Palatal (Adj.) a Term Used in the PHONETIC Classification of Speech

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phonological Theories Autosegmental/Metrical Phonology

Phonological Theories Autosegmental/Metrical Phonology Session 6 Phonological Theories Non-linear stress allocation Metrical phonology was an approach to word, phrase and sentence-stress definition which (a) defined stress as a syllabic property, not a vowel-inherent feature, and allowed a more flexible treatment of stress patterns in i) different languages, ii) different phrase-prosodic contexts. The prominence relations between syllables are defined by a (binary branching) tree, where the two branches from a node are labelled as dominant (s = strong) and recessive (w = weak) in their relation to each other. Four (quasi-independent) choices (are assumed to) determine the stress patterns that (appear to) exist in natural languages: 1 Right-dominant-foot vs. left-dominant-foot languages 2 Bounded vs. unbounded stress 3 Left-to-right vs. right-to-left word-stress assignment 4 Quantity-sensitive vs. quantity-insensitive languages Phonological Theories Right-dominant vs. left-dominant Languages differ in the tendency for the feet to have the strong syllable on the right or the left: Fr. sympho"nie fantas"tique Engl. "Buckingham "Palace F F F F s s s w w s w w s s w w s w Phonological Theories Bounded vs. unbounded stress (1) “Bounded” (vs. “unbounded”) is a concept that applies to the number of subordinate units that can be dominated by a higher node In metrical phonology it applies usually to the number of syllables that can be dominated by a Foot node (bounded = 2; one strong, one weak syllable to the left or the right; unbounded = no limit). This implies that bounded-stress languages have binary feet. -

Nigel Fabb and Morris Halle (2008), Meter in Poetry

Nigel Fabb and Morris Halle (2008), Meter in Poetry Paul Kiparsky Stanford University [email protected] Linguistics Department, Stanford University, CA. 94305-2150 July 19, 2009 Review (4872 words) The publication of this joint book by the founder of generative metrics and a distinguished literary linguist is a major event.1 F&H take a fresh look at much familiar material, and introduce an eye-opening collection of metrical systems from world literature into the theoretical discourse. The complex analyses are clearly presented, and illustrated with detailed derivations. A guest chapter by Carlos Piera offers an insightful survey of Southern Romance metrics. Like almost all versions of generative metrics, F&H adopt the three-way distinction between what Jakobson called VERSE DESIGN, VERSE INSTANCE, and DELIVERY INSTANCE.2 F&H’s the- ory maps abstract grid patterns onto the linguistically determined properties of texts. In that sense, it is a kind of template-matching theory. The mapping imposes constraints on the distribution of texts, which define their metrical form. Recitation may or may not reflect meter, according to conventional stylized norms, but the meter of a text itself is invariant, however it is pronounced or sung. Where F&H differ from everyone else is in denying the centrality of rhythm in meter, and char- acterizing the abstract templates and their relationship to the text by a combination of constraints and processes modeled on Halle/Idsardi-style metrical phonology. F&H say that lineation and length restrictions are the primary property of verse, and rhythm is epiphenomenal, “a property of the way a sequence of words is read or performed” (p. -

Printed 4/10/2003 Contrasts in Japanese: a Contribution to Feature

Printed 4/10/2003 Contrasts in Japanese: a contribution to feature geometry S.-Y. Kuroda UCSD CORRECTIONS AND ADDITIONS AFTER MS WAS SENT TO TORONTO ARE IN RED. August, 2002 1. Introduction . 1 2. The difference between Itô & Mester's and my account . 2 3. Feature geometry . 6 3.1. Feature trees . 6 3.2. Redundancy and Underspecification . 9 4. Feature geometry and Progressive Voicing Assimilation . 10 4.1. Preliminary observation: A linear account . 10 4.2. A non-linear account with ADG: Horizontal copying . 11 5. Regressive voicing assimilation . 13 6. The problem of sonorants . 16 7. Nasals as sonorants . 18 8. Sonorant assimilation in English . 19 9. The problem of consonants vs. vowels . 24 10. Rendaku . 28 11. Summary of voicing assimilation in Japanese . 31 12. Conclusion . 32 References . 34 1 1. Introduction In her paper on the issue of sonorants, Rice (1993: 309) introduces HER main theme by comparing Japanese and Kikuyu with respect to the relation between the features [voice] and [sonorant]: "In Japanese as described by Itô & Mester....obstruents and sonorants do not form a natural class with respect to the feature [voice].... In contrast ... in Kikuyu both voiced obstruents and sonorants count as voiced ...." (1) Rice (1993) Japanese {voiced obstruents} ::: {sonorants} Kikuyu {voiced obstruents, sonorants} Here, "sonorants" includes "nasals." However, with respect to the problem of the relation between voiced obstruents and sonorants, the situation IN Japanese is not as straightforward as Itô and Mester's description might suggest. There Are three phenomena in Japanese phonology that relate to this issue: • Sequential voicing in compound formation known as rendaku,. -

Common and Distinct Neural Substrates for Pragmatic, Semantic, and Syntactic Processing of Spoken Sentences: an Fmri Study

Common and Distinct Neural Substrates for Pragmatic, Semantic, and Syntactic Processing of Spoken Sentences: An fMRI Study G.R.Kuperberg and P.K.McGuire Downloaded from http://mitprc.silverchair.com/jocn/article-pdf/12/2/321/1758711/089892900562138.pdf by guest on 18 May 2021 Institute of Psychiatry, London E.T.Bullmore Institute of Psychiatry, London and the University of Cambridge M.J.Brammer, S.Rabe-Hesketh, I.C.Wright, D.J.Lythgoe, S.C.R.Williams, and A.S.David Institute of Psychiatry, London Abstract & Extracting meaning from speech requires the use of difference between conditions in activation of the left-super- pragmatic, semantic, and syntactic information. A central ior-temporal gyrus for the pragmatic experiment than the question is:Does the processing of these different types of semantic/syntactic experiments; (2) a greater difference be- linguistic information have common or distinct neuroanatomi- tween conditions in activation of the right-superior and middle- cal substrates? We addressed this issue using functional temporal gyrus in the semantic experiment than in the syntactic magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to measure neural activity experiment; and (3) no regions activated to a greater degree in when subjects listened to spoken normal sentences contrasted the syntactic experiment than in the semantic experiment. with sentences that had either (A) pragmatical, (B) semantic These data show that, while left- and right-superior-temporal (selection restriction), or (C) syntactic (subcategorical) viola- regions may be differentially involved in processing pragmatic tions sentences. All three contrasts revealed robust activation of and lexico-semantic information within sentences, the left- the left-inferior-temporal/fusiform gyrus. -

Modeling Subcategorization Through Co-Occurrence Outline

Introducing LexIt Building Distributional Profiles Ongoing Work Conclusions Outline Modeling Subcategorization Through Co-occurrence 1 Introducing LexIt A Computational Lexical Resource for Italian Verbs The Project Distributional Profiles 1 2 Gabriella Lapesa ,AlessandroLenci 2 Building Distributional Profiles Pre-processing 1University of Osnabr¨uck, Institute of Cognitive Science Subcategorization Frames 2 University of Pisa, Department of Linguistics Lexical sets Selectional preferences Explorations in Syntactic Government and Subcategorisation nd University of Cambridge, 2 September 2011 3 Ongoing Work 4 Conclusions Gabriella Lapesa, Alessandro Lenci Modeling Subcategorization Through Co-occurrence 2/ 38 Introducing LexIt Introducing LexIt Building Distributional Profiles The Project Building Distributional Profiles The Project Ongoing Work Distributional Profiles Ongoing Work Distributional Profiles Conclusions Conclusions Computational approaches to argument structure LexIt: a computational lexical resource for Italian The automatic acquisition of lexical information from corpora is a longstanding research avenue in computational linguistics LexIt is a computational framework for the automatic acquisition subcategorization frames (Korhonen 2002, Schulte im Walde and exploration of corpus-based distributional profiles of Italian 2009, etc.) verbs, nouns and adjectives selectional preferences (Resnik 1993, Light & Greiff 2002, Erk et al. 2010, etc.) LexIt is publicly available through a web interface: verb classes (Merlo & Stevenson 2001, Schulte im Walde 2006, http://sesia.humnet.unipi.it/lexit/ Kipper-Schuler et al. 2008, etc.) Corpus-based information has been used to build lexical LexIt is the first large-scale resource of such type for Italian, resources aiming at characterizing the valence properties of predicates cf. VALEX for English (Korohnen et al. 2006), LexSchem for fully on distributional ground French (Messiant et al. -

New Cambridge History of the English Language

New Cambridge History of the English Language Volume III: Change, transmission and ideology Editor: Joan Beal (Sheffield) I The transmission of English 1. Dictionaries in the history of English (John Considine) 2. Writing grammars for English (Ingrid Tieken) 3. Speech representation in the history of English (Peter Grund) 4. The history of English in the digital age (Caroline Tagg and Melanie Evans) 5. Teaching the history of English (Mary Hayes) 6. Internet resources for the history of English (Ayumi Miura) II Tracing change in the history of English 7. The history of English style (Nuria Yáñez Bouza / Javier Perez Guerra) 8. The system of verbal complementation (Hendrik de Smet) 9. Tense and aspect in the history of English (Teresa Fanego) 10. Development of the passive (Peter Petré) 11. Adverbs in the history of English (Ursula Lenker) 12. The story of English negation (Gabriella Mazzon) 13. Case variation in the history of English (Anette Rosenbach) 14. The noun phrase the history of English (Wim van der Wurff) 15. Relativisation (Cristina Suárez Gómez) 16. The development of pragmatic markers (Laurel Brinton) 17. Recent syntactic change in English (Jill Bowie and Bas Aarts) 18. Semantic change (Justyna Robinson) 19. Phonological change (Gjertrud Stenbrenden) 20. The history of R in English (Patrick Honeybone) 21. Reconstructing pronunciation (David Crystal) 22. Spelling practices and emergent standard writing (Juan Camilo Conde Silvestre and Juan Manuel Hernández Campoy) NewCHEL Vol. 3: Change, transmission and ideology Page 2 of 62 III Ideology, society and the history of English 23. The ideology of standard English (Lesley Milroy) 24. English dictionaries in the 18th and 19th centuries (Charlotte Brewer) 25. -

Comparing PENTA to Autosegmental-Metrical Phonology

Comparing PENTA to Autosegmental-Metrical Phonology Janet B. Pierrehumbert University of Oxford Feb 16, 2017 1 Introduction In this volume, Xu, Prom-on and Liu provide an overview of the recent work on the PENTA (parallel encoding and target approximation) model of prosody. This is a third-generation model of prosody and intonation. In characterizing the model this way, I am taking classic works based on audi- tory transcriptions, such as Bolinger (1958); Trager & Smith (1951); Crystal (1969), as first-generation models, and the autosegmental-metrical models (AM models) launched in the 1970’s and 1980’s as second-generation models. Second-generation models benefited enormously from the rise of computer workstations with specialized software for speech processing, which enabled researchers to examine thousands of f0 contours and to create experimental stimuli in which melodic characteristics of speech were varied in a controlled manner. However, the developers of AM models did not yet have the in- ference and optimization methods that have played such a central role in the development of PENTA. Generative AM algorithms, such as those laid out in Anderson et al. (1984); Beckman & Pierrehumbert (1986), were very seat-of-the pants efforts, compared to the multi-parameter trajectories that are achieved with PENTA. So, we can ask whether PENTA has superseded the AM approach? To what extent has it built on insights of the earlier ap- proach? What aspects of the AM research program remain even now topics for future research? A central issue in addressing these questions is the comparison between prosody and word phonology. AM theory, a development within generative linguistics, had as one of its goals a unified formalism for describing seg- mental, rhythmic, and melodic aspects of speech at both the lexical and the phrasal levels. -

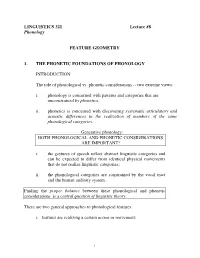

LINGUISTICS 321 Lecture #8 Phonology FEATURE GEOMETRY

LINGUISTICS 321 Lecture #8 Phonology FEATURE GEOMETRY 1. THE PHONETIC FOUNDATIONS OF PHONOLOGY INTRODUCTION The role of phonological vs. phonetic considerations -- two extreme views: i. phonology is concerned with patterns and categories that are unconstrained by phonetics; ii. phonetics is concerned with discovering systematic articulatory and acoustic differences in the realization of members of the same phonological categories. Generative phonology: BOTH PHONOLOGICAL AND PHONETIC CONSIDERATIONS ARE IMPORTANT! i. the gestures of speech reflect abstract linguistic categories and can be expected to differ from identical physical movements that do not realize linguistic categories; ii. the phonological categories are constrained by the vocal tract and the human auditory system. Finding the proper balance between these phonological and phonetic considerations is a central question of linguistic theory. There are two general approaches to phonological features: i. features are realizing a certain action or movement; 1 ii. features are static targets or regions of the vocal tract (this is the view that is embodied in the IPA). Study (1) on p. 137: These 17 categories are capable of distinguishing one sound from another on a systematic basis. However: if phonetics represent the physical realization of abstract linguistic categories, then there is a good reason to believe that a much simpler system underlies the notion “place of articulation.” By concentrating on articulatory accuracy, we are in danger of losing sight of the phonological forest among the phonetic trees. Example: [v] shares properties with the bilabial [∫] and the interdental [∂]; it is listed between these two (see above). However, [v] patterns phonologically with the bilabials rather than with the dentals, similarly to [f]: [p] → [f] and not [f] → [t]. -

What Is Linguistics?

What is Linguistics? Matilde Marcolli MAT1509HS: Mathematical and Computational Linguistics University of Toronto, Winter 2019, T 4-6 and W 4, BA6180 MAT1509HS Win2019: Linguistics Linguistics • Linguistics is the scientific study of language - What is Language? (langage, lenguaje, ...) - What is a Language? (lange, lengua,...) Similar to `What is Life?' or `What is an organism?' in biology • natural language as opposed to artificial (formal, programming, ...) languages • The point of view we will focus on: Language is a kind of Structure - It can be approached mathematically and computationally, like many other kinds of structures - The main purpose of mathematics is the understanding of structures MAT1509HS Win2019: Linguistics Linguistics Language Families - Niger-Congo (1,532) - Austronesian (1,257) - Trans New Guinea (477) - Sino-Tibetan (449) - Indo-European (439) - Afro-Asiatic (374) - Nilo-Saharian (205) - Oto-Manguean (177) - Austro-Asiatic (169) - Tai-Kadai (92) - Dravidian (85) - Creole (82) - Tupian (76) - Mayan (69) - Altaic (66) - Uto-Aztecan (61) MAT1509HS Win2019: Linguistics Linguistics - Arawakan (59) - Torricelli (56) - Sepik (55) - Quechuan (46) - Na-Dene (46) - Algic (44) - Hmong-Mien (38) - Uralic (37) - North Caucasian (34) - Penutian (33) - Macro-Ge (32) - Ramu-Lower Sepik (32) - Carib (31) - Panoan (28) - Khoisan (27) - Salishan (26) - Tucanoan (25) - Isolated Languages (75) MAT1509HS Win2019: Linguistics Linguistics MAT1509HS Win2019: Linguistics Linguistics The Indo-European Language Family: Phylogenetic Tree -

Formal Phonology

FORMAL PHONOLOGY ANDRA´ S KORNAI This is the PDF version of the book Formal Phonology published in the series Out- standing Dissertations in Linguistics, Garland Publishing, New York 1995, ISBN 0-815-317301. Garland is now owned by Taylor and Francis, and an ISBN-13 has also been issued, 978-0815317302. To my family Contents Preface xi Introduction xiii 0.1 The problem xiii 0.2 The results xv 0.3 The method xix 0.4 References xxiv Acknowledgments xxvii 1 Autosegmental representations 3 1.1 Subsegmental structure 4 1.2 Tiers 6 1.3 Association 8 1.4 Linearization 12 1.4.1 The mathematical code 13 1.4.2 The optimal code 14 1.4.3 The scanning code 17 1.4.4 The triple code 21 1.4.5 Subsequent work 24 1.5 Hierarchical structure 25 1.6 Appendix 28 1.7 References 36 viii Formal Phonology 2 Rules 39 2.1 Data and control 40 2.2 The rules of autosegmental phonology 44 2.2.1 Association and delinking 46 2.2.2 Insertion and deletion 47 2.2.3 Concatenation and tier conflation 51 2.2.4 Templatic and Prosodic Morphology 54 2.2.5 Domain marking 58 2.3 Automata 60 2.3.1 Biautomata 61 2.3.2 Tone Mapping 63 2.3.3 Vowel projections 64 2.3.4 A reduplicative template 65 2.3.5 The role of automata 67 2.4 Multi-tiered representations 68 2.4.1 Tuple notation 69 2.4.2 Autosegmentalized tuples 69 2.4.3 Tier ordering 70 2.4.4 A distinguished timing tier 72 2.5 Appendix 73 2.5.1 Finite-stateness and regularity 74 2.5.2 The characterization of regular bilanguages 77 2.5.3 Implications for phonology 84 2.5.4 Subsequent work 88 2.6 References 91 3 Duration 97 3.1 The -

A Study of the Teaching and Learning of English Grammar with Special Reference to the Foundation Course in the Norwegian Senior High School

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives A Study of the Teaching and Learning of English Grammar with Special Reference to the Foundation Course in the Norwegian Senior High School by Tony Burner A Thesis Presented to The Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages The University of Oslo in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the MA degree Fall Term 2005 i List of abbreviations...........................................................................................iii List of figures..................................................................................................... iv List of tables....................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements ............................................................................................. v Chapter 1: Introduction.............................................................................. 6 1.1 Background ............................................................................................. 6 1.2 Aim ......................................................................................................... 8 1.3 Previous research..................................................................................... 9 1.4 Methodology ......................................................................................... 11 1.5 Structure of the thesis............................................................................ -

The Learnability of Metrical Phonology

The Learnability of Metrical Phonology Published by LOT phone: +31 30 253 6006 Janskerkhof 13 fax: +31 30 253 6406 3512 BL Utrecht e-mail: [email protected] The Netherlands http://wwwlot.let.uu.nl/ Cover illustration by Diana Apoussidou ISBN 978-90-78328-18-6 NUR 632 Copyright © 2007: Diana Apoussidou. All rights reserved. THE LEARNABILITY OF METRICAL PHONOLOGY ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof.mr. P.F. van der Heijden ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties ingestelde commissie, in het openbaar te verdedigen in de Aula der Universiteit op dinsdag 9 januari 2007, te 14.00 uur door Diana Apoussidou geboren te Mönchengladbach, Duitsland Promotiecommissie Promotor: prof. dr. P.P.G. Boersma Overige commissieleden: prof. dr. H.M.G.M. Jacobs prof. dr. R.W.J. Kager dr. W. Kehrein dr. N.S.H. Smith prof. dr. P. Smolensky Faculteit der Geesteswetenschappen Acknowledgements I consider myself very lucky to have had the support when writing this thesis, whether directly or indirectly, from the following people: Essential to starting and finishing this work is Paul Boersma. I thank him for his support as much as for challenging me, and for enabling me to push the limits. I thank my reading committee Haike Jacobs, René Kager, Wolfgang Kehrein, Norval Smith, and Paul Smolensky for their valuable comments; especially Wolfgang and Norval for enduring tedious questions about phonology. My paranymphs Maren Pannemann and Petra Jongmans never failed in supporting me; they prevented me from going nuts in quite some moments of panic.