From Candle Light to Contemporary Lighting Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stagehand Course Curriculum

Alaska Center for the Performing Arts Stagehand Training Effective July 1, 2010 1 Table of Contents Grip 3 Lead Audio 4 Audio 6 Audio Boards Operator 7 Lead Carpenter 9 Carpenter 11 Lead Fly person 13 Fly person 15 Lead Rigger 16 Rigger 18 Lead Electrician 19 Electrician 21 Follow Spot operator 23 Light Console Programmer and Operator 24 Lead Prop Person 26 Prop Person 28 Lead Wardrobe 30 Wardrobe 32 Dresser 34 Wig and Makeup Person 36 Alaska Center for the Performing Arts 2 Alaska Center for the Performing Arts Stagecraft Class (Grip) Outline A: Theatrical Terminology 1) Stage Directions 2) Common theatrical descriptions 3) Common theatrical terms B: Safety Course 1) Definition of Safety 2) MSDS sheets description and review 3) Proper lifting techniques C: Instruction of the standard operational methods and chain of responsibility 1) Review the standard operational methods 2) Review chain of responsibility 3) Review the chain of command 4) ACPA storage of equipment D: Basic safe operations of hand and power tools E: Ladder usage 1) How to set up a ladder 2) Ladder safety Stagecraft Class Exam (Grip) Written exam 1) Stage directions 2) Common theatrical terminology 3) Chain of responsibility 4) Chain of command Practical exam 1) Demonstration of proper lifting techniques 2) Demonstration of basic safe operations of hand and power tools 3) Demonstration of proper ladder usage 3 Alaska Center for the Performing Arts Lead Audio Technician Class Outline A: ACPA patching system Atwood, Discovery, and Sydney 1) Knowledge of patch system 2) Training on patch bays and input signal routing schemes for each theater 3) Patch system options and risk 4) Signal to Voth 5) Do’s and Don’ts B: ACPA audio equipment knowledge and mastery 1) Audio system power activation 2) Installation and operation of a mixing consoles 3) Operation of the FOH PA system 4) Operation of the backstage audio monitors 5) Operation of Center auxiliary audio systems a. -

American New Wave

Newsletter April 2021 SPOTLIGHT AMERICAN NEW WAVE IN THE SUMMER OF 2021, THE SCENOGRAPHER BEGINS ITS FIRST ‘OVERSEAS JOURNEY’ TO DISCOVER DESIGN FOR LIVE PERFORMANCE BY YOUNG CREATIVES FROM THE 1980S TO THE PRESENT DAY. FOR THE FIRST TIME, A EUROPEAN THEATRE MAGAZINE IS ENDEAVOURING TO GIVE AMPLE SPACE TO YOUNG AMERICAN DIRECTORS, SET AND COSTUME DESIGNERS WHO ARE AMONG THE MOST REPRESENTATIVE ON THE THEATRE SCENE AND WHO HAVE MADE – OR ARE MAKING - A NAME FOR THEMSELVES AT THE TURN OF THIS CENTURY. A BROAD-BASED PANORAMA OF THE VITALITY AND ORIGINALITY OF THEATRE IN THE UNITED STATES, A MULTICULTURAL GALAXY MADE UP OF A DIVERSITY OF ETHNIC INFLUENCES WILL TAKE SHAPE. The prestigious selection includes includes the following authors: BEOWULF BORITT (Set and Costume Designer); THADDEUS STRASSBERGER (Director and Set Designer); WILSON CHIN (Set Designer); ARNULFO MALDONADO (Set and Costume Designer), DAVID CHACON PEREZ (Director and Set Designer); ALEX TIMBERS (Director and Writer). BEOWULF BORITT is a New York City-based scenic designer for theater. He is known for his Tony Award winning design for the play Act One in 2014 (This issue is the first in the collection. It is already available in both digital & print editions.). Read more: https://www.thescenographer.org/boritt-beowulf/ THADDEUS STRASSBERGER is an American and citizen of the Cherokee Nation opera director and scenic designer. In 2005 he was awarded the European Opera Directing Prize by Opera Europa for his work on Opera Ireland’s production of Rossini’s La Cenerentola. WILSON CHIN is an award-winning production designer and producer from Redwood City, CA and based in New York City. -

Resume Examples

RÉSUMÉ TEMPLATES The following examples are provided to help you create your first résumé. There are six templates: 1) actor 2) designer/technician 3) stage manager 4) director 5) playwright 6) first-time résumé for someone just out of high school, combined with a general theatre résumé covering multiple areas of experience Length: An actor’s résumé should be a single page in length. When attached to a headshot, it should be trimmed to 8” x 10”. Résumés for other areas do not need to be limited to one page. There are many possible variations in style and format, and each template has a slightly different approach. Look over all of the samples for formatting ideas, even those that do not apply to your specific area of interest. You are also encouraged to contact faculty for advice and feedback on your drafts. Please note, résumés for graduate schools in theatre, professional theatres, and theatre internships are different from your typical business résumés. The sample résumés provided by the Center for Community Engagement and Career Education <http://www.csub.edu/cece/students/who_method.shtml> are useful if you are applying for a position outside of theatre, but their formats should not be used for jobs or graduate school applications within the theatre field. ACTOR TEMPLATE DAVID DRAMA [email protected] Height: 5’ 11” (661) 123-5678 Hair: Brown Tenor Theatre Death of a Salesman Biff Anita DuPratt Bakersfield Community Theatre Lend Me a Tenor Max Zoe Saba CSU Bakersfield Antigone in New York Sasha * Maria-Tania Becerra CSUB Evita Magaldi Mandy Rees CSUB Richard III Hastings Peter Brook Empty Space “Wiley and the Hairy Man” Wiley Kamala Kruszka CSUB and on tour “Unwrapped” (premiere) John Jessica Boles CSUB * Kennedy Center American College Theater Festival Irene Ryan Acting Scholarship nominee Education/Training B.A. -

Master Electrician

MASTER ELECTRICIAN Position Description Position Title: Circle Theatre Master Electrician Reports To: Technical Director and Lighting Designer Compensation: $500.00 per show stipend - paid at end of run Total Hours: Varies by needs of show Work Dates: Cabaret, July 5-Aug 1; Noises Off! Aug 2-29; Hair, Aug 30 – Sept 26. *Dates include the performance runs, which MEs are not required to attend but will need to be available to come in for repairs if needed during the run of the show. General Purpose Responsible for reading lighting designers plans and implementing the hanging of instruments; work with the Lighting Designer during focus and tech week. Up to 3 positions to fill (or one person for all three shows). 1 load-in/focus/strike period per production, $500 stipend per production. Minimum Job Requirements Education / Experience • Experience with theatrical stage lighting (conventional and LED), and with standard lighting conversion (i.e. desk lamps conversion to stage pin) Experience • Photography, graphic design, communications LIMITATIONS AND DISCLAIMER The above internship description is meant to describe the general nature and level of work being performed; it is not intended to be construed as an exhaustive list of all responsibilities, duties and skills required for the position. All job requirements are subject to possible modification to reasonably accommodate individuals with disabilities. Some requirements may exclude individuals who pose a direct threat or significant risk to the health and safety of themselves or other employees. This job description in no way states or implies that these are the only duties to be performed by the employee occupying this position. -

ANDREA BECHERT Scenic Designer / Scenographer

ANDREA BECHERT USA local 829 SCENIC DESIGNER / SCENOGRAPHER 1116 E. 46th Street, #2W, Chicago, IL 60653 * cell phone: 650-533-6059 * email: [email protected] Website: WWW.SCORPIONDESIGNS.NET CURRENT PROJECTS TheatreWorks The Country House (director: Robert Kelley – opens August, 2015) Palo Alto, CA Douglas Morrison Theatre By the Way, Meet Vera Stark (director: Dawn Monique Williams – Hayward, CA opens August, 2015) Center Repertory Theatre Vanya & Sonia & Masha & Spike (director: Mark Phillips – opens October, 2015) Walnut Creek, CA University of Michigan American Idiot (director: Linda Goodrich – opens October, 2015) Ann Arbor, MI RECENT PROJECTS TheatreWorks Sweeney Todd (director Robert Kelley - October 2014) Palo Alto, CA The Starlight Theatre Mary Poppins (director: Michael Webb - June, 2015) Rockford, Illinois The Last Five years (director: Michael Webb - June, 2015) Memphis (director: Michael Webb - June, 2015) Young Frankenstein (director: Michael Webb - June, 2015) University of Miami Faculty, Scenic Designer, and Scenic Artist (Fall semester, 2014) Served as Scenic Designer for a new production of Carmen, written and directed by Moises Kaufman, in collaboration with Techtonic Theatre Company 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee (director: Greg Brown – Sept. 2014) Courses taught: Drawing for the Theatre History of Decor ILLUSTRATIVE LIST OF SCENIC DESIGNS (FULL LIST PROVIDED UPON REQUEST – OVER 300) TheatreWorks 28 productions between 1997 - 2015, including: Palo Alto, California Sweeney Todd (director Robert Kelley -

Backstage Lighting Terminology

Break-out: Adapter consisting of multiple receptacles (FM) wired to a single multipin (M) connector; may be a box or a cable assembly. Synonym: Break-out Box, Fan-out Burn Out: Failed lamp or color media that is burned through Channel: Specific control parameter encompassing single or multiple device attributes (lighting dimmers, audio signals, etc.) controlled as a unit Lighting and Electrics Terminology (A-Le) Channel Hookup: Paperwork designating the connection of Adapter: Electrical accessory that transitions between dimmer circuits to channels of control dissimilar connectors; may be a molded unit, box or cable assembly Circuit: Path for electricity to flow from the source, through a conductor, to a device(s) Amperes: Unit of measure for the quantity of electricity flowing in a conductor. Synonym: A, Amp, Current Circuit Breaker: Mechanical/Electrical device that is designed to automatically open (trip) if the current exceeds the rated Automated Luminaire: Lighting instrument with attributes level protecting the circuit; may be operated manually that are remotely controlled. Synonym: Automated Fixture, Synonym: Breaker, CB, OCPD, Overcurrent Protective Device Automated Light, Computerized Light, Intelligent Light, Motorized Light, Mover, Moving Light Color Extender: Top hat with color media holder. Synonym: Gel Extender Backlight: A lighting source that is behind the talent or subject from the viewers perspective. Synonym: Backs, Back Color Frame: Metal or heat resistant device that holds the Wash, Bx, Hair Light, Rim Light color media in front of a luminaire. Synonym: Gel Frame Balcony Rail: Lighting position mounted in front of or on the Color Media: Translucent material used to color light face of the balcony. -

Stage Lighting Technician Handbook

The Stage Lighting Technician’s Handbook A compilation of general knowledge and tricks of the lighting trade Compiled by Freelancers in the entertainment lighting industry The Stage Lighting Technician's Handbook Stage Terminology: Learning Objectives/Outcomes. Understanding directions given in context as to where a job or piece of equipment is to be located. Applying these terms in conjunction with other disciplines to perform the work as directed. Lighting Terms: Learning Objectives/Outcome Learning the descriptive terms used in the use and handling of different types of lighting equipment. Applying these terms, as to the location and types of equipment a stagehand is expected to handle. Electrical Safety: Learning Objectives/Outcomes. Learning about the hazards, when one works with electricity. Applying basic safety ideas, to mitigate ones exposure to them in the field. Electricity: Learning Objectives/Outcomes. Learning the basic concepts of what electricity is and its components. To facilitate ones ability to perform the mathematics to compute loads, wattages and the like in order to safely assemble, determine electrical needs and solve problems. Lighting Equipment Learning Objectives/Outcomes. Recognize the different types of lighting equipment, use’s and proper handling. Gain basic trouble shooting skills to successfully complete a task. Build a basic understanding of applying these skills in the different venues that we work in to competently complete assigned tasks. On-sight Lighting Techniques Learning Objectives/Outcomes. Combing the technical knowledge previously gained to execute lighting request while on site, whether in a ballroom or theatre. Approaches, to lighting a presentation to aspects of theatrical lighting to meet a client’s expectations. -

Master Electrician

Longwood University 2013 Master Electrician Weekly: • Ensure that you meet with the lighting designer to discuss any ideas for how to overcome any unusual lighting challenges and provide an update to the overall process. Rehearsal Period: • Meet with the lighting designer shortly after receiving this position. o Discuss the production concept. o Be sure to receive the light plot and other paperwork. • Hold a workshop with all lighting crew members (electricians, spotlight operators, and board operator). o The workshop will be run by your and supervised by the lighting designer. o Cover all the basics of working with lighting. • Analyze all the lighting paperwork. o Ensure the realization of the light plot completely. o Create a list of what instruments, gels and specialty equipment will be need to implement the design. • Create any additional paperwork not given to you by the lighting designer. o Make sure the lighting designer and stage manager receive this paperwork. • Create and maintain an inventory of instruments, gels, and special effects. • Meet with the lighting designer a second time. o Discuss a tentative focus call schedule, any special positions or effects and the equipment inventory/orders. • Create a crew call schedule. Notify the technical director of crew calls. o Send out crew calls to electricians as early as possible. • Maintain all lighting instruments, cable, and accessories during the production. o Keep the mezzanine and catwalk neat, clean, and safe. • You are responsible for keeping all of the electrics paperwork up-to-date and distributed to the appropriate individuals. • You must personally implement any specialty lighting/electrical work. -

Head Electrician

JOB DESCRIPTION Job Title: Head Electrician Department: Production Reports To: Technical Director FLSA Status: Non-Exempt This position is covered by a collective bargaining agreement between I.A.T.S.E. Local 1 and the Apollo Theater. Organization: Founded in 1991, The Apollo Theater Foundation, Inc. is dedicated to the preservation and development of the legendary Apollo Theater through the Apollo Experience of world-class live performances and education programs that: Honor the influence and advance the contributions of African-American artists; and Advance emerging creative voices across cultural and artistic media. Our vision is to expand the reach of the Apollo Experience to a worldwide audience. This position is covered by the Apollo's Collective Bargaining Agreement with Local One. Both Union and Non-Union candidates are invited to apply. Position Summary: Manage, maintain, and operate theatrical lighting systems and equipment to ensure the timely and accurate realization of all lighting elements for The Apollo Theater in both the Main stage and the Sound Stage. The Head Electrician is responsible for scheduling and managing over hire electricians. Essential Duties and Responsibilities during technical rehearsals and performances: Consult with Designer, TD and/or PM to determine use of circuits for lighting plots Supervise the strike of theatrical lighting and equipment and restore of House Hang Responsible for hanging and focusing the lighting plots Supervise the crew during the Lx hang, and focus Move, re-focus, re-patch -

![Julia Elaine Mills [JEM]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2555/julia-elaine-mills-jem-1392555.webp)

Julia Elaine Mills [JEM]

Julia Elaine Mills [email protected] Owner: Cerulean Blue, LLC (917)975.5150 IATSE Local 52 Hire www.juliafilm.com Australian Cinematographer’s [JEM] IMDB: Julia Elaine Mills Society Member PROFESSIONAL WORK Sony Entertainment NAB Floor Representative for F5 and 4K Cameras – NAB, Las Vegas, April, 2013 Monkey Bay Productions (Production Intern/International Communication Liaison) – France, Summer 2012 Eastern Effects Lighting and Grip Equipment Rental House (Day Player/Contractor) – Summer 2011 Handheld Films Camera Rental House (Intern) – Summer 2011 City Stage (Sound Stage) Production Facility (Production Intern) – Spring 2011 NYU Tisch Film Teaching Soundstage (Camera Classes Technical Assistant) – Fall 2012‐Spring 2013 FILM EXPERIENCE Features/TV/Commercials “Royal Pains” USA Network Grip: TV Drama “Elementary” CBS Grip: TV Drama “The Michael J Fox Show” NBC Grip: TV Comedy “The Following” Fox Grip: TV Drama “The Blacklist” NBC Grip: TV Drama “The Carrie Diaries” HBO Grip: TV Comedy “Us & Them” Fox Grip: TV Comedy “Alpha House” Amazon Original Grip: TV Comedy Drama “Shelter” BiFrost Pictures Grip/BBG: Feature starring Jennifer Director Paul Bettany Connelly and Anthony Mackie “Petunia” Yale Productions/Cranium Ent. Grip: Feature starring Thora Birch and Producers Jordan Yale LeVine, Thora Birch Brittany Snow “Person of Interest” CBS Grip/Electrician: TV Drama “Squirrels to the Nuts” Lagniappe Films Grip/Electrician: Comedy starring Director Peter BogdanoVich Jennifer Anniston and Owen Wilson “Beware the Night” Screen Gems -

HORIZON THEATRE MASTER ELECTRICIAN Horizon Theatre

HORIZON THEATRE MASTER ELECTRICIAN Horizon Theatre Company, a 35-year old, professional contemporary theatre in Atlanta producing in a 172 seat theatre, seeks a part-time Master Electrician to ensure the timely and accurate realization of all lighting elements for Horizon’s 5-play main season, 2 Christmas plays and other productions/projects as needed. The Master Electrician will also manage and maintain performance-related electrics systems and equipment. Compensation hourly or by contract, depending on experience. Hours will average 50- 70 for each production plus approximately 10 hours per month for maintenance and additional hours for special upgrade/repair projects. Master Electrician is responsible for implementing the lighting design for each production and maintaining the integrity of the lighting design throughout the performance period. Duties include: Hanging, focusing, cabling and circuiting of the lighting plot for each production Hiring and supervision of electrics crew and/or interns for hang, focus and strike (in coordination with the technical directors). Assisting lighting designer during load-in, technical rehearsals and previews as needed Maintaining the design during the run of each show as needed Responding to emergency lighting needs, by phone or in person as needed Inventory and repair and maintenance of all lighting fixtures, cables, effects, power distribution, dimmers, networking and lighting control consoles. Organization and purchasing of all consumables including color gel, gobos, Sharpies, and gaffer tape. Planning and implementing of the circuiting of lights and electric power distribution. Documenting and tracking of all circuiting and system configuration in cooperation with the Lighting Designer. Patching assignments of the control console based on the paperwork generated by the lighting designer and the planned circuiting. -

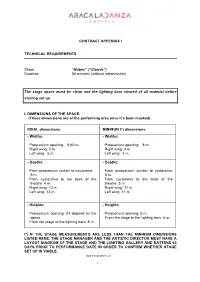

Tech Requirements

CONTRACT APPENDIX I TECHNICAL REQUIREMENTS Show: “Nubes” (“Clouds”) Duration: 50 minutes (without intermission) The stage space must be clean and the lighting bars cleared of all material before starting set up I. DIMENSIONS OF THE SPACE: (These dimensions are of the performing area once it’s been masked) IDEAL dimensions MÍNIMUN (*) dimensions - Widths: - Widths: Proscenium opening: 9,60 m. Proscenium opening: 8 m. Right wing: 5 m. Right wing: 4 m. Left wing: 5 m. Left wing: 4 m. - Depths: - Depths: From proscenium curtain to cyclorama: From proscenium curtain to cyclorama: 9 m. 8 m. From cyclorama to the back of the From cyclorama to the back of the theatre: 4 m. theatre: 3 m. Right wing: 13 m. Right wing: 11 m. Left wing: 13 m. Left wing: 11 m. - Heights: - Heights: Proscenium opening: it’ll depend on the Proscenium opening: 5 m. space From the stage to the lighting bars: 6 m. From the stage to the lighting bars: 8 m. (*) IF THE STAGE MEASUREMENTS ARE LESS THAN THE MINIMUM DIMENSIONS LISTED HERE, THE STAGE MANAGER AND THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR MUST HAVE A LAYOUT DIAGRAM OF THE STAGE AND THE LIGHTING GALLERY AND BATTENS 60 DAYS PRIOR TO PERFORMANCE DATE IN ORDER TO CONFIRM WHETHER STAGE SET UP IS VIABLE. www.aracaladanza.com 1 II. EQUIPMENT AND MATERIALS: (A hanging plot is attached) Material to be provided by the Theatre: • Black box to mask the stage in the Italian mode: 6 pairs of legs. (It can’t be performed with less than 4 pairs of legs). • System to fix all the legs.