12.2% 130,000 155M Top 1% 154 5,300

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Handbook for Practicing the Original Reiki of Usui and Hay Pdf, Epub, Ebook

LIGHT ON THE ORIGINS OF REIKI: A HANDBOOK FOR PRACTICING THE ORIGINAL REIKI OF USUI AND HAY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tadao Yamaguchi | 195 pages | 01 Jan 2008 | LOTUS PRESS | 9780914955658 | English | Wisconsin, United States Light on the Origins of Reiki: A Handbook for Practicing the Original Reiki of Usui and Hay PDF Book Transcriptions Revised Romanization yeonggi. Read an excerpt of this book! Parapsychology Death and culture Parapsychology Scientific literacy. Adrenal fatigue Aerotoxic syndrome Candida hypersensitivity Chronic Lyme disease Electromagnetic hypersensitivity Heavy legs Leaky gut syndrome Multiple chemical sensitivity Wilson's temperature syndrome. Learn the basics, get attuned, and develop a solid self-care and meditation practice. Reiki is a Spiritual Discipline. Melissa Fotheringham rated it it was amazing Feb 10, Invest in Yourself. Four Faces is an adventurous survey of a universe that is deeper than science can measure. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. Reiki is a powerful healing energy. Level I and II required. None of these have any counterpart in the physical world. None of the studies in the review provided a rationale for the treatment duration and no study reported adverse effects. More filters. Jack Tips. By spreading the course over 8 or more lessons, you get the time to incorporate the Reiki energy into daily life. Members for A. Master Level. Pseudoscientific healing technique. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. The existence of qi has not been established by medical research. Kathia Munoz rated it really liked it Jan 28, You can learn Reiki so that you can become a conduit for helping others, or you can learn it for your own spiritual development. -

Testing the Rational of Candida Cleanse Diets

TESTING THE RATIONAL OF CANDIDA CLEANSE DIETS A thesis presented to the faculty of the Graduate School of Western Carolina University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Biology. By Sallie Katherine Lewis Director: Dr. Greg Adkison Biology Instructor Biology Department Committee Members: Dr. Sean O’Connell, Biology Dr. Sabine Rundle, Biology July 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee members and director for their assistance and encouragement; in particular, Dr. Greg Adkison for his incredible patience, Dr. Sabine Rundle for her constant reassurance, and Dr. Sean O’Connell for his kindness and consideration. In addition, I would like to recognize J Ryan Simmons for the time he spent proofreading and editing this document. I also extend my sincere thanks to my husband Eric Sheasby for his motivation and support. And lastly, I offer my deepest thanks to my family; my husband Eric Sheasby and my parents Mike and Sherrill Lewis. Thank you for always being my biggest cheerleaders. Without the support of all of the above mentioned people this thesis would not have been possible. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Figures .................................................................................................................... iv Abstract ................................................................................................................................v Introduction ..........................................................................................................................1 -

Chemical Exposures: Low Levels and High Stakes, Second Edition

Chemical Exposures Chemical Exposures Low Levels and High Stakes Second Edition Nicholas A. Ashford Claudia S. Miller JOHN WILEY & SONS, INC. NewYork • Chichester • Weinheim • Brisbane • Singapore • Toronto This text is printed on acid-free paper. Copyright © 1998 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. Published simultaneously in Canada. No part ofthis publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 and 108 ofthe 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission ofthe Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4744. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10158-0012. (212) 850-6011, fax (212) 850-6008, E-mail: [email protected]. Library ofCongress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ashford, Nicholas Askounes. Chemical exposures: low levels and high stakes / Nicholas A. Ashford & Claudia S. Miller - 2nd ed. p. em. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN 0-471-29240-0 I. Multiple chemical sensitivity. I. Miller, Claudia. II. Title. RB I52.6.A84 1997 615.9'02-dc21 97-19690 CIP 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 To my mother, Venette Askounes Ashford, from whom I learned to have compassion for those less fartunate than I, and who inspired me to help. -N.A.A. To my parents, Constance Lawrence Schultz. -

BCMJ -#51Vol6-July-09-July.Qxp

personal view limiting consumption of albacore 2 Letters for Personal View are welcomed. tuna. HealthLink BC and Health They should be double-spaced and few er Canada have set different serving than 300 words. The BCMJ reserves the limits and age categories in their fish right to edit letters for clarity and length. consumption recommendations. The Letters may be e-mailed (journal@bcma recommendations also differ some- .bc.ca), faxed (604 638-2917), or sent what from those of the State of through the post. Washington and the US FDA/EPA.3 One of my associates, Dr Laurie Chan, chair of Aboriginal environ- mental health at UNBC, has told me Flu protection for the accompanying document for “In - that cheaper light tuna tends to have fection Control Guidelines in Acute an Hg level 5 times lower than that physicians Care Facilities,” www.phac-aspc.gc found in albacore tuna.4 have recently moved from Ontario .ca/alert-alerte/swine-porcine/ I would sincerely like to know the to BC in rural family practice. I guidance-orientation-ipc-eng.php. background, rationale, and references Iwork in the clinic and hospital The BC Ministry of Health Ser- used by the Ministry of Health and the full-time in Invermere, BC. vices is not planning at this time to CDC to make this recommendation. I In Ontario every doctor’s office follow the Ontario decision to supply remember listening to Ray Copes in a was supplied with a stock of protective physicians’ private offices with pro- meeting one day, and he mentioned masks, gowns, etc., after the deaths of tective equipment as the ministry Continued on page 240 doctors, nurses, and paramedics in the believes it is properly the responsibil- SARS outbreak in Ontario. -

Reset the Yeast Connection

RESET THE YEAST CONNECTION Carolyn F. A. Dean MD ND Ver 2 ReSet The Yeast Connection www.RnAReSet.com TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Preview of Yeast ReSet Protocol SECTION ONE: ALL ABOUT YEAST Chapter One: The Personal Side of Yeast Chapter Two: Candida and its Toxic Friends Chapter Three: Show Me the Evidence Chapter Four: Making the Diagnosis SECTION TWO: YEAST BALANCE PROGRAM Chapter Five: Yeast ReSet Diet Chapter Six: Yeast ReSet Protocols Chapter Seven: Living a Yeast-Free Life SECTION THREE: TREATING CHILDREN, WOMEN AND MEN Chapter Eight: Children With Yeast Chapter Nine: Women With Yeast Chapter Ten: Men With Yeast SECTION FOUR: YEAST RESET MENU & RECIPES Chapter Eleven: Menu & Yeast ReSet Recipes REFERENCES MEET THE DOCTOR OF THE FUTURE Carolyn Dean MD ND 2 ReSet The Yeast Connection www.RnAReSet.com INTRODUCTION I’ve been studying health since my teens, and over the past five decades I’ve developed a very wide overview and perspective on our current health care crisis. Speaking with thousands of patients, clients, and callers on my radio show, I’ve identified two clear causes of most health problems. They are Mineral Deficiency and Yeast Overgrowth Syndrome (YOS) – and most people suffer from both. Candidiasis, Candida Related Complex, Candida Hypersensitivity, and Yeast Allergies are all names for what I call Yeast Overgrowth Syndrome, which I will shorten to YOS throughout the book. It’s a condition where yeast has overgrown and outgrown its natural environment in the large intestine and has invaded the small intestine. It is a health threat that remains untreated, mistreated, and if it’s ever recognized, it is undertreated. -

Idiopathic Environmental Intolerances 1999

Position Statement Idiopathic environmental intolerances AAAAI Board of Directors January 1999 AAAAI Position Statements and Work Group Reports are not to be considered to reflect current AAAAI standards or policy after five years from the date of publication. For reference only. The statement below is not to be construed as dictating an exclusive course of action nor is it intended to replace the medical judgment of healthcare professionals. The unique circumstances of individual patients and environments are to be taken into account in any diagnosis and treatment plan. The above statement reflects clinical and scientific advances as of the date of publication and is subject to change. 1-3 Abbreviations used: The condition now called idiopathic environmental intolerances (IEI) 4 IEI: Idiopathic environmental and formerly known as multiple chemical sensitivities (MCS) or intolerances environmental illness was addressed in the AAAI Position Statement on 5 MCS: Multiple chemical Clinical Ecology published in 1986. Since then, additional research and sensitivities clinical studies have been reported. This updated position by the AAAAI reflects the current status of this condition as documented in the published scientific literature. Definition and Terminology The term environmental illness was used for many years to refer to a subjective illness in certain persons who typically describe multiple symptoms, which they attribute to numerous and varied environmental chemical exposures, in the absence of objective diagnostic physical findings or laboratory test abnormalities that define an illness. Other terms, such as universal allergy, 20th-century disease, chemical hypersensitivity syndrome, total allergy syndrome, and cerebral allergy have also been used to describe the same condition. -

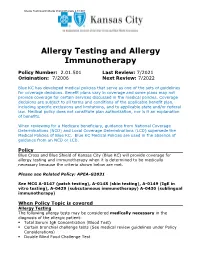

Allergy Testing and Allergy Immunotherapy 2.01.501

Allergy Testing and Allergy Immunotherapy 2.01.501 Allergy Testing and Allergy Immunotherapy Policy Number: 2.01.501 Last Review: 7/2021 Origination: 7/2006 Next Review: 7/2022 Blue KC has developed medical policies that serve as one of the sets of guidelines for coverage decisions. Benefit plans vary in coverage and some plans may not provide coverage for certain services discussed in the medical policies. Coverage decisions are subject to all terms and conditions of the applicable benefit plan, including specific exclusions and limitations, and to applicable state and/or federal law. Medical policy does not constitute plan authorization, nor is it an explanation of benefits. When reviewing for a Medicare beneficiary, guidance from National Coverage Determinations (NCD) and Local Coverage Determinations (LCD) supersede the Medical Policies of Blue KC. Blue KC Medical Policies are used in the absence of guidance from an NCD or LCD. Policy Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kansas City (Blue KC) will provide coverage for allergy testing and immunotherapy when it is determined to be medically necessary because the criteria shown below are met. Please see Related Policy: APEA-G2031 See MCG A-0147 (patch testing), A-0148 (skin testing), A-0149 (IgE in vitro testing), A-0429 (subcutaneous immunotherapy) A-0430 (sublingual immunotherapy) When Policy Topic is covered Allergy Testing The following allergy tests may be considered medically necessary in the diagnosis of the allergic patient: . Total Serum IgE Concentration (Blood Test) . Certain bronchial challenge tests (See medical review guidelines under Policy Considerations) . Double Blind Food Challenge Test Allergy Testing and Allergy Immunotherapy 2.01.501 When Policy Topic is not covered Allergy tests considered investigational in the diagnosis of the allergic patient include, but are not limited to: . -

Microorganisms

microorganisms Review Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: An Immunological Perspective Diletta Rosati 1 , Mariolina Bruno 1 , Martin Jaeger 1, Jaap ten Oever 1 and Mihai G. Netea 1,2,* 1 Department of Internal Medicine and Radboud Center for Infectious Diseases, Radboud University Medical Center, 6525 GA Nijmegen, The Netherlands; [email protected] (D.R.); [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (M.J.); [email protected] (J.t.O.) 2 Department for Genomics & Immunoregulation, Life and Medical Sciences Institute (LIMES), University of Bonn, 53115 Bonn, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 19 December 2019; Accepted: 17 January 2020; Published: 21 January 2020 Abstract: Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) is a widespread vaginal infection primarily caused by Candida albicans. VVC affects up to 75% of women of childbearing age once in their life, and up to 9% of women in different populations experience more than three episodes per year, which is defined as recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC). RVVC results in diminished quality of life as well as increased associated healthcare costs. For a long time, VVC has been considered the outcome of inadequate host defenses against Candida colonization, as in the case of primary immunodeficiencies associated with persistent fungal infections and insufficient clearance. Intensive research in recent decades has led to a new hypothesis that points toward a local mucosal overreaction of the immune system rather than a defective host response to Candida colonization. This review provides an overview of the current understanding of the host immune response in VVC pathogenesis and suggests that a tightly regulated fungus–host–microbiota interplay might exert a protective role against recurrent Candida infections. -

Frans Vermeulen Kingdom Fungi

Frans Vermeulen Kingdom Fungi - Spectrum Materia Medica Volume 2 Reading excerpt Kingdom Fungi - Spectrum Materia Medica Volume 2 of Frans Vermeulen Publisher: Emryss Publisher http://www.narayana-verlag.com/b3339 In the Narayana webshop you can find all english books on homeopathy, alternative medicine and a healthy life. Copying excerpts is not permitted. Narayana Verlag GmbH, Blumenplatz 2, D-79400 Kandern, Germany Tel. +49 7626 9749 700 Email [email protected] http://www.narayana-verlag.com Contents Introduction xxix Fungi and fungal diseases xxix Fungal remedies xxx Keys xxxi Enigmatic species xxxi Believing is Seeing xxxiii Acknowledgements xxxiii Classification Kingdom Fungi xxxiv - xlvii Fungal taxonomy xlvii Biology of Fungi xlviii Differences with plants xlviii Expansion and penetration xlix Reproduction l Spores lii Metabolism lii Light liv Growing conditions lv Rapidity lv Fungal frigidity lv Constant activity to maintain intimate relationship with environment lvi Relationship to immediate environment – settling down lvii Strength and survival lix Flexibility lxi Colonizers lxiii Food and alcohol lxv Alcohol and urine lxvi Pharmaceuticals lxvii Nutritional value lxvii Fungophobia lxviii Fungophobal prose and poetry lxx Embodiment of bad properties lxxii Fungal lore lxxiii Fungophilia lxxv Mushrooms of immortality lxxvi Sacred mushrooms lxxvii India lxxvii Crossing bridges lxxviii Mediators lxxx Dangers of fungi lxxx Antidotes lxxxiii Nothing ventured, nothing gained lxxxiv Like a child lxxxv Mycotoxins lxxxviii Fungal -

PDF Download the Bach Flower Remedies

THE BACH FLOWER REMEDIES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Edward Bach,F. J. Wheeler | 192 pages | 01 Nov 1998 | Keats Pub Inc | 9780879838690 | English | New Canaan, CT, United States The Bach Flower Remedies PDF Book They often take alcohol or drugs in excess, to stimulate them and help themselves bear their trials with cheerfulness. Conclusion Our review demonstrates that the currently available evidence indicates that BFRs are not more efficacious than a placebo intervention for psychological problems but are probably safe. GG participated in the design of the review, gave methodological advice, and edited the manuscript. Three placebo-controlled RCTs examined the efficacy of BFRs for the treatment of examination anxiety in students between the ages of 18 and Acad Med. Preparations list Regulation and prevalence Homeopathy and allopathy Homeoprophylaxis Quackery. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Harms Of the four controlled trials, one did not make any reference to harms of BFRs. For efficacy, we included all prospective studies with a control group. Allow Disallow. Find the perfect partner for your busy lifestyle here. They are strong of will and have much courage when they are convinced of those things that they wish to teach. In illness they struggle on long after many would have given up their duties. These vague inexplicable fears may haunt by night or day. For this reason we included evidence from controlled trials as well as observational studies. Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Vohra Our Products. Efficacy of BFRs for examination anxiety Three placebo-controlled RCTs examined the efficacy of BFRs for the treatment of examination anxiety in students between the ages of 18 and Our analysis of the four controlled trials of BFRs for examination anxiety and ADHD indicates that there is no evidence of benefit compared with a placebo intervention. -

Yeasts in the Gut: from Commensals to Infectious Agents Jürgen Schulze, Ulrich Sonnenborn

MEDICINE REVIEW ARTICLE Yeasts in the Gut: From Commensals to Infectious Agents Jürgen Schulze, Ulrich Sonnenborn SUMMARY hree decades ago, on the basis of case reports, the American physician C. O. Truss (e1–e3) Background: Controversy still surrounds the question T proposed the hypothesis that an unhealthy lifestyle whether yeasts found in the gut are causally related to and increased intake of drugs, modified foods, and disease, constitute a health hazard, or require treatment. pollutants could lead to overgrowth of Candida Methods: The authors present the state of knowledge in this species in the intestine. This would generally reduce area on the basis of a selective review of articles retrieved the defenses of the host organism and trigger a multi- by a PubMed search from 2005 onward. The therapeutic organ Candida-associated complex of symptoms recommendations follow the current na tional and (“Candida hypersensitivity syndrome”). Since then, international guidelines. this topic has been repeatedly and vigorously dis- Results: Yeasts, mainly Candida species, are present in the cussed by experts and laymen. In 1996, C. Seebacher gut of about 70% of healthy adults. Mucocutaneous Candida even claimed that “mycophobia” was spreading. infections are due either to impaired host defenses or to Many of the publications supporting Truss’s hypoth- altered gene expression in formerly commensal strains. esis are not to be taken seriously. Abnormal condi- The expression of virulence factors enables yeasts to form tions and severe diseases have often been uncritically biofilms, destroy tissues, and escape the immunological linked to the mere detection of fungi in the gut, lead- attacks of the host. -

Text Atlas of Nail Disorders

A Text Atlas of Nail Disorders Techniques in Investigation and Diagnosis Third edition Robert Baran, MD Nail Disease Centre Cannes, France Rodney PR Dawber, MA, MB ChB, FRCP Consultant Dermatologist Churchill Hospital, Oxford, UK Eckart Haneke, MD Klinikk Bunaes Sandvika/Oslo, Norway Antonella Tosti, MD Associate Professor of Dermatology, University of Bologna Bologna, Italy Ivan Bristow, MSc, BSc, DPodM, MChS Podiatrist, University College of Northampton Northampton, UK With contributions from Luc Thomas, MD, PhD Professor of Dermatology, University of Lyon, France Jean-Luc Drapé, MD, PhD Professor of Radiology, Hôpital Cochin, University of Paris Paris, France LONDON AND NEW YORK © 1990, 1996, 2003, Martin Dunitz, a member of the Taylor & Francis Group First published in the United Kingdom in 1990 by Martin Dunitz, Taylor & Francis Group plc, 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Tel: +44 (0) 20 7583 9855 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7842 2298 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.dunitz.co.uk This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge's collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” Third edition 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 0LP.