Love We Remember the SACRIFICE on Good Friday. We Celebrate the VICTORY on Easter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mark Summers Sunblock Sunburst Sundance

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 11 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. SUNFREAKZ Belgian male producer (Tim Janssens) MARK SUMMERS 28 Jul 07 Counting Down The Days (Sunfreakz featuring Andrea Britton) 37 3 British male producer and record label executive. Formerly half of JT Playaz, he also had a hit a Souvlaki and recorded under numerous other pseudonyms Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 3 26 Jan 91 Summers Magic 27 6 SUNKIDS FEATURING CHANCE 15 Feb 97 Inferno (Souvlaki) 24 3 13 Nov 99 Rescue Me 50 2 08 Aug 98 My Time (Souvlaki) 63 1 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 2 Total Hits : 3 Total Weeks : 10 SUNNY SUNBLOCK 30 Mar 74 Doctor's Orders 7 10 21 Jan 06 I'll Be Ready 4 11 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 10 20 May 06 The First Time (Sunblock featuring Robin Beck) 9 9 28 Apr 07 Baby Baby (Sunblock featuring Sandy) 16 6 SUNSCREEM Total Hits : 3 Total Weeks : 26 29 Feb 92 Pressure 60 2 18 Jul 92 Love U More 23 6 SUNBURST See Matt Darey 17 Oct 92 Perfect Motion 18 5 09 Jan 93 Broken English 13 5 SUNDANCE 27 Mar 93 Pressure US 19 5 08 Nov 97 Sundance 33 2 A remake of "Pressure" 10 Jan 98 Welcome To The Future (Shimmon & Woolfson) 69 1 02 Sep 95 When 47 2 03 Oct 98 Sundance '98 37 2 18 Nov 95 Exodus 40 2 27 Feb 99 The Living Dream 56 1 20 Jan 96 White Skies 25 3 05 Feb 00 Won't Let This Feeling Go 40 2 23 Mar 96 Secrets 36 2 Total Hits : 5 Total Weeks : 8 06 Sep 97 Catch Me (I'm Falling) 55 1 20 Oct 01 Pleaase Save Me (Sunscreem -

Schiller's Jungfrau, Euripides's Iphigenia Plays, and Joan of Arc on the Stage

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2015 Sisters in Sublime Sanctity: Schiller's Jungfrau, Euripides's Iphigenia Plays, and Joan of Arc on the Stage John Martin Pendergast Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1090 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SISTERS IN SUBLIME SANCTITY: Schiller’s Jungfrau, Euripides’s Iphigenia Plays, and Joan of Arc on the Stage by John Pendergast A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The City University of New York 2015 ii © 2015 JOHN PENDERGAST All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature to satisfy the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 21 May 2015 Dr. Paul Oppenheimer________________________ Date Chair of the Examining Committee 21 May 2015______________ Dr. Giancarlo Lombardi ______________________ Date Executive Officer Dr. Paul Oppenheimer Dr. Elizabeth Beaujour Dr. André Aciman Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Abstract Sisters in Sublime Sanctity: Schiller’s Jungfrau, Euripides’s Iphigenia Plays, and Joan of Arc on the Stage by John Pendergast Adviser: Professor Paul Oppenheimer At the dawn of the nineteenth century, Friedrich Schiller reinvented the image of Joan of Arc in his play, Die Jungfrau von Orleans, with consequences that affected theatrical representations of Joan for the rest of that century and well into the twentieth. -

The Euthyphro

1 (portion of) T H E E U T H Y P H R O By Plato Written 380 B.C. Persons of the Dialogue S O C R A T E S E U T H Y P H R O Scene The Porch of the Archon. ------------------------------------------------------------------------ Note on ‘holiness’, by the translator: The term ‘holy’ translates the Greek term ‘hosion’, which means something like ‘required by religion’ or ‘permitted by religion’, but which was also very widely used as a term of commendation that was felt to have independent ethical content. The English word ‘sin’ is a good paralel for this kind of word. ‘Sin’ has strong religious connotations; it is a term hardly used at all by non-religious people; yet everyone can easily understand the claim that ‘to do such and such would be a sin’ — whether they hold any religious views or not. The word has a perfectly clear ethical implication. ‘Hosion’ works in the same way, but as a positive rather than negative term, meaning something like ‘in accordance with religion’ but also ‘morally right’. Almost all terms of religiously-grounded ethical approval or disapproval, in all cultures, acquire this dual role as terms with ethical content and religious content. Religious terminology, whatever else it does, expresses ethical ideas, and always has done (and always will) entirely regardless of whether the cosmological and theological beliefs behind it are true, or false. It is exactly that feature, that mixing of ethical and religious thought that is the subject of the dialogue. The dialogue asks this central question: How can any concept -

Thoughts on Spiritual Gifts Pastor Charlie Handren Spring 2010

THOUGHTS ON SPIRITUAL GIFTS PASTOR CHARLIE HANDREN SPRING 2010 CONTENTS: 1. Lexical Definitions: Page 1 2. Notes on Various Relevant Texts: Page 2 3. Notes on Romans 12:3-8: Page 4 4. Notes on Ephesians 4:1-16: Page 8 5. Notes on 1 Corinthians 12 – 14: Page 14 6. Appendix One: Summary Chart of the Key Terms in Eph 4:11: Page 23 LEXICAL DEFINITIONS: Working Definition: A spiritual gift is a supernatural enabling that derives from the indwelling presence of the Holy Spirit, given to every born-again believer, for the glory of God, the building up of the body of Christ, and the joy of the soul. (pneumatikos): derives from (pneuma, i.e., spirit)—one who is spiritual; that which is of or from the Spirit (sometimes used as a substantive so that words like “gifts, blessings, or things” are implied). (charisma): derives from (charis, i.e., grace or gift)—a gift or favor which is given freely, generously, and graciously. 1 NOTES ON VARIOUS RELEVANT TEXTS: Romans 1:11-12 Though they ultimately derive from the Spirit, spiritual gifts can be imparted from one believer to another. The purpose of impartation is mutual encouragement, that is, the building up of the body, and the means of impartation is faith. That is, as one walks in the Spirit by faith, the Spirit gifts that one so that he can share with others and build them up in their faith. I cannot grant the gift of tongues, but if I share a key insight that the Spirit has given me through the Scripture I am “imparting some spiritual gift” to another. -

God Is Loving 1 John 4:7-10

1 GOD LOVES 1 JOHN 4:7-10; ROMANS 5:6-10 Frederick Douglass grew up as a slave in Maryland in the early nineteenth century. He escaped and became a leading abolitionist who fought to end slavery forever. He and his mother were separated when he was but an infant. It was a common custom for slave owners to part children from their mothers at a very early age. Her new home was about 12 miles from her son’s home. Nonetheless, young Frederick's mother several times found ways to see her son. She made her journeys to see him at night, traveling the whole distance on foot, after the performance of her day's work. She was a field hand, and a whipping was the penalty of not being in the field at sunrise. She would spend as much of the night with her son as possible. She would lie down with him and get him to sleep, but long before he woke up she was gone. Imagine the power of a mother's love! Frederick Douglass' mother worked all day long in the scorching heat of the tobacco fields, and then, when her body was crying for rest, she walked 12 miles in the dark to see her son. After comforting him and holding him as he fell asleep, she had to walk another 12 miles back. She gave up a night's sleep. She risked getting a severe whipping if she were discovered, or if she got home late. But nothing could keep this mother from her son. -

Aftab Alam - Poems

Poetry Series Aftab Alam - poems - Publication Date: 2015 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Aftab Alam(15 th April 1967) [Died on 30th June 2015 in Apollo hospital Ranchi at 1: 25 am due to brain hemorrhage occurred on 19th march 2015 at Dehradun while returning from the office around 6 pm followed by coma, no recovery till the last breadth.] I thank, all those who read and comment Through FB or PH, they pause a moment Precious time steal and spent on charity Filling life hole of hollowness with sanity Gratitude to all poets at open rendezvous The POEM HUNTER Learn to laugh in grief..It is my request in brief Aftab Alam 'Khursheed' AFTAB ALAM is an Indian poet born at Ranchi Capital of Jharkhand on 15 April 1967(Saturday) in the house of Md. Sanaullah (Father) and: Qaisra Khatoon(Mother) ( married in the year 1989 with Aziz Fatima her nickname was Bahar(spring) She was brave and beautiful, blessed with three children ta Aftab 2. Pardaz Aftab and 3) Sheikh Aghaz Aftab. She died in a road accident at Ranchi on 29th Oct 2007 buried at the cemetery of Prastoli on Monday at night on the same day after the night prayer, Hobby: To read the books of any kind but Quran is above Byron, William Wordsworth, Maxim Gorky, Prem chand, Nirala, Iqbal, Dushyant, Dumil, Charles Dicken, Leo Tolstoy… Keats kills makes him to cool, Charles Dicken, prem chand and Maxim Gorky Shown the path to write and understand what is the world. A lover of Nature and its creatures, 'HOW LONG PEACE WILL KILL THE PEACE LOVING PEOPLE' Address: S/o Md Sanaullah (Near Mosque) , Prastoli, PS/PO Doranda, RANCHI Jharkhand(India) PIN 834002mobile no. -

God Is Love 1 John 4:7–12 INTRODUCTION “What Is Love

God is Love 1 John 4:7–12 INTRODUCTION “What is love?” That’s the question a British newspaper was asking in an article I read several years back. The writer of the article garnered opinions from those whom they considered to be experts. They asked a physicist. His answer was that love is basically chemistry, and we really have no control over it because we’re talking about the release of chemicals such as pheromones and dopamine. Not only that, love is a survival tool that we have evolved over time to promote long-term relationships. They asked a psychotherapist. Her answer was that love is a variety of emotions—sexual, non- sexual, brotherly—but that we must not forget self-love, because unless you love yourself, you can’t love others. They asked a writer of romance novels. Unsurprisingly, she couldn’t really define love. After all, from her vantage point, it depends on your situation. But one thing is certain, it’s the emotion that drives all great stories. Is love chemistry? Is love emotions? Is love the undefined driver of good novels? What is love? We use the word love in a variety of ways. We use the word love to refer to just about everything and anything. We use love in reference to what we cherish most: “I love God.” “I love my family.” But we also use the word love to regularly refer to things that are of lesser value. My wife made an apple pie the other day, and halfway through the first piece I said, “I love apple pie.” So, what is love? We’ve been talking about the attributes of God since mid-February. -

Twentieth Week in Ordinary Time Tuesday, August 18, 2015

“What page, what passage of the inspired books of the Old and New Testaments is not the truest of guides for human life?” ~Saint Benedict, from the Rule of Saint Benedict (73:3) “There are those who seek knowledge for the sake of knowledge; that is Curiosity. There are those who seek knowledge to be known by others; that is Vanity. There are those who seek knowledge in order to serve; that is Love.” ~SAINT BERNARD OF CLAIRVAUX Monday, August 17, 2015 ~ Twentieth Week in Ordinary Time Holy Gospel: Matthew 19:16-22 A young man approached Jesus and said, “Teacher, what good must I do to gain eternal life?” He answered him, “Why do you ask me about the good? There is only One who is good. If you wish to enter into life, keep the commandments.” He asked him, “Which ones?” And Jesus replied, “You shall not kill; you shall not commit adultery; you shall not steal; you shall not bear false witness; honor your father and your mother; and you shall love your neighbor as yourself.” The young man said to him, “All of these I have observed. What do I still lack?” Jesus said to him, “If you wish to be perfect, go, sell what you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come, follow me.” When the young man heard this statement, he went away sad, for he had many possessions. Meditation: The young man who apparently had the best the world could offer – money, property, a position in society – came to Jesus because lacked one thing. -

Rhythm & Blues...37 Pricelist/Preisliste...96

1 COUNTRY .......................2 POP.............................57 AMERICANA/ROOTS/ALT. .............14 POP INSTRUMENTAL .................63 OUTLAWS/SINGER-SONGWRITER .......15 LATIN ............................65 WESTERN..........................17 JAZZ .............................65 C&W SOUNDTRACKS.................18 SOUNDTRACKS .....................66 C&W SPECIAL COLLECTIONS...........19 COUNTRY AUSTRALIA/NEW ZEALAND....19 DEUTSCHE OLDIES ..............66 COUNTRY DEUTSCHLAND/EUROPE......19 KLEINKUNST / KABARETT ..............70 BLUEGRASS ........................20 INSTRUMENTAL .....................22 BOOKS/BÜCHER ................71 OLDTIME ..........................23 CHARTS ..........................77 CAJUN/ZYDECO ....................23 TEXMEX ...........................24 DVD ............................77 FOLK .............................24 VINYL...........................84 ROCK & ROLL ...................26 LABEL R&R .........................33 ARTIST INDEX...................88 R&R SOUNDTRACKS .................35 ORDER TERMS/VERSANDBEDINGUNGEN..95 ELVIS .............................36 PRICELIST/PREISLISTE ...........96 RHYTHM & BLUES...............37 GOSPEL ...........................39 BEAR TIPs .......................38 SOUL.............................40 VOCAL GROUPS ....................42 LABEL DOO WOP....................43 BEAT, 60s/70s ..................44 SURF .............................49 REVIVAL/NEO ROCKABILLY ............51 BRITISH R&R ........................54 INSTRUMENTAL R&R/BEAT .............55 BEAR FAMILY -

Because Iniquity Shall Abound, the Love of Many Shall Wax Cold: Matthew 24:12

Because iniquity shall abound, the love of many shall wax cold: Matthew 24:12 M.Sci. Dmitri Martila, Tartu University, [email protected] The aim of this article is to fix atheists (they are willingly disabled; they have cut off not a limb, but the Religion with its Truth and Love), and to improve (if it is possible) the theism of theists. Two questions that say everything about a person: How many friends do you have? Is there love at first sight? Here I have a scientific article that love always happens at first sight, although couples don’t perceive it that way. Keywords: Love, Love at first sight, ethics, morality, science, solipsism. To Atheist-readers: short reminder of their hated God: "Existent God" or "non-existent idol". Google words "God", "idol", "existence". YOU CAN NOT LEAVE a THEISM. Even you are born and structured with it. It can not be removed from your blood: Brooks, M., Natural born believers, New Scientist 201(2694):31–33, 7 February 2009; Beckford, M., Children are born believers in God, academic claims—Children are born believers in God and do not simply acquire religious beliefs through indoctrination, according to an academic, The Telegraph, 24 November 2008. The atheism is the basic false theism, the founder and the first atheist is satan himself. The atheism is different from True Theism by absence of Love. Love and Respect to a stranger. Spirit of Love is God. Disbelievers think of Love as poison in their blood. Thus, it is the mental case: "Alice Cooper - Poison" https://youtu.be/Qq4j1LtCdww Why all theists say that "God dislikes proofs" when the Eastern Orthodox Christians shout in the temple: "Christ is Risen!"? This is the shortest proof of Christ and His Church. -

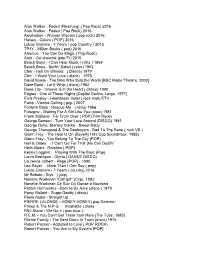

(Restrung) ( Pop Rock) 2016 Alan Walker

Alan Walker - Faded (Restrung) ( Pop Rock) 2016 Alan Walker - Faded ( Pop Rock) 2016 Awolnation - Woman Woman ( pop rock) 2016 Halsey - Colors ( POP) 2016 Lukas Graham - 7 Years ( pop Country ) 2015 TP4Y - Million Bucks ( pop) 2016 America - You Can Do Magic ( Pop Rock) Amir - J'ai cherché (pop Fr) 2015 Beach Boys - I Can Hear Music ( retro ) 1969 Beach Boys - Surfin' Safari ( retro) 1962 Cher - Hell On Wheels ( Dance) 1979 Chic - I Want Your Love ( disco) 1978 David Bowie - The Man Who Sold the World [BBC Radio Theatre, 2000] Dazz Band - Let It Whip ( disco) 1982 Deee-Lite - Groove Is in the Heart ( dance) 1990 Eagles - One of These Nights [Capital Centre, Largo, 1977] Elvis Presley - Heartbreak Hotel ( rock nroll) ETV Falco - Vienna Calling ( pop ) 2007 Fontella Bass - Rescue Me ( retro) 1966 Foreigne - Waiting For A Girl Like You (slow) 1981 Frank Stallone - Far From Over ( POP) Film Rocky George Benson - Turn Your Love Around (DISCO) 1981 George Duke, Stanley Clarke - Sweet Baby George Thorogood & The Destroyers - Bad To The Bone ( rock VB ) Glenn Frey - The Heat Is On (Beverly Hills Cop Soundtrack, 1985) Glenn Frey - You Belong To The City (POP) Hall & Oates - I Can't Go For That (No Can Do)BV Herb Alpert - Rotation ( POP) Kenny Loggins Playing With The Boys (Pop) Laura Branigan - Gloria ( DANCE DISCO) Laurence Jalbert - Rage (POP) - 1990 Leo Sayer More Than I Can Say ( pop) Lukas Graham - 7 Years ( country) 2016 Mr.Roboto - Styx ( pop) Nanette Workman ''Call girl'' (Clip), 1982 Nanette Workman Ce Soir On Danse à Naziland Patrick Hernandez - Born to Be Alive (disco ) 1979 Patsy Gallant - Sugar Daddy ( disco) Paula Abdul - Straight Up PIERRE LALONDE - HONEY HONEY( pop Detente) Prince & The N.P.G. -

Exclusive the Beastie Boy Behind the Bad Brains Comeback >P.5

AVRIL Rnirw Our EXPERIENCE THE BU EXCLUSIVE THE BEASTIE BOY BEHIND THE BAD BRAINS COMEBACK >P.5 4 li BRITNEYe BRANDING JAKES A 13EATING FINLAND: COLD COUNTRY, 91AR 10, 2007 HOT MARKET www.billboar > P.27 www.billboaru., ' r YOU US $6.99 CAN $8.99 UK £5.50 _at WOULD ****SCH 3-DIGIT 907 IA $6 991JS $8 99CAN 1113XACTCC ........... ..... C31.24080431 MAR08 REG A04 00/005 1 0> RD MONTY GREENLY 0074 RE 374D ELM AVE 1 A LONG BEACH CA 90807-3402 001261 > 11 P.15 o 71896 47205 9 J.T www.americanradiohistory.com soothing décor flawless design sublime amenities what can we do for you? AL_>(THE overnight or over time 203 impeccable guest rooms and deluxe suites interior design by David Rockwell flat- screen TVs in all bedrooms, bathrooms & living rooms 24 -hour room service from Riingo`' and award -winning chef, Marcus Samuelsson The Alex Hotel 205 East 45th Street at Third Avenue New York, NY 10017 212.867.5100 www.thealexhotel.com ©2007 The Alex Hotel The2eadimfiHotelsoftheWorld g www.americanradiohistory.com Billboard CON11 = \'l'S PAGE ARTIST/ TITLE NORAH JONES / THE BILBOARD 200 48 NOT TOO LATE NICKEL CREEK / TOP 3LUEGRASS 58 REASONS WHY (THE VERY BEST) KENNY WAYNE SHEPHERD I TOP BLUES 55 10 DAYS OUT BLUES FROM THE BfCKEJADi TOBYMAC / TOP CHRISTIAN 63 (PORTABLE SOUNDS) DIXIE CHICKS / TCP COUNTRY 58 TAKING THE LONG WAY GNARLS BARKLEY / TOP ELECTRONIC 61 ST ELSEWHERE J VARIOUS ARTISTS / -OP GOSPEL 63 WOW GOSPEL 2007 SILVERSUN PICKUPS / TOP HEATSEEKERS 65 CARNAVAS J THE SHINS / TOP INDEPENDENT 64 WINCING THE NIGHT AWAY VALENTIN ELIZALDE / TOP LATIN ' 60 VENCEDOR GERALD LEVERT / TOP R &B-HIP -HOP 55 IN MY SONGS UPFRONT WCINDA WILLIAMS / TASTE MAKERS 64 WEST 5 INSANE IN THE 16 Global CELTIC WOMAN / BRAINS Hardcore 18 The Indies TOP WORLD 64 A NEW JOURNEY legends get a lift 19 Legal Matters OSINGI_ES PAGE ARTIST / TITLE from a Beastie 20 On The Road JOHN MAYER / on new album.