An Exploration of Business Location Changes Accompanying Commuter Rail Development in Denton, Texas." Papers in Applied Geography 36 (2013): 218- 89

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Dallas Cowboys Training Camp Promo

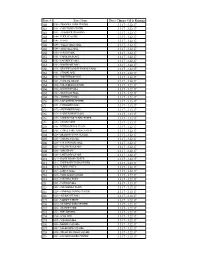

Training Camp Store Allocations Store Number Name Address 2685 The Parks Mall 3851 S Cooper St 2795 Stonebriar Mall 2607 Preston Rd 2434 Coronado Center 6600 Menaul Blvd NE Ste 3000 2939 North Star Mall 7400 San Pedro Ave 226 La Plaza 2200 S 10th St 2904 Southpark Meadows S/C 9500 S IH-35 Ste H 631 Ingram Park Mall 6301 NW Loop 410 702 Cielo Vista Mall 8401 Gateway Blvd W 1330 La Palmera Mall 5488 S Padre Island Dr Ste 4000 179 Timber Creek Crossing 6051 Skillman St 2946 Plaza at Rockwall 1015 E I 30 2877 The Rim Shopping Center 17710 La Cantera Pkwy 2338 Town East Mall 6000 Town East Mall 2055 Collin Creek Mall 821 N Central Expwy 1046 Golden Triangle Mall 2201 S Interstate 35 E Ste D 2410 Vista Ridge Mall 2401 S Stemmons Fwy Ste 4000 2884 Tech Ridge Center 12351 N IH-35 2826 Cedar Hill Village 333 N Hwy 67 2960 El Mercado Plaza 1950 Joe Battle Blvd 2969 Sherman Town Center 610 Graham Dr 2934 University Oaks Shopping Center 151 University Oaks 993 South Park Mall 2418 SW Military Dr 2982 Village at Fairview 301 Stacy Rd 2921 Robertsons Creek 5751 Long Prairie Rd 2105 Crossroads Mall 6834 Wesley St Ste C 1943 North East Mall 1101 Melbourne Dr Ste 5000 1419 Ridgmar Mall 1900 Green Oaks Rd 2093 Mesilla Valley Mall 700 Telshor Blvd Ste 2000 2021 Richland Mall 6001 W Waco Dr 579 Music City Mall 4101 E 42nd St 485 Mall of Abilene 4310 Buffalo Gap Rd 2682 Penn Square Mall 1901 NW Expwy Ste 1200 2833 Rolling Oaks Mall 6909 N Loop 1604 E 2806 Sunrise Mall 2370 N Expwy Ste 2000 712 Sikes Senter Mall 3111 Midwestern Pkwy 996 Broadway Square Mall 4401 S Broadway 450 Rio West Mall 1300 W Maloney Ave Ste A 1749 Central Mall 2400 Richmond Rd Ste 61 2905 Alliance Town Center 3001 Texas Sage Trl 658 Mall De Norte S/C 5300 San Dario 1989 Sunset Mall 6000 Sunset Mall 259 Colonial/Temple Mall 3111 S 31st St Ste 3301 1101 Valley Crossing Shopping Center 715 E Expressway 83 2036 Midland Park Mall 4511 N Midkiff Rd 304 Longview Mall 3550 McCann Rd 2110 Killeen Mall 2100 S W.S. -

Retail | & Incentives Costs

COSTS & INCENTIVES | REAL ESTATE - RETAIL COSTS & INCENTIVES Real Esate - DFW Retail Centers: 7 Retail Far North 24 Opportunities at Dallas 23 19 The Dallas-Fort Worth building market 3 | was the second biggest in 2019 after 8 RETAIL REAL ESTATE New York City with almost $22.5 billion in Every Intersection construction, the fourth year in a row that Lewisville/Denton Richardson/Plano new construction topped $20 billion. By 22 Largest Retail Centers 4 the end of 2019, according to CBRE, DFW 27 retail construction had increased 10 percent 1 Alliance Town Center 15 Plaza Central quarter-over-quarter, with many new large- 9 5 scale starts leading the trend. Most of this LBJ Freeway 2 Arlington Highlands 16 Ridgmar Mall 17 activity is concentrated in the northern Las Colinas 6 3 Centre at Preston Ridge 17 Southlake Town Square suburbs with North Central Dallas and Far 1 Central Preston North Dallas accounting for 45 percent of 4 Collin Creek Mall 18 RedBird Expressway new construction. North Center 21 5 Firewheel Town Center 19 Stonebriar Centre Fort Worth East Dallas 11 14 6 Galleria 20 The Parks at Arlington Northeast 13 Stemmons Fort Worth 25 Mid-Cities Freeway 7 Golden Triangle Mall 21 The Shops at Park Lane Dallas CBD Live, Work, and Play 8 Grandscape 22 The Shops at Willow Bend Fort Worth CBD 28 15 The development of higher density, mixed- 9 Grapevine Mills Mall 23 The Villages at Allen 16 Southwest Dallas use centers o ers unique opportunities to 10 Hulen Mall 24 The Villages at Fairview South both businesses and residents of the Dallas– Fort Worth 12 20 Fort Worth region. -

NCTC SHUTTLE Eulene Brock Downtown Denton Transit Center

NCTC SHUTTLE NCTC SHUTTLE NCTC MedPark City Hall Colorado Blvd. NCTC SHUTTLE NCTC East Mayhill WE Woodrow Ln. Denton Regional S Medical Center Dallas Dr. Loop 288 Mayhill Hospital Fred Moore 35E DENTON Park Integrity Denton Transitional Hospital Housing Authority Mayhill Rd. Mayhill EULENE BROCK DOWNTOWN MEDPARK STATION DENTON TRANSIT CENTER Lillian Miller Lillian B Robinson Rd. Corinth St. Corinth B North Central CORINTH Texas College Walton Dr. Garden Ridge Blvd. Atrium Medical Shady Shores Rd. Shores Shady Center of Corinth Eagle Point Rd. Post Oak Rd. Post 35E Lewisville McGee Ln. Corinth Pkwy. 35E Swisher Rd. Teasley Dr. Lake Park 35E HIGHLAND VILLAGE NCTC – CORINTH CAMPUS HIGHLAND VILLAGE /LEWISVILLE LAKE Justin Road Timber Creek Rd. Main Garden Ridge Garden McGee Valley Ridge Summit Lewisville Lake Ln. Kirkpatrick 35E Valley Pkwy Flower Mound Performing Cross Timbers Rd. Arts Center Rustic College Pkwy D Timbers Park Justin Rd. Civic Circle Luther FM Main 407 Summit Ave. Rustic Timbers Ln. Lewisville High School C Valley Ridge Morriss Rd. Morriss SUMMIT & CIVIC – LEWISVILLE NCTC – FLOWER MOUND CAMPUS FLOWER MOUND 35E College Pkwy. Rd. Ridge Garden C Eulene Brock Downtown Denton Transit Center (DDTC) D Cross Timbers Rd. Main St. Served by NCTC Shuttle, all Denton Connect bus routes and A-train LEWISVILLE MedPark Station LEGEND Served by NCTC Shuttle, Connect Route 2, UNT Shuttle Colorado Express and A-train Shuttle Stop Eulene Brock Downtown Denton Transit Center (DDTC) Highland Village/Lewisville Lake Station (HV/LL) MedPark Station Served by NCTC Shuttle, Connect RSVP and A-train Highland Village/Lewisville Lake Station (HV/LL) NCTC North Shuttle Route Civic & Summit NCTC South Shuttle Route Served by NCTC Shuttle, all Lewisville Connect bus routes and Connect RSVP 70 Effective 1-19-15 71 NCTC Shuttle (North Central Texas College) Serves Corinth and Flower Mound campuses with connectivity between NCTC Shuttle Denton and Lewisville. -

Real Estate – Retail

COSTS & INCENTIVES | REAL ESTATE - RETAIL COSTS & INCENTIVES Real Esate - DFW Retail Centers: 7 Retail Far North 24 Opportunities at Dallas 23 19 The Dallas-Fort Worth retail real estate 3 | market ended the year with 91.7 percent 8 - RETAIL REAL ESTATE occupancy despite the economic downturn Every Intersection in 2020, the eighth consecutive year of Lewisville/Denton Richardson/Plano occupancy above 90 percent. 1.7 million 22 Largest Retail Centers 4 square feed of new construction was added 27 in 2020, down only slightly from 1.8 million 1 Alliance Town Center 15 Plaza Central in 2019. Most of this activity is concentrated 9 5 in the northern suburbs with North Central LBJ Freeway 2 Arlington Highlands 16 Ridgmar Mall 17 Dallas and Far North Dallas accounting for Las Colinas 6 3 Centre at Preston Ridge 17 Southlake Town Square 45 percent of new construction. 1 Central Preston 4 Collin Creek Mall 18 Southwest Center Mall Expressway North Center 21 5 Firewheel Town Center 19 Stonebriar Centre Fort Worth East Dallas 11 14 6 Galleria 20 The Parks At Arlington Northeast 13 Stemmons Fort Worth 25 Mid-Cities Freeway 7 Golden Triangle Mall 21 The Shops At Park Lane Dallas CBD Live, Work, and Play 8 Grandscape 22 The Shops At Willow Bend Fort Worth CBD 28 15 The development of higher density, mixed- 9 Grapevine Mills Mall 23 The Villages At Allen 16 Southwest Dallas use centers offers unique opportunities to 10 Hulen Mall 24 The Villages At Fairview South both businesses and residents of the Dallas– Fort Worth 12 20 2 Fort Worth region. -

Fiscal Year 2012-13 Brought Exciting News in Economic Development

City of Denton Comprehensive Annual Financial Report Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 2013 Denton, Texas Denton Municipal Electric’s Engineering and Operations Building VISION “Destination Denton” Denton is an identifiable and memorable destination and a community of opportunities. We achieve this by providing high quality of life through excellence in education, entertainment, and employment; neighborhood vitality and sustainability; environmental and financial stewardship; and superior public facilities and services. MISSION “Dedicated to Quality Service” The City of Denton will foster an environment that will deliver extraordinary quality service and products through stakeholder, peer group, and citizen collaboration; leadership and innovation; and sustainable and efficient use of resources. VALUES “We Care” We care about our people, our community, and our work. We do this with integrity, respect, and fairness. + CITY OF DENTON, TEXAS COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT For the fiscal year ended September 30, 2013 CITY MANAGER George C. Campbell ASSISTANT CITY MANAGER AND CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER Bryan Langley Prepared by: Chuck Springer Director of Finance Antonio Puente Harvey Jarvis Assistant Director of Finance Controller Kevin Ann Mullen, CPA Cody Wood Assistant Controller Assistant Controller David Wilson Diane Chang, CPA Electric Accounting Manager Senior Grants Accountant Kurt Breyfogle Randall Mahaffey, CIA Senior Utilities Accountant Senior Accountant Ed Lane, CPA Cindy Liang, CPA Accountant III Accountant III Lori Allen -

Paloma Creek Community

YOUR Community Community Information 17 16 15 380 Homeowner’s 18 Paloma Creek Association HOA: $335 Annually Panther Creek Pkwy 289 Premier Series Cap Fee: $100 Transfer Fee: $100 Eldorado FM 720 13 Parkway School District Main Street 14 Paloma Creek Elementary School 9 1600 Navo Road Lewisville Lake (972) 347-7300 Toll Bridge Road Preston Navo Middle School Teel Pkwy Teel 11 1707 Navo Road Lebanon Rd. (972) 347-7500 12 Denton High School 1007 Fulton Street (972) 369-2000 FM 423 City Taxes 35E TOTAL: 2.46 121 Per $100 10 Assessed Value North Dallas Tollway Paloma Creek Schools Shopping Recreation Hospitals/Clinics 1 | Paloma Creek Elementary 4 | Stonebriar Centre 9 | Cinemark Cinema 17 | Denton Regional Medical 2 | Navo Middle School 5 | Frisco Square 10 | DFW Airport Center 3 | Denton High School 6 | Golden Triangle Mall 11 | Dr Pepper Arena 18 | Denton Community Hospital 7 | Kroger 12 | Dr Pepper Ballpark 8 | Walmart SuperCenter 13 | Trails of Frisco Golf Club 14 | Main Event 15 | Texas Women’s University 16 | University of North Texas 214.872.7080 | 1601 Flamingo Drive | Little Elm, TX 75068 © 2016 Gehan Homes. All rights reserved. Association Fees, Schools and Taxes are estimates only and are subject to change. See local taxing authorities and ISD for most current information. All Items shown are an artist’s rendering regarding planned community designs and amenities and are subject to change without notice. gehanhomes.com Paloma Creek 02.02.16 YOUR Home YOUR Neighborhood Standard Features Life at Paloma Creek Exterior Design Gourmet Lifestyle Kitchen This beautiful Paloma Creek community is conveniently located near Stonebriar Center, Downtown · High-quality American-made Clay Brick · Granite Countertops with 12” Ceramic Tile Backsplash McKinney and Denton. -

Digital-ATC-Leasing-Deck-11.2019-1

welcome Alliance Town Center is located at Interstate 35W and Heritage Trace Parkway in North Fort Worth, just west of Keller, Texas. The 1 million square-foot center is anchored by Belk, JCPenney, Total Wine, Cinemark, Dick’s Sporting Goods, Best Buy, Havertys, DSW, PetSmart, Boot Barn, Kroger and many more. property overview Alliance Town Center, a joint venture with Hillwood and Invesco, is part of the 26,000-acre Alliance Texas Development. • Fort Worth Alliance Airport • 44 million+ SF developed • Industrial space: 7,000+ acres • Office space: 800 acres • Residential: 10,000+ single family homes/ 5,000 multi-family units • 73 acre HCA medical campus • 488+ corporate residents including Amazon, Facebook, General Electric, Fidelity and BNSF Railway • 50,000+ employees • Anchored by modal inland port Alliance Global Logistics hub • 65 listed on Fortune 500, Global 500, or Forbes’ Top List of Private Firms • Population of 2 million within 20 miles of Fort Worth Alliance Airport Golden Triangle Mall Allen Premium Outlets The Village at Fairview Stonebriar Centre The Shops at Legacy Plano Lewisville Flower Mound The Shops at Willow Bend Collin Creek Mall Vista Ridge Mall Grapevine Mills Carrollton Richardson Village on the Parkway Firewheel Town Center Southlake Town Square Garland Preston Oaks NEW MAP NorthPark Center The Shops at Park Lane North Richland Hills Irving Inwood VIllage Irving Mall Highland Park VIllage North East Mall Fort Worth Dallas Montgomery Plaza Mesquite Ridgmar Mall West 7th Arlington University Park Village Grand Prairie Hulen Mall The Parks at Arlington Arlington Highlands Grand Prairie Premium Outlets 5000 South Hulen GREATER DFW RETAIL MAP • 4th largest MSA in the U.S. -

Document Navigation Instructions 1

Document Navigation Instructions 1. To navigate directly to a specific category of questions, click anywhere in the line within the Table of Contents containing the category you wish to view. 2. To search for a term or phrase within the document, use keystroke “Ctrl + F” to Find, or select Edit > Find from the menu bar. There may also be a magnifying glass icon available to select for this purpose, depending on the version of Adobe being used to view the document. As of Tuesday, 3/24/20 Table of Contents Document Navigation Instructions ............................................................................................................... 1 COVID-19 Questions ..................................................................................................................................... 3 City/County STAY AT HOME Orders ...................................................................................................... 3 Business Updates .................................................................................................................................. 3 County Health ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Testing Information .............................................................................................................................. 4 Various Operations Information ........................................................................................................... 4 Meetings, Voting, and -

Store # Store Name Dates Clinique Gift Is Running 140 3.3.17

Store # Store Name Dates Clinique Gift Is Running 140 0140 - TRIANGLE TOWN CENTER 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 141 0141 - CARY TOWN CENTER 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 143 0143 - ALAMANCE CROSSING 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 144 0144 - FOUR SEASONS 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 145 0145 - HANES 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 146 0146 - VALLEY HILLS MALL 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 148 0148 - ASHEVILLE MALL 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 150 0150 - SOUTH PARK 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 151 0151 - CAROLINA PLACE 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 152 0152 - EASTRIDGE MALL 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 153 0153 - NORTHLAKE MALL 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 156 0156 - WESTFIELD INDEPENDENCE MALL 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 161 0161 - CITADEL MALL 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 162 0162 - NORTHWOOD MALL 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 163 0163 - COASTAL GRAND 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 164 0164 - COLUMBIANA CENTRE 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 166 0166 - HAYWOOD MALL 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 167 0167 - WESTGATE MALL 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 168 0168 - ANDERSON MALL 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 170 0170 - MACARTHUR CENTER 3.3.17 - 3.13.17 171 0171 - LYNNHAVEN MALL 3.3.17 - 3.13.17 172 0172 - GREENBRIER MALL 3.3.17 - 3.13.17 174 0174 - PATRICK HENRY MALL 3.3.17 - 3.13.17 176 0176 - SHORT PUMP TOWN CENTER 3.3.17 - 3.13.17 179 0179 - STONY POINT 3.3.17 - 3.13.17 201 0201 - INTERNATIONAL PLAZA 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 203 0203 - CITRUS PARK TOWN CENTER 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 204 0204 - BRANDON TOWN CENTER 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 205 0205 - TYRONE SQUARE 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 206 0206 - COUNTRYSIDE MALL 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 207 0207 - GULFVIEW SQUARE 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 208 0208 - WIREGRASS 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 209 0209 - LAKELAND SQUARE 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 210 0210 - EAGLE RIDGE CENTER 3.3.17 - 3.22.17 213 0213 -

Voices Is the Official Well Today Is the Very Best Day to Take Charge of Meaningful to You

VOLUME 4, ISSUE 1 JULY 2006 V O I C E S D I S T R C 2 5 Earl Hill, DTM• District Governor 2006-2007 T O A S M E R Seven Keys to Reaching for Success this year Earl Hill, DTM - District 25 Governor 2006-2007 Ever have those days when no matter what we 5. Visualize and write try, life seems to be a series of one step forward down how you desire to and two steps back? live successfully - think of the things that are Voices is the official Well today is the very best day to take charge of meaningful to you. publication of District 25, your life and develop strategies to achieve Things that give you serving Toastmasters personal success. We will need to work hard and pleasure, comfort, and throughout North Central make a commitment to our personal success fulfillment. Then being Texas. plan, but once we break the inertia we will find as specific as possible, write down how you that small achievements will help us gain want to live. Don't listen to any of the Inside this issue: momentum, and each step forward will negative, just concentrate. Write down every Are you getting all you can 2 attract more success. detail, where you live, what your house is like get out of Toastmasters? down to the decor. What you and your friends 1. Take a look at the one and only person are passionate about, what kinds of District Leadership Summit 2 responsible for your success - YOU. To be community projects do you donate your time and Staff Training successful you must take complete responsibility and money to. -

Dillard's Store Name: Wacoal Fi(Gh)T for the Cure ™

Wacoal Fi(gh)t for the Cure ™ Help Knockout Breast Cancer at a Fit for the Cure ® Event. Event Dillard's Store Name: City: State: Event Date: Hours: Parkway Place Huntsville AL 10/11/12 10-8 Eastern Shore Center Spanish Fort AL 10/5/12 10-8 Bel Air Mall Mobile AL 10/6/12 10-8 Wiregrass Commons Dothan AL 10/5/12 10-8 Quintard Mall Oxford AL 10/2/12 10-8 Village Mall Auburn AL 10/5/12 10-8 The Shoppes at Eastchase Montgomery AL 10/4/12 10-8 Regency Square Mall Florence AL 10/5/12 10-8 Park Plaza Little Rock AR 10/5/12 10-8 Hot Springs Mall Hot Springs AR 10/5/12 10-8 Northwest Arkansas Fayetteville AR 9/20/12 10-8 Pines Mall Pine Bluff AR 10/5/12 10-8 The Mall @ Turtle Creek Jonesboro AR 10/5/12 10-8 McCain Mall N. Little Rock AR 10/5/12 10-8 Pinnacle Hills Promenade Rogers AR 9/19/12 10-8 Central Mall Ft. Smith AR 9/21/12 10-8 Scottsdale Scottsdale AZ 10/26/12 10-8 Paradise Valley Phoenix AZ 10/25/12 10-8 Park Place Tucson AZ 10/18/12 10-8 Westridge/Desert Sky Mall Phoenix AZ 10/5/12 10-8 Arrowhead Towne Center Glendale AZ 10/19/12 10-8 Chandler Fashion Mall Chandler AZ 10/20/12 10-8 Superstition Mall Mesa AZ 10/5/12 10-8 San Tan Village Gilbert AZ 10/5/12 10-8 Prescott Gateway Prescott AZ 10/5/12 10-8 The Shops at Lake Havas Lake Havasu AZ 10/5/12 10-8 Tucson Mall Tucson AZ 10/17/12 10-8 Flagstaff Flagstaff AZ 10/5/12 10-8 Promenade At Casa Grande Casa Grande AZ 10/5/12 10-8 Yuma Palms Yuma AZ 10/4/12 10-8 Sierra Vista Towne Ctr. -

CITY of DENTON CITY COUNCIL MINUTES May 2, 2017

CITY OF DENTON CITY COUNCIL MINUTES May 2, 2017 After determining that a quorum was present, the City Council convened in a Work Session on Tuesday, May 2, 2017 at 2:00 p.m. in the Council Work Session Room at City Hall. PRESENT: Mayor Pro Tem Roden, Council Member Wazny, Council Member Briggs, Council Member Hawkins, Council Member Gregory, Council Member Bagheri, and Mayor Watts. ABSENT: None. 1. Citizen Comments on Consent Agenda Items Willie Hudspeth requested that Consent Agenda items C, E and F be pulled and whether minority contractors were considered. He spoke off topic regarding Work Session C in opposition to the prior practice of not allowing African Americans to be buried in IOOF Cemetery. 2. Requests for clarification of agenda items listed on the agenda for May 2, 2017. Staff responded to Council’s requests for clarification of the following items: Council Member Briggs requested that Consent Items A, F, and H be pulled for separate consideration. Council Member Bagheri requested that Consent Items C and E be pulled for separate consideration. Council Member Gregory requested staff presentations for C, E, F and H. City Manager Hileman noted that Executive Session 1A and Consent Agenda 4A would not be considered. An alternative ordinance was presented for 5C. 3. Work Session Reports A. ID 17-517 Receive a report, hold a discussion and provide staff direction regarding the creation of a small area plan and implementation strategy. Munal Mauladad, Director of Development Services, stated that the Council adopted the Denton Plan 2030 in 2015. The Denton Plan 2030 provided policy direction for land use and development patterns.