gulzar Singh GA 98761-46343 COMMITTEE 103-Barnala 17 Ranjit Singh ETT TEACHER GPS SEKHA 97810-22384 103-Barnala 18 Baljeet Singh ETT TEACHER GPS SANGHERA 86997-40100 103-Barnala 19 Amarjit Singh PTI GSS SEKHA 98031-52942 GPS SANDHU 103-Barnala 20 Jagrant Singh ETT TEACHER 95010-17066 PATTI HS SCHOOL 103-Barnala 21 Mandeep Sharma CLERK 95012-93700 KARAMGARH BURAJ 103-Barnala 22 Chamkaur Singh ETT TEACHER 95010-19060 FATEHGARH 103-Barnala -

(OH) Category 1 59 Jaswinder Singh S/O S.B.S Nagar, Barnala, 09.01.1989 OH 40% Jagjit Singh Distt: Barnala

Department of Local Government Punjab (Punjab Municipal Bhawan, Plot No.-3, Sector-35 A, Chandigarh) Detail of application for the posts of Safai Karamchari (Service Group-D) reserved for Disabled Persons in the cadre of Municipal Corporations and Municipal Councils-Nagar Panchayats in Punjab Sr. App Name of Candidate Address Date of Birth VH, HH, OH No. No. and Father’s Name etc. %age of Sarv Shri/ Smt./Miss Disability 1 2 3 4 5 6 Orthopedically Handicapped (OH) Category 1 59 Jaswinder Singh S/o S.B.S Nagar, Barnala, 09.01.1989 OH 40% Jagjit Singh Distt: Barnala. 2 80 Jagjeet Singh S/o Vill. Phalla Patti, VPO. 30.12.1987 OH 40% Gurjant Singh Bhathlan, Teh.& Distt. Barnala 3 93 Gagandeep Singh S/o Mann Patti Sekha, 01.11.1988 OH 70% Ranjeet Singh Barnala, Distt: Barnala. 4 100 Gurtej Singh S/o Navi Basti, Dhanaula, 11.07.1993 OH 32% Chajju Singh Distt. Barnala Disability less then 40% 5 136 Gurpreet Singh S/o Village-Kothe Bhan 07.08.1989 OH 60% Ginder Singh Singh, Teh.-Bhadaur, Distt- Barnala 6 174 Rajinder Singh S/o H.N.-B-XI/2488, S.No 1, 14.04.1986 OH 90% Dharmpal Singh Guru Nanak Nagar Barnala, Teh. & Distt.- Barnala 7 179 Joti D/o Manjeet H.No B1X/268, Guru 02.04.1992 Disability Singh Nanak Pura Muhalla certificate not Barnala , Distt.-Barnala attached 8 185 Mithan Lal S/o H.No 277, Near Nam 15.05.1990 OH 40% Gurdial Singh Dev Gurdwara Tappa, Distt.-Barnala 9 200 Gurpreet Singh S/o H.No 2355, W.No 23 19.03.1996 OH 60% Avtar Singh ,YS School Galli, Distt. -

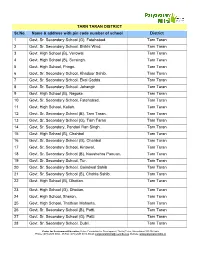

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & Address With

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & address with pin code number of school District 1 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 2 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Bhikhi Wind. Tarn Taran 3 Govt. High School (B), Verowal. Tarn Taran 4 Govt. High School (B), Sursingh. Tarn Taran 5 Govt. High School, Pringri. Tarn Taran 6 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Khadoor Sahib. Tarn Taran 7 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Ekal Gadda. Tarn Taran 8 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Jahangir Tarn Taran 9 Govt. High School (B), Nagoke. Tarn Taran 10 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 11 Govt. High School, Kallah. Tarn Taran 12 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Tarn Taran. Tarn Taran 13 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Tarn Taran Tarn Taran 14 Govt. Sr. Secondary, Pandori Ran Singh. Tarn Taran 15 Govt. High School (B), Chahbal Tarn Taran 16 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Chahbal Tarn Taran 17 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Kirtowal. Tarn Taran 18 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Naushehra Panuan. Tarn Taran 19 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Tur. Tarn Taran 20 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Goindwal Sahib Tarn Taran 21 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Chohla Sahib. Tarn Taran 22 Govt. High School (B), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 23 Govt. High School (G), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 24 Govt. High School, Sheron. Tarn Taran 25 Govt. High School, Thathian Mahanta. Tarn Taran 26 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Patti. Tarn Taran 27 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Patti. Tarn Taran 28 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Dubli. Tarn Taran Centre for Environment Education, Nehru Foundation for Development, Thaltej Tekra, Ahmedabad 380 054 India Phone: (079) 2685 8002 - 05 Fax: (079) 2685 8010, Email: [email protected], Website: www.paryavaranmitra.in 29 Govt. -

(OH) Category 1 203 Baljinder Singh S/O Village Sooch Patti 14.07.1999 OH 50% Gursewek Singh W.No.10, Handiaya, Distt

Department of Local Government Punjab (Punjab Municipal Bhawan, Plot No.-3, Sector-35 A, Chandigarh) Detail of application for the posts of Beldar, Mali, Mali-cum-Chowkidar, Mali -cum-Beldar- cum-Chowkidar and Road Gang Beldar reserved for Disabled Persons in the cadre ofMunicipal Corporations and Municipal Councils-Nagar Panchayats in Punjab Sr. App Name of Candidate Address Date of Birth VH, HH, OH No. No. and Father’s Name etc. %age of Sarv Shri/ Smt./ Miss disability 1 2 3 4 5 6 Orthopedically Handicapped (OH) Category 1 203 Baljinder Singh S/o Village Sooch Patti 14.07.1999 OH 50% Gursewek Singh W.No.10, Handiaya, Distt. Barnala, Punjab. 2 311 Jagseer Singh S/o VPO Thikriwala, Dhillon 01.07.1973 OH 60% Gurmail Singh Patti, Teh.& Distt. Barnala, Punjab. 3 312 Surinder Singh S/o VPO Khudi Kalan, Teh. & 03.04.1983 OH 50% Sudagar Singh Distt. Barnala, Punjab. 4 316 Inderjeet Singh S/o VPO Ugoke, Teh. Tappa, 27.12.1993 OH 80% Niranjan Singh Distt. Barnala, Punjab. 5 317 Keshav Rai S/o Sita Model Town, Ward No. 8, 20.07.1990 OH 70% Ram Tappa, Distt. Barnala, Punjab. 6 321 Rinka Singh S/o Nahar VPO Harigarh, Distt. 06.08.1992 OH 65% Singh Barnala, Punjab. 7 354 Sukhpal Singh S/o Vill. Bhaini Fatta, Teh. 05.01.1974 OH 60% Darbara Singh Tappa, Distt. Barnala, Punjab. 8 370 Harpreet Singh S/o VPO Bhattlan, Teh. & 02.06.1995 OH 65% Sukhwinder Singh Distt. Barnala, Punjab. 9 492 Kuldeep Singh S/o Vill. Dhilwan, Mohalla 02.09.1993 OH 60% Baldev Singh Patti, Teh. -

Find Police Station

Sr.No. NAME OF THE POLICE E.MAIL I.D. OFFICIAL PHONE NO. STATION >> AMRITSAR – CITY 1. PS Div. A [email protected] 97811-30201 2. PS Div. B [email protected] 97811-30202 3. PS Div. C [email protected] 97811-30203 4. PS Div. D [email protected] 97811-30204 5. PS Div. E [email protected] 97811-30205 6. PS Civil Lines [email protected] 97811-30208 7. PS Sadar [email protected] 97811-30209 8. PS Islamabad [email protected] 97811-30210 9. PS Chheharta [email protected] 97811-30211 10. PS Sultanwind [email protected] 97811-30206 11. PS Gate Hakiman [email protected] 97811-30226 12. PS Cantonment [email protected] 97811-30237 13. PS Maqboolpura [email protected] 97811-30218 14. PS Women [email protected] 97811-30320 15. PS NRI [email protected] 99888-26066 16. PS Airport [email protected] 97811-30221 17. PS Verka [email protected] 9781130217 18. PS Majitha Road [email protected] 9781130241 19. PS Mohkampura [email protected] 9781230216 20. PS Ranjit Avenue [email protected] 9781130236 PS State Spl. -

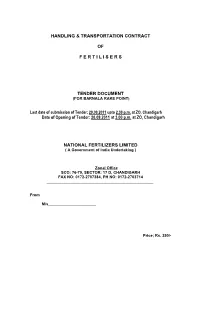

Handling & Transportation Contract

HANDLING & TRANSPORTATION CONTRACT OF F E R T I L I S E R S TENDER DOCUMENT (FOR BARNALA RAKE POINT) Last date of submission of Tender: 20.09.2011 upto 2.30 p.m. at ZO, Chandigarh Date of Opening of Tender: 20.09.2011 at 3.00 p.m. at ZO, Chandigarh NATIONAL FERTILIZERS LIMITED ( A Government of India Undertaking ) Zonal Office SCO: 76-79, SECTOR: 17 D, CHANDIGARH FAX NO: 0172-2707384, PH NO: 0172-2703714 _________________________________________________ From M/s______________________ ____________________________ ____________________________ Price; Rs. 250/- NATIONAL FERTILIZERS LIMITED INSTRUCTIONS TO THE TENDERER National Fertilizers Limited is the second largest producer and marketer of nitrogenous fertilisers in the country. The five-urea production units of the company are located one each at Nangal and Bathinda in Punjab, Panipat in Haryana and two at Vijaipur in Madhya Pradesh. To make the urea available to the farmers through a network of dealers, Co-operatives, Agro industries Corporation etc., Urea is dispatched through rakes from the production units up- to rake points in different states. At these rake-points, services of handling and transport contractors are required to clear the rakes and to further transport the material to the sale / storage points. Parties who are pre-qualified through a separate process are to submit this tender and thereafter the contracts are finalized. Parties should go through the contents of this tender document carefully and submit it along with all the required documents / information. The cost of the Tender document is Rs. 250/- (Rupees two hundred and fifty only). Tender document may be purchased from the Area Office / Zonal Office concerned by payment through Demand Draft drawn in favour of National Fertilizers Limited and payable at the place of location of Area / Zonal Office. -

New Dev Initiatives 31-01-2007 Annex 1.2 - Contract Farming 1 Rs Lacs ITEM 1.6 a : MACRO MANAGEMENT WORK PLAN - AGRICULTURE 2005-06 As on 31/1/07

ITEM 1.2 : CONTRACT FARMING As on 31/1/07 SN Crop 2005-06 2006-07 Kharif 2005 Rabi 2005-06 Kharif 2006 Rabi 2006-07 (Target) (Achievement) Acres Acres Acres Acres 1 Hyola/Gobhi Sarson 68382 105500 2 Sunflower 17942 75000 3 Malting Barley 4566 15000 4 Winter Maize 5 Spring Maize 6386 15000 6 Durum Wheat 2000 4000 7 Moong 1446 2400 - 2500 8 Basmati 42259 35000 9 Maize 57,704 75000 10 Guar 1136 1030 11 Castor 12 Mentha 4673 13 Potato/Seed 7289 Total 102545 113638 111030 217000 Grand Total 216183 328030 Annexures - New Dev Initiatives 31-01-2007 Annex 1.2 - Contract Farming 1 Rs lacs ITEM 1.6 A : MACRO MANAGEMENT WORK PLAN - AGRICULTURE 2005-06 As on 31/1/07 SN Component Physical Outlay Released by Released by State Govt. Expenditure Remarks Target Achievement GOIS SSGOI GOIS SS (h) II Machinery for demonstration such as - - 5.40 0.60 5.40 5.40 0.60 laser based leveler etc. (i) Demonstration Charges - - 2.70 0.30 2.70 2.70 0.30 4 RECLAMATION OF ALKALI SOILS (a) Area to be Reclaimed (Hect.) 6500 5986 90.00 10.00 90.00 87.56 5 DEVELOPMENT OF BEE-KEEPING FOR IMPROVING CROP PRODUCTIVITY (a) Subsidy on bee-colonies @ 25% or Rs. 250/- 3000 - 6.75 0.75 6.75 6.75 0.75 per colony which ever is less. (b) Subsidy on Distribution of hive/equipment @ 2715 - 8.55 0.95 8.55 8.55 0.95 - 25% or Rs. 350/- per hive/equipment which ever is less. -

Presentation Under Housing for All

Govt. of Punjab Department of Local Government Presentation under Housing for all DATE:-29/8/2019 PROGRESS OF PROJECTS Verticals Houses Work Grounded/In Progress Completed Approved order Issued Foundatio Lintel Roof Total n Casted ISSR - - - - - - - - AHP 570 570 - - - - BLC (N/E) 45,429 23,599 1,769 1,579 3,171 - 2,831 CLSS Till 28.08.2019, upfront subsidy of Rs 217.81 Cr. released to 9,915 beneficiaries. Note: Provide the details of relevant projects 2 MIS-PORTAL STATUS(BLC) • As per MIS-Portal no. of projects approved are 545 out of which 544 uploaded on MIS. • Percentage of projects uploaded is 99.81% • No. of approved beneficiaries are 45423out of which 38742 are attached. GEO-TAGGING STATUS Geo-tagging status of Punjab as per MIS- portal is 15661. It was found that certain houses in State of Punjab were not Geo- tagged accurately. Hence, the consultants were asked to reconsider the Geo-tagging process. Consultants have again begin the process of Geo-tagging. BLC DPR PROPOSALS – 126 Towns (126 DPRs) PROJECT PROPOSAL BRIEF Sr. No, Details Amount 1 No. of Projects 126 2 No. of Cities 126 3 No. of DUs 10234 4 Project Cost (Rs. in Lakhs) 31500.00 5 Central Share (Rs. in Lakhs) 15351.00 6 State Share (Rs. in Lakhs) 2559 7 Beneficiary Share (Rs. in Lakhs) 13590 Proposal for DPR under Vertical IV - BLC Project Cost in Lakhs Name of City / No of 1st Installment Sr. No. Total Project Central Beneficiary Town/District Beneficiaries State Share of Central Cost Assistance Share Assistance 1 Doraha 10 30.780 15 2.5 13.28 6 2 Chamkaur Sahib 116 -

Market Committees & Length of Link Roads Under the Jurisdiction Of

Market Committees & Length of Link Roads Under the Jurisdiction of PWD,B&R updated up to 31.03.2019 Sr.N District Nos of MC Market Committee Converted o Length (10'wide) in km 1 2 3 4 5 1 Amritsar 1 Majitha 396.03 2 Amritsar 2 Mehta 361.16 3 Amritsar 3 Rayya 457.11 Amritsar Total 1214.30 4 Barnala 1 Barnala 357.35 5 Barnala 2 Dhanaula 251.01 6 Barnala 3 Tapa 271.71 Barnala Total 880.07 7 Bathinda 1 Bathinda 322.80 8 Bathinda 2 Bhagta 330.80 9 Bathinda 3 Bhucho 317.86 10 Bathinda 4 Goniana 262.40 11 Bathinda 5 Maur 278.56 12 Bathinda 6 Raman 274.75 13 Bathinda 7 Rampura 586.18 14 Bathinda 8 Sangat 249.27 15 Bathinda 9 Talwandi Sabo 308.44 16 Bathinda 10 Nathana Bathinda Total 2931.06 17 Fazilka 1 Jallalabad 771.92 Fazilka Total 771.92 18 Ferozepur 1 Ferozepur city 494.66 19 Ferozepur 2 Guruharsahai 467.13 20 Ferozepur 3 Mallanwala 269.59 21 Ferozepur 4 Mamdot 274.39 Ferozepur Total 1505.77 22 Gurdaspur 1 Dhariwal 520.30 23 Gurdaspur 2 Gurdaspur 852.06 24 Gurdaspur 3 Kahnuwan 489.14 25 Gurdaspur 4 Kalanaur 420.07 26 Gurdaspur 5 Qadian 382.24 27 Gurdaspur 6 Shri Hargobindpur 361.26 Gurdaspur Total 3025.07 28 Hoshiarpur 1 Dasuya 503.29 29 Hoshiarpur 2 Garhshankar 1068.89 30 Hoshiarpur 3 Hoshiarpur 1539.11 31 Hoshiarpur 4 Mukerian 1005.01 Market Committees & Length of Link Roads Under the Jurisdiction of PWD,B&R updated up to 31.03.2019 Sr.N District Nos of MC Market Committee Converted o Length (10'wide) in km 1 2 3 4 5 32 Hoshiarpur 5 Tanda 382.41 Hoshiarpur Total 4498.71 33 Jalandhar 1 Adampur 328.21 34 Jalandhar 2 Bhogpur 225.13 35 Jalandhar 3 Jal City 593.32 36 Jalandhar 4 Jalandhar Cantt. -

List of 3500 VLE Cscs in Punjab

Sr No District Csc_Id Contact No Name Email ID Subdistrict_Name Village_Name Village Code Panchayat Name Urban_Rural Kiosk_Street Kiosk_Locality 1 Amritsar 247655020012 9988172458 Ranjit Singh [email protected] 2 Amritsar 479099170011 9876706068 Amot soni [email protected] Ajnala Nawan Pind (273) 37421 Nawan Pind Rural Nawanpind Nawanpind 3 Amritsar 239926050016 9779853333 jaswinderpal singh [email protected] Baba Bakala Dolonangal (33) 37710 Baba Sawan Singh Nagar Rural GALI NO 5 HARSANGAT COLONY BABA SAWAN SINGH NAGAR 4 Amritsar 677230080017 9855270383 Barinder Kumar [email protected] Amritsar -I \N 9000532 \N Urban gali number 5 vishal vihar 5 Amritsar 151102930014 9878235558 Amarjit Singh [email protected] Amritsar -I Abdal (229) 37461 Abdal Rural 6 Amritsar 765534200017 8146883319 ramesh [email protected] Amritsar -I \N 9000532 \N Urban gali no 6 Paris town batala road 7 Amritsar 468966510011 9464024861 jagdeep singh [email protected] Amritsar- II Dande (394) 37648 Dande Rural 8 Amritsar 215946480014 9569046700 gursewak singh [email protected] Baba Bakala Saido Lehal (164) 37740 Saido Lehal Rural khujala khujala 9 Amritsar 794366360017 9888945312 sahil chabbra [email protected] Amritsar -I \N 9000540 \N Urban SARAIN ROAD GOLDEN AVENUE 10 Amritsar 191162640012 9878470263 amandeep singh [email protected] Amritsar -I Athwal (313) 37444 \N Urban main bazar kot khalsa 11 Amritsar 622551690010 8437203444 sarbjit singh [email protected] Baba Bakala Butala (52) 37820 Butala Rural VPO RAJPUR BUTALA BUTALA 12 Amritsar 479021650010 9815831491 hatinder kumar [email protected] Ajnala \N 9000535 \N Urban AMRITSAR ROAD AJNALa 13 Amritsar 167816510013 9501711055 Niketan [email protected] Baba Bakala \N 9000545 \N Urban G.T.