Chapter Four

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Physics Group Newsletter No 21 January 2007

History of Physics Group Newsletter No 21 January 2007 Cover picture: Ludwig Boltzmann’s ‘Bicykel’ – a piece of apparatus designed by Boltzmann to demonstrate the effect of one electric circuit on another. This, and the picture of Boltzmann on page 27, are both reproduced by kind permission of Dr Wolfgang Kerber of the Österreichische Zentralbibliothek für Physik, Vienna. Contents Editorial 2 Group meetings AGM Report 3 AGM Lecture programme: ‘Life with Bragg’ by John Nye 6 ‘George Francis Fitzgerald (1851-1901) - Scientific Saint?’ by Denis Weaire 9 ‘Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) - a brief biography by Peter Ford 15 Reports Oxford visit 24 EPS History of physics group meeting, Graz, Austria 27 European Society for the History of Science - 2nd International conference 30 Sir Joseph Rotblat conference, Liverpool 35 Features: ‘Did Einstein visit Bratislava or not?’ by Juraj Sebesta 39 ‘Wadham College, Oxford and the Experimental Tradition’ by Allan Chapman 44 Book reviews JD Bernal – The Sage of Science 54 Harwell – The Enigma Revealed 59 Web report 62 News 64 Next Group meeting 65 Committee and contacts 68 2 Editorial Browsing through a copy of the group’s ‘aims and objectives’, I notice that part of its aims are ‘to secure the written, oral and instrumental record of British physics and to foster a greater awareness concerning the history of physics among physicists’ and I think that over the years much has been achieved by the group in tackling this not inconsiderable challenge. One must remember, however, that the situation at the time this was written was very different from now. -

Thomas Willis and the Fevers Literature of the Seventeenth Century

Medical History, Supplement No. 1, 1981: 45-70 THOMAS WILLIS AND THE FEVERS LITERATURE OF THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY by DON G. BATES* WE NEED not take literally the "common Adagy Nemo sine febri moritur," even for seventeenth-century England.' Nor is it likely that Fevers put "a period to the lives of most men".2 Nevertheless, the prevalence and importance of this "sad, comfortless, truculent disease" in those times cannot be doubted. Thomas Willis thought that Fevers had accounted for about a third of the deaths of mankind up to his day, and his contemporary and compatriot, if not his friend, Thomas Sydenham, guessed that two- thirds of deaths which were not due to violence were the result of that "army of pestiferous diseases", Fevers.3 These estimates are, of course, based almost entirely on impressions.4 But such impressions form the subject of this paper, for it is the contemporary Fevers literature upon which I wish to focus attention, the literature covering little more than a century following the death of the influential Jean Fernel in 1558. In what follows, I shall poke around in, rather than survey, the site in which this literature rests, trying to stake out, however disjointedly and incompletely, something of the intellectual, social, and natural setting in which it was produced. In keeping with the spirit of this volume, this is no more than an exploratory essay of a vast territory and, even so, to make it manageable, I have restricted myself largely to *Don G. Bates, M.D., Ph.D., Department of Humanities and Social Studies in Medicine. -

Willis and the Virtuosi

Forum on Public Policy The Scientific Method through the Lens of Neuroscience; From Willis to Broad J. Lanier Burns, Professor, Research Professor of Theological Studies, Senior Professor of Systematic Theology, Dallas Theological Seminar Abstract: In an age of unprecedented scientific achievement, I argue that the neurosciences are poised to transform our perceptions about life on earth, and that collaboration is needed to exploit a vast body of knowledge for humanity’s benefit. The scientific method distinguishes science from the humanities and religion. It has evolved into a professional, specialized culture with a common language that has synthesized technological forces into an incomparable era in terms of power and potential to address persistent problems of life on earth. When Willis of Oxford initiated modern experimentation, ecclesial authorities held intellectuals accountable to traditional canons of belief. In our secularized age, science has ascended to dominance with its contributions to progress in virtually every field. I will develop this transition in three parts. First, modern experimentation on the brain emerged with Thomas Willis in the 17th Century. A conscientious Anglican, he postulated a “corporeal soul,” so that he could pursue cranial research. He belonged to a gifted circle of scientifically minded scholars, the Virtuosi, who assisted him with his Cerebri anatome. He coined a number of neurological terms, moved research from the traditional humoral theory to a structural emphasis, and has been remembered for the arterial structure at the base of the brain, the “Circle of Willis.” Second, the scientific method is briefly described as a foundation for understanding its development in neuroscience. -

Library Exhibition

LIBRARY EXHIBITION DRAMATIS PERSONAE William Cole (1635-1716): Physician in Henry Sampson (1629-1700): Historian of the Worcester. Author of a treatise on the se- dissenters and physician to non- cretions of animals. conformists in London. Contributor to the Sir John Floyer (1649-1734): Physician in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. Lichfield. Author of works on asthma, John Wilkins (1614-1672): A cadaver. Once therapeutic bathing, and enthusiast for tak- Bishop of Chester. Founder member of the ing a patient’s pulse. Royal Society. Popularizer of Galileo. Crea- Richard Higgs (ca. 1632-1690): A physician in tor of a universal language. Coventry. Supplier to the pesthouse there. Thomas Willis (1621-1675): Physician in Ox- Richard Lower (1631-1691): Physician in ford. Associate of Messrs Boyle, Wren, London. Author of a major work on the Locke, Hooke. Writer of pioneering work heart and circulatory system, performed the on the brain. Sedleian Professor of Natural first successful blood-transfusion on two Philosophy at Oxford. dogs. Walter Needham (1631?-1691?): Anatomical lecturer to the Company of Surgeons. Au- thor of a work on foetal anatomy. The Medical Correspondence of Richard Higgs Gathered together in a single album kept here in the Library are a selection of letters from numerous key figures of the late 17th century flowering of scientific and medical thought and discovery that took place in Oxford. All of these letters are addressed to Dr Richard Higgs, and yet, for an associate of such illustrious figures, Higgs himself is elusive in the historical record. Originally from Gloucestershire, he appears to have matriculated at Queen’s College in Oxford in 1642 at around the age of 17, before embarking on medical training at Hart Hall, to graduate DM in 1659. -

Dr. Thomas Willis and His 'Circle' in the Brain

Historical Vignette Nepal Journal of Neuroscience 2:77-79, 2005 Dr. Thomas Willis and his ‘Circle’ in the Brain PVS Rana, MD, DM Department of Medicine With the advances in microneurosurgery and the ability to tackle (Neurology) diseases of the intracranial arteries at the base of the brain (often Manipal Teaching Hospital referred to as the Circle of Willis) surgically more effectively, accurate Manipal College of Medical Sciences knowledge of the intracranial vascular anatomy is increasingly Pokhara, Nepal important. Although Dr. Thomas Willis is best remembered for the Address for correspondence: accurate description of arterial anastomosis at the baseof the brain, PVS Rana, MD, DM his contribution to neuroanatomy, physiology and medical science in Department of Medicine general is vast, and several diseases bear his name. In this article an (Neurology) attempt has been made to review the life of Dr. Willis followed by a Manipal Teaching Hospital short description of the “Circle of Willis.” manipal College of Medical Sciences Pokhara, Nepal Key Words: anatomy, Circle of Willis, Dr. Thomas Willis Email: [email protected] Received, December 18, 2004 Accepted, December 30, 2004 “Anne Green was a 22- year-old woman who had been employed as a housemaid by Sir Thomas Read in Oxfordshire. She was probably seduced by his grandson, who turned her down when she became pregnant. The unlucky girl gave birth to a premature child whom she concealed. The dead boy was found, however, and Anne Green was accused of the murder of her own child. She was sentenced to die by hanging and the execution took place on December 14, 1650. -

Thomas Willis

NeuroQuantology 2005|Issue 4|Page 296-297 296 NQ-Biography, Thomas Willis NQ-Biography Thomas Willis Thomas Willis (1621-1673) was an English physician who played an important part in the history of the science of anatomy, was a co-founder of the Royal Society (1662) and is often considered the 'father of neurology'. Willis worked as a physician in Westminster, London, and from 1660 until his death was Sedleian Professor of Natural Philosophy at Oxford. He was a pioneer in research into the anatomy of the brain, nervous system and muscles. The "circle of Willis", a part of the brain's vascular system, was his discovery. His anatomy of the brain and nerves, as described in his Cerebri anatomi of 1664, is so minute and elaborate, and abounds so much in new information, that it presents an enormous contrast with the vague and meagre efforts of his predecessors. This work was not the result of his own personal and unaided exertions; he acknowledged his debt to Sir Christopher Wren and Thomas Millington, and his fellow-anatomist Richard Lower. Wren was the illustrator of the magnificent figures in the book. Willis was the first natural philosopher to use the term "reflex action" to describe elemental acts of the nervous system. He also wrote Pathologiae Cerebri et Nervosi Generis Specimen, 1667 (An Essay of the Pathology of the Brain and Nervous Stock) and of De Anima Brutorum, 1672 (Discourses Concerning the Souls of Brutes). Willis was the first to number the cranial nerves in the order in which they are now usually enumerated by anatomists. -

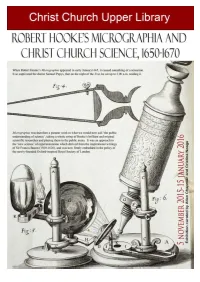

Robert Hooke's Micrographia

Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 is curated by Allan Chapman and Cristina Neagu, and will be open from 5 November 2015 to 15 January 2016. An exhibition to mark the 350th anniversary of the publication of Robert Hooke's Micrographia, the first book of microscopy. The event is organized at Christ Church, where Hooke was an undergraduate from 1653 to 1658, and includes a lecture (on Monday 30 November at 5:15 pm in the Upper Library) by the science historian Professor Allan Chapman. Visiting hours: Monday: 2.00 pm - 4.30 pm; Tuesday - Thursday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm; 2.00 pm - 4.00 pm; Friday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm Article on Robert Hooke and Early science at Christ Church by Allan Chapman Scientific equipment on loan from Allan Chapman Photography Alina Nachescu Exhibition catalogue and poster by Cristina Neagu Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Early Science at Christ Church, 1660-1670 Micrographia, Scheme 11, detail of cells in cork. Contents Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 Exhibition Catalogue Exhibits and Captions Title-page of the first edition of Micrographia, published in 1665. Robert Hooke’s Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 When Robert Hooke’s Micrographia: or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses with Observations and Inquiries thereupon appeared in early January 1665, it caused something of a sensation. It so captivated the diarist Samuel Pepys, that on the night of the 21st, he sat up to 2.00 a.m. -

![ON THOMAS WILLIS's CONCEPTS of NEUROPHYSIOLOGY [Part I] by ALFRED MEYER and RAYMOND HIERONS I](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8172/on-thomas-williss-concepts-of-neurophysiology-part-i-by-alfred-meyer-and-raymond-hierons-i-2918172.webp)

ON THOMAS WILLIS's CONCEPTS of NEUROPHYSIOLOGY [Part I] by ALFRED MEYER and RAYMOND HIERONS I

ON THOMAS WILLIS'S CONCEPTS OF NEUROPHYSIOLOGY [Part I] by ALFRED MEYER AND RAYMOND HIERONS I. INTRODUCTION IN previous papers we have dealt with problems of priority in relation to the circle of Willis* and the cranial nerves.1,2 We now turn to Willis's neuro- physiological concepts and his endeavours to localize nervous and mental functions. Willis dealt with these problems not only in Cerebri Anatome (I664), but also in later works, particularly De Morbis Convulsivis (I667) and De Anima Brutorum (I672). It is essential to draw from all his work, since his views were modified or amplified in his later publications. Of De Anima the second (pathological) discourse has been widely acknowledged (its importance has been extolled by Calmeil4 and Vinchon and Vie5), but the first part has-on the whole- attracted less attention. This may be because neither on the neurophysiological nor on the psychological level did Willis make any major new contribution. The anatomical description of the brain seldom goes beyond that in Cerebri Anatome. Chapter 3, which contains valuable descriptions of the comparative anatomy of the oyster, lobster and earthworm," was written primarily in order to explain the respiration ofanimals living in water or buried in earth. Thomas Hobbes, Locke, Berkeley, Hume and David Hartley were the chief architects of empirical psychology in England: none appears to have been appreciably influenced by Willis's writings, with the exception of Berkeley who, in Sins,7 only referred to Willis's notion ofthe kindling ofthe blood when he discussed the remedial properties of tar water. Charleton, in The Diferent Wits of Men,8 gives a more readable and more interesting account of the psychological (and some psychopathological) aspects. -

Thomas Willis, the Restoration and the First Works of Neurology

Med. Hist. (2015), vol. 59(4), pp. 525–553. c The Author 2015. Published by Cambridge University Press 2015 doi:10.1017/mdh.2015.45 Thomas Willis, the Restoration and the First Works of Neurology LOUIS CARON* Independent Scholar, 4675 Via Huerto, Santa Barbara, CA 93110, USA Abstract: This article provides a new consideration of how Thomas Willis (1621–75) came to write the first works of ‘neurology’, which was in its time a novel use of cerebral and neural anatomy to defend philosophical claims about the mind. Willis’s neurology was shaped by the immediate political and religious contexts of the English Civil War and Restoration. Accordingly, the majority of this paper is devoted to uncovering the political necessities Willis faced during the Restoration of the English monarchy in 1660, with particular focus on the significance of Willis’s dedication of his neurology and natural philosophy to the Archbishop of Canterbury, Gilbert Sheldon. Because the Restoration of Charles II brought only a semblance of order and peace, Willis and his allies understood the need for a coherent defense of the authority of the English church and its liturgy. Of particular importance to Sheldon and Willis (and to others in Sheldon’s circle) were the specific ceremonies described in the Book of Common Prayer, a manual that directed the congregation to assume various postures during public worship. This article demonstrates that Willis’s neurology should be read as an intervention in these debates, that his neurology would have been read at the time as an attempt to ground orthodox worship in the structure of the brain and nerves. -

Sir Roger Penrose Wins Nobel Prize

The Oxford Mathematics Annual Newsletter 2021 Sir Roger Penrose wins Nobel Prize Oxford Mathematics and the coronavirus Ideas for a complex world Equality, diversity and inclusion Can maths help us to win at Fantasy Football? Ideas for a Head of Department’s letter 3 Contents complex world 7 Interview with Jon Keating 9 Ulrike Tillmann, Fernando Alday, Bryan Birch 11 Appointments and achievements 15 The past year in Oxford Mathematics 17 Oxford Mathematics Obituary: Peter M. Neumann OBE 18 in the time of the coronavirus A world history of mathematics 21 12 Sir Roger Penrose wins Nobel Prize What’s on in Oxford Mathematics? 5 400 years of the Sedleian Professors 22 Equality, diversity and inclusion in New books by Oxford Mathematicians 24 Oxford Mathematics 20 Helping future students Undergraduate lectures for the world 25 Social media #WhatsonYourMind Can maths help us to win at Fantasy Football? Public Lectures 26 23 Our Graduate Student Campaign A final thought 27 2 Oxford Mathematics Annual Newsletter 2021 I am writing this in early 2021, and like everyone concerned about how that would work in practice, else I am hoping this will be a better year than but our students at home coped amazingly well 2020. The coronavirus pandemic has been an with the challenges of using their mobile phones to enormous challenge for all of us. With the benefit of photograph and upload their examination scripts, hindsight, there are definitely some things I would and surprisingly few had major internet problems. have done differently over the past 10 months. -

The Bio-Medical Pursuits of Christopher Wren*

THE BIO-MEDICAL PURSUITS OF CHRISTOPHER WREN* by WILLIAM CARLETON GIBSON IN A YEAR characterized by men walking about on the moon, some will ask why we should concern ourselves with the exploits of a great architect, once a geometer and mathematician, an astronomer, the father of blood transfusion and above all-a great public servant. My answer is simply that in the commemoration of another great citizen-scientist, Dr. Sydney Monckton Copeman, a physician with universal interests, nothing is more fitting than a recital of those parts of Christopher Wren's career which betray a life-long interest in biology and medicine, too often overlooked by his admirers. Nor is this year of men landing on the moon foreign to the interests of our good Christopher Wren, for he was a child of six years, at Windsor, when in 1638 his friend and mentor there, the Reverend John Wilkins published his famous Discovery ofa World in the Moon. After discussing such problems as a 'motive faculty to over- come gravity', and 'the cold rarified atmosphere', Wilkins says, so prophetically: 'Tis likely enough that there may be a means invented of journying to the Moone; And how happy shall they be, that are first successful in this attempt' (See fig. 3). It is no accident therefore, that when Wren, as an Oxford undergraduate, came under the tutelage of Warden Wilkins at Wadham College, they should combine forces to produce a telescope eighty feet long, as they said, 'to see at once the whole moon'. Nor do we find it strange that the youthful Wren should produce the first lunar globe in history-now lost to science, alas. -

EEG in Connection with Coma 53 – 7

Feature Neurophysiology REVIEW ARTICLE Feature Neurophysiology Review article EEG in connection with coma 53 – 7 BACKGROUND Coma is a dynamic condition that may have various causes. Important chan- John A. Wilson ges may take place rapidly, often with implications for treatment. The purpose of this article [email protected] Section for Clinical Neurophysiology is to provide a brief overview of EEG patterns for comas with various causes, and indicate how EEG can contribute to an assessment of the prognosis for coma patients. Helge J. Nordal Department of Neurology METHOD The article is based on many years of clinical and research experience with EEG Oslo University Hospital in connection with coma states. A self-built reference database was supplemented with searches in PubMed for relevant articles. RESULTS EEG reveals immediate changes in coma, and can provide early information on cause and prognosis. It is the only diagnostic tool for detecting non-convulsive epileptic MAIN POINTS status. Locked-in syndrome may be overlooked without EEG. Repeated EEG recordings EEG holds a central place in the assessment increase diagnostic certainty and make it possible to monitor coma developments. and treatment of coma INTERPRETATION EEG reflects brain function continuously and therefore holds a key place Repeated EEG recordings may be useful in in the assessment and treatment of coma. connection with coma irrespective of cause Some causes and complications of coma The word «coma» stems from Greek, and standing of electroencephalography (EEG), can only be diagnosed with the aid of EEG means deep sleep. The term is first found in with an outline of the basic physiology and the works of Hippocrates (ca.