Securitas Im Perii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trials of the War Criminals

TRIALS OF THE WAR CRIMINALS General Considerations The Fascist regime that ruled Romania between September 14, 1940, and August 23, 1944, was brought to justice in Bucharest in May 1946, and after a short trial, its principal leaders—Ion and Mihai Antonescu and two of their closest assistants—were executed, while others were sentenced to life imprisonment or long terms of detention. At that time, the trial’s verdicts seemed inevitable, as they indeed do today, derived inexorably from the defendants’ decisions and actions. The People’s Tribunals functioned for a short time only. They were disbanded on June 28, 1946,1 although some of the sentences were not pronounced until sometime later. Some 2,700 cases of suspected war criminals were examined by a commission formed of “public prosecutors,”2 but only in about half of the examined cases did the commission find sufficient evidence to prosecute, and only 668 were sentenced, many in absentia.3 There were two tribunals, one in Bucharest and one in Cluj. It is worth mentioning that the Bucharest tribunal sentenced only 187 people.4 The rest were sentenced by the tribunal in Cluj. One must also note that, in general, harsher sentences were pronounced by the Cluj tribunal (set up on June 22, 1 Marcel-Dumitru Ciucă, “Introducere” in Procesul maresalului Antonescu (Bucharest: Saeculum and Europa Nova, 1995-98), vol. 1: p. 33. 2 The public prosecutors were named by communist Minister of Justice Lucret iu Pătrăşcanu and most, if not all of them were loyal party members, some of whom were also Jews. -

Clark, Roland. "Reaction." Sectarianism and Renewal in 1920S Romania: the Limits of Orthodoxy and Nation-Building

Clark, Roland. "Reaction." Sectarianism and Renewal in 1920s Romania: The Limits of Orthodoxy and Nation-Building. London,: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021. 77–85. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 24 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350100985.ch-004>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 24 September 2021, 21:07 UTC. Copyright © Roland Clark 2021. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 4 Reaction The process of unifying four different churches into a single patriarchate understandably caused some people to worry that something was being lost in the process. Tensions between metropolitans and bishops reflected dissatisfaction among parish clergy and laypeople as well, which in some cases resulted in the formation of new religious movements. As a society experiencing extraordinary social and political upheavals, including new borders, a nationalizing state, industrialization, new communication and transportation networks and new political ideologies, inter-war Romania was a fecund environment for religious innovation. With monasticism in decline and ever higher expectations being placed on both priests and laypeople, two of the most significant new religious movements of the period emerged in regions where monasticism and the monastic approach to spirituality had been strongest. The first, Inochentism, began in Bessarabia just before the First World War. Its apocalyptic belief that the end times were near included a strong criticism of the Church and the state, a critique that transferred smoothly onto the Romanian state and Orthodox Church once the region became part of Greater Romania. -

Joint Submission of the Promo-Lex Association and Anti-Discrimination Centre Memorial

JOINT SUBMISSION OF THE PROMO-LEX ASSOCIATION AND ANTI-DISCRIMINATION CENTRE MEMORIAL Information submitted to the 62 Session (18 Sep 2017 - 06 Oct 2017) of the Committee on the Economic, Social and Cultural Rights August 2017 Promo-LEX Association is a non-governmental organization that aims to advance democracy in the Republic of Moldova, including in the Transnistrian region, by promoting and defending human rights, monitoring the democratic processes, and strengthening civil society through a strategic mix of legal action, advocacy, research and capacity building. Anti-Discrimination Centre Memorial works on protection of the rights of discriminated minorities and vulnerable groups in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, carrying out monitoring, reporting, advocacy on local and international level, human rights education. CONTACTS DUMITRU SLIUSARENCO STEPHANIA Kulaeva Promo-LEX Association ADC Memorial [email protected] [email protected] Of. Bd. Stefan cel Mare 127, Chisinau, R. Moldova ADC Memorial, Mundo B, rue d’Edimbourg, 1050 Brussels, Belgium 0 CONTENTS CHAPTER I. WOMEN’S RIGHT TO WORK ................................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 1 LEGAL FRAMEWORK ............................................................................................................................... 2 DISCRIMINATORY LEGAL PROVISIONS ................................................................................................ -

Feasibility Study for Railway Infrastructure Need Assessment in Moldova – Environmental and Social Appraisal Task 4

Moldovan Railway Restructuring project 24/11/2017 FEASIBILITY STUDY FOR RAILWAY INFRASTRUCTURE NEED ASSESSMENT IN MOLDOVA – ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL APPRAISAL TASK 4 REF: EME – FR01T16G53-11 MOLDOVAN RAILWAY RESTRUCTURING PROJECT FEASIBILITY STUDY FOR RAILWAY INFRASTRUCTURE NEED ASSESSMENT IN MOLDOVA – ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL APPRAISAL TASK 4 FICHE D’IDENTIFICATION Client CFM (Calea Ferata Din Moldova) Project Moldovan Railway Restructuring project Feasibility study for Railway infrastructure need assessment in Study Moldova – Environmental and Social Appraisal Task 4 Document Environmental and Social Appraisal Date 24/11/2017 Nom du fichier Feasibility study Moldova - Inception report - Frame Reference CFM Feasibility Study ToR - ENG Référence EME – FR01T16G53-11 Confidentiality Yes Language English Number of pages 128 APPROVAL Version Name Position Date Visa Modifications Environmental KRAJCOVIC Roman 24/11/2017 expert 6 GAUDRY Alain Key expert 24/11/2017 CUDENNEC Hervé EME Region 24/11/2017 SYSTRA • société anonyme à directoire et conseil de surveillance CS 41594 • 72,rue Henry Farman • 75513 Paris Cedex 15 • France | Tel +33 1 40 16 61 00 • Fax +33 1 40 16 61 04 Capital social 27 283 102 Euros | RCS Paris 387 949 530 | APE 7112B | TVA intra FR19387949530 4. LEGAL REQUIREMENTS The Environmental and Social Impact Assessment process is mainly based on and guided by the following documents: The Moldovan legislation on the Environmental Impact Assessment (Law No. 86 on Environmental Impact Assessment of May 29, 2014); Performance Requirements -

Draft the Prut River Basin Management Plan 2016

Environmental Protection of International River Basins This project is implemented by a Consortium led by Hulla and Co. (EPIRB) HumanDynamics KG Contract No 2011/279-666, EuropeAid/131360/C/SER/Multi Project Funded by Ministry of Environment the European Union DRAFT THE PRUT RIVER BASIN MANAGEMENT PLAN 2016 - 2021 Prepared in alignment to the EuropeanWater Framework Directive2000/60/EC Prepared by Institute of Ecology and Geography of the Academy of Sciences of Moldova Chisinau, 2015 Contents Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 5 1.General description of the Prut River Basin ................................................................................. 7 1.1. Natural conditions .......................................................................................................................... 7 1.1.1. Climate and vegetation................................................................................................................... 8 1.1.2. Geological structure and geomorphology ....................................................................................... 8 1.1.3. Surface water resources.................................................................................................................. 9 1.1.3.1. Rivers ............................................................................................................................. -

Road Infrastructure Development of Moldova

Government of The Republic of Moldova Ministry of Economy and Infrastructure Road infrastructure development Chisinau 2017 1 … Road Infrastructure Road network Public roads 10537 km including: National roads 3670 km, including: Asphalt pavement 2973 km Concrete pavement 437 km Macadam 261 km Local roads 6867 km, Asphalt pavement 3064 km Concrete pavement 46 km Macadam 3756 km … 2 Legal framework in road sector • Transport and Logistic Strategy 2013 – 2022 approved by Government Decision nr. 827 from 28.10.2013; • National Strategy for road safety approved by Government Decision nr. 1214 from 27.12.2010; • Road Law nr. 509 from 22.06.1995; • Road fund Law nr. 720 from 02.02.1996 • Road safety Law nr. 131 from 07.06.2007 • Action Plan for implementing of National strategy for road safety approved by Government Decision nr. 972 from 21.12.2011 3 … Road Maintenance in the Republic of Moldova • The IFI’s support the rehabilitation of the road infrastructure EBRD, EIB – National Roads, WB-local roads. • The Government maintain the existing road assets. • The road maintenance is financed from the Road Fund. • The Road Fund is dedicated to maintain almost 3000km of national roads and over 6000 km of local roads • The road fund is part of the state budget . • The main strategic paper – Transport and Logistics Strategy 2013-2022. 4 … Road Infrastructure Road sector funding in 2000-2015, mil. MDL 1400 976 461 765 389 1200 1000 328 800 269 600 1140 1116 1025 1038 377 400 416 788 75 200 16 15 583 200 10 2 259 241 170 185 94 130 150 0 63 63 84 2000 -

Delimitarea Teritorial-Administrativ# a Jude#Ului Cahul În Componen#A

www.ssoar.info Delimitarea teritorial-administrativă a judeţului Cahul în componenţa ţinutului Dunărea de Jos (1938-1940) Cornea, Sergiu Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Cornea, S. (2013). Delimitarea teritorial-administrativă a judeţului Cahul în componenţa ţinutului Dunărea de Jos (1938-1940). Analele Ştiinţifice ale Universităţii de Stat "Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu" din Cahul / Annals of the University of Cahul, 9, 96-105. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-69610-0 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de ANALELE ŞTIINŢIFICE ALE UNIVERSITĂŢII DE STAT „B. P. HASDEU” DIN CAHUL, VOL. IX, 2013 DELIMITAREA TERITORIAL-ADMINISTRATIVĂ A JUDEŢULUI CAHUL ÎN COMPONENŢA ŢINUTULUI DUNĂREA DE JOS (1938-1940) Sergiu CORNEA, Catedra de Științe Politice și Administrative The aspects regarding the territorial delimitation of Cahul County are briefly examined. A new territorial circumscription was introduced in Romania, under the Administrative Law from 1938 – the land that included some counties. The Cahul County was a part of Lower Danube Land. There are analyzed the ways of the territorial delimitation accomplishment of Cahul County as the component part of the Lower Danube Land. The two archival documents which are relevant for the studied topic are presented in Appendix. La momentul Marii Uniri din anul 1918 delimitarea teritorial-administrativă județului Cahul era realizată în baza prevederilor legii Despre constituirea județului Cahul și reorganizarea conducerii locale în județele Ismail și Cahul adoptată de Sfatul Țării la 29 ianuarie 1918. -

The Evolution of the Road Network on the Current Territory of the Republic of Moldova in the Period 1918-1940 Vitalie Mamot

ECOTERRA - Journal of Environmental Research and Protection The evolution of the road network on the current territory of the Republic of Moldova in the period 1918-1940 Vitalie Mamot Tiraspol State University, Chișinău, Republic of Moldova. Corresponding author: V. Mamot, [email protected] Abstract. In the history of the Republic of Moldova, the roads were one of the main premises which determined, to a large extent, the socio-economic development of the territory and of the population, who lived here. At the beginning, the roads represented natural itineraries of plains or valleys, in the riverbeds which missed any kind of arrangement. These itineraries were formed and shaped over a long historical period. Changes in the itinerary directions and contents occurred only in case of the geographical landscape modifications or in case of some changes of attraction poles in the network of human settlements under the influence of different natural, economic, social and military factors. The purpose of the article is to restore and analyse the evolution of the road network on the current territory of the Republic of Moldova in the interwar period (1918-1940), when the current territory of the Republic of Moldova was found within Greater Romania. Key Words: road network, roads, road transport, counties. Introduction. The evolution of the transport network is closely dependent on the influence of external and internal factors (Тархов 2005). The first category is attributed to the political and geographical factors (change of state borders, military actions etc.); economic and geographic (the network of human settlements, the direction and configuration of the main transport flows, the degree and character of the economic valorisation of the territory etc.); economic growth or economic crisis; the diffusion of technological innovations in the field of transport; physical and geographical factors. -

Bulgarians Print Page Close Window

World Directory of Minorities Europe MRG Directory –> Moldova –> Bulgarians Print Page Close Window Bulgarians Profile Bulgarians live in the rural south of Moldova; 65,662 according to the 2004 census. Some 79 per cent of Moldovan Bulgarians claim Bulgarian as their first language, and 68 per cent identify Russian as their second language. Historical context Like the Gagauz, Bulgarians arrived in Bessarabia in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries seeking refuge from Ottoman persecution. Bulgarian immigration was also encouraged by co-religionist Russia. Subsequently, many assimilated to Russian culture and the rest became highly Russified. The recorded numbers of Bulgarians in Moldova fell from some 177,000 at the time of the formation of the MASSR in 1940 to 88,000 in 1989. From the late 1980s, Moldovan Bulgarians established links to Bulgaria, and the Bulgarian minority in Moldova has been the subject of bilateral cooperation between Bulgaria and Moldova. In January 1999 Bulgarians in the Moldovan district of Taraclia, where about half of Moldova's Bulgarian population resides, voted in an illegal referendum to protest against proposed administrative boundary changes. The changes would have abolished Taraclia district (a Soviet-era raion) and attached the area to neighbouring Cahul county, in the process transforming the Bulgarian population from a two- thirds local majority to a minority of 16 per cent. The principal fear of local Bulgarians was that they would lose state subsidies for Bulgarian language tuition in the district if they no longer comprised a local majority. The result was a 92 per cent vote against the boundary change, indicating that local Moldovans had voted with the Bulgarian population against the changes, reportedly due to the proposed move of some social services out of Taraclia to Cahul. -

Cahul District in the First Weeks of the Soviet Occupation (June-August 1940) Cornea, Sergiu

www.ssoar.info Cahul district in the first weeks of the soviet occupation (june-august 1940) Cornea, Sergiu Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Cornea, S. (2020). Cahul district in the first weeks of the soviet occupation (june-august 1940). Journal of Danubian Studies and Research, 10(1), 152-165. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-69466-6 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de ISSN: 2284 – 5224 Journal of Danubian Studies and Research Cahul District in the First Weeks of the Soviet Occupation (June-August 1940) Sergiu Cornea1 Abstract: As a result of direct diplomatic and military pressure exerted by the Soviet Union and blackmail by Germany and Italy in support of the aggressor, in June 1940 the Romanian administration and army left the territory of Bessarabia. The aim of the research is to reconstruct the events that occurred in a very complex and equally controversial period in the history of Cahul county –the establishment of the soviet occupation regime in summer 1940. In order to elucidate the subject, was used the method of content analysis of the official documents drawn up by the competent authorities of the “Lower Danube” Land, contained in the archive funds. A reliable source of information on the early days of soviet occupation is the refugees’ testimonies from Bessarabia. -

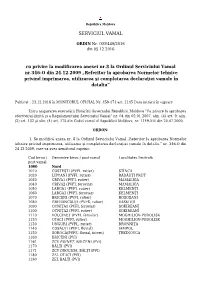

Serviciul Vamal

Republica Moldova SERVICIUL VAMAL ORDIN Nr. OSV449/2016 din 05.12.2016 cu privire la modificarea anexei nr.8 la Ordinul Serviciului Vamal nr.346-O din 24.12.2009 „Referitor la aprobarea Normelor tehnice privind imprimarea, utilizarea şi completarea declaraţiei vamale în detaliu” Publicat : 23.12.2016 în MONITORUL OFICIAL Nr. 459-471 art. 2145 Data intrării în vigoare Întru asigurarea executării Hotărîrii Guvernului Republicii Moldova ”Cu privire la aprobarea efectivului-limită și a Regulamentului Serviciului Vamal” nr. 04 din 02.01.2007, alin. (4) art. 9, alin. (2) art. 132 şi alin. (4) art. 175 din Codul vamal al Republicii Moldova, nr. 1149-XIV din 20.07.2000, ORDON: 1. Se modifică anexa nr. 8 la Ordinul Serviciului Vamal „Referitor la aprobarea Normelor tehnice privind imprimarea, utilizarea şi completarea declaraţiei vamale în detaliu.” nr. 346-O din 24.12.2009, care va avea următorul cuprins: Cod birou / Denumire birou / post vamal Localitatea limitrofă post vamal 1000 Nord 1010 COSTEȘTI (PVFI, rutier) STÎNCA 1020 LIPCANI (PVFI, rutier) RĂDĂUȚI PRUT 1030 CRIVA1 (PVFI, rutier) MAMALIGA 1040 CRIVA2 (PVFI, feroviar) MAMALIGA 1050 LARGA1 (PVFI, rutier) KELMENȚI 1060 LARGA2 (PVFI, feroviar) KELMENȚI 1070 BRICENI (PVFI, rutier) ROSOȘANI 1080 GRIMĂNCĂUȚI (PVFS, rutier) VASKIVȚI 1090 OCNIȚA1 (PVFI, feroviar) SOKIREANÎ 1100 OCNIȚA2 (PVFI, rutier) SOKIREANÎ 1110 VOLCINEȚ (PVFI, feroviar) MOGHILIOV-PODOLISK 1120 OTACI (PVFI, rutier) MOGHILIOV-PODOLISK 1130 UNGURI (PVFL, rutier) BRONNIȚA 1140 COSĂUȚI (PVFI, fluvial) IAMPOL 1150 SOROCA(PVFS, -

RAPORT Privind Activitatea Zonelor Economice Libere Din Republica Moldova Pentru Anul 2019

RAPORT privind activitatea Zonelor Economice Libere din Republica Moldova pentru anul 2019 ELABORAT DE MINISTERUL ECONOMIEI ȘI INFRASTRUCTURII CUPRINS Aspecte generale ..................................................................................................... 2 Forța de muncă și remunerarea muncii ............................................................. 3 Investiții ................................................................................................................... 3 Activitatea de producere ....................................................................................... 5 Contribuția zonelor economice libere în economia națională ..................... 9 Concluzii .................................................................................................................. 12 1 Aspecte generale Zonele economice libere din Republica Moldova își desfășoară activitatea în conformitate cu prevederile Legii nr.440/2001 cu privire la zonele economice libere, Legile privind zonele economice libere și actele normative de punere în aplicare a lor. Pe parcursul anului 2019 pe teritoriul Republicii Moldova au activat 7 zone economice libere (zone ale antreprenorialului liber), care înregistrau 34 subzone. Din numărul total de subzone, 55,88% sau 15 subzone au fost create în anul 2018, și anume: ZAL „Expo-Business-Chişinău” – 1 subzonă, ZEL „Bălţi” – 6 subzone, ZEL „Ungheni- Business” – 8 subzone. Este de menționat că în 2019 nu au fost create zone și subzone noi. Tabelul 1. Subzonele zonelor economice libere