Volume 3 • 2018 Published by Mcgill University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Ebook ^ Danny Clinch: Still Moving: Still Moving (Hardback

NUCV5NZOQOEH \\ Doc « Danny Clinch: Still Moving: Still Moving (Hardback) Danny Clinch: Still Moving: Still Moving (Hardback) Filesize: 7.24 MB Reviews Extensive manual for book fans. It really is simplified but surprises inside the fifty percent of your pdf. I realized this pdf from my dad and i advised this pdf to discover. (Geoffrey Wiza) DISCLAIMER | DMCA N9T5RHWDOZTM > PDF > Danny Clinch: Still Moving: Still Moving (Hardback) DANNY CLINCH: STILL MOVING: STILL MOVING (HARDBACK) To save Danny Clinch: Still Moving: Still Moving (Hardback) eBook, you should refer to the button under and save the file or gain access to other information that are relevant to DANNY CLINCH: STILL MOVING: STILL MOVING (HARDBACK) ebook. Abrams, United States, 2014. Hardback. Condition: New. Language: English . Brand New Book. Danny Clinch has established himself as one of the premiere photographers of the popular music scene. He has photographed a wide range of artists from Johnny Cash and Tupac Shakur to Bjork and Bruce Springsteen. His photos have appeared on hundreds of album covers as well as in publications such as Vanity Fair, Spin, Rolling Stone, GQ, Esquire and the New York Times Magazine. Famous for his ad campaigns for John Varvatos, which feature a wide variety of rock stars, Clinch has also received two Grammy Award nominations for Bruce Springsteen s Devils and Dust and for John Mayer s Where the Light Is. He has also directed music videos and concert films for Willie Nelson, Tom Waits, Pearl Jam, John Legend, Melissa Etheridge, Foo Fighters, Dave Matthews and the Bonnaroo music festival. This lavish monograph chronicles Danny Clinch s illustrious career with over 200 photographs of the most important musicians of all time, along with his personal memorabilia, anecdotes and four celebrity essays. -

Download Internet Service Channel Lineup

INTERNET CHANNEL GUIDE DJ AND INTERRUPTION-FREE CHANNELS Exclusive to SiriusXM Music for Business Customers 02 Top 40 Hits Top 40 Hits 28 Adult Alternative Adult Alternative 66 Smooth Jazz Smooth & Contemporary Jazz 06 ’60s Pop Hits ’60s Pop Hits 30 Eclectic Rock Eclectic Rock 67 Classic Jazz Classic Jazz 07 ’70s Pop Hits Classic ’70s Hits/Oldies 32 Mellow Rock Mellow Rock 68 New Age New Age 08 ’80s Pop Hits Pop Hits of the ’80s 34 ’90s Alternative Grunge and ’90s Alternative Rock 70 Love Songs Favorite Adult Love Songs 09 ’90s Pop Hits ’90s Pop Hits 36 Alt Rock Alt Rock 703 Oldies Party Party Songs from the ’50s & ’60s 10 Pop 2000 Hits Pop 2000 Hits 48 R&B Hits R&B Hits from the ’80s, ’90s & Today 704 ’70s/’80s Pop ’70s & ’80s Super Party Hits 14 Acoustic Rock Acoustic Rock 49 Classic Soul & Motown Classic Soul & Motown 705 ’80s/’90s Pop ’80s & ’90s Party Hits 15 Pop Mix Modern Pop Mix Modern 51 Modern Dance Hits Current Dance Seasonal/Holiday 16 Pop Mix Bright Pop Mix Bright 53 Smooth Electronic Smooth Electronic 709 Seasonal/Holiday Music Channel 25 Rock Hits ’70s & ’80s ’70s & ’80s Classic Rock 56 New Country Today’s New Country 763 Latin Pop Hits Contemporary Latin Pop and Ballads 26 Classic Rock Hits ’60s & ’70s Classic Rock 58 Country Hits ’80s & ’90s ’80s & ’90s Country Hits 789 A Taste of Italy Italian Blend POP HIP-HOP 750 Cinemagic Movie Soundtracks & More 751 Krishna Das Yoga Radio Chant/Sacred/Spiritual Music 03 Venus Pop Music You Can Move to 43 Backspin Classic Hip-Hop XL 782 Holiday Traditions Traditional Holiday Music -

Pearl Jam to Release Live Italian Concert Film Immagine in Cornice (Picture in a Frame) on September 25

For Immediate Release: July 31, 2007 PEARL JAM TO RELEASE LIVE ITALIAN CONCERT FILM IMMAGINE IN CORNICE (PICTURE IN A FRAME) ON SEPTEMBER 25 FILM IS DIRECTED BY DANNY CLINCH AND INCLUDES OVER AN HOUR AND A HALF OF LIVE PERFORMANCES AND RARE, BEHIND-THE-SCENES FOOTAGE FROM THE BAND'S 2006 ITALIAN CONCERT DATES SEATTLE, WA- Pearl Jam announces the release of Immagine in Cornice "Picture in a Frame" (Monkeywrench Records), a live concert film chronicling the band's performances with behind-the-scenes footage from the five Italian concerts that took place as part of the band’s 2006 European tour. Featured cities and venues include: Pala Malaguti in Bologna, the Arena di Verona, the Forum in Milan, Palaisozaki in Torino and Duomo Square in Pistoia, Italy. A limited edition commemorative t-shirt will be available for a special price when purchased with Immagine in Cornice at www.pearljam.com during a special pre-sale beginning August 22. Immagine in Cornice will be released at retail stores on Tuesday, September 25. Immagine in Cornice was directed by renowned photographer, filmmaker and long-time friend of the band Danny Clinch (Bruce Springsteen Devils and Dust, Live from Bonnaroo 2004) and was shot in High Definition, Super-8 and a number of formats in between. ''Picture in a Frame'' is a film I've really wanted to make," says director Danny Clinch. "The band invited me to Italy and gave me the access I needed to show a side seldom seen by their fans. It has become a collaboration, as well - the band even offered me some music that has never been heard and Mike (McCready) went into the studio to create some more music for the soundscapes. -

Bruce Springsteen. Further up the Road

BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN. FURTHER UP THE ROAD Photographs by FRANK STEFANKO Introduction by Bruce Springsteen Text by Frank Stefanko Forewords by Danny Clinch, Eric Meola The Signed Limited Edition Book Published November 2017 by Wall of Sound Editions "Frank’s photographs were stark. His talent was he managed to strip away your celebrity, your artifice, and get to the raw you. His photos had a purity and a street poetry to them. They were lovely and true, but they weren’t slick. Frank looked for your true grit and he naturally intuited the conflicts I was coming to terms with. His pictures captured the people I was writing about in my songs and showed me the part of me that was still one of them. We had other cover options but they didn’t have the hungriness of Frank’s pictures.” – Bruce Springsteen (Reprinted by permission from "Born To Run", Simon & Schuster, 2016) Wall of Sound Editions will publish a phenomenal new limited edition book of photographs of Bruce Springsteen made by Frank Stefanko. BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN. FURTHER UP THE ROAD will be published in November 2017 and is an astounding anthology of over 40 years of largely unseen images of Springsteen, all shot by Stefanko throughout Springsteen’s epic career. Frank Stefanko has spent over four decades working closely with Bruce Springsteen. He shot the iconic covers for Darkness on the Edge of Town and The River albums as well as the cover shot for Springsteen's best-selling Born To Run autobiography and accompanying album Chapter And Verse. The new hardback collectors edition features a personal introduction text by Bruce Springsteen himself and is packed full of unseen photos and features, with image captions and text by Stefanko and forewords by fellow Springsteen photographers Eric Meola, who shot the Born To Run and The Promise album covers, and Danny Clinch, who shot the Devils & Dust, The Rising, The Seeger Sessions, and Working on a Dream album covers. -

SUMMER 2010 MAGAZINE University

VOL. XXX, NO. 3 NO. XXX, VOL. Monmouth SUMMER 2010 MAGAZINE university CommenCement shines Finding sPRingsteen bioniC men c1-48moma_sum10.indd 1 9/1/10 11:13 AM Calendar of MonmouthMAGAZINE university EVENTS SEPTEMBER 21 OCTOBER 8 Volume XXX, No. 3 AUGUST Visiting Writer Series: MIHAELA Performing Arts: FRANK Summer 2010 AUGUST 9 MOSCALIUC WARREN – SEPTEMBER 16 4:30 PM “PostSecret with The Most Paul G. Gaffney II Wilson Hall Auditorium Trusted Stranger in America” Gallery Exhibition: QUILTING President Free and open to the public Pollak Theatre - LOOKING FORWARD $20 Jeffery n. MIlls M - F 9:00 AM – 5:00 PM SEPTEMBER 23 Vice President for University Advancement Pollak Art Gallery MACE Award—NBC Nightly OCTOBER 9 Publisher Free and open to the public News’ Brian Williams The Met: Live in HD Multipurpose Activity Center DAS RHEINGOLD - Wagner MIchael sayre MaIden, Jr. SEPTEMBER (MAC) Pollak Theatre Editor 6:15 PM VIP Reception/Program 1:00 PM SEPTEMBER 7 /$75 $23 adults/$20 seniors heather Mcculloch MIstretta – OCTOBER 22 7:30 PM “An Evening with Brian OCTOBER 14 Assistant Editor Gallery Exhibition: Williams & Friends”/$25 TED HENDRICKSON For more information call 732- Kislak Real Estate Institute Golf Invitational Contributing Writers “Time in the Irish Landscape” 571-3509 M - F 9:00 AM – 5:00 PM Hollywood Golf Club, Deal russell carstens '07 800 Gallery SEPTEMBER 23 10:00 AM – Registration ellIott denMan Gallery Exhibition Opening Performing Arts: LA BRUJA 12:15 – Shotgun Tee Off frank GoGol '10 September 16 4:00 PM 5:30 PM – Cocktails & Dinner susan MerrIll o’connor '88 4:30 – 5:30 PM Lecture at Wilson Woods Theatre Call 732-571-4412 for details. -

Internet Channel Guide

STREAMING Channel Guide DJ AND INTERRUPTION-FREE CHANNELS Exclusive to SiriusXM Music for Business Customers 02 Top 40 Hits Top 40 Hits 25 Rock Hits ’70s & ’80s ’70s & ’80s Classic Rock 58 Country Hits ’80s & ’90s ’80s & ’90s Country Hits 06 ’60s Pop Hits ’60s Pop Hits 26 Classic Rock Hits ’60s & ’70s Classic Rock 63 Contemporary Christian Christian Pop & Rock 07 ’70s Pop Hits Classic ’70s Hits/Oldies 28 Adult Alternative New/Classic Alt Rock 66 Smooth Jazz Smooth & Contemporary Jazz 08 ’80s Pop Hits Pop Hits of the ’80s 34 ’90s Alternative 90s Alternative/Grunge 67 Classic Jazz Classic Jazz 09 ’90s Pop Hits ’90s Pop Hits 36 Alt Rock New Alt Rock 68 New Age New Age 10 Pop 2000 Hits Pop 2000 Hits 48 R&B Hits R&B Hits from the ’80s, ’90s & Today 70 Love Songs Favorite Adult Love Songs 14 Acoustic Rock Acoustic Singer-Songwriters Classic Soul & Motown Classic Soul & Motown 703 Oldies Party Party Songs from the ’50s & ’60s 15 Pop Mix Modern Adult Pop Hits 49 Modern Dance Hits Current Dance Seasonal/Holiday 16 Pop Mix Bright Blend of Bright Pop Hits 51 709 Seasonal/Holiday Music Channel 17 Mellow Rock Mellow Rock 53 Smooth Electronic Smooth Electronic 763 Latin Pop Hits Contemporary Latin Pop and Ballads 24 Radio Margaritaville Escape to Margaritaville 56 New Country Today’s New Country 789 A Taste of Italy Italian Blend Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Radio B.B. King’s Bluesville B.B. King’s Blues Channel POP 310 Rock Hall Inducted Artists 74 04 SoulCycle Radio Music to Energize Your Soul 311 Yacht Rock Radio ’70s/’80s Smooth-Sailing Soft Rock -

2011 Starwood Hotels & Resorts Worldwide, Inc. All

W SOUTH BEACH DANNY CLINCH ART COLLECTION ©2011 Starwood Hotels & Resorts Worldwide, inc. All rights reserved. Confidential & proprietary – may not be reproduced or distributed without written permission of Starwood Hotels & Resorts Worldwide, Inc. DANNY CLINCH ©2011 Starwood Hotels & Resorts Worldwide, inc. All rights reserved. Confidential & proprietary – may not be reproduced or distributed without written permission of Starwood Hotels & Resorts Worldwide, Inc. WHO IS DANNY CLINCH? DANNY CLINCH is an award winning photographer and filmmaker who has established himself as one of the premiere photographers of the popular music scene. Born in Toms River, New Jersey, Clinch attended Ocean County College and earned his degree at New England School of Photography in Boston, Massachusetts. Clinch began his career as an intern for Annie Leibovitz and assisted Steven Meisel, Timothy White and Mary Ellen Mark. He went on to photograph the likes of Johnny Cash, Bruce Springsteen, Tupac Shakur, Neil Young, Dave Matthews Band, Phish, Radiohead and Björk. His unobtrusive style is one of the features that Clinch's photographic subjects enjoy. Danny has shot many highly regarded advertising campaigns for clients such as John Varvatos, Absolut, Dewar’s, Ray-Ban, Jeep, NASCAR, to name a few. His work has also appeared in publications such as Vanity Fair, Rolling Stone, GQ, Esquire, The New Yorker, and The New York Times Magazine. His photographs have also graced the covers of hundreds of albums. Clinch has presented his work in numerous galleries around the world and published two books: Discovery Inn (1998) and When the Iron Bird Flies (2000). As a director, Clinch has received 2 Grammy Award nominations: in 2005 for Bruce Springsteen’s “Devils and Dust” and in 2009 for John Mayer’s “Where The Light Is.” He has also directed music videos for Willie Nelson, Tom Waits, Pearl Jam, John Legend, Mellissa Etheridge, Foo Fighters and Dave Matthews, among others. -

SIRIUS Satellite Radio's 'E Street Radio' Channel to Launch with Rare Bruce Springsteen Concert

SIRIUS Satellite Radio's 'E Street Radio' Channel to Launch with Rare Bruce Springsteen Concert NEW YORK, Sept 27, 2007 /PRNewswire-FirstCall via COMTEX News Network/ -- SIRIUS Satellite Radio (Nasdaq: SIRI) announced today that E Street Radio, the exclusive commercial- free channel dedicated to the music of Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band, will debut today with a rare concert recording featuring Springsteen and the band performing at the Capitol Theater in Passaic, New Jersey in 1978. The concert from the Darkness On The Edge Of Town tour is regarded as one of Bruce's greatest live performances and exemplifies all the elements of an E Street Band Show. (Logo: http://www.newscom.com/cgi-bin/prnh/19991118/NYTH125 ) (Photo: http://www.newscom.com/cgi-bin/prnh/20070920/NYTH115 ) The channel launches today at 6 pm ET, on SIRIUS channel 10, and will run on SIRIUS through late March 2008. The launch of E Street Radio on SIRIUS coincides with the start of the band's 2007 concert tour, as well as the October 2nd release of Magic, Bruce Springsteen's highly-anticipated first album recorded with the E Street Band since 2002's multi- platinum and Grammy(R) award-winning The Rising. Listeners will be able to hear daily features on the new album's music and track-by- track discussions with Bruce Springsteen and E Street Band members. The E Street Radio channel will also feature archival concert recordings of Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band dating from early 1973 and behind-the-scenes insights from band insiders. -

Bruce Springsteen & the E St Band 2008 Tour Program

I want a thousand guitars I want pounding drums Radio Nowhere I want a million different I was tryin’ to find my way home voices speaking in tongues But all I heard was a drone Bouncing off a satellite This is radio nowhere, Crushin’ the last lone American night is there anybody alive out there? This is radio nowhere, This is radio nowhere, is there anybody alive out there? is there anybody alive out there? This is radio nowhere, Is there anybody alive out there? is there anybody alive out there? I was driving through the misty rain I was spinnin’ ’round a dead dial Searchin’ for a mystery train Just another lost number in a file Boppin’ through the wild blue Dancin’ down a dark hole Tryin’ to make a connection with you Just searchin’ for a world with some soul This is radio nowhere, is there anybody alive out there? This is radio nowhere, This is radio nowhere, is there anybody alive out there? is there anybody alive out there? This is radio nowhere, Is there anybody alive out there? is there anybody alive out there? Is there anybody alive out there? I just want to feel some rhythm I just want to feel some rhythm I just want to hear some rhythm I just want to feel your rhythm I just want to hear some rhythm I just want to feel your rhythm I just want to hear some rhythm I just want to feel your rhythm I just want to hear some rhythm I just want to feel your rhythm I just want to feel your rhythm I just want to feel your rhythm You’ll Be Comin’ Down White roses and misty blue eyes Red mornings, then nothin’ but gray skies A cup of coffee, -

Hear Tom Morello Across Siriusxm, with New Streaming Channels, Weekly Show and Podcast

NEWS RELEASE Hear Tom Morello Across SiriusXM, with New Streaming Channels, Weekly Show and Podcast 2/24/2021 Renowned rock guitarist Morello, of Rage Against the Machine and Audioslave, launches suite of audio content exploring music, activism, and personal musical inuences New podcast will examine the music and world movements that dene Morello NEW YORK, Feb. 24, 2021 /PRNewswire/ -- SiriusXM announced today a new collaboration with groundbreaking rock guitarist and acoustic troubadour, Tom Morello, including all-original content that spans three new streaming music channels and a new additional weekly show beginning March 2, and an original podcast, beginning March 3. The content hand-crafted by Morello includes streaming music channels that are part of SiriusXM's Xtra Channels oering, which has expanded even more since its debut of 100 curated music channels in early 2019. Morello's music channels will amplify the intersection where music and activism collide, a wide-range of heavy metal music, and will explore his personal inuences and musical collection. See channel info below. "When SiriusXM approached me about doing a new slate of shows, I only had one condition: I say what I wanna say and I play what I wanna play," said Morello. "When the right combination of rhythm and rhyme washes over a huge throng or transmits through an ear bud it can provide a spark for action or a life raft for survival. Music MATTERS. And I'm very much looking forward to inicting on listeners the music that matters to me." "We are more than excited for Tom to bring his unique and respected voice in both music and activism across multiple platforms to our listeners," said Scott Greenstein, President and Chief Content Ocer, SiriusXM. -

Public Programs

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACTS: Ashley Berke Lauren Saul Director of Public Relations Public Relations Manager 215.409.6693 215.409.6895 [email protected] [email protected] NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER HOSTS SPECIAL PROGRAMS AND EVENTS CELEBRATING BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN AND THE FIRST AMENDMENT Philadelphia, PA – In connection with the must-see exhibition From Asbury Park to the Promised Land: The Life and Music of Bruce Springsteen , visitors of all ages can celebrate freedom of expression during interactive programs and special events at the National Constitution Center. Special Events Greetings from Asbury Park: Opening Celebration Wednesday, February 15, 2012, 5:30 p.m. – 9:30 p.m. Please note: Tickets to this event are now SOLD OUT In homage to the city where Springsteen got his start, this festive opening party features boardwalk-themed décor and festivities; nostalgic summertime treats including hot dogs, boardwalk fries, popcorn, and salt water taffy; live musical performances; and the exclusive chance to tour From Asbury Park to the Promised Land before it opens to the public. Guests also can enjoy a special presentation of framed, large-scale original works by New Jersey-based photographers Frank Stefanko and Danny Clinch from “Darkness to a Dream,” an exhibition at New York’s Morrison Hotel Gallery. Stefanko is famous for shooting the cover art for Darkness on the Edge of Town and The River , while the covers of The Seeger Sessions , The Rising, and Working on a Dream were taken by Clinch. Original, signed prints by both photographers will be available for purchase in the museum gift shop throughout the run of the exhibition. -

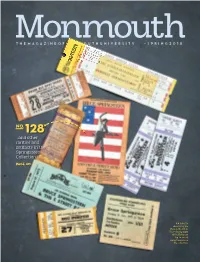

No. 128 ...And Other Rarities and Artifacts in the Springsteen Collection Page 40

THE MAGAZINE OF MONMOUTH UNIVERSITY » SPRING 2018 No. 128 ...and other rarities and artifacts in the Springsteen Collection page 40 * A ticket to show 128 of the Born in the U.S.A. Tour—closing night of the European leg—is one of many treasures in the collection. w ROCKROCKROCK RELICSRELICSRELICS THE BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN SPECIAL COLLECTION, WHICH IS HOUSED AT MONMOUTH UNIVERSITY, IS LIKE THE PROMISED LAND FOR FANS OF THE BOSS. The almost-made-it One of several alternate photos considered for the Born in the U.S.A. album cover. The now-iconic red hat that’s shoved into Bruce’s back pocket on the PHOTOS BY MATT FURMAN actual cover is also part of the Special Collection. When Monmouth University “Given the importance of Bruce announced plans for its Springsteen’s work in our own wcollaborative partnership to lives, we wanted to preserve and establish The Bruce Springsteen consolidate all this material before wArchives and Center for American it faded away. But I don’t think Music, global interest in the Bruce either of us imagined how much the wSpringsteen Special Collection collection would grow—thanks to skyrocketed. the dedication, labor, and generosity A portion of the collection, of fans worldwide—and that we’d composed of Springsteen’s written eventually find such a perfect home. works, photographs, periodicals, As a founder, I couldn’t be more and artifacts, had been on loan to pleased to have discovered a partner Monmouth since 2011. In 2017, it was in Monmouth University to preserve formally gifted to the university for and expand the collection for future inclusion in the Archives by The generations.” Friends of the Bruce Springsteen The collection originated in 2001 Special Collection Inc., a nonprofit when Backstreets organized a organization established to help fan-to-fan campaign to collect and preserve the history of the singer organize essential documents from and his music.