Women's Studies — to Interpret Or Change the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Working-Class Experience in Contemporary Australian Poetry

The Working-Class Experience in Contemporary Australian Poetry A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sarah Attfield BCA (Hons) University of Technology, Sydney August 2007 i Acknowledgements Before the conventional thanking of individuals who have assisted in the writing of this thesis, I want to acknowledge my class background. Completing a PhD is not the usual path for someone who has grown up in public housing and experienced childhood as a welfare dependent. The majority of my cohort from Chingford Hall Estate did not complete school beyond Year 10. As far as I am aware, I am the only one among my Estate peers to have a degree and definitely the only one to have attempted a PhD. Having a tertiary education has set me apart from my peers in many ways, and I no longer live on the Estate (although my mother and old neighbours are still there). But when I go back to visit, my old friends and neighbours are interested in my education and they congratulate me on my achievements. When I explain that I’m writing about people like them – about stories they can relate to, they are pleased. The fact that I can discuss my research with my family, old school friends and neighbours is really important. If they couldn’t understand my work there would be little reason for me to continue. My life has been shaped by my class. It has affected my education, my opportunities and my outlook on life. I don’t look back at the hardship with a fuzzy sense of nostalgia, and I will be forever angry at the class system that held so many of us back, but I am proud of my working-class family, friends and neighbourhood. -

Proposed Redistribution of Victoria Into Electoral Divisions: April 2017

Proposed redistribution of Victoria into electoral divisions APRIL 2018 Report of the Redistribution Committee for Victoria Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 Feedback and enquiries Feedback on this report is welcome and should be directed to the contact officer. Contact officer National Redistributions Manager Roll Management and Community Engagement Branch Australian Electoral Commission 50 Marcus Clarke Street Canberra ACT 2600 Locked Bag 4007 Canberra ACT 2601 Telephone: 02 6271 4411 Fax: 02 6215 9999 Email: [email protected] AEC website www.aec.gov.au Accessible services Visit the AEC website for telephone interpreter services in other languages. Readers who are deaf or have a hearing or speech impairment can contact the AEC through the National Relay Service (NRS): – TTY users phone 133 677 and ask for 13 23 26 – Speak and Listen users phone 1300 555 727 and ask for 13 23 26 – Internet relay users connect to the NRS and ask for 13 23 26 ISBN: 978-1-921427-58-9 © Commonwealth of Australia 2018 © Victoria 2018 The report should be cited as Redistribution Committee for Victoria, Proposed redistribution of Victoria into electoral divisions. 18_0990 The Redistribution Committee for Victoria (the Redistribution Committee) has undertaken a proposed redistribution of Victoria. In developing the redistribution proposal, the Redistribution Committee has satisfied itself that the proposed electoral divisions meet the requirements of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (the Electoral Act). The Redistribution Committee commends its redistribution -

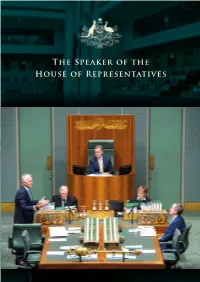

The Speaker of the House of Representatives the Speaker of the House of Representatives the Speaker of the House of Representatives

The Speaker of the House of Representatives of the House of The Speaker The Speaker of the House of Representatives The Speaker of the House of Representatives 1 © Commonwealth of Australia 2016 ISBN 978-1-74366-502-2 Printed version Prepared by the Department of the House of Representatives Photos of certain former Speakers courtesy of The National Library of Australia and Auspic/DPS (David Foote) 2 THE SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES The Speaker of the House of Representatives is the Honourable Tony Smith MP. He was elected as Speaker on 10 August 2015. Mr Smith, the Federal Member for Casey, was first elected in 2001, and re-elected at each subsequent election. The Victorian electoral division of Casey covers an area of approximately 2,500 square kilometres, extending from the outer eastern suburbs of Melbourne into the Yarra Valley and Dandenong Ranges. Industries in the electorate include market gardens, orchards, nurseries, flower farms, vineyards, forestry and timber, tourism, light manufacturing and engineering. The Speaker has previously served as the Parliamentary Secretary to the Prime Minister from 30 January 2007 to 3 December 2007, and in a range of Shadow Ministerial positions in the 42nd and 43rd parliaments. Mr Smith has also served on numerous parliamentary committees and was most recently Chair of the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters in the 44th Parliament. The Speaker studied a Bachelor of Arts (Hons) and Bachelor of Commerce at the University of Melbourne. The Speaker is married to Pam and has two sons, Thomas and Angus. THE OFFICE OF SPEAKER The Speakership is the most important office in the House of Representatives and the Speaker, the principal office holder. -

The Rise of the Australian Greens

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services Parliamentary Library Information, analysis and advice for the Parliament RESEARCH PAPER www.aph.gov.au/library 22 September 2008, no. 8, 2008–09, ISSN 1834-9854 The rise of the Australian Greens Scott Bennett Politics and Public Administration Section Executive summary The first Australian candidates to contest an election on a clearly-espoused environmental policy were members of the United Tasmania Group in the 1972 Tasmanian election. Concerns for the environment saw the emergence in the 1980s of a number of environmental groups, some contested elections, with successes in Western Australia and Tasmania. An important development was the emergence in the next decade of the Australian Greens as a unified political force, with Franklin Dam activist and Tasmanian MP, Bob Brown, as its nationally-recognised leader. The 2004 and 2007 Commonwealth elections have resulted in five Australian Green Senators in the 42nd Parliament, the best return to date. This paper discusses the electoral support that Australian Greens candidates have developed, including: • the emergence of environmental politics is placed in its historical context • the rise of voter support for environmental candidates • an analysis of Australian Greens voters—who they are, where they live and the motivations they have for casting their votes for this party • an analysis of the difficulties such a party has in winning lower house seats in Australia, which is especially related to the use of Preferential Voting for most elections • the strategic problems that the Australian Greens—and any ‘third force’—have in the Australian political setting • the decline of the Australian Democrats that has aided the Australian Greens upsurge and • the question whether the Australian Greens will ever be more than an important ‘third force’ in Australian politics. -

Thesis August

Chapter 1 Introduction Section 1.1: ‘A fit place for women’? Section 1.2: Problems of sex, gender and parliament Section 1.3: Gender and the Parliament, 1995-1999 Section 1.4: Expectations on female MPs Section 1.5: Outline of the thesis Section 1.1: ‘A fit place for women’? The Sydney Morning Herald of 27 August 1925 reported the first speech given by a female Member of Parliament (hereafter MP) in New South Wales. In the Legislative Assembly on the previous day, Millicent Preston-Stanley, Nationalist Party Member for the Eastern Suburbs, created history. According to the Herald: ‘Miss Stanley proceeded to illumine the House with a few little shafts of humour. “For many years”, she said, “I have in this House looked down upon honourable members from above. And I have wondered how so many old women have managed to get here - not only to get here, but to stay here”. The Herald continued: ‘The House figuratively rocked with laughter. Miss Stanley hastened to explain herself. “I am referring”, she said amidst further laughter, “not to the physical age of the old gentlemen in question, but to their mental age, and to that obvious vacuity of mind which characterises the old gentlemen to whom I have referred”. Members obviously could not afford to manifest any deep sense of injury because of a woman’s banter. They laughed instead’. Preston-Stanley’s speech marks an important point in gender politics. It introduced female participation in the Twenty-seventh Parliament. It stands chronologically midway between the introduction of responsible government in the 1850s and the Fifty-first Parliament elected in March 1995. -

Chicago's Torture Machine and Reparations Palestine

Burma: War vs. the People w Behind Detroit’s Labor History #213 • JULY/AUGUST 2021 • $5 Chicago’s Torture Machine and Reparations w AISLINN PULLEY w MARK CLEMENTS w JOEY MOGUL w LINDA LOEW Palestine — Then and Now w MALIK MIAH w MOSHE MACHOVER w DAVID FINKEL w MERRY MAISEL w DON B. GREENSPON A Letter from the Editors: Infrastructure: Who Needs It? “INFRASTRUCTURE” IS ALL the rage, and not only just now. Trump talked about it, president Obama promised it, and so have administrations going back to the 1980s. Amidst the talk, the United States’ roads and bridges are crumbling, water and sanitation systems faltering, public health services left in a condition that’s only been fully exposed in the coronavirus pandemic, and rapid transit and high-speed internet access in much of the country inferior to what’s available in the rural interior of China. A combination of circumstances have changed the discussion. The objective realities include the pandemic; its devastating economic impacts most heavily on Black, brown and women’s employment; the necessity of rapid conversion to renewable energy, now clear even to much of capital — and yes, the pressures of deepening competition and rivalry with China. The obvious immediate political factors are the defeat of Trump and the ascendance of the Democrats to narrow Congressional and Senate majorities. It became clear, however, that there would be no serious results, they might well be electorally dead in 2022 Republican support for anything resembling Biden’s and beyond. That pressure, along with the party’s left wing, infrastructure program — even after he’d stripped several put some backbone into the administration’s posture hundred billion dollars and scrapped raising the corporate although the “progressive” forces certainly don’t control tax rate to pay for it. -

Keynotes, Abstracts and Biographies

Beyond the Culture Wars LGBTIQ History Now Keynotes Jagose, Annamarie, ‘Our Bodies, Our Archives Given that the term “culture wars” is a distinctively American import, when we come to thinking about how it might resonate in our Australian contexts, it is worth keeping in mind the materiality of place. After some consideration of my own embroilment in cultural contestation regarding my queer research program, I return to this notion of the materiality of place to suggest that the archive offers us capacious opportunities for engagement that move beyond the agonistic stand-offs associated with what Janice Irvine describes as the “recursive, unyielding civic arguments popularly known as culture wars.” Bio: Annamarie Jagose is internationally known as a scholar in feminist studies, lesbian/gay studies and queer theory. She is the author of four monographs, most recently Orgasmology, which takes orgasm as its scholarly object in order to think queerly about questions of politics and pleasure; practice and subjectivity; agency and ethics. She is also an award-winning novelist and short story writer. Wilcox, Melissa, ‘Apocrypha and Sacred Stories: Queer Worldmaking, Historical “Truth,” and the Ethics of Research in Living Communities’ While historical research may always have contemporary consequences, in that the tales one tells of the past are rarely inert or disinterested in the present day, the epistemological and ethical challenges of historical research within living communities are particularly marked. The field of religious studies offers one framework for thinking through such challenges in its long-standing attention to the potency of sacred story, whether specifically religious or not, for the enterprise of worldmaking. -

Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Twenty-Four

Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Twenty-four Proceedings of the Twenty-fourth Conference of The Samuel Griffith Society Traders Hotel Brisbane, 159 Roma Street, Hobart — August 2012 © Copyright 2014 by The Samuel Griffith Society. All rights reserved. Contents Introduction Julian Leeser The Fourth Sir Harry Gibbs Memorial Oration Senator the Honourable George Brandis In Defence of Freedom of Speech Chapter One The Honourable Ian Callinan Defamation, Privacy, the Finkelstein Report and the Regulation of the Media Chapter Two Michael Sexton Flights of Fancy: The Implied Freedom of Political Communication 20 Years On Chapter Three The Honourable Justice J. D. Heydon Sir Samuel Griffith and the Making of the Australian Constitution Chapter Four The Honourable Christian Porter Federal-State Relations and the Changing Economy Chapter Five The Honourable Richard Court A Federalist Agenda for Coast to Coast Liberal (or Labor) Governments Chapter Six Keith Kendall The Case for a State Income Tax Chapter Seven Josephine Kelly The Constitutionality of the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act i Chapter Eight The Honourable Gary Johns Native Title 20 Years On: Beyond the Hyperbole Chapter Nine Lorraine Finlay Indigenous Recognition – Some Issues Chapter Ten J. B. Paul Speaker of the House Contributors ii Introduction Julian Leeser The 24th Conference of The Samuel Griffith Society was held in Brisbane during the weekend of 17-19 August 2012. It marked the 20th anniversary of the Society’s birth. 1992 was undoubtedly a momentous year in Australia’s constitutional history. On 2 January 1992 the perspicacious John and Nancy Stone decided to incorporate the Samuel Griffith Society thirteen days after Paul Keating was appointed Prime Minister. -

Inaugural Speech I Commence by Acknowledging the Traditional Owners of the Land Upon Which This House Rests and Has Met for the Last 150 Years

Michelle O’Byrne MP House of Assembly Date: 30 May 2006 Electorate: Bass ADDRESS-IN-REPLY Ms O'BYRNE (Bass - Inaugural) - Mr Speaker, I have the honour to move - That the following address be presented to His Excellency the Governor in reply to His Excellency's speech. To His Excellency the Honourable William John Ellis Cox, Companion of the Order of Australia, Governor in and over the State of Tasmania and its dependencies in the Commonwealth of Australia: MAY IT PLEASE YOUR EXCELLENCY: We, Her Majesty's dutiful and loyal subjects, the members of the House of Assembly of Tasmania, in Parliament assembled, desire to thank Your Excellency for the speech which you have been pleased to address to both Houses of Parliament. We desire to record our continued loyalty to the Throne and Person of Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth the Second, and at the same time assure Your Excellency that the measures which will be laid before us during the session will receive our careful consideration. Mr Speaker, in this my inaugural speech I commence by acknowledging the traditional owners of the land upon which this House rests and has met for the last 150 years. I congratulate all members of the House on their election. To my colleague, the member for Denison, Ms Singh, I extend particularly warm congratulations on her first election to this place. I am not the first member of parliament to be given the opportunity to make a second first speech. It is in fact a reasonably common occurrence for Australians in public office to serve first in the Federal Parliament and then at a State level, or vice versa. -

House of Representatives Official Hansard No

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES House of Representatives Official Hansard No. 1, 2010 Wednesday, 29 September 2010 FORTY-THIRD PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—FIRST PERIOD BY AUTHORITY OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES INTERNET The Votes and Proceedings for the House of Representatives are available at http://www.aph.gov.au/house/info/votes Proof and Official Hansards for the House of Representatives, the Senate and committee hearings are available at http://www.aph.gov.au/hansard For searching purposes use http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au SITTING DAYS—2010 Month Date February 2, 3, 4, 8, 9, 10, 11, 22, 23, 24, 25 March 9, 10, 11, 15, 16, 17, 18 May 11, 12, 13, 24, 25, 26, 27, 31 June 1, 2, 3, 15, 16, 17, 21, 22, 23, 24 September 28, 29, 30 October 18, 19, 20, 21, 25, 26, 27, 28 November 15, 16, 17, 18, 22, 23, 24, 25 RADIO BROADCASTS Broadcasts of proceedings of the Parliament can be heard on ABC NewsRadio in the capital cities on: ADELAIDE 972AM BRISBANE 936AM CANBERRA 103.9FM DARWIN 102.5FM HOBART 747AM MELBOURNE 1026AM PERTH 585AM SYDNEY 630AM For information regarding frequencies in other locations please visit http://www.abc.net.au/newsradio/listen/frequencies.htm FORTY-THIRD PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION—FIRST PERIOD Governor-General Her Excellency Ms Quentin Bryce, Companion of the Order of Australia House of Representatives Officeholders Speaker—Mr Harry Alfred Jenkins MP Deputy Speaker— Hon. Peter Neil Slipper MP Second Deputy Speaker—Hon. Bruce Craig Scott MP Members of the Speaker’s Panel—Hon. Dick Godfrey Harry Adams MP, Ms Sharon Leah Bird MP, Mr Steven Georganas MP, Mr Peter Sid Sidebottom MP Leader of the House—Hon. -

Selected Australian Political Records

RESEARCH PAPER SERIES, 2013–14 UPDATED 5 MARCH 2014 Selected political records of the Commonwealth Parliament Martin Lumb and Rob Lundie Politics and Public Administration Contents Introduction ................................................................................................ 6 Governor-General ....................................................................................... 6 First Governor-General..................................................................................... 6 First Australian-born Governor-General .......................................................... 6 Prime Ministers ........................................................................................... 6 First Prime Minister .......................................................................................... 6 First Leader of the Opposition .......................................................................... 6 Youngest person to become Prime Minister .................................................... 6 Oldest person to become Prime Minister ........................................................ 6 Longest serving Prime Minister ........................................................................ 6 Shortest serving Prime Minister ....................................................................... 6 Oldest serving Prime Minister .......................................................................... 6 Prime Ministers who served separate terms as Prime Minister ...................... 6 Prime Ministers who -

A Current Listing of Contents Volume 3, Number 3, 1983

a current listing of contents Volume 3, Number 3, 1983 Published by Susan Searing, Women's Studies Librarian-at-Large, University of Wisconsin System 112A Memorial Library 728 State Street Madison, Wisconsin 53706 (608) 263- 5754 a current list in^ of contents Volume 3, Number 3, 1983 Periodical 1i terature is the cutting edge of women Is scholarship, feminist theory, and much of women's culture. Feminist Periodicals: A Current Listing of Contents is published by the Office of the Women's Studies Librarian-at-Large on a quarterly basis with the intent of increasing public awareness of feminist periodicals. It is our hope that Feminist Periodicals will serve several purposes: to keep the reader abreast of current topics in feminist literature; to increase readers' familiarity with a wide spectrum of feminist periodicals; and to pro- vide the requisite bibliographic information should a reader wish to subscribe to a journal or to obtain a particular article at her library or through interlibrary loan. (Users will need to be aware of the limitations of the new copyright law with regard to photocopying of .copyrighted materials.) Table of contents pages from current issues of major feminist journals - are reproduced in each issue of Feminist Periodicals, preceded by a comprehensive annotated 1isting of a1 1 journals we have selected. As publ ication schedules vary enormously, not every periodical wi11 have table of contents pages reproduced in each issue of FP. The annotated 1isting provides the following information on each journal : Year of first publ ication. Frequency of publication. a U.S. subscription price(s) .