Cacv 218/2005 in the High Court of the Hong Kong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women Readers of Middle Temple Celebrating 100 Years of Women at Middle Temple the Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for England and Wales

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple Middle Society Honourable the The of 2019 Issue 59 Michaelmas 2019 Issue 59 Women Readers of Middle Temple Celebrating 100 Years of Women at Middle Temple The Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for England and Wales Practice Note (Relevance of Law Reporting) [2019] ICLR 1 Catchwords — Indexing of case law — Structured taxonomy of subject matter — Identification of legal issues raised in particular cases — Legal and factual context — “Words and phrases” con- strued — Relevant legislation — European and International instruments The common law, whose origins were said to date from the reign of King Henry II, was based on the notion of a single set of laws consistently applied across the whole of England and Wales. A key element in its consistency was the principle of stare decisis, according to which decisions of the senior courts created binding precedents to be followed by courts of equal or lower status in later cases. In order to follow a precedent, the courts first needed to be aware of its existence, which in turn meant that it had to be recorded and published in some way. Reporting of cases began in the form of the Year Books, which in the 16th century gave way to the publication of cases by individual reporters, known collectively as the Nominate Reports. However, by the middle of the 19th century, the variety of reports and the variability of their quality were such as to provoke increasing criticism from senior practitioners and the judiciary. The solution proposed was the establishment of a body, backed by the Inns of Court and the Law Society, which would be responsible for the publication of accurate coverage of the decisions of senior courts in England and Wales. -

Cacv 277/2007 in the High Court of the Hong

CACV 277/2007 IN THE HIGH COURT OF THE HONG KONG SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION COURT OF APPEAL CIVIL APPEAL NO. 277 OF 2007 (ON APPEAL FROM HCMP NO. 5714 OF 2001) ______________________ IN THE MATTER OF THE ORGANIZED AND SERIOUS CRIMES ORDINANCE (CAP. 455) BETWEEN HUI YAT SING 8th Respondent WONG SUET MUI 9th Respondent and JOHN ROBERT LEES Receiver ______________________ Before : Hon Tang VP, Sakhrani J and Barma J in Court Date of Hearing : 22 February 2008 Date of Judgment: 29 February 2008 ______________________ JUDGMENT ______________________ Hon Tang VP (giving the judgment of the Court): Background 1. Certain realisable property (“the restrained assets”), held in the name of the 8 th and 9 th respondents, were the subject of a restraint order made on 27 October 2001 under section 15 of the Organized and Serious Crimes Ordinance, Cap. 455 (“the Ordinance”). 2. On 10 December 2001, Mr John Robert Lees and Mr Desmond Chung Seng Chiong were appointed joint and several receivers of the restrained assets pursuant to section 15(7) of the Ordinance. Subsequently, Mr Lees became the sole receiver. 3. The 8 th and 9 th respondents, who are husband and wife, were charged with the offence of conspiring between 1 September 1995 and October 2001, to deal with properties knowing or having reasonable grounds to believe that they represented the proceeds of an indictable offence, contrary to section 159A of the Crimes Ordinance, Cap. 200, and section 25 of the Ordinance (“the criminal proceedings”). 4. On 20 September 2002, Gall J varied the restraint order such that the 8 th and 9 th respondents were, inter alia, permitted to have the legal costs of their defence taxed at regular intervals and, thereafter, released from the restrained assets by the receivers to meet their taxed costs (para. -

32Nd LAWASIA Conference Conference Program

32nd LAWASIA Conference 5-8 November 2019 | Hong Kong SAR Conference Program _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Please note that the below is a preliminary conference program and subject to change. Information correct as at 3 October 2019. CPD Accreditation for Hong Kong SAR delegates A maximum of 14 CPD points will be awarded for attendance of the full programme Please note that the conference will be held across two different venues: The JW Marriott Hotel and the Hong Kong Convention & Exhibition Centre (HKCEC). Monday, 4 November 2019 1400 – 1800 LAWASIA Executive Committee Meeting ExCo Members only Tuesday, 5 November 2019 1000 – 1600 Annual LAWASIA Council Meeting LAWASIA Council Members only. This event is by direct invitation only. 1800 – 2000 Presidents’ Dinner Invitation only 1 Wednesday, 6 November 2019 0830 – 0930 Registration Ballroom Foyer, JW Marriott Hotel 0930 – 1030 Opening Ceremony Ballroom, JW Marriott Hotel Welcome Remarks by Mr Christopher Leong, President of LAWASIA Welcome Remarks by Ms Melissa Pang MH JP, President of The Law Society of Hong Kong Special Address by The Honourable Geoffrey Ma Tao-li GBM, Chief Justice of the Court of Final Appeal, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Special Address by The Honourable Teresa Cheng Yeuk-wah GBS SC JP, Secretary for Justice, The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region 1030 – 1100 Morning Refreshments & Networking Ballroom Foyer, JW Marriott Hotel 1100 – 1230 Plenary Session Ballroom, JW Marriott Hotel 1300 – 1430 Lunch & Guest Speech Renaissance Harbour View Hotel Note: One-way coach transfer from the JW Marriott Hotel to the Renaissance Harbour View Hotel will be provided. 1800 – 2200 Update on Global Legal Landscape and Welcome Reception & LAWASIA Cup Happy Valley Racecourse Note: Delegates will be required to make their own arrangements to and from Happy Valley Racecourse. -

Cacv 85/2009 in the High Court of the Hong Kong

CACV 85/2009 IN THE HIGH COURT OF THE HONG KONG SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION COURT OF APPEAL CIVIL APPEAL NO. 85 OF 2009 (ON APPEAL FROM HCMP NO. 2382 OF 2008) _____________________ IN THE MATTER of PCCW LIMITED (電訊盈科有限公司) and IN THE MATTER of the Companies Ordinance, Chapter 32 _____________________ Before: Hon Rogers VP, Lam and Barma JJ in Court Dates of Hearing: 16-18 & 20-22 April 2009 Date of Judgment: 22 April 2009 Date of Handing Down Reasons for Judgment: 11 May 2009 _______________________________ REASONS FOR JUDGMENT _______________________________ Hon Rogers VP: 1. This was an appeal from a judgment of Kwan J given on 6 April 2009. The matter before the judge was a petition that had been presented on 11 February 2009 by PCCW Limited 電訊盈科有限公司 (“the Company”). The petition sought sanction of a scheme of arrangement (“the Scheme”) pursuant to section 166 of the Companies Ordinance, Cap. 32 (“the Ordinance”), and confirmation of the reduction of the Company’s share capital involved in the Scheme, pursuant to section 59 of the Ordinance. 2. The Scheme is between the Company and the holders of the Scheme shares, namely all the shares of the Company other than those held by Starvest Limited (“Starvest”) and China Netcom Corporation (BVI) Limited (“Netcom BVI”) (“the Joint Offerors”) and by shareholders that are termed parties acting in concert with Starvest, namely Pacific Century Regional Developments Limited (“PCRD”) which is Starvest’s parent company, Pacific Century Group Holdings Limited (“PCGH”), Pacific Century Diversified Limited (“PCD”) and Eisner Investments Limited (“Eisner”). These companies are together referred to as “the Excluded Group”. -

How to Regulate Financial Advisors? I

1 This page is intentionally kept blank 2 CONTENT Sr. No. Document Page Number 1 Background 5 2 Tackling Conflict of Interest in Distribution of Financial Products 6 3 Structure of Proposed Regulations 8 4 Definitions 10 5 Coverage 11 6 Persons Exempt from the regulations 12 7 Registration Requirements 13 8 Obligations of an Investment Advisor 14 9 Execution Services 15 10 Outsourcing 16 11 Liability 17 12 Entities registered as Portfolio Managers 18 13 Public Comments 19 Exhibit I : Presentation made by FPSB India before High Level 14 21 Co-ordination Committee on Financial Markets (HLCCFM) - (2009) 15 Exhibit II : Paper on Service Tax on Mutual Fund Distribution - (2004) 37 16 Exhibit III : Consultation Paper by HLCCFM - (2009) 43 Exhibit IV : Discussion Draft [Investment Advisor Oversight Act of 17 75 2011] as presented in the U.S Congress - (2011) Exhibit V : FPSB India’s comments on SEBI (SRO Regulations), 2004, 18 105 and Draft SEBI (Investor Advisor Regulations), 2007 Exhibit VI : Regulation of Investment Advisors - Model for 19 141 Establishment of Self Regulatory Organization (SRO) - (2007) 20 Exhibit VII : About FPSB India 289 3 This page is intentionally kept blank 4 1. Background Paragraph No SEBI Concept Paper FPSB India’s Comments Section 11 (2)(b) of SEBI Act empowers SEBI to register and regulate working of Investment Advisors and such other 1.1 NC intermediaries who may be associated with securities market in any other manner. As decided by SEBI Board in its meeting dated March 22, 2007, SEBI had posted a consultative paper on the “Regulation of Investment Advisors” on its website inviting public comments. -

Administration's Paper on Assessment of the Statutory Compensations Of

CB(1)650/14-15(08) For Discussion 24 March 2015 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL PANEL ON DEVELOPMENT Assessment of the statutory compensations of resumed properties and resolution of disputes arising from land resumption INTRODUCTION This paper outlines the Government’s practice in assessing statutory compensations payable to legal owners of resumed properties in single or multiple ownership, as well as in resolving disputes arising from land resumption. LAND RESUMPTION AND COMPENSATION 2. To facilitate the implementation of public works projects or for other public purposes, the Government may need to resume landed properties, i.e. land and buildings, in accordance with the statutory provisions. The statutory power to resume most commonly applied is that found in the Lands Resumption Ordinance (Cap. 124) (LRO), which, together with the applicable common law principles, also provides for the underlying basis for assessing the statutory compensation payable to the affected owners. Notably, the “principle of equivalence” underlies the law of compensation: “the right (of the owner) to be put, so far as money can, in the same position as if his land had not been taken from him. In other words, he gains a money payment not less than the loss imposed on him in the public interest, but on the other hand no greater”. Horn v Sunderland Corp. [1941] 2 KB 26. Another established principle of compensation law is the so-called Pointe-Gourde rule, that compensation “cannot include an increase in value which is entirely due to the scheme underlying the acquisition.” Pointe Gourde Quarrying and Transport Co v Sub-Intendent of Crown Lands [1947] AC 565. -

Amity Visit to Singapore

MIDDLE TEMPLE AMITY VISIT TO SINGAPORE 21 TO 23 SEPTEMBER 2016 PART THREE FRIDAY 23 SEPTEMBER EVENTS MIDDLE TEMPLE AMITY VISIT TO SINGAPORE Friday 23 September 2016 Venue: Singapore Academy of Law, Supreme Court Level 6, Singapore Dress code: Lounge suits Travel: 08:00 coach from the Four Seasons Hotel 08:30 Registration 09:00 Panel 4 (Consecutive Sessions) Criminal Law - Joint Enterprise and Criminal Procedure Chair - Singapore - The Honourable Justice Tay Yong Kwang UK Speakers - Nicola Padfield and His Honour Judge Philip Bartle QC Singapore Speakers - N Sreenivasan SC and Mavis Chionh SC Developments in Family Law Chair - Singapore - The Honourable Judicial Commissioner Debbie Ong UK Speaker - Ann Hussey QC Singapore Speakers - Professor Leong Wai Kum and Michelle Woodworth 11.30 Coffee Break 12.00 Moot UK Participants - Karen Reid (MTYBA) and Ryan Turner (MTSA) Singapore Participants - Koh Swee Yen and Jordan Tan Judges - The Rt. Hon Lord Dyson (UK), The Honourable Mr Justice Barma JA (Hong Kong) and The Honourable Justice Steven Chong (Singapore) 13.30 Lunch 14:30 End of Conference Day Two 14:40 - 16:00 Tour of the National Gallery (meeting point at Padang Atrium, Information Counter, Level 1) MIDDLE TEMPLE AMITY VISIT TO SINGAPORE Speaker Biographies for Conference Day Two (In order of appearance) The Honourable Judge of Appeal Justice Tay Yong Kwang Supreme Court of Singapore Justice Tay Yong Kwang joined the Supreme Court in 1981, first as Assistant Registrar and then as Deputy Registrar. In 1989, he served in the Official Assignee and Public Trustee’s Office. He then served as District Judge from 1991-1997 at the Subordinate Courts (renamed as the State Courts in 2014). -

Cacv 28/2010 in the High Court of the Hong Kong Special

CACV 28/2010 IN THE HIGH COURT OF THE HONG KONG SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION COURT OF APPEAL CIVIL APPEAL NO. 28 OF 2010 (ON APPEAL FROM THE DECISIONS OF THE DISCIPLINARY COMMITTEE OF THE HONG KONG INSTITUTE OF CERTIFIED PUBLIC ACCOUNTANTS DATED 29 JUNE 2009 AND 24 DECEMBER 2009) ________________________ BETWEEN Ng Kay Lam Appellant and The Registrar of the Hong Kong Institute of Certified Public Accountants Respondent ________________________ Before: Hon Rogers VP, Le Pichon JA and Barma J in Court Date of Hearing: 17 November 2010 Date of Handing Down Judgment: 30 November 2010 ________________________ J U D G M E N T ________________________ Hon Rogers VP: 1. I agree with the judgment of Le Pichon JA. Hon Le Pichon JA: 2. This is an appeal by the respondent from (1) a decision of the Disciplinary Committee (“the Committee”) of the Hong Kong Institute of Certified Public Accountants (“the Institute”) of 29 June 2009 finding the complaint that the respondent had breached section 34(1)(a)(vi) of the Professional Accountants Ordinance, Cap. 50 (“the Ordinance”) proved and (2) an order of 24 December 2009 that the respondent be reprimanded, pay a penalty of $50,000 to the Institute and costs in the amounts specified in the order. At the conclusion of the hearing judgment was reserved which we now give. Background 3. The facts are undisputed and can be summarised as follows. 4. The respondent is a certified public accountant practising as a sole proprietor under the name of K.L. Ng & Company (“the firm”). The firm carried out the audit of Linfoot (Asia Pacific) Ltd (“LAPL”) for the year ended the 31 December 2003. -

附錄列表list of Appendices

! LIST OF APPENDICES Appendix 1 148 2003 !" Highlights of Events 2003 Appendix 2 154 !"#$% List of Judges and Judicial Officers Appendix 3 159 ! Structure of Courts Appendix 4 160 !"#$!%&!'( Membership List of the Judicial Officers Recommendation Commission Appendix 5 161 !"#$%&$'( Membership List of the Court Users’ Committees Appendix 6 164 !"#$%&#'(#)* Membership List of the Judicial Studies Board Appendix 7 166 !"#$!%&'()*+"#,- Training Activities Organised / Co-ordinated by the Judicial Studies Board Appendix 8 170 !"#$%&'(& APPENDIX 1LIST OF APPENDICES Number of Visits and Visitors to the Judiciary 147 Appendix 9 171 2002-2003 !"#$%&'() Expenditure and Revenue of the Judiciary for 2002-2003 ! Appendix 10 172 !"#$%&! Organisation of the Judiciary Administration ! Appendix 11 173 !"# $%&' Number of Complaints Against Judges and Judicial Officers ! Appendix 12 174 !"#$%&'( Number of Complaints Against the Judiciary Administration ==Appendix 1 2003 !" 2003 !" HIGHLIGHTS OF EVENTS 2003 HIGHLIGHTS OF EVENTS 2003 January March 9 !"#$#%%&'British Academy !"#$%&Jack Beatson Swansea 13 !"#$%&' ()*+,-./"01-./2345 !"#$%&'()!*+DL David Williams !"#$%&'(Jack Beatson Legislative Council Panel on Administration of Justice and Legal Services visited the Juvenile !"#$!%&' !"#$%&'()*Jack Beatson !David Willaims Courts of Kowloon City Magistrates’ Courts and Eastern Magistrates’ Courts !"#$%&'()*+, Professor Jack Beatson, Q.C., FBA, Chairman of the Faculty of Law of the University of Cambridge, 22 !"# $%&'()*++!,-./0123+456789:;< and Professor Sir David Williams, Q.C., DL, President of University of Wales, Swansea, the United The Chief Justice delivered a speech at the Opening Ceremony of the 25th Anniversary Scientific Kingdom, visited the Hong Kong Judiciary. Professor Beatson gave a talk on “Human Rights Meeting of the Hong Kong College of Family Physicians Four Years on: the British Experience”. -

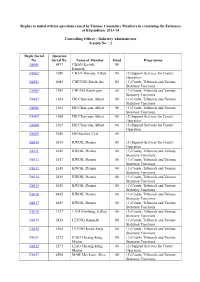

Judiciary Administrator Session No

Replies to initial written questions raised by Finance Committee Members in examining the Estimates of Expenditure 2013-14 Controlling Officer : Judiciary Administrator Session No. : 2 Reply Serial Question No. Serial No. Name of Member Head Programme JA001 4877 CHAN Ka-lok, 80 Kenneth JA002 1699 CHAN Wai-yip, Albert 80 (2) Support Services for Courts' Operation JA003 4083 CHEUNG Kwok-che 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA004 1299 CHUNG Kwok-pan 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA005 1364 HO Chun-yan, Albert 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA006 1365 HO Chun-yan, Albert 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA007 1368 HO Chun-yan, Albert 80 (2) Support Services for Courts' Operation JA008 1369 HO Chun-yan, Albert 80 (2) Support Services for Courts' Operation JA009 3656 HO Sau-lan, Cyd 80 JA010 2615 KWOK, Dennis 80 (2) Support Services for Courts' Operation JA011 2616 KWOK, Dennis 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA012 2617 KWOK, Dennis 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA013 2618 KWOK, Dennis 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA014 2619 KWOK, Dennis 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA015 2620 KWOK, Dennis 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA016 4645 KWOK, Dennis 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA017 4649 KWOK, Dennis 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA018 1127 LAM Kin-fung, Jeffrey 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA019 2434 LEUNG, Kenneth 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA020 2560 LEUNG Kwok-hung 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions JA021 2272 LIAO Cheung-kong, 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Martin Statutory Functions JA022 2273 LIAO Cheung-kong, 80 (2) Support Services for Courts' Martin Operation JA023 4506 MAK Mei-kuen, Alice 80 (1) Courts, Tribunals and Various Statutory Functions Reply Serial Question No. -

V21s CACV 83 2006

(2006-07) VOLUME 21 INLAND REVENUE BOARD OF REVIEW DECISIONS CACV 83/2006 IN THE HIGH COURT OF THE HONG KONG SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION COURT OF APPEAL CIVIL APPEAL NO. 83 OF 2006 (ON APPEAL FROM HCIA NO. 1 OF 2004) ______________ BETWEEN THE COMMISSIONER OF INLAND REVENUE Appellant and COMMON EMPIRE LIMITED Respondent ______________ Before: Hon Rogers VP, Le Pichon JA and Barma J in Court Date of Hearing: 28 November 2006 Date of Judgment: 28 November 2006 Date of Handing Down Reasons for Judgment: 5 December 2006 __________________________ REASONS FOR JUDGMENT __________________________ Hon Rogers VP: (2006-07) VOLUME 21 INLAND REVENUE BOARD OF REVIEW DECISIONS 1. This was an appeal from a Judgment of Deputy High Court Judge To given on 17 January 2006. The matter before the judge was an appeal by way of case stated from the Board of Review. On that occasion the judge dealt with the first and second questions in the case stated. The judge allowed the appeal by the Commissioner. At the conclusion of the hearing of this appeal, this court dismissed the appeal with reasons to be given in writing. The questions arising on this appeal 2. The questions which arise on this appeal have been concisely stated in the amended case stated as follows: “ (1) Whether the Board of Review erred in law in holding that, in the absence of fraud, the assessor had no power to “re-open” a statement of loss issued by an assessor in respect of any particular year of assessment after more than 6 years had elapsed since the expiration or end of that year of assessment? (2) For the purpose of Question (1) above (and without prejudice to the generality thereof), whether [the Board] has erred in law in treating the computation of a Taxpayer’s profit or loss in any particular year as an “assessment” for the purpose of section 60 of [Cap. -

Middle Temple Amity Visit to Singapore

MIDDLE TEMPLE AMITY VISIT TO SINGAPORE 21 TO 23 SEPTEMBER 2016 PART FOUR UK DELEGATION BIOGRAPHIES MIDDLE TEMPLE AMITY VISIT TO SINGAPORE Middle Temple Delegation (Listed alphabetically by surname) Tan Sri Dato’ Cecil Abraham Senior Partner, Cecil Abraham & Partners Cecil Abraham was admitted as an Advocate & Solicitor of the High Court of Malaya and the Supreme Court of Singapore. He graduated from Queen Mary College, University of London (QMUL) with an LL.B. Hons and is a Fellow of QMUL. He is a Barrister-At-Law and also a Bencher of The Middle Temple. Cecil has a very extensive appellate court practice in the Court of Appeal and Federal Court of Malaysia. He has acted as Counsel in many landmark cases. Cecil has appeared in the Privy Council when the Privy Council was the final Court of Appeal in Malaysia in 5 landmark cases. Cecil acts as counsel and arbitrator in investor treaty arbitrations held under the ICSID and UNCITRAL Rules. Mekail Ahmed Esq Mekail Ahmed served on the Hall Committee during his time as President of the MTSA in 2004. He began his legal career with Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton before switching to structuring derivative products with Citigroup. His work as a structurer included a focus on legal and regulatory issues. In 2010 he joined Standard Chartered Bank to build their Equity and Fund Derivatives business. Mekail has been resident in Hong Kong since 2007. His sporting interests include squash, hockey and boxing. The Honourable Mr Justice Barma JA Justice of Appeal of the Court of Appeal of the High Court (HK) Mr Justice Aarif Barma read law at Oxford, where he obtained his BA and BCL, and was then called to the Bar by the Middle Temple in 1983.