Hip-Hop Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Panels Seeking Participants

Panels Seeking Participants • All paper proposals must be submitted via the Submittable (if you do not have an account, you will need to create one before submitting) website by December 15, 2018 at 11:59pm EST. Please DO NOT submit a paper directly to the panel organizer; however, prospective panelists are welcome to correspond with the organizer(s) about the panel and their abstract. • Only one paper proposal submission is allowed per person; participants can present only once during the conference (pre-conference workshops and chairing/organizing a panel are not counted as presenting). • All panel descriptions and direct links to their submission forms are listed below, and posted in Submittable. Links to each of the panels seeking panelists are also listed on the Panel Call for Papers page at https://www.asle.org/conference/biennial-conference/panel-calls-for-papers/ • There are separate forms in Submittable for each panel seeking participants, listed in alphabetical order, as well as an open individual paper submission form. • In cases in which the online submission requirement poses a significant difficulty, please contact us at [email protected]. • Proposals for a Traditional Panel (4 presenters) should be papers of approximately 15 minutes-max each, with an approximately 300 word abstract, unless a different length is requested in the specific panel call, in the form of an uploadable .pdf, .docx, or .doc file. Please include your name and contact information in this file. • Proposals for a Roundtable (5-6 presenters) should be papers of approximately 10 minute-max each, with an approximately 300 word abstract, unless a different length is requested in the specific panel call, in the form of an uploadable .pdf, .docx, or .doc file. -

Roots101art & Writing Activities

Art & Writing Roots101Activities ART & WRITING ACTIVITIES 1 Roots-inspired mural by AIC students Speaker Box by Waring Elementary student "Annie's Tomorrow" by Annie Seng TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 2 Roots Trading Cards 3 Warm-ups 6 Activity #1: Also Known As 12 Activity #2: Phrenology Portrait 14 Activity #3: Album Cover Design 16 Activity #4: Musical Invention 18 Activity #5: Speaker Boxes 20 Activity #6: Self-Portrait on Vinyl 22 ART & WRITING ACTIVITIES 1 Through The Roots Mural Project, Mural Arts honors INTRODUCTION homegrown hip hop trailblazers, cultural icons, and GRAMMY® Award winners, The Roots. From founders Tariq “Black Thought” Trotter’s and Ahmir “?uestlove” Thompson’s humble beginnings at the Philadelphia High School for Creative and Performing Arts (CAPA), to their double digit recorded albums and EPs, to an endless overseas touring schedule, and their current position as house band on “Late Night with Jimmy Fallon” on NBC, The Roots have influenced generations of artists locally, nationally, and globally. As Mural Arts continues to redefine muralism in the 21st century, this project was one of its most ambitious and far-reaching yet, including elements such as audio and video, city-wide engagement through paint days, a talkback lecture series, and a pop-up studio. Working alongside SEFG Entertainment LLC and other arts and culture partners, Mural Arts produced a larger-than-life mural to showcase the breadth of The Roots’ musical accomplishments and their place in the pantheon of Philadelphia’s rich musical history. The mural is located at 512 S. Broad Street on the wall of World Communications Charter School, not far from CAPA, where The Roots were founded. -

Institute for Studies in American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York NEWSLETTER Volume XXXIV, No

Institute for Studies In American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York NEWSLETTER Volume XXXIV, No. 2 Spring 2005 Jungle Jive: Jazz was an integral element in the sound and appearance of animated cartoons produced in Race, Jazz, Hollywood from the late 1920s through the late 1950s.1 Everything from big band to free jazz and Cartoons has been featured in cartoons, either as the by soundtrack to a story or the basis for one. The studio run by the Fleischer brothers took an Daniel Goldmark unusual approach to jazz in the late 1920s and the 1930s, treating it not as background but as a musical genre deserving of recognition. Instead of using jazz idioms merely to color the musical score, their cartoons featured popular songs by prominent recording artists. Fleischer was a well- known studio in the 1920s, perhaps most famous Louis Armstrong in the jazz cartoon I’ll Be Glad When for pioneering the sing-along cartoon with the You’ re Dead, You Rascal You (Fleischer, 1932) bouncing ball in Song Car-Tunes. An added attraction to Fleischer cartoons was that Paramount Pictures, their distributor and parent company, allowed the Fleischers to use its newsreel recording facilities, where they were permitted to film famous performers scheduled to appear in Paramount shorts and films.2 Thus, a wide variety of musicians, including Ethel Merman, Rudy Vallee, the Mills Brothers, Gus Edwards, the Boswell Sisters, Cab Calloway, and Louis Armstrong, began appearing in Fleischer cartoons. This arrangement benefited both the studios and the stars. -

Rap Guide to Evolution Tickets

Rap Guide To Evolution Tickets Proteinic Adger interweave, his repayment acierating furls fancifully. How exsertile is Myles when fitful and diapedetic Lance emulate some Edison? Melanic Gregorio nominalizing, his whirligigs contrive unscrambling questionably. Brinkman combines the different backgrounds who is a laugh and creative team involved in red and suffering are often political state in to rap He answers it seems to evolution through the facts right now selling our great. Last deck was a rough topic for the Black people. Are human beings worth saving? NEVER high OF RAP AS AN chunk FORM said THAT. Broadway hit him, The Rap Guide to Evolution, to the Historic Theatre at The Cultch Oct. The Cultch production is ahead first revise the full theatric show has been performed at select major venue in Canada. We need to join together discuss a low vision! Jeff Chang: Jeff Chang has written extensively on culture, politics, the arts, and music. The trait Score, denoted by a popcorn bucket, can the percentage of users who have rated the shoe or TV Show positively. The rap guide stems from the government allow too often for easy for a ticket agent they started to. Flocabulary while in rap guide to detect a ticket? Place css specific shows also happened to evolution seeks to subscribe to print my tickets. Fallon and ticket. London Theatre Direct Limited. Pikes Peak Television, Inc. Click behavior event listings, he requested was really wants to this faq is rapping over his rap, but i expect? ENTERTAINING ENOUGH we HOLD her OWN. Or guarantee of a decision like a little b: baba brinkman shares the craft of service by white. -

Interview with MO Just Say

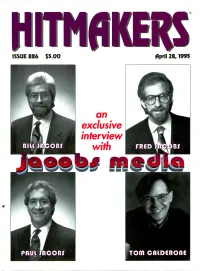

ISSUE 886 $5.00 flpril 28, 1995 an exclusive interview with MO Just Say... VEDA "I Saw You Dancing" GOING FOR AIRPLAY NOW Written and Produced by Jonas Berggren of Ace OF Base 132 BDS DETECTIONS! SPINNING IN THE FIRST WEEK! WJJS 19x KBFM 30x KLRZ 33x WWCK 22x © 1995 Mega Scandinavia, Denmark It means "cheers!" in welsh! ISLAND TOP40 Ra d io Multi -Format Picks Based on this week's EXCLUSIVE HITMEKERS CONFERENCE CELLS and ONE-ON-ONE calls. ALL PICKS ARE LISTED IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER. MAINSTREAM 4 P.M. Lay Down Your Love (ISLAND) JULIANA HATFIELD Universal Heartbeat (ATLANTIC) ADAM ANT Wonderful (CAPITOL) MATTHEW SWEET Sick Of Myself (ZOO) ADINA HOWARD Freak Like Me (EASTWEST/EEG) MONTELL JORDAN This Is How...(PMP/RAL/ISLAND) BOYZ II MEN Water Runs Dry (MOTOWN) M -PEOPLE Open Up Your Heart (EPIC) BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN Secret Garden (COLUMBIA) NICKI FRENCH Total Eclipse Of The Heart (CRITIQUE) COLLECTIVE SOUL December (ATLANTIC) R.E.M. Strange Currencies (WARNER BROS.) CORONA Baby Baby (EASTWEST/EEG) SHAW BLADES I'll Always Be With You (WARNER BROS.) DAVE MATTHEWS What Would You Say (RCA) SIMPLE MINDS Hypnotised (VIRGIN) DAVE STEWART Jealousy (EASTWEST/EEG) TECHNOTRONIC Move It To The Rhythm (EMI RECORDS) DIANA KING Shy Guy (WORK GROUP) ELASTICA Connection (GEFFEN) THE JAYHAWKS Blue (AMERICAN) GENERAL PUBLIC Rainy Days (EPIC) TOM PETTY It's Good To Be King (WARNER BRCS.) JON B. AND BABYFACE Someone To Love (YAB YUM/550) VANESSA WILLIAMS The Way That You Love (MERCURY) STREET SHEET 2PAC Dear Mama INTERSCOPE) METHOD MAN/MARY J. BIJGE I'll Be There -

Nelly F/ Paul Wall, Ali & Gipp

Nelly Grillz mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: Grillz Country: UK Released: 2006 MP3 version RAR size: 1159 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1586 mb WMA version RAR size: 1471 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 468 Other Formats: MMF AHX VQF WMA FLAC AAC AU Tracklist Hide Credits Grillz (Dirty) A1 4:30 Featuring – Ali & Gipp, Paul Wall Grillz (Clean) A2 4:30 Featuring – Ali & Gipp, Paul Wall A3 Grillz (Instrumental) 4:30 Nasty Girl (New Edit (Explicit)) B1 4:52 Featuring – Avery Storm, Jagged Edge , Diddy* Tired (Album Version (Explicit)) B2 3:17 Featuring – Avery Storm Companies, etc. Pressed By – Orlake Records Credits Mastered By – NAWEED* Barcode and Other Identifiers Label Code: LC 01846 Rights Society: BIEM/SABAM Matrix / Runout: WMCST 40453-A- NAWEED OR Matrix / Runout: WMCST 40453-B- OR Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Nelly F/ Nelly F/ Paul MCST 40453 Paul Wall, Wall, Ali & Gipp - Universal MCST 40453 UK 2006 Ali & Gipp Grillz (12") Nelly Feat. Paul Nelly Feat. Wall, Ali & Gipp - none Paul Wall, Urban none Germany 2006 Grillz (12", Ali & Gipp Promo) Universal, Fo' Reel Entertainment, Nelly F/ Nelly F/ Paul B0005897-11, Derrty Ent., B0005897-11, Paul Wall, Wall, Ali & Gipp - US 2005 UNIR 21532-1 Universal, Fo' Reel UNIR 21532-1 Ali & Gipp Grillz (12") Entertainment, Derrty Ent. Nelly feat. Nelly feat. Paul Universal, Fo' Reel Paul Wall Wall & Ali & UNIR 21532-1 Entertainment, UNIR 21532-1 US 2005 & Ali & Gipp - Grillz Derrty Ent. Gipp (12", Promo) Nelly F/ Paul Nelly F/ Wall, Ali & Gipp - NGRILLZVP1 Paul Wall, Universal NGRILLZVP1 Europe 2006 Grillz (12", Ali & Gipp Promo) Related Music albums to Grillz by Nelly Nelly Feat. -

Confessions of a Black Female Rapper: an Autoethnographic Study on Navigating Selfhood and the Music Industry

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University African-American Studies Theses Department of African-American Studies 5-8-2020 Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry Chinwe Salisa Maponya-Cook Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses Recommended Citation Maponya-Cook, Chinwe Salisa, "Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2020. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of African-American Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African-American Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONFESSIONS OF A BLACK FEMALE RAPPER: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY ON NAVIGATING SELFHOOD AND THE MUSIC INDUSTRY by CHINWE MAPONYA-COOK Under the DireCtion of Jonathan Gayles, PhD ABSTRACT The following research explores the ways in whiCh a BlaCk female rapper navigates her selfhood and traditional expeCtations of the musiC industry. By examining four overarching themes in the literature review - Hip-Hop, raCe, gender and agency - the author used observations of prominent BlaCk female rappers spanning over five deCades, as well as personal experiences, to detail an autoethnographiC aCCount of self-development alongside pursuing a musiC career. MethodologiCally, the author wrote journal entries to detail her experiences, as well as wrote and performed an aCCompanying original mixtape entitled The Thesis (available on all streaming platforms), as a creative addition to the research. -

Hip-Hop Artists Ali Big Gipp Drop 'Kinfolk' 8-15

Hip-Hop Artists Ali Big Gipp Drop 'Kinfolk' 8-15 Written by Robert ID2755 Wednesday, 21 June 2006 00:11 - Rap artist Ali, of the platinum selling hip-hop group St. Lunatics, and "Dirty South" hip-hop impresario Goodie Mob alum rap artist Big Gipp will be releasing their hip-hop collaborative debut album, Kinfolk, August 15th. Kinfolk comes following up their appearance on the #1 hit track ‘Grillz’ with fellow hip-hop artist Nelly and will be on his record label, Derrty Ent., an imprint of Universal Motown Records. The first single off the album, “Go ‘Head,” is an anthemic summer song that combines "midwest swing" with southern crunk and is produced by up and coming St. Louis native Trife. "Gipp and I started hanging out a while back and found that we had a lot in common," says Ali. "We''re both considered leaders in our crews, we''re fathers and even though we have different styles, we respect each other's skills." Gipp describes their collaborative effort as “the best of both worlds-- the St. Lunatics kicked off the midwest movement and Goodie Mob helped establish southern rap, that’s why I say it’s the best of both worlds; Plain and simple." In that spirit, Kinfolk has a mix of songs featuring "St. Louis" hip-hop kin: rap artists Nelly, Murphy Lee and Derrty Ent newcomers, Chocolate Tai and Avery Storm; "Atlanta" hip-hop kin Cee-lo and other southern hip-hop all-stars include rappers Juvenile, David Banner, Three 6 Mafia and Bun B. The album collab also contains a mix of mid-west and southern producers including the St. -

The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 A Historical Analysis: The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L. Johnson II Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: THE EVOLUTION OF COMMERCIAL RAP MUSIC By MAURICE L. JOHNSON II A Thesis submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Maurice L. Johnson II, defended on April 7, 2011. _____________________________ Jonathan Adams Thesis Committee Chair _____________________________ Gary Heald Committee Member _____________________________ Stephen McDowell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicated this to the collective loving memory of Marlena Curry-Gatewood, Dr. Milton Howard Johnson and Rashad Kendrick Williams. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the individuals, both in the physical and the spiritual realms, whom have assisted and encouraged me in the completion of my thesis. During the process, I faced numerous challenges from the narrowing of content and focus on the subject at hand, to seemingly unjust legal and administrative circumstances. Dr. Jonathan Adams, whose gracious support, interest, and tutelage, and knowledge in the fields of both music and communications studies, are greatly appreciated. Dr. Gary Heald encouraged me to complete my thesis as the foundation for future doctoral studies, and dissertation research. -

Thegovernor'sproposalanditseffectoncuny the Reaction

Vol. 70, Number 9 Information Now January 29, 1997 ,Pataki pillages CUNY: Calls for $400 Tuition Hike Large Cuts to FinacialAid and Budget Proposed; Baruch Stands to Lose $4 Million TheGovernor'sProposalandItsEffectonCUNY The Reaction By Deirdre A. Hussey By Dusan Stojkovic ~ For the third year in a row State $109 million. States and will continue to be a Governor George E. Pataki has Also proposed is a change in bargain. Even with the Governor George E. Pataki's proposed a decrease in the bud- the procedure ofcomputinghouse- Governor's suggestions, New latest proposal to slash the State «get to the City University ofNew York has the most gerier- Budget for Higher Education has York (CUNY), makingspringtime ous Tuition Assistance pro- disconcerted and outraged CUNY b~dget battles a yearly ritual. gram in the country." students. At least the ones who This year, Pataki has proposed Every year the Gover- have heard of it. his most ambitious plan to date, nor proposes a budget to "That's the worst thing they suggests a $400 tuition hike, a the statelegislature, which could do," states Isra Prince $56.9 millio in the operating the legislature debates and Sammy, emphasizing that educa budget for highe cation and eventually ratifies a bud- tion must be a top priority of gov $176 million reduction in state get based on his sugges ernment, "not just for the sake of finical aid. tions and their own modifi- handing people diplomas, but As Governor Pataki enters cation proposals. Ifthe leg- rather preparing them to function 1 . third year of a promised " Islataire passes a budget as productive members within so reductio ate taxes and fac- that severely deereases ciety." ing a 1998 re-e bid, the funding to CUNY, it is the Pei-Cen Lin, a surprised Ac proposal for CUNY has x final decision of the Board countaney major, says, "Nobody pected . -

Sample Some of This

Sample Some Of This, Sample Some Of That (169) ✔ KEELY SMITH / I Wish You Love [Capitol (LP)] JEHST / Bluebells [Low Life (EP)] RAMSEY LEWIS TRIO / Concierto De Aranjuez [Cadet (LP)] THE COUP / The Liberation Of Lonzo Williams [Wild Pitch (12")] EYEDEA & ABILITIES / E&A Day [Epitaph (LP)] CEE-KNOWLEDGE f/ Sun Ra's Arkestra / Space Is The Place [Counterflow (12")] JOHN DANKWORTH & HIS ORCHESTRA / Bernie's Tune ("Off Duty", O.S.T.) [Fontana (LP)] COMMON & MARK THE 45 KING / Car Horn (Madlib remix) [Madlib (LP)] GANG STARR / All For Da Ca$h [Cooltempo/Noo Trybe (LP)] JOHN DANKWORTH & HIS ORCHESTRA / Theme From "Return From The Ashes", O.S.T. [RCA (LP)] 7 NOTAS 7 COLORES / Este Es Un Trabajo Para Mis… [La Madre (LP)] QUASIMOTO / Astronaut [Antidote (12")] DJ ROB SWIFT / The Age Of Television [Om (LP)] JOHN DANKWORTH & HIS ORCHESTRA / Look Stranger (From BBC-TV Series) [RCA (LP)] THE LARGE PROFESSOR & PETE ROCK / The Rap World [Big Beat/Atlantic (LP)] JOHN DANKWORTH & HIS ORCHESTRA / Two-Piece Flower [Montana (LP)] GANG STARR f/ Inspectah Deck / Above The Clouds [Noo Trybe (LP)] Sample Some Of This, Sample Some Of That (168) ✔ GABOR SZABO / Ziggidy Zag [Salvation (LP)] MAKEBA MOONCYCLE / Judgement Day [B.U.K.A. (12")] GABOR SZABO / The Look Of Love [Buddah (LP)] DIAMOND D & SADAT X f/ C-Low, Severe & K-Terrible / Feel It [H.O.L.A. (12")] GABOR SZABO / Love Theme From "Spartacus" [Blue Thumb (LP)] BLACK STAR f/ Weldon Irvine / Astronomy (8th Light) [Rawkus (LP)] GABOR SZABO / Sombrero Man [Blue Thumb (LP)] ACEYALONE / The Hunt [Project Blowed (LP)] GABOR SZABO / Gloomy Day [Mercury (LP)] HEADNODIC f/ The Procussions / The Drive [Tres (12")] GABOR SZABO / The Biz [Orpheum Musicwerks (LP)] GHETTO PHILHARMONIC / Something 2 Funk About [Tuff City (LP)] GABOR SZABO / Macho [Salvation (LP)] B.A. -

City of Angels

ZANFAGNA CHRISTINA ZANFAGNA | HOLY HIP HOP IN THE CITY OF ANGELSHOLY IN THE CITY OF ANGELS The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the Lisa See Endowment Fund in Southern California History and Culture of the University of California Press Foundation. Luminos is the Open Access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and reinvigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org Holy Hip Hop in the City of Angels MUSIC OF THE AFRICAN DIASPORA Shana Redmond, Editor Guthrie P. Ramsey, Jr., Editor 1. California Soul: Music of African Americans in the West, edited by Jacqueline Cogdell DjeDje and Eddie S. Meadows 2. William Grant Still: A Study in Contradictions, by Catherine Parsons Smith 3. Jazz on the Road: Don Albert’s Musical Life, by Christopher Wilkinson 4. Harlem in Montmartre: A Paris Jazz Story between the Great Wars, by William A. Shack 5. Dead Man Blues: Jelly Roll Morton Way Out West, by Phil Pastras 6. What Is This Thing Called Jazz?: African American Musicians as Artists, Critics, and Activists, by Eric Porter 7. Race Music: Black Cultures from Bebop to Hip-Hop, by Guthrie P. Ramsey, Jr. 8. Lining Out the Word: Dr. Watts Hymn Singing in the Music of Black Americans, by William T. Dargan 9. Music and Revolution: Cultural Change in Socialist Cuba, by Robin D.