Porphyria and Anorexia: Cause and Effect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clinical and Biochemical Characteristics and Genotype – Phenotype Correlation in Finnish Variegate Porphyria Patients

European Journal of Human Genetics (2002) 10, 649 – 657 ª 2002 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 1018 – 4813/02 $25.00 www.nature.com/ejhg ARTICLE Clinical and biochemical characteristics and genotype – phenotype correlation in Finnish variegate porphyria patients Mikael von und zu Fraunberg*,1, Kaisa Timonen2, Pertti Mustajoki1 and Raili Kauppinen1 1Department of Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, University Central Hospital of Helsinki, Biomedicum Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland; 2Department of Dermatology, University Central Hospital of Helsinki, Biomedicum Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland Variegate porphyria (VP) is an inherited metabolic disease resulting from the partial deficiency of protoporphyrinogen oxidase, the penultimate enzyme in the heme biosynthetic pathway. We have evaluated the clinical and biochemical outcome of 103 Finnish VP patients diagnosed between 1966 and 2001. Fifty-two per cent of patients had experienced clinical symptoms: 40% had photosensitivity, 27% acute attacks and 14% both manifestations. The proportion of patients with acute attacks has decreased dramatically from 38 to 14% in patients diagnosed before and after 1980, whereas the prevalence of skin symptoms had decreased only subtly from 45 to 34%. We have studied the correlation between PPOX genotype and clinical outcome of 90 patients with the three most common Finnish mutations I12T, R152C and 338G?C. The patients with the I12T mutation experienced no photosensitivity and acute attacks were rare (8%). Therefore, the occurrence of photosensitivity was lower in the I12T group compared to the R152C group (P=0.001), whereas no significant differences between the R152C and 338G?C groups could be observed. Biochemical abnormalities were significantly milder suggesting a milder form of the disease in patients with the I12T mutation. -

IS IT AIP Symptoms Checker Summary

Acute Intermittent Porphyria: Symptoms, Triggers, and Other Factors Common symptoms of acute intermittent porphyria (AIP) AIP can cause many different symptoms that tend to come and go. When someone with AIP has symptoms, the episode is called an AIP attack. A person may have certain symptoms during one attack but different symptoms during another attack. Severe abdominal pain • Severe abdominal pain is the most common symptom of AIP. More than 85% of people have abdominal pain during AIP attacks. • The pain often lasts for hours or days. • The pain tends to begin slowly and become worse. • The pain tends to be all over and not in one small area. • The pain may start in the chest or back and move to the abdomen. • Pain medicines such as Advil® (ibuprofen) or Tylenol® (acetaminophen) usually don’t help much. This is because the pain is caused by nerves. Nausea or vomiting • Nausea or vomiting is common during AIP attacks. • People with AIP often have nausea or vomiting along with abdominal pain. Constipation • Constipation is common during AIP attacks. • Loss of bladder control may go along with constipation. Dark or reddish urine • Urine that turns reddish or dark over time when exposed to light and air is common during AIP attacks. • The change in urine color is due to certain chemicals in the urine during AIP attacks. Muscle weakness • Muscle weakness is common during AIP attacks. • Muscle weakness usually begins in the arms and often in the shoulders. 1 Common symptoms of AIP (cont.) Pain in the arms, legs, back, chest, neck, or head • Abdominal pain is the most common symptom of AIP. -

Porphyria: a Difficult Disease to Diagnose by Marelda Abney RN

1 Porphyria: A difficult disease to diagnose By Marelda Abney RN, BSN A Manuscript submitted in partial fulfillment ofthe requirement for the degree Master ofNursing Washington State University Intercollegiate College ofNursing Spokane, Washington July 2003 11 To the faculty ofWashington State University: The members ofthe committee appointed to examine the Intercollegiate College of Nursing research requirements and manuscript of MARELDA MARY ABNEY fmd it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. ,~~ 5ctl(.~~v~ Lorna Schumann, PhD, FAANP, ARNP ~~ 2u J:~ AhJ5uv Billie Severtsen, PhD, RN _~-/A~-t~£0 Sheila Masteller, MN, BSN, RN 111 Acknowledgements I would like to thank everyone who has supported me in one way or another in completing my manuscript and fulfilling my dream ofbecoming a family nurse practitioner. My deepest gratitude goes out to those who served on my committee for my clinical project. Dr. Billie Severtsen, committee member, whom I fIrst met in my undergraduate program. She was an inspiration then as she is now, in the ways ofmedical ethics and compassionate care. I have been forttmate to have had her be a part ofmy education from the beginning ofmy career through to the end ofthis project. Sheila Masteller, committee nlember and role model. I have been privileged to work with Sheila at Visiting Nurses Association where she is president and an exemplary leader in home health care. Her concern for the welfare ofpatients and staffhas made her the ideal example of leadership. Lorna Schumann, committee member and mentor. Lorna has always been there for me as I struggled down this path. She has listened when I just needed to talk which is a priceless gift. -

Safe Use of Sodium Valproate

VOLUME 37 : NUMBER 4 : AUGUST 2014 ARTICLE Safe use of sodium valproate Ahamed Zawab Advanced trainee1 SUMMARY John Carmody Staff specialist1 Valproate is an anticonvulsant drug which is approved for use in epilepsy and bipolar disorder. It Clinical associate professor2 has also been used for neuropathic pain and migraine prophylaxis. 1 Neurology Department Gastrointestinal adverse effects are common, particularly at the start of therapy. Important Wollongong Hospital adverse effects include pancreatitis, hepatitis, weight gain and sedation. There is an increased risk 2 Graduate School of Medicine of fetal abnormalities if valproate is taken in pregnancy. University of Wollongong Measuring concentrations of serum valproate is often unnecessary. They do not correlate closely New South Wales with its therapeutic effects. Key words If withdrawal of valproate is required, this should be done slowly if possible. Rapid cessation may adverse effects, bipolar provoke seizures in patients with epilepsy. disorder, birth defects, epilepsy Introduction Indications Aust Prescr 2014;37:124–7 Sodium valproate (valproate) was first marketed as Although there is clinical experience with valproate in an anticonvulsant almost 50 years ago in France. Its epilepsy, some of its other accepted indications, such indications have expanded and it is now the most as migraine prophylaxis, have not been approved by prescribed antiepileptic drug worldwide.1 However, it the Therapeutic Goods Administration. has many potential adverse effects. Epilepsy Pharmacology Valproate is a broad spectrum antiepileptic drug and Valproate is available in tablet (immediate-release or is used to treat either generalised or focal seizures. This article has a continuing 4 5-7 professional development enteric coated), syrup and intravenous formulations. -

The Little Imitator-Porphyria: a Neuropsychiatric Disorder

Journal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1997;62:319-328 319 REVIEW J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.62.4.319 on 1 April 1997. Downloaded from The little imitator-porphyria: a neuropsychiatric disorder Helen L Crimlisk Abstract Porphyria is derived from the Greek word por- Three common subtypes of porphyria phuros meaning purple. Protoporphyrin IX is give rise to neuropsychiatric disorders; the biologically active substance, an important acute intermittent porphyria, variegate feature of which is its metal binding capacity. porphyria, and coproporphyria. The sec- Both chlorophyll and haem are metallopor- ond two also give rise to cutaneous symp- phyrins and are involved in the processes of toms. Neurological or psychiatric energy capture and utilisation in animals and symptoms occur in most acute attacks, plants. The description of the porphyrins by and may mimc many other disorders. Nobel laureate Hans Fischer' in 1930 as: The diagnosis may be missed because it is "The compounds which make grass green not even considered or because of techni- and blood red." cal problems, such as sample collection indicates the central position of these sub- and storage, and interpretation of results. stances in the biological sciences. A negative screening test does not exclude The porphyrias are a heterogeneous group the diagnosis. Porphyria may be overrep- of overproduction diseases, resulting from resented in psychiatric populations, but genetically determined, partial deficiencies in the lack of control groups makes this haem biosynthetic enzymes. Their manifesta- Department of uncertain. The management of patients tions are broad and their relevance in neu- Neuropsychiatry, with porphyria and psychiatric symptoms ropsychiatric disorders may sometimes be Institute ofNeurology, causes considerable Queen Square, problems. -

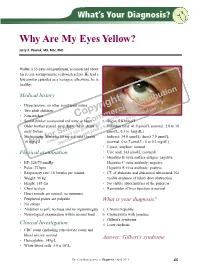

Copyright Why Are My Eyes Yellow?

What’s Your Diagnosis? Why Are My Eyes Yellow? Jerzy K. Pawlak, MD, MSc, PhD Walter, a 55-year-old gentleman, is concerned about his recent asymptomatic yellowish sclera. He had a few similar episodes as a teenager; otherwise, he is healthy. tion Medical history © ibu t tr ad, h is nlo • Hypertension; no other significant issues g D ow ri l n d e • Two adult children y ia ca us p rc ers nal o e us rso • Non-smoker C m ised r pe m hor y fo • Social drinker (occasional red wine or beer) o A• uStugar: 5o.p8 mmol/L C d. le c r ite ing • Older brother passed away due to oheart athtaicbk in a•s Bilirubin total: 41.0 µmol/L (normal: 2.0 to 18 le pro int early forties a use pr µmol/L; 0.1 to 1mg/dL) S ed and • Medications: Moicardis 8o0rmisg q.di.eawnd Crestor Indirect: 34.0 µmol/L; direct 7.0 µmol/L f uth y, v ot na pla 10 mNg q.d. U dis (normal: 0 to 7 µmol/L; 0 to 0.2 mg/dL) • Lipase, amylase: normal Physical examination • Uric acid: 343 µmol/L (normal) • Hepatitis B virus surface antigen: negative • BP: 128/79 mmHg Hepatitis C virus antibody: negative • Pulse: 72 bpm Hepatitis A virus antibody: positive • Respiratory rate: 18 breaths per minute • CT of abdomen and abdominal ultrasound: No • Weight: 90 kg visible evidence of bilary duct obstruction • Height: 185 cm • No visible abnormalities of the pancreas • Chest is clear • Remainder of liver function is normal • Heart sounds are normal, no murmurs • Peripheral pulses are palpable What is your diagnosis? • No edema • Abdomen is soft; no mass and no organomegaly a. -

Porphyria and Its Neurologic Manifestations

Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Vol. 120 (3rd series) Neurologic Aspects of Systemic Disease Part II Jose Biller and Jose M. Ferro, Editors © 2014 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved Chapter 56 Porphyria and its neurologic manifestations JENNIFER A. TRACY AND P. JAMES B. DYCK* Mayo Clinic, Department of Neurology, Rochester, MN, USA INTRODUCTION the biochemical processes of porphyrin formation and the defects along the heme biosynthetic pathway. Porphyrias are rare disorders of heme metabolism, each The porphyrias are disorders of heme metabolism, characterized by a defect in an enzyme required for the caused by a defect in an enzyme responsible for the syn- synthesis of heme. These disorders can produce distur- thesis of the heme molecule, which in turn is necessary bances of multiple organ systems, including the skin, for the production of hemoglobin, myoglobin, and cyto- liver, and central and peripheral nervous systems. The chromes. Heme is an oxygen carrier, and is essential for types of porphyria typically implicated in neurologic dis- aerobic respiration and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) ease are acute intermittent porphyria, hereditary copro- production via the electron transport chain. Cytochrome porphyria, and variegate porphyria, which are all production is necessary for metabolism of multiple autosomal dominant inherited conditions. These are gen- drugs within the body, most notably through the cyto- erally characterized by neuropsychiatric symptoms with chrome P450 system, and also mediates the removal of mood disorder and/or psychosis, peripheral neuropathy some toxic substances. Adequate heme formation is (generally motor-predominant), gastrointestinal distur- extremely important for the health of the individual, bances, and (in the case of variegate porphyria and some- both in terms of energy production and metabolism, times hereditary coproporphyria) photosensitivity and and abnormalities can have a profound impact. -

![Valproic Acid) Solution Depakene (Valproic Acid) Capsule, Liquid Filled [Abbott Laboratories]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8712/valproic-acid-solution-depakene-valproic-acid-capsule-liquid-filled-abbott-laboratories-4438712.webp)

Valproic Acid) Solution Depakene (Valproic Acid) Capsule, Liquid Filled [Abbott Laboratories]

Depakene (valproic acid) Solution Depakene (valproic acid) Capsule, Liquid Filled [Abbott Laboratories] BOX WARNING HEPATOTOXICITY HEPATIC FAILURE RESULTING IN FATALITIES HAS OCCURRED IN PATIENTS RECEIVING VALPROIC ACID. EXPERIENCE HAS INDICATED THAT CHILDREN UNDER THE AGE OF TWO YEARS ARE AT A CONSIDERABLY INCREASED RISK OF DEVELOPING FATAL HEPATOTOXICITY, ESPECIALLY THOSE ON MULTIPLE ANTICONVULSANTS, THOSE WITH CONGENITAL METABOLIC DISORDERS, THOSE WITH SEVERE SEIZURE DISORDERS ACCOMPANIED BY MENTAL RETARDATION, AND THOSE WITH ORGANIC BRAIN DISEASE. WHEN DEPAKENE PRODUCTS ARE USED IN THIS PATIENT GROUP, THEY SHOULD BE USED WITH EXTREME CAUTION AND AS A SOLE AGENT. THE BENEFITS OF THERAPY SHOULD BE WEIGHED AGAINST THE RISKS. ABOVE THIS AGE GROUP, EXPERIENCE IN EPILEPSY HAS INDICATED THAT THE INCIDENCE OF FATAL HEPATOTOXICITY DECREASES CONSIDERABLY IN PROGRESSIVELY OLDER PATIENT GROUPS. THESE INCIDENTS USUALLY HAVE OCCURRED DURING THE FIRST SIX MONTHS OF TREATMENT. SERIOUS OR FATAL HEPATOTOXICITY MAY BE PRECEDED BY NON-SPECIFIC SYMPTOMS SUCH AS MALAISE, WEAKNESS, LETHARGY, FACIAL EDEMA, ANOREXIA, AND VOMITING. IN PATIENTS WITH EPILEPSY, A LOSS OF SEIZURE CONTROL MAY ALSO OCCUR. PATIENTS SHOULD BE MONITORED CLOSELY FOR APPEARANCE OF THESE SYMPTOMS. LIVER FUNCTION TESTS SHOULD BE PERFORMED PRIOR TO THERAPY AND AT FREQUENT INTERVALS THEREAFTER, ESPECIALLY DURING THE FIRST SIX MONTHS. TERATOGENICITY VALPROATE CAN PRODUCE TERATOGENIC EFFECTS SUCH AS NEURAL TUBE DEFECTS (E.G., SPINA BIFIDA). ACCORDINGLY, THE USE OF VALPROATE PRODUCTS IN WOMEN OF CHILDBEARING POTENTIAL REQUIRES THAT THE BENEFITS OF ITS USE BE WEIGHED AGAINST THE RISK OF INJURY TO THE FETUS. THIS IS ESPECIALLY IMPORTANT WHEN THE TREATMENT OF A SPONTANEOUSLY REVERSIBLE CONDITION NOT ORDINARILY ASSOCIATED WITH PERMANENT INJURY OR RISK OF DEATH (E.G., MIGRAINE) IS CONTEMPLATED. -

Porphyria Everything You Need to Know ....Well Almost!

Porphyria Everything you need to know ....well almost! Cerys Lockett UKPMIS, WMIC, Cardiff Definition of Porphyria Porphyrias are a group of inherited metabolic disorders of the haem biosynthesis pathway, caused by a deficiency of one of the eight enzymes involved, leading to accumulation of neurotoxic or phototoxic haem precursors. The conditions are characterised by acute neurovisceral crises, skin lesions or both. Haem biosynthesis pathway Ref: http://www.stepwards.com/wp- content/uploads/2015/12/porphyria-9-638.jpg Types of porphyria ACUTE PORPHYRIAS NON-ACUTE PORPHYRIAS AIP = Acute intermittent PCT = porphyria cutanea porphyria tarda VP = Variegate porphyria EPP = erythropoietic HCP = Hereditary protoporphyria coproporphyria CEP = congenital ALAD-deficiency porphyria = erythropoietic porphyria 5-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase deficiency porphyria There are many types of porphyria. What type of porphyria does your patient have? Mechanism of an acute attack • Acute porphyrias (AIP, VP and HCP) are conditions that can present with acute porphyria attacks. • Due to the genetic defect there is a deficiency in one of the enzymes so patients have a rate limiting step in the biosynthetic pathway during periods of increased requirements of hepatic haem biosynthesis. • Although haem is produced, it is at the expense of excessive production of neurotoxic precursors, porphyrins, 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) and porphobilinogens (PBGs). • The consequence of which is the range of symptoms • Many things can increase requirements of hepatic haem -

Porphyrin Metabolism and Haem Biosynthesis in Gilbert's Syndrome

Gut: first published as 10.1136/gut.28.2.125 on 1 February 1987. Downloaded from Gut, 1987, 28, 125-130 Porphyrin metabolism and haem biosynthesis in Gilbert's syndrome K E L McCOLL, G G THOMPSON, E EL OMAR, M R MOORE, AND A GOLDBERG From the University Dept. Medicine, Gardiner Institute, Western Infirmary, Glasgow SUMMARY Studies in 14 patients with unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia caused by Gilbert's syndrome have revealed abnormalities of the enzymes of haem biosynthesis measured in peripheral blood cells. The activity of the penultimate enzyme of haem biosynthesis protopor- phyrinogen (PROTO) oxidase was reduced at 3-1±2.6 nmol PROTO/g protein/h (mean±ISD) compared with 8*2±5-1 in controls (p<0.005). This was associated with a compensatory increase in the activity of the initial and rate controlling enzyme of the pathway delta-aminolaevulinic acid (ALA) synthase at 866±636 nmol ALA/g/protein/h compared with 156±63 in controls (p<0.001). Unlike variegate porphyria in which there is a genetic deficiency of PROTO oxidase there was no increased excretion of porphyrins or their precursors in Gilbert's syndrome. Accentuation and subsequent correction of the unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia with rifampicin produced reciprocal changes in PROTO oxidase activity indicating that bilirubin may be inhibiting the activity of this enzyme. http://gut.bmj.com/ Gilbert's syndrome originally described in 1901 by ferase activity.`8 Gilbert's syndrome may be a Gilbert and Lereboullet' is a benign disorder affect- heterogenous disorder.9 We wish to report a pre- ing 2-5% of the population. -

Porphyria As a Problem in Anaesthesia

PORPHYRIA AS A PROBLEM iIN ANAESTHESIA* F. F. LEPINSKIE, ~zs , C.M.~ Pom'Ia-xma is a discouraging disease. Even the mos~ skilfully administered anaes- thetic may have a fatal outcome in a porphyric, ifJit includds a barbiturate. It is also an uncommon disease. In the 50 years sin~e it was described, IWatson 1 collected 275 cases of all types occurring in th~ U.S.A. But the barbiturates are one of the most commonly used groups of drugs in medicine ancl it is very cliff'cult, today, for any patient to avoid exposure to them. The anaesthetist gives a barbiturate to almost every patient he seek and some iknowledge of this disease is important to him ff trouble is to be avoided. Just how important may be illustrated by the following facts. In Great Britain during the years 1948-53, 32 p~tients with acute intermittent porphyria were reported-~ of these, 13 had received thiopentone, all of the 13 developing paralysis, and 5 having a fatal outcome. Again in 1962, Dundee et al. a reported 3 cases of acute intermittent porphyria who were given thiopentone; all were paralysed, two died, and the third made 9 slow recovery after a year of physiotherapy. The maxim 'primum non nocere seems to be very applicable here. PORPHYIIIA, I~ORPHYRINLItlL~,AND TI-IE ~0RPHYRIN PIGN,IENTS The terminology of the porphyrins is apt to bej confusing to someone making their acquaintance for the first time. Porphyrin ig the Greek word for "purple" and i s the name first given -to the purple iron-free. -

Porphyria (Cutaneous) Testing Algorithm*

Porphyria (Cutaneous) Testing Algorithm* Symptom: Skin manifestations restricted to sun-exposed areas Possible cutaneous porphyria: ■ Porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) Symptoms: ■ ■ Edema Erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP) PPFE / Protoporphyrins, ■ a ■ Sun-induced erythema Variegate porphyria (VP) Fractionation, Whole Blood ■ Hereditary coproporphyria (HCP)b ■ Acute painful photodermatitis ■ Congenital erythropoietic porphyria (CEP) ■ Urticaria ■ X-linked dominant protoporphyria (XLDPP) Normal Increased zinc Increased free Increased free and Symptoms: protoporphyrin protoporphyrin zinc protoporphyrins ■ Blistering lesions or bullae (>40% zinc ■ Skin fragility protoporphyrin) ■ Scarring Excludes EPP Consider: ■ EPP ■ Hyper/hypopigmentation ■ Iron de ciency anemia ■ Family studies ■ Possible hypertrichosis If clinically indicated ■ Heavy metal may be warranted intoxication Suspicious of XLDPP ■ Anemia of chronic Excludes Normal PQNRU / Porphyrins, Quantitative, disease FECHZ / Ferrochelatase PCT and CEP Random, Urine (includes PBG) (FECH) Gene, Full Gene Analysis If clinically Increased coproporphyrin Increased uroporphyrin Increased uroporphyrin and indicated and/or PBG and uroporphyrin and coproporphyrin heptacarboxylporphyrin Mutation No mutation indentified found FQPPS / Porphyrins, Feces UPGC / Uroporphyrinogen III Synthase UPGD / Uroporphyrinogen Confirms EPP (Co-Synthase) (UPG III S), Erythrocytes Decarboxylase (UPG D), Whole Blood Increased Increased coproporphyrin III/I coproporphyrin Normal Decreased Normal Decreased Normal ratio