Madonna and Child

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gold Leafs in 14Th Century Florentine Painting Feuilles D’Or Dans La Peinture Florentine Du Xive Siècle

ArcheoSciences Revue d'archéométrie 33 | 2009 Authentication and analysis of goldwork Gold leafs in 14th century Florentine painting Feuilles d’or dans la peinture florentine du XIVe siècle Giovanni Buccolieri, Alessandro Buccolieri, Susanna Bracci, Federica Carnevale, Franca Falletti, Gianfranco Palam, Roberto Cesareo and Alfredo Castellano Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/archeosciences/2532 DOI: 10.4000/archeosciences.2532 ISBN: 978-2-7535-1598-7 ISSN: 2104-3728 Publisher Presses universitaires de Rennes Printed version Date of publication: 31 December 2009 Number of pages: 409-415 ISBN: 978-2-7535-1181-1 ISSN: 1960-1360 Electronic reference Giovanni Buccolieri, Alessandro Buccolieri, Susanna Bracci, Federica Carnevale, Franca Falletti, Gianfranco Palam, Roberto Cesareo and Alfredo Castellano, « Gold leafs in 14th century Florentine painting », ArcheoSciences [Online], 33 | 2009, Online since 10 December 2012, connection on 19 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/archeosciences/2532 ; DOI : 10.4000/ archeosciences.2532 Article L.111-1 du Code de la propriété intellectuelle. Gold leafs in 14th century Florentine painting Feuilles d’or dans la peinture florentine du XIVe siècle Giovanni Buccolieri*, Alessandro Buccolieri*, Susanna Bracci**, Federica Carnevale*, Franca Falletti**, Gianfranco Palamà*, Roberto Cesareo*** and Alfredo Castellano* Abstract: Gold leafs are typically present in paintings and frescoes of the Italian Renaissance in the 13th and 14th centuries. he chemical com- position and thickness of gold leafs provide important information toward a better understanding of the technology of that epoch. he present paper discusses the results of non-destructive analysis carried out with a portable energy dispersive X-ray luorescence (ED-XRF) equipment on the 14th century panel Annunciation with Saints Catherine of Alexandria, Anthony Abbot, Proculus and Francis by the painter Lorenzo Monaco. -

Madonna and Child on a Curved Throne C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Thirteenth and Fourteenth Century Paintings Byzantine 13th Century Madonna and Child on a Curved Throne c. 1260/1280 tempera on linden panel painted surface: 82.4 x 50.1 cm (32 7/16 x 19 3/4 in.) overall: 84 x 53.5 cm (33 1/16 x 21 1/16 in.) framed: 90.8 x 58.3 x 7.6 cm (35 3/4 x 22 15/16 x 3 in.) Andrew W. Mellon Collection 1937.1.1 ENTRY The painting shows the Madonna seated frontally on an elaborate, curved, two-tier, wooden throne of circular plan.[1] She is supporting the blessing Christ child on her left arm according to the iconographic tradition of the Hodegetria.[2] Mary is wearing a red mantle over an azure dress. The child is dressed in a salmon-colored tunic and blue mantle; he holds a red scroll in his left hand, supporting it on his lap.[3] In the upper corners of the panel, at the height of the Virgin’s head, two medallions contain busts of two archangels [fig. 1] [fig. 2], with their garments surmounted by loroi and with scepters and spheres in their hands.[4] It was Bernard Berenson (1921) who recognized the common authorship of this work and Enthroned Madonna and Child and who concluded—though admitting he had no specialized knowledge of art of this cultural area—that they were probably works executed in Constantinople around 1200.[5] These conclusions retain their authority and continue to stir debate. -

2018 Bibliography

University of Dayton eCommons Marian Bibliographies Research and Resources 2018 2018 Bibliography Sebastien B. Abalodo University of Dayton, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/imri_bibliographies eCommons Citation Abalodo, Sebastien B., "2018 Bibliography" (2018). Marian Bibliographies. 17. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/imri_bibliographies/17 This Bibliography is brought to you for free and open access by the Research and Resources at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Bibliographies by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Marian Bibliography 2018 Page 1 International Marian Research Institute University of Dayton, Ohio, USA Bibliography 2018 English Anthropology Calloway, Donald H., ed. “The Virgin Mary and Theological Anthropology.” Special issue, Mater Misericordiae: An Annual Journal of Mariology 3. Stockbridge, MA: Marian Fathers of the Immaculate Conception of the B.V.M., 2018. Apparitions Caranci, Paul F. I am the Immaculate Conception: The Story of Bernadette of Lourdes. Pawtucket, RI: Stillwater River Publications, 2018. Clayton, Dorothy M. Fatima Kaleidoscope: A Play. Haymarket, AU-NSW: Little Red Apple Publishing, 2018. Klimek, Daniel Maria. Medjugorje and the Supernatural Science, Mysticism, and Extraordinary Religious Experience. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018. Maunder, Chris. Our Lady of the Nations: Apparitions of Mary in Twentieth-Century Catholic Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018. Musso, Valeria Céspedes. Marian Apparitions in Cultural Contexts: Applying Jungian Concepts to Mass Visions of the Virgin Mary. Research in Analytical Psychology and Jungian Studies. London: Routledge, 2018. Also E-book Sønnesyn, Sigbjørn. Review of William of Malmesbury: The Miracles of the Blessed Virgin Mary. -

En/Gendering Representations of Childbirth in Fifteenth-Century Franco-Flemish Devotional Manuscripts

En/Gendering Representations of Childbirth in Fifteenth-Century Franco-Flemish Devotional Manuscripts Two Volumes Elizabeth Anne L'Estrange dL V ,0 Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degreeof Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Fine Art, History of Art, and Cultural Studies September2003 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from this thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My thanks go firstly to my supervisors, Tony Hughes and Eva Frojmovic, whose encouragementand close criticisms have been very much appreciated.Their ability to seethis thesis from many different perspectives has been extremely helpful. I also thank Oliver Pickering and Adrian Wilson for their time and comments, and Ian Moxon, whose assistancewith Latin has been invaluable. I am grateful to the University of Leeds for their financial assistancein the form of a ResearchScholarship. My friends have been a constant source of emotional support during this project and thanks go in particular to Rhiannon Daniels and Eva De Visscher. I am also grateful to Phillippa Plock and Cathy McClive for our lively discussions. I am especially indebted to those friends with whom I have escaped to sunnier climes: Eleanor Wilson, Kate Bingham, Rachael Morris, and Caroline Braley. I also thank Shane Blanchard for his support and for his supply of cricketing anecdotes. Finally I thank my Mum and Dad, and my brother Rob, whose continual love and encouragementallowed me to start and finish this thesis. -

Apparitions of the Virgin Mary in Modern European Roman Catholicism

APPARITIONS OF THE VIRGIN MARY IN MODERN EUROPEAN ROMAN CATHOLICISM (FROM 1830) Volume 2: Notes and bibliographical material by Christopher John Maunder Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD The University of Leeds Department of Theology and Religious Studies AUGUST 1991 CONTENTS - VOLUME 2: Notes 375 NB: lengthy notes which give important background data for the thesis may be located as follows: (a) historical background: notes to chapter 1; (b) early histories of the most famous and well-documented shrines (La Salette, Lourdes, Pontmain, Beauraing, Banneux): notes (3/52-55); (c) details of criteria of authenticity used by the commissions of enquiry in successful cases: notes (3/71-82). Bibliography 549 Various articles in newspapers and periodicals 579 Periodicals specifically on the topic 581 Video- and audio-tapes 582 Miscellaneous pieces of source material 583 Interviews 586 Appendices: brief historical and bibliographical details of apparition events 587 -375- Notes NB - Format of bibliographical references. The reference form "Smith [1991; 100]" means page 100 of the book by Smith dated 1991 in the bibliography. However, "Smith [100]" means page 100 of Smith, op.cit., while "[100]" means ibid., page 100. The Roman numerals I, II, etc. refer to volume numbers. Books by three or more co-authors are referred to as "Smith et al" (a full list of authors can be found in the bibliography). (1/1). The first marian apparition is claimed by Zaragoza: AD 40 to St James. A more definite claim is that of Le Puy (AD 420). O'Carroll [1986; 1] notes that Gregory of Nyssa reported a marian apparition to St Gregory the Wonderworker ('Thaumaturgus') in the 3rd century, and Ashton [1988; 188] records the 4th-century marian apparition that is supposed to have led to the building of Santa Maria Maggiore basilica, Rome. -

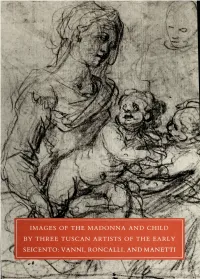

IMAGES of the MADONNA and CHILD by THREE TUSCAN ARTISTS of the EARLY SEICENTO: VANNI, RONCALLI, and MANETTI Digitized by Tine Internet Arcliive

r.^/'v/\/ f^jf ,:\J^<^^ 'Jftf IMAGES OF THE MADONNA AND CHILD BY THREE TUSCAN ARTISTS OF THE EARLY SEICENTO: VANNI, RONCALLI, AND MANETTI Digitized by tine Internet Arcliive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/innagesofmadonnacOObowd OCCASIONAL PAPERS III Images of the Madonna and Child by Three Tuscan Artists of the Early Seicento: Vanni, Roncalli, and Manetti SUSAN E. WEGNER BOWDOIN COLLEGE MUSEUM OF ART BRUNSWICK, MAINE Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number 86-070511 ISBN 0-91660(>-10-4 Copyright © 1986 by the President and Trustees of Bowdoin College All rights reserved Designed by Stephen Harvard Printed by Meriden-Stinehour Press Meriden, Connecticut, and Lunenburg, Vermont , Foreword The Occasional Papers of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art began in 1972 as the reincarnation of the Bulletin, a quarterly published between 1960 and 1963 which in- cluded articles about objects in the museum's collections. The first issue ofthe Occasional Papers was "The Walker Art Building Murals" by Richard V. West, then director of the museum. A second issue, "The Bowdoin Sculpture of St. John Nepomuk" by Zdenka Volavka, appeared in 1975. In this issue, Susan E. Wegner, assistant professor of art history at Bowdoin, discusses three drawings from the museum's permanent collection, all by seventeenth- century Tuscan artists. Her analysis of the style, history, and content of these three sheets adds enormously to our understanding of their origins and their interconnec- tions. Professor Wegner has given very generously of her time and knowledge in the research, writing, and editing of this article. Special recognition must also go to Susan L. -

Transforming Visions? Apparitions of Mary

30 Transforming visions? Apparitions of Mary Chris Maunder Introduction: apparitions of Mary in medieval England and modern EuropJ T A TIME AROUND THE BEGINNING of the eighth century, a swineherd A named Eoves or Eof experienced a vision of three women at a place that we now know as Evesham in Worcestershire, named after him. The woman in the centre was identified as the Virgin Mary, although anyone familiar with the ancient triple goddess in works by Robert Graves and others would probably suggest that this was a christianization of a pagan story. A Benedictine monk Ecgwin, bishop of Worcester, visiting the site, also had a vision of Mary there, and established the abbey which remained until the Reformation; it is now a much-visited ruin with several surviving medieval buildings. The full story of Eoves and Ecgwin is peculiar to Evesham, but the underlying structure is a familiar one in Catholicism. The typical apparition is rooted in local traditions, traditions which stand at the interface between doctrinal Christianity and common religion with its folklore and belief in the spirit world. 2 The visionary is often someone located in the liminal (marginal) region between society and nature, usually a herder of animals at the edge of the village. If the apparition is to take its place in history, however, it has to receive the approval of the church hierarchy. This process of legitimization is also one in which the story sheds much of its common religion element, and becomes instead associated with the establishment of an official religious centre. As the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci noted, the Roman Catholic Church is very effective at integrating the popular and official in religious devotion. -

And Post-Vatican Ii (1943-1986 American Mariology)

FACULTAS THEOLOGICA "MARIANUM" MARIAN LffiRARY INSTITUTE (UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON) TITLE: THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF BIBLICAL MARIOLOGY PRE- AND POST-VATICAN II (1943-1986 AMERICAN MARIOLOGY) A thesis submitted to The Theological Faculty "Marianwn" In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Licentiate of Sacred Theology By: James J. Tibbetts, SFO Director: Reverend Bertrand A. Buby, SM Thesis at: Marian Library Institute Dayton, Ohio, USA 1995 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 The Question of Development I. Introduction - Status Questionis 1 II. The Question of Historical Development 2 III. The Question of Biblical Theological Development 7 Footnotes 12 Chapter 2 Historical Development of Mariology I. Historical Perspective Pre- to Post Vatican Emphasis A. Mariological Movement - Vatican I to Vatican II 14 B. Pre-Vatican Emphasis on Scripture Scholarship 16 II. Development and Decline in Mariology 19 III. Development and Controversy: Mary as Church vs. Mediatrix A. The Mary-Church Relationship at Vatican II 31 B. Mary as Mediatrix at Vatican II 37 c. Interpretations of an Undeveloped Christology 41 Footnotes 44 Chapter 3 Development of a Biblical Mariology I. Biblical Mariology A. Development towards a Biblical Theology of Mary 57 B. Developmental Shift in Mariology 63 c. Problems of a Biblical Mariology 67 D. The Place of Mariology in the Bible 75 II. Symbolism, Scripture and Marian Theology A. The Meaning of Symbol 82 B. Marian Symbolism 86 c. Structuralism and Semeiotics 94 D. The Development of Two Schools of Thought 109 Footnotes 113 Chapter 4 Comparative Development in Mariology I. Comparative Studies - Scriptural Theology 127 A. Richard Kugelman's Commentary on the Annunciation 133 B. -

VENERABLE POPE PIUS XII and the 1954 MARIAN YEAR: a STUDY of HIS WRITINGS WITHIN the CONTEXT of the MARIAN DEVOTION and MARIOLOGY in the 1950S

INTERNATIONAL MARIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON, OHIO In affiliation with the PONTIFICAL FACULTY OF THEOLOGY "MARIANUM" The Very Rev. Canon Matthew Rocco Mauriello VENERABLE POPE PIUS XII AND THE 1954 MARIAN YEAR: A STUDY OF HIS WRITINGS WITHIN THE CONTEXT OF THE MARIAN DEVOTION AND MARIOLOGY IN THE 1950s A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Licentiate of Sacred Theology with Specialization in Mariology Director: The Rev. Thomas A. Thompson, S.M. Marian Library/International Marian Research Institute University ofDayton 300 College Park Dayton OH 45469-1390 2010 To The Blessed Virgin Mary, with filial love and deep gratitude for her maternal protection in my priesthood and studies. MATER MEA, FIDUCIA MEA! My Mother, my Confidence ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My sincerest gratitude to all who have helped me by their prayers and support during this project: To my parents, Anthony and Susan Mauriello and my family for their encouragement and support throughout my studies. To the Rev. Thomas Thompson, S.M. and the Rev. Johann Roten, S.M. of the International Marian Research Institute for their guidance. To the Rev. James Manning and the staff and people of St. Albert the Great Parish in Kettering, Ohio for their hospitality. To all the friends and parishioners who have prayed for me and in particular for perseverance in this project. iii Goal of the Research The year 1954 was very significant in the history of devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary. A Marian Year was proclaimed by Pope Pius XII by means of the 1 encyclical Fulgens Corona , dated September 8, 1953. -

The Virgin Mary: a Paradoxical Model for Roman Catholic Immigrant Women of the Nineteenth Century

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council --Online Archive National Collegiate Honors Council Spring 2007 The Virgin Mary: A Paradoxical Model for Roman Catholic Immigrant Women of the Nineteenth Century Darris Catherine Saylors University of Tennessee - Chattanooga, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nchcjournal Part of the Higher Education Administration Commons Saylors, Darris Catherine, "The Virgin Mary: A Paradoxical Model for Roman Catholic Immigrant Women of the Nineteenth Century" (2007). Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council --Online Archive. 31. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nchcjournal/31 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the National Collegiate Honors Council at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council --Online Archive by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. DARRIS CATHERINE SAYLORS The Virgin Mary: A Paradoxical Model for Roman Catholic Immigrant Women of the Nineteenth Century DARRIS CATHERINE SAYLORS 2006 NCHC PORTZ SCHOLAR UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE AT CHATTANOOGA INTRODUCTION his paper identifies and discusses several examples of Marian paradoxes Tto better understand how constructions of Mary as the primary model of feminine religiosity affected Roman Catholic immigrant women. Such para- doxes include Mary’s perpetual virginity juxtaposed with earthly women’s commitment to family (and the sexual relationship implicit in marriage) and the classist elements inherent in the True Womanhood model related to Mary. -

Madonna and Child Enthroned with Twelve

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Agnolo Gaddi Florentine, c. 1350 - 1396 Madonna and Child Enthroned with Twelve Angels, and with the Blessing Christ [middle panel] shortly before 1387 tempera on poplar panel overall: 204 × 80 cm (80 5/16 × 31 1/2 in.) Inscription: across the bottom: AVE MARIA GRATIA PLENA DOMINUS [TECUM] (Hail, Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee; from Luke 1:28); on the book held by the Redeemer in the gable: EGO SUM / A[ET] O PRINCI / PIU[M] [ET] FINIS / EGO SUM VI / A. VERITAS / [ET] VITA (I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end, I am the way, the truth, and the life; from John 14:6; Revelations 22:13) Andrew W. Mellon Collection 1937.1.4.b ENTRY This panel is the central part of a triptych flanked by two laterals with paired saints (Saint Andrew and Saint Benedict with the Archangel Gabriel [left panel] and Saint Bernard and Saint Catherine of Alexandria with the Virgin of the Annunciation [right panel]). All three panels are topped with similar triangular gables with a painted medallion in the center. The reduction of a five-part altarpiece into a simplified format with the external profile of a triptych may have been suggested to Florentine masters as a consequence of trends that appeared towards the end of the fourteenth century: a greater simplification in composition and a revival of elements of painting from the first half of the Trecento. [1] Agnolo Gaddi followed this trend in several of his works. -

Scolaio Di Giovanni (Master of Borgo Alla Collina)

Scolaio di Giovanni (Master of Borgo alla Collina) (Florence 1369-1434) Ca. 1405-1410 Madonna with Child worshiped by two angels and Saint Francis of Assisi and Julianus Tempera on wood. 93 x 52 cm Provenance: Collection F. von Wolff-Ebenrod 1920s; Private property in succession, North Rhine-Westphalia Bibliography: unpublished Cited Literature: A.Bernacchioni, in Mater Christi Austellungskatalog (Arezzo 1996), Cinisello Balsamo 1996, p.46; Alberto Lenza, Il Maestro di Borgo all Collina.Proposte per Scolaio di Giovanni pittore tardogotico fiorentino, Florence 2012; Gaudenz.Freuler, in: Gherardo di jacopo Starnina, in: The Middle Ages and early Renaissance Paintings and Sculptures from the Carlo De Carlo Collection and other Provenance, Florence 2011, p. 58-67; Lorenzo Monaco.Dalla tradizione giottesca al Rinascimento, (exhibition catalogue, Florenz Galleria dell’ Accademia 2006), Florence 2006 Our Lady stands before the shimmering golden ground. Her face is tenderly turned towards the boy Jesus, whom she holds lovingly embraced in her arms. In a childlike emotion, he reaches with his left hand for the tip of her white headscarf, while he starts to suck his thumb on the other one. With his lively gaze directed at the viewer, he communicates with him and places him in a state of contemplative meditation. Two angels in profile as well as the Franciscan founder of the Order, Francis of Assisi, and Julianus, dressed in a noble ermine-lined red cloak, are also witnesses of this intimate divine gathering of Mother of God and Child. The unknown Florentine gold ground image, which has been withheld from research so far, shows some changes; with the exception of the original preserved aureoles, the gold ground in particular has been restored and some abrasions and losses of the upper painting layer are visible.