Judge Alonzo Conant (1914- 1962)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Maine NAACP and the Pursuit of Fair Housing Legislation

Maine History Volume 36 Number 3 Issues 3-4; Civil Rights in Maine, Article 3 1945-1971 1-1-1997 Resistance In “Pioneer Territory”: The Maine NAACP and the Pursuit of Fair Housing Legislation Eben Simmons-Miller Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal Part of the Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Simmons-Miller, Eben. "Resistance In “Pioneer Territory”: The Maine NAACP and the Pursuit of Fair Housing Legislation." Maine History 36, 3 (1996): 86-105. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/ mainehistoryjournal/vol36/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. K E E N SIM M O N S M IL L E R RESISTANCE IN “PIONEER TERRITORY”: THE MAINE NAACP AND THE PURSUIT OF FAIR HOUSING LEGISLATION While Charles Lumpkins details the organiza tional strategies of the civil-rights movement in Maine, Eben Miller focuses on the politics of fair housing. Outlining the “geography of segregation” in Maine, he describes the resistance to fair housing and the means by which the NAACP documented civil-rights viola tions, drafted legislation, built coalitions of concerned black and white citizens, and advanced the “moral and ethical responsibility ” of all Mainers to work for fair housing legislation. Mr. Miller, from Woolwich, gradu atedfrom Bates College in 1996. His article is based on research done for an honors thesis. -

New Solar Research Yukon's CKRW Is 50 Uganda

December 2019 Volume 65 No. 7 . New solar research . Yukon’s CKRW is 50 . Uganda: African monitor . Cape Greco goes silent . Radio art sells for $52m . Overseas Russian radio . Oban, Sheigra DXpeditions Hon. President* Bernard Brown, 130 Ashland Road West, Sutton-in-Ashfield, Notts. NG17 2HS Secretary* Herman Boel, Papeveld 3, B-9320 Erembodegem (Aalst), Vlaanderen (Belgium) +32-476-524258 [email protected] Treasurer* Martin Hall, Glackin, 199 Clashmore, Lochinver, Lairg, Sutherland IV27 4JQ 01571-855360 [email protected] MWN General Steve Whitt, Landsvale, High Catton, Yorkshire YO41 1EH Editor* 01759-373704 [email protected] (editorial & stop press news) Membership Paul Crankshaw, 3 North Neuk, Troon, Ayrshire KA10 6TT Secretary 01292-316008 [email protected] (all changes of name or address) MWN Despatch Peter Wells, 9 Hadlow Way, Lancing, Sussex BN15 9DE 01903 851517 [email protected] (printing/ despatch enquiries) Publisher VACANCY [email protected] (all orders for club publications & CDs) MWN Contributing Editors (* = MWC Officer; all addresses are UK unless indicated) DX Loggings Martin Hall, Glackin, 199 Clashmore, Lochinver, Lairg, Sutherland IV27 4JQ 01571-855360 [email protected] Mailbag Herman Boel, Papeveld 3, B-9320 Erembodegem (Aalst), Vlaanderen (Belgium) +32-476-524258 [email protected] Home Front John Williams, 100 Gravel Lane, Hemel Hempstead, Herts HP1 1SB 01442-408567 [email protected] Eurolog John Williams, 100 Gravel Lane, Hemel Hempstead, Herts HP1 1SB World News Ton Timmerman, H. Heijermanspln 10, 2024 JJ Haarlem, The Netherlands [email protected] Beacons/Utility Desk VACANCY [email protected] Central American Tore Larsson, Frejagatan 14A, SE-521 43 Falköping, Sweden Desk +-46-515-13702 fax: 00-46-515-723519 [email protected] S. -

Catalogue of the Athenaean Society of Bowdoin College

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine History Documents Special Collections 1844 Catalogue of the Athenaean Society of Bowdoin College Athenaean Society (Bowdoin College) Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory Part of the History Commons This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pamp 285 CATALOGUE OF THE ATHENANE SOCIETY BOWDOIN COLLEGE. INSTITUTED M DCCC XVII~~~INCORFORATED M DCCC XXVIII. BRUNSWICK: PRESS OF JOSEPH GRIFFIN. 1844. RAYMOND H. FOGLER LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MAINE ORONO, MAINE from Library Number, OFFICERS OF THE GENERAL SOCIETY. Presidents. 1818 LEVI STOWELL . 1820 1820 JAMES LORING CHILD . 1821 1821 *WILLIAM KING PORTER . 1822 1822 EDWARD EMERSON BOURNE . 1823 1823 EDMUND THEODORE BRIDGE . 1825 1825 JAMES M’KEEN .... 1828 1828 JAMES LORING CHILD . 1829 1829 JAMES M’KEEN .... 1830 1830 WILLIAM PITT FESSENDEN . 1833 1833 PATRICK HENRY GREENLEAF . 1835 1835 *MOSES EMERY WOODMAN . 1837 1837 PHINEHAS BARNES . 1839 1839 WILLIAM HENRY ALLEN . 1841 1841 HENRY BOYNTON SMITH . 1842 1842 DANIEL RAYNES GOODWIN * Deceased. 4 OFFICERS OF THE Vice Presidents. 1821 EDWARD EMERSON BOURNE . 1822 1822 EDMUND THEODORE BRIDGE. 1823 1823 JOSIAH HILTON HOBBS . 1824 1824 ISRAEL WILDES BOURNE . 1825 1825 CHARLES RICHARD PORTER . 1827 1827 EBENEZER FURBUSH DEANE . 1828 In 1828 this office was abolished. Corresponding Secretaries. 1818 CHARLES RICHARD PORTER . 1823 1823 SYLVANUS WATERMAN ROBINSON . 1827 1827 *MOSES EMERY WOODMAN . 1828 In 1828 this office was united with that of the Recording Secretary. -

Sheigra Dxpedition Report

Sheigra DXpedition Report 12 th to 25 th October 2019 - with Dave Kenny & Alan Pennington This was the 58th DXpedition to Sheigra in Sutherland on the far north western tip of the Scottish mainland, just south of Cape Wrath. DXers made the first long drive up here in 1979, so this we guess, was the 40 th anniversary? And the DXers who first made the trip to Sheigra in 1979 to listen to MW would probably notice little change here today: the single-track road ending in the same cluster of cottages, the cemetery besides the track towards the sea and, beyond that, the machair in front of Sheigra’s sandy bay. And surrounding Sheigra, the wild windswept hillsides, lochans and rocky cliffs pounded by the Atlantic. (You can read reports on our 18 most recent Sheigra DXpeditions on the BDXC website here: http://bdxc.org.uk/articles.html ) Below: Sheigra from the north: Arkle and Ben Stack the mountains on the horizon. Once again we made Murdo’s traditional crofter’s cottage our DX base. From here our long wire Beverage aerials can radiate out across the hillsides towards the sea and the Americas to the west and north west, and eastwards towards Asia, parallel to the old, and now very rough, peat track which continues on north east into the open moors after the tarmac road ends at Sheigra. right: Dave earths the Caribbean Beverage. We were fortunate to experience good MW conditions throughout our fortnight’s stay, thanks to very low solar activity. And on the last couple of days we were treated to some superb conditions with AM signals from the -

Annual Report FY15: July 1, 2014–June 30, 2015

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC Annual Report Fiscal Year 2015 COA Development Office College of the Atlantic 105 Eden Street Bar Harbor, Maine 04609 Dean of Institutional Advancement Lynn Boulger 207-801-5620, [email protected] Development Associate Amanda Ruzicka Mogridge 207-801-5625, [email protected] Development Officer Kristina Swanson 207-801-5621, [email protected] Alumni Relations/Development Coordinator Dianne Clendaniel 207-801-5624, [email protected] Manager of Donor Engagement Jennifer Hughes 207-801-5622, [email protected] Every effort has been made to ensure accuracy in preparing all donor lists for this annual report. If a mistake has been made in your name, or if your name was omitted, we apologize. Please notify the development office at 207-801-5625 with any changes. www.coa.edu/support COA ANNUAL REPorT FY15: July 1, 2014–June 30, 2015 I love nothing more than telling stories of success and good news about our We love to highlight the achievements of our students, and one that stands out incredible college. One way I tell these stories is through a series I’ve created for from last year is the incredible academic recognition given to Ellie Oldach '15 our Board of Trustees called the College of the Atlantic Highlight Reel. A perusal of when she received a prestigious Fulbright Research Scholarship. It was the first the Reels from this year include the following elements: time in the history of the college that a student has won a Fulbright. Ellie is spending ten months on New Zealand’s South Island working to understand and COA received the 2014 Honor Award from Maine Preservation for our model coastal marsh and mussel bed communities. -

Bangor ^Cfjool

Bangor ^cfjool Jfortietij ^nnibersarp 19D7 - 1947 ‘ Bangor Hebrew Community Center October 2, 1947 AS THE TREE IS BENT, SO THE TREE SHALL GROW. --- PROVERBS FORTIETH ANNIVERSARY COMMEMORATION October the second Nineteen hundred and forty-seven 18 Tishri 5708 LISS MEMORIAL BUILDING BANGOR HEBREW SCHOOL Bangor, Maine 2 DEDICATION *> JJ N GRATEFUL RECOGNITION OF THEIR SACRIFICES AND COURAGEOUS DEVOTION TO THEIR COUNTRY, THESE FOR TIETH ANNIVERSARY EXERCISES AND THIS RECORD THERE OF ARE DEDICATED TO THE YOUTH OF OUR COMMUNITY WHO SERVED IN THE ARMED FORCES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA IN THE WAR WHICH BEGAN ON THE DAY OF INFAMY, DECEMBER 7, 1941, AND WAS VICTORI OUSLY CONCLUDED WITH THE SURRENDER OF JAPAN ON SEPTEMBER 2, 1945 .............................. HENRY H. SEGAL PRESIDENT 3 GUESTS OF HONOR Hon. Horace Hildreth Dr. Stephen S. Wise Governor of Maine Free Synagogue, New York Dr. Henry Knowlton Horace Estey Chairman City Council City Manager Dr. Harry Trust Roland Carpenter President Bangor Theological Seminary Superintendent of Schools Philip Lown James White President Maine Jewish Council Member Bangor City Council John O’Connell, Jr. Hendric Burns Bangor Daily News Bangor Daily Commercial Dr. Arthur Hauck Dr. Alexander Kohanski President University of Maine Executive Director, Maine Jewish Council Felix Ranlett Rev. T. Pappas Librarian Bangor Public Library Greek Orthodox Church HON. HORACE HILDRETH Governor State of Maine DR. STEPHEN S. WISE Rabbi Free Synagogue, New York City THE FORTIETH ANNIVERSARY COMMITTEE HENRY H. SEGAL GENERAL CHAIRMAN A. M. RUDMAN SIDNEY SCIIIRO SIHRLEY BERGER ABRAHAM STERN A. B. FRIEDMAN HARRY RABEN MYER SEGAL JOSEPH EMPLE LAWRENCE SLON MAX KOMINSKY MRS. -

Frank Morey Coffin's Political Years: Prelude to a Judgeship

Maine Law Review Volume 63 Number 2 Symposium:Remembering Judge Article 5 Frank M. Coffin: A Remarkable Legacy January 2011 Frank Morey Coffin's Political Years: Prelude to a Judgeship Donald E. Nicoll Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mainelaw.maine.edu/mlr Part of the Courts Commons, Judges Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Legislation Commons, and the Public Law and Legal Theory Commons Recommended Citation Donald E. Nicoll, Frank Morey Coffin's Political Years: Prelude to a Judgeship, 63 Me. L. Rev. 397 (2011). Available at: https://digitalcommons.mainelaw.maine.edu/mlr/vol63/iss2/5 This Article and Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Maine School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Maine School of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FRANK MOREY COFFIN’S POLITICAL YEARS: PRELUDE TO A JUDGESHIP Don Nicoll I. INTRODUCTION II. THE FIRST OF THREE BRANCHES III. UNFORESEEN CHANGES IV. INTO THE SECOND BRANCH V. TO THE THIRD BRANCH 398 MAINE LAW REVIEW [Vol. 63:2 FRANK MOREY COFFIN’S POLITICAL YEARS: PRELUDE TO A JUDGESHIP Don Nicoll* I. INTRODUCTION Each day when I go to my study, I see a wood block print of two owls gazing at me with unblinking eyes. Ever alert, they remind me of the artist, who in his neat, fine hand, titled the print “Deux Hiboux,” inscribed it to the recipients and signed it simply “FMC 8-2-87.” In addition to his talents as an artist and friend in all seasons, FMC was a remarkable public servant in all three branches of the federal government and, with his friend and colleague Edmund S. -

JOHN FOSTER DULLES PAPERS PERSONNEL SERIES The

JOHN FOSTER DULLES PAPERS PERSONNEL SERIES The Personnel Series, consisting of approximately 17,900 pages, is comprised of three subseries, an alphabetically arranged Chiefs of Mission Subseries, an alphabetically arranged Special Liaison Staff Subseries and a Chronological Subseries. The entire series focuses on appointments and evaluations of ambassadors and other foreign service personnel and consideration of political appointees for various posts. The series is an important source of information on the staffing of foreign service posts with African- Americans, Jews, women, and individuals representing various political constituencies. Frank assessments of the performances of many chiefs of mission are found here, especially in the Chiefs of Mission Subseries and much of the series reflects input sought and obtained by Secretary Dulles from his staff concerning the political suitability of ambassadors currently serving as well as numerous potential appointees. While the emphasis is on personalities and politics, information on U.S. relations with various foreign countries can be found in this series. The Chiefs of Mission Subseries totals approximately 1,800 pages and contains candid assessments of U.S. ambassadors to certain countries, lists of chiefs of missions and indications of which ones were to be changed, biographical data, materials re controversial individuals such as John Paton Davies, Julius Holmes, Wolf Ladejinsky, Jesse Locker, William D. Pawley, and others, memoranda regarding Leonard Hall and political patronage, procedures for selecting career and political candidates for positions, discussions of “most urgent problems” for ambassadorships in certain countries, consideration of African-American appointees, comments on certain individuals’ connections to Truman Administration, and lists of personnel in Secretary of State’s office. -

Annual Report FY16

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC Annual Report Fiscal Year 2016 COA BOARD OF TRUSTEES Timothy Bass Jay McNally '84 Ronald E. Beard Philip S.J. Moriarty Leslie C. Brewer Phyllis Anina Moriarty Alyne Cistone Lili Pew Lindsay Davies Hamilton Robinson, Jr. Beth Gardiner Nadia Rosenthal Amy Yeager Geier Abby Rowe ('98) H. Winston Holt IV Marthann Samek Jason W. Ingle Henry L.P. Schmelzer Philip B. Kunhardt III '77 Laura Z. Stone Nicholas Lapham Stephen Sullens Casey Mallinckrodt William N. Thorndike, Jr. Anthony Mazlish Cody van Heerden, MPhil '17 Linda McGillicuddy Life Trustees Trustee Emeriti Samuel M. Hamill, Jr. David Hackett Fischer John N. Kelly William G. Foulke, Jr. Susan Storey Lyman George B.E. Hambleton William V.P. Newlin Elizabeth Hodder John Reeves Sherry F. Huber Henry D. Sharpe, Jr. Helen Porter Cathy L. Ramsdell '78 John Wilmerding Every effort has been made to ensure accuracy in preparing this annual report. If a mistake has been made, or if your name was omitted, we apologize. Please notify the Dean of Institutional Advancement Lynn Boulger at 207-801-5620, or [email protected]. www.coa.edu/support COA FY16 ANNUAL REPORT (July 1, 2015–June 30, 2016) There are many analogies to describe the teaching, learning, and knowledge creation that goes on here at College of the Atlantic. The one I like best is building—we build a lot of things here. Some such building is actual, not analogous: there’s a fourth year student building a tiny house in the parking lot; another is rebuilding the battery terminals for our electric van; we just built a bed on wheels and placed third in the Bar Harbor Bed Races. -

Maine Alumnus, Volume 29, Number 4, January 1948

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine University of Maine Alumni Magazines University of Maine Publications 1-1948 Maine Alumnus, Volume 29, Number 4, January 1948 General Alumni Association, University of Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/alumni_magazines Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation General Alumni Association, University of Maine, "Maine Alumnus, Volume 29, Number 4, January 1948" (1948). University of Maine Alumni Magazines. 117. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/alumni_magazines/117 This publication is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Maine Alumni Magazines by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. After seeing the picture of sons and daughters of alumni in The Maine Alumnus a graduate wrote an inspiring letter to the Editor. His letter follows: ------------■, Mass. Mr Editor. The picture of alumni sons and daughters in The Alumnus arouses me more than anything that has come out of Maine in years. After I graduated from the University, the succeeding college generations did not interest me much. They seemed to be strangers in the halls that had been mine. They didn’t know me when I returned to them, and I did not know them. Perhaps I even felt resentful in a way that they had taken over what I considered mine. My loyalty to Maine may not have slipped, but my interest certainly has lagged. But these youngsters are the flesh and blood of my old gang and I am mighty glad that they have come back home. -

Maine State Legislature

MAINE STATE LEGISLATURE The following document is provided by the LAW AND LEGISLATIVE DIGITAL LIBRARY at the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library http://legislature.maine.gov/lawlib Reproduced from scanned originals with text recognition applied (searchable text may contain some errors and/or omissions) Public Documents of Mai11e: ANNUAL OF THE VARIO US I)UBLIC ffFFICERS AND INSTITUTIONS FOR THE YEAR 1883. VOLUME I. AUGUSTA: SP.H.A<:1-UE & SON, PRINTERS TO THE STATE. 1883. REGIS'rER OF THE ExecL1tive Depart1r1e11t OF THE STA TE OF MAINE, WITH RULES FOR THE GOVERNMENT THEREOF; ALSO CONTAINING THM Names of State and County Officers and Trustees and Officers of various State Institutions, For 1883-4. "AUGUSTA: SPRAGUE & SON. PRINTERS TO THE STATE. 1883. STATE OF MAINE. IN COUNCIL, January 10, 1883. ORDERED, That there be printed for the use of the Council, fifteen hundred copies of the Register of the Executive Department, with the rules for the government thereof. Attest: JOSEPH 0. SMITH, Secretary of State. ,-------------- ---~----------------------------------------~- --~--------------~-- State of Mai11e. EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT FOR 1883-4. GOVERNOR: FREDERICK ROBIE, GORHAM. COUNCILLORS : SILAS c. HATCH, BANGOH. JOSEPH A. LOCKE, PORTLAND. w. w. BOLSTER, AUBUltN. COLBY C. CORNISH, Wrnsww. JOHN P. SWASEY, CANTON. A. F. CROCKETT' ROCKLAND. NICHOLAS FESSENDEN' FT. FAIRFIELD. SECRETARY OF STATE: ,JOSEPH 0. SMITH, SKOWHEGAN, MESSENGER: CHARLES J. HOUSE, MONSON. STANDING CO:\fMITTEES OF THE EXECUTIVE COUNCIL FOR 1883-4. ------. ---~------ On lYarrants-1\Iessrs. HATCH, BoLSTEri, ConKisII. On Acconnts-1\iessrs. LOCKE, HATCH, CuoCKETT. On State Prison and Pa.rclons - Messrs. CORNISH, FESSENDEN, SWASEY. On Election Retu.rns-1\iessrs. -

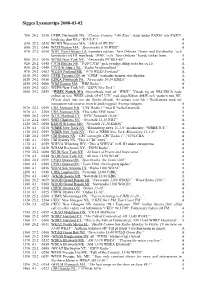

Sigges Lyssnartips 2008-03-02

Sigges Lyssnartips 2008-03-02 780 26.2 0326 CFDR Dartmouth NS, “Classic Country 7-80 Kixx”, både under PAX63 och PAX71 hörde jag dem ID:a “K-I-X-X”! A 830 25.2 0530 WCRN Worcester MA, “AM 8-30 WCRN”. A 850 25.2 0546 WEEI Boston MA, “Sportsradio 8-50 WEEI”. A 870 27.2 0558 WWL New Orleans LA, kanonbra reklam “New Orleans’ Home- and Gardenship” och kanonstört vid ID, men både “WWL” och “New Orleans” kunde värkas fram. A 880 25.2 0530 WCBS New York NY, “Newsradio WCBS 8-80”. A 920 26.2 0348 CJCH Halifax NS, “9-20 CJCH” gick ovanligt dåligt trots bra cx f.ö. A 930 25.2 0548 CJYQ St John’s NL, “Radio Newfoundland”. A 970 24.2 0503 WZAN Portland ME, “9-70 WZAN Portland”. A 1010 24.2 0605 CFRB Toronto ON, ett “CFRB” vaskades fram ur stör-oljuden. A 1020 24.2 0556 KDKA Pittsburgh PA, “Newsradio 10-20 KDKA”. A 1030 24.2 0606 WBZ Boston MA, “WBZ Radio”. A 1050 24.2 0621 WEPN New York NY, “ESPN New York”. A 1060 24.2 0559 --WBIX Natick MA, överraskade med ett “WBIX”. Visade sig att NRC/IRCA hade ordnat en test. WBIX sände 05-07 UTC med dageffekten 40kW och -pattern mot NE. (Visste dock inte om det förrän efteråt). Är annars svår här i Nordeuropa med sitt nattpattern rakt österut, men är ändå loggad i Sverige tidigare. A 1070 24.2 0559 CBA Moncton NB, “CBC Radio 1” med R Netherland-relä.