Gioachino Rossini William Tell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meyerbeer Was One of the Most Significant Opera Composers of All Time

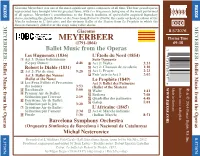

NAXOS NAXOS Giacomo Meyerbeer was one of the most significant opera composers of all time. The four grand operas represented here brought him his greatest fame, with Les Huguenots being one of the most performed of all operas. Meyerbeer’s contributions to the French tradition of opéra-ballet acquired legendary status, including the ghostly Ballet of the Nuns from Robert le Diable; the exotic orchestral colour of the Marche indienne in L’Africaine; and the virtuoso Ballet of the Skaters from Le Prophète in which the dancers famously glided over the stage using roller skates. DDD MEYERBEER: MEYERBEER: Giacomo 8.573076 MEYERBEER Playing Time (1791-1864) 69:38 Ballet Music from the Operas 7 Les Huguenots (1836) L’Étoile du Nord (1854) 47313 30767 1 Act 3: Danse bohémienne Suite Dansante Ballet Music from the Operas Ballet Music from (Gypsy Dance) 4:46 9 Act 2: Waltz 3:32 the Operas Ballet Music from Robert le Diable (1831) 0 Act 2: Chanson de cavalerie 1:18 2 Act 2: Pas de cinq 9:28 ! Act 1: Prayer 2:23 Act 3: Ballet des Nonnes @ Entr’acte to Act 3 2:02 (Ballet of the Nuns) Le Prophète (1849) 3 Les Feux Follets et Procession Act 3: Ballet des Patineurs 8 des nonnes 3:53 (Ballet of the Skaters) www.naxos.com Made in Germany Booklet notes in English ൿ 4 Bacchanale 5:00 # Waltz 1:41 & 5 Premier Air de Ballet: $ Redowa 7:08 Ꭿ Séduction par l’ivresse 2:19 % Quadrilles des patineurs 4:48 6 Deuxième Air de Ballet: 2014 Naxos Rights US, Inc. -

L Ethics Update 2010 L

COLUMBIAN LAWYERS ASSOCIATION First Judicial Department An Association Of Attorneys Of Italian American Descent 8 East 69th Street, New York, NY 10021 • Tel: (212) 661-1661 • Fax: 212) 557-9610 • www.columbianlawyers.com L L ETHICS UPDATE 2010 2010 THE NEW RULES OF CONDUCT OUR 55th YEAR Presented by Sarah Jo Hamilton, Esq., Scalise & Hamilton, LLP. Special Guest Speaker: Officers Hon. Angela Mazzarelli, Appellate Division, First Department Joseph DeMatteo President Wednesday, February 3, 2010 at 6:00 p.m. Sigismondo Renda First Vice President The Columbus Club – 8 East 69th Street, NY, NY Steven Savva Attendees receive 2 CLE Credits in Ethics (transitional) Second Vice President Maria Guccione RSVP (212) 661-1661, ext. 106 Treasurer Victoria Lombardi Members/Friends*: Dinner & Credits: $100.00 Executive Secretary Hon. Patricia LaFreniere Dinner Only: $100.00 Recording Secretary Marianne E. Bertuna Non-Members: Dinner & Credits: $150.00 Financial Secretary Dinner Only: $125.00; Credits Only: $50.00 Joseph Longo Parliamentarian * If your dues are not current, you will be charged the Non-Member Board Of Directors rate for attendance at the CLE Dinner Programs. Andrew Maggio - Chairman Gerry Bilotto - 2012 L Don’t Miss This Outstanding CLE Program! L Michael Scotto 2012 Paolo Strino 2012 *RSVP IS REQUIRED FOR THIS EXCEPTIONAL PROGRAM* John DeChiaro - 2011 Matthew Grieco - 2011 Effective April 2009, each branch of the Appellate Division adopted the American Bar Association’s Model Leonardo DeAngelica - 2011 Donna D. Marinacci - 2010 Rules of Professional Conduct, introducing a variety of significant changes to the ethics rules under which Thomas Laquercia - 2010 + attorneys have been practicing for years. -

Avant Première Catalogue 2018 Lists UNITEL’S New Productions of 2017 Plus New Additions to the Catalogue

CATALOGUE 2018 This Avant Première catalogue 2018 lists UNITEL’s new productions of 2017 plus new additions to the catalogue. For a complete list of more than 2.000 UNITEL productions and the Avant Première catalogues of 2015–2017 please visit www.unitel.de FOR CO-PRODUCTION & PRESALES INQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT: Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D · 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany Tel: +49.89.673469-613 · Fax: +49.89.673469-610 · [email protected] Ernst Buchrucker Dr. Thomas Hieber Dr. Magdalena Herbst Managing Director Head of Business and Legal Affairs Head of Production [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +49.89.673469-19 Tel: +49.89.673469-611 Tel: +49.89.673469-862 WORLD SALES C Major Entertainment GmbH Meerscheidtstr. 8 · 14057 Berlin, Germany Tel.: +49.30.303064-64 · [email protected] Elmar Kruse Niklas Arens Nishrin Schacherbauer Managing Director Sales Manager, Director Sales Sales Manager [email protected] & Marketing [email protected] [email protected] Nadja Joost Ira Rost Sales Manager, Director Live Events Sales Manager, Assistant to & Popular Music Managing Director [email protected] [email protected] CATALOGUE 2018 Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany CEO: Jan Mojto Editorial team: Franziska Pascher, Dr. Martina Kliem, Arthur Intelmann Layout: Manuel Messner/luebbeke.com All information is not contractual and subject to change without prior notice. All trademarks used herein are the property of their respective owners. Date of Print: February 2018 © UNITEL 2018 All rights reserved Front cover: Alicia Amatriain & Friedemann Vogel in John Cranko’s “Onegin” / Photo: Stuttgart Ballet ON THE OCCASION OF HIS 100TH BIRTHDAY UNITEL CELEBRATES LEONARD BERNSTEIN 1918 – 1990 Leonard Bernstein, a long-time exclusive artist of Unitel, was America’s ambassador to the world of music. -

André-Ernest-Modeste Grétry

pour la cour qu’il créée Zemire et Azor en 1771, où Marmontel parodie La Belle et la Bête. Cette nouvelle œuvre dédiée à Madame Du Barry lui vaut l’admiration de la famille royale, des courtisans puis du public, l’aspect fantastique de l’œuvre attisant la curiosité de l’auditoire, confondu par la mystérieuse scène du tableau magique… Triomphe absolu, et là encore Grétry donne le sentiment de proposer un nouveau type de spectacle. 1773 voit le succès du Magnifique écrit avec Sedaine, suivi de La Rosière de Salency, et surtout du premier “Grand Opéra” de Grétry, représenté à l’Opéra Royal de Versailles pour le Mariage du Comte d’Artois : Céphale et Procris. La nouvelle Reine, Marie-Antoinette, s’est tellement entichée de Grétry qu’elle devient la marraine de sa troisième fille en 1774, justement prénommée Antoinette. En six ans à peine, le jeune liégeois arrivé inconnu à Paris en est devenu le principal compositeur, stipendié par la cour… André-Ernest-Modeste Grétry Mais la représentation d’Iphigénie en Aulide de Gluck, au printemps 1774, est une 1741-1813 déflagration de modernité, et lorsque juste après, Céphale et Procris est présenté à l’Académie Royale de Musique, le public est déçu de son manque d’audace. Grétry est éclipsé par le Chevalier Gluck… La fausse magie en 1775, tièdement accueillie, Né à Liège dans une famille de musiciens, il intègre la maîtrise de la Collégiale Saint- est suivie du rebond des Mariages Samnites en 1776, au moment où les œuvres Denis où son père était premier violon. -

Don Carlos and Mary Stuart 1St Edition Pdf Free

DON CARLOS AND MARY STUART 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Friedrich Schiller | 9780199540747 | | | | | Don Carlos and Mary Stuart 1st edition PDF Book Don Carlos and Mary Stuart , two of German literature's greatest historical dramas, deal with the timeless issues of power, freedom, and justice. Showing It is an accessible Mary Stuart for modern audiences. Rather, the language is more colloquial and the play exhibits some extensive cuts. The title is wrong. I have not read much by Schiller as of yet, but I feel really inspired to pick up more plays now. A pair of tragedies from Friedrich Schiller, buddy to Goethe, and child of the enlightenment. June Click [show] for important translation instructions. As a global organization, we, like many others, recognize the significant threat posed by the coronavirus. Don Carlos and Mary Stuart. I am particularly impressed by Schiller, a Protestant, for his honest account of the good Queen Mary and the Roman religion. I've read several translations of this text, but this is the one I can most readily hear in the mouths of actors, especially Act 3, when the two women come face to face. This article on a play from the 18th century is a stub. Please contact our Customer Service Team if you have any questions. These are two powerful dramas, later turned into equally powerful operas. The Stage: Reviews. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Peter Oswald London: Oberon Books, , 9. Mary Stuart. Don Carlos is a bit too long, I think, though it is fantastic. Archived from the original on September 8, Jan 01, Glenn Daniel Marcus rated it really liked it. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zaab Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 46106 I I

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. Thefollowing explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page ($)''. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. Whan an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that die photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You w ill find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections w ith a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Friedrich Schiller - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Friedrich Schiller - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Friedrich Schiller(10 November 1759 – 9 May 1805) Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller was a German poet, philosopher, historian, and playwright. During the last seventeen years of his life, Schiller struck up a productive, if complicated, friendship with already famous and influential <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/johann-wolfgang-von- goethe/">Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe</a>. They frequently discussed issues concerning aesthetics, and Schiller encouraged Goethe to finish works he left as sketches. This relationship and these discussions led to a period now referred to as Weimar Classicism. They also worked together on Xenien, a collection of short satirical poems in which both Schiller and Goethe challenge opponents to their philosophical vision. <b>Life</b> Friedrich Schiller was born on 10 November 1759, in Marbach, Württemberg as the only son of military doctor Johann Kaspar Schiller (1733–96), and Elisabeth Dorothea Kodweiß (1732–1802). They also had five daughters. His father was away in the Seven Years' War when Friedrich was born. He was named after king Frederick the Great, but he was called Fritz by nearly everyone. Kaspar Schiller was rarely home during the war, but he did manage to visit the family once in a while. His wife and children also visited him occasionally wherever he happened to be stationed. When the war ended in 1763, Schiller's father became a recruiting officer and was stationed in Schwäbisch Gmünd. The family moved with him. Due to the high cost of living—especially the rent—the family moved to nearby Lorch. -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert Le Diable Online

cXKt6 [Get free] The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable Online [cXKt6.ebook] The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable Pdf Free Richard Arsenty ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #4398313 in Books 2009-03-01Format: UnabridgedOriginal language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.00 x .50 x 5.70l, .52 #File Name: 1847189644180 pages | File size: 19.Mb Richard Arsenty : The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Liobretto for Meyerbeer's "Robert le Diable"By radamesAn excellent publication which contained many stage directions not always reproduced in the nineteenth-century vocal scores and a fine translation. Useful at a time of renewed interest in this opera at the Royal Opera, Covent Garden Giacomo Meyerbeer, one of the most important and influential opera composers of the nineteenth century, enjoyed a fame during his lifetime hardly rivaled by any of his contemporaries. This eleven volume set provides in one collection all the operatic texts set by Meyerbeer in his career. The texts offer the most complete versions available. Each libretto is translated into modern English by Richard Arsenty; and each work is introduced by Robert Letellier. In this comprehensive edition of Meyerbeer's libretti, the original text and its translation are placed on facing pages for ease of use. About the AuthorRichard Arsenty, a native of the U.S. -

New Releases June 2017

NEW RELEASE JUNE 2017 NEW RELEASES JUNE 2017 www.dynamic.it • [email protected] DYNAMIC Srl • www.dynamic.it • [email protected] 1 NEW RELEASE JUNE 2017 DON CARLO GIUSEPPE VERDI First performed in French at the Paris Opera in 1867, Don Carlo is in many ways an amazingly innovative work. The opera seems to underline Verdi’s shift from the Manichean division between good and evil, which had been a clear, structural element of his dramaturgy up to that point in his career. In this opera, Verdi assembles all his mainstay music theatre themes: power, with its honours and burdens; the contrasts of impossible love; the conflict between father and son; and an oppressed people demanding freedom. Verdi radically revised the score in 1883, using an Italian libretto and reducing the opera from five acts to four. The popularity of Don Carlo has grown unremittingly ever since, with today's critics almost unanimously recognising it as one of Verdi’s greatest masterpieces, an opera that continues to reveal new gems. Daniel Oren is fully in control on the podium, ensuring unanimity between orchestra and singers. The Maestro softens the dark DON CARLO tones of the score, which are well reflected in the visuals, choosing Dramma lirico in four Acts instead to emphasise the various changes of mood. Composer KEY FEATURES GIUSEPPE VERDI (1813 – 1901) Excellent cast for the opening season of Festival Verdi – Teatro Regio di Parma. Libretto by Resounding success, sustained applause, especially for the Joseph Méry e Camille du Locle bass Michele Pertusi as Filippo II. Italian translation by Achille De Lauzières and Angelo Zanardini Available in CD, DVD, Bluray. -

Activity #1, Overture to William Tell

STUDENT ACTIVITIES Student Activities – Activity #1, Overture to William Tell William Tell is an opera written by the composer Gioachino Rossini. This famous piece is based upon the legend of William Tell and has been used in cartoons, movies, and even commercials! Listen to the Overture to William Tell and see if you recognize it! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YIbYCOiETx0 Read the Legend of William Tell. This was Rossini’s inspiration for writing the opera! THE LEGEND OF WILLIAM TELL William Tell is a Swiss folk hero. As the legend goes, William Tell was known as a mighty man who was an expert with the crossbow. After refusing to pay homage to the Austrian emperor, Tell was arrested and the emperor deemed that William and his son Walter be executed. However, the emperor would let them go free if William was able to shoot an apple off the head of his son! Walter nervously stood against a tree and an apple was placed upon his head. William successfully shot the apple from 50 steps away in front of a crowd of onlookers! William Tell and his never ending fight for liberty helped start the rebellion against the emperor and other tyrants as well. FWPHIL.ORG 1 STUDENT ACTIVITIES Activity #1, Overture to William Tell Listen to the musical excerpt again and answer the 5. Although there are no horses in the following questions. Rossini opera, this music was used as the theme song for “The Lone Ranger” 1. Do you recognize the overture to William Tell? as he rode his galloping horse! It has however, been used in commercials and even cartoons! Where else have you heard this piece? Explain. -

Schiller and Music COLLEGE of ARTS and SCIENCES Imunci Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures

Schiller and Music COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ImUNCI Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures From 1949 to 2004, UNC Press and the UNC Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures published the UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures series. Monographs, anthologies, and critical editions in the series covered an array of topics including medieval and modern literature, theater, linguistics, philology, onomastics, and the history of ideas. Through the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, books in the series have been reissued in new paperback and open access digital editions. For a complete list of books visit www.uncpress.org. Schiller and Music r.m. longyear UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures Number 54 Copyright © 1966 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons cc by-nc-nd license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses. Suggested citation: Longyear, R. M. Schiller and Music. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1966. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.5149/9781469657820_Longyear Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Longyear, R. M. Title: Schiller and music / by R. M. Longyear. Other titles: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures ; no. 54. Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [1966] Series: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: lccn 66064498 | isbn 978-1-4696-5781-3 (pbk: alk. paper) | isbn 978-1-4696-5782-0 (ebook) Subjects: Schiller, Friedrich, 1759-1805 — Criticism and interpretation.