The Hamilton Inventories Project Celia Curnow Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Four Iron Steamships of William Alexander Lewis Stephen Douglas – Hamilton

The Four Iron Steamships of William Alexander Lewis Stephen Douglas – Hamilton. KT 12th Duke of Hamilton, 9th Duke of Brandon, 2nd Duke of Châtellerault Second Edition. 1863 Easton Park, Suffolk, England (Demolished 1925) Hamilton Palace, Scotland (Demolished 1927) Brian Boon & Michel Waller Introduction The families residing in the village of Easton, Suffolk experienced many changing influences over their lives during the 92 year tenure of four generations of the Hamilton family over the 4,883 acre Easton Park Estate. The Dukes of Hamilton were the Premier Dukedom of Scotland, owning many mansions and estates in Scotland together with other mining interests. These generated considerable income. Hamilton Palace alone, in Scotland, had more rooms than Buckingham Palace. Their fortunes varied from the extremely wealthy 10th Duke Alexander, H.M. Ambassador to the Court of the Czar of Russia, through to the financial difficulties of the 12th Duke who was renowned for his idleness, gambling and luxurious lifestyle. Add to this the agricultural depression commencing in 1870. On his death in 1895, he left debts of £1 million even though he had previously sold the fabulous art and silver collections of his grandparents. His daughter, Mary, then aged 10 inherited Easton and the Arran estates and remained in Easton, with the Dowager Duchess until 1913 when she married Lord Graham. The estates were subsequently sold and the family returned to Arran. This is an account of the lives of the two passenger paddle steamers and two large luxury yachts that the 12th Duke had built by Blackwood & Gordon of Port Glasgow and how their purchase and sales fitted in with his varying fortunes and lifestyle. -

Introduction to the Abercorn Papers Adobe

INTRODUCTION ABERCORN PAPERS November 2007 Abercorn Papers (D623) Table of Contents Summary ......................................................................................................................2 Family history................................................................................................................3 Title deeds and leases..................................................................................................5 Irish estate papers ........................................................................................................8 Irish estate and related correspondence.....................................................................11 Scottish papers (other than title deeds) ......................................................................14 English estate papers (other than title deeds).............................................................17 Miscellaneous, mainly seventeenth-century, family papers ........................................19 Correspondence and papers of the 6th Earl of Abercorn............................................20 Correspondence and papers of the Hon. Charles Hamilton........................................21 Papers and correspondence of Capt. the Hon. John Hamilton, R.N., his widow and their son, John James, the future 1st Marquess of Abercorn....................22 Political correspondence of the 1st Marquess of Abercorn.........................................23 Political and personal correspondence of the 1st Duke of Abercorn...........................26 -

Clan Douglas

CLAN DOUGLAS ARMS Quarterly, 1st, Azure, a man’s heart ensigned of an Imperial Crown Proper and on a chief Azure three stars of the Field (Douglas) CREST A salamander Vert encircled with flames of fire Proper MOTTO Jamais arriére (Never behind) SUPPORTERS (on a compartment comprising a hillock, bounded by stakes of wood wreathed round with osiers) Dexter, a naked savage wreathed about the head and middle with laurel and holding a club erect Proper; sinister, a stag Proper, armed and unguled Or The Douglases were one of Scotland’s most powerful families. It is therefore remarkable that their origins remain obscure. The name itself is territorial and it has been suggested that it originates form lands b Douglas Water received by a Flemish knight from the Abbey of Kelso. However, the first certain record of the name relates to a William de Dufglas who, between 1175 and 1199, witnessed charter by the Bishop of Glasgow to the monks of Kelso. Sir William de Douglas, believed to be the third head of the Borders family, had two sons who fought against the Norse at the Battle of Largs in 1263. William Douglas ‘The Hardy’ was governor of Berwick when the town was besieged by the English. Douglas was taken prisoner when the town fell and he was only released when he agreed to accept the claim of Edward I of England to be overlord of Scotland. He later joined Sir William Wallace in the struggle for Scottish independence but he was again captured and died in England in 1302. -

The Heraldry of the Hamiltons

era1 ^ ) of t fr National Library of Scotland *B000279526* THE Heraldry of the Ibamiltons NOTE 125 Copies of this Work have been printed, of which only 100 will be offered to the Public. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/heraldryofhamilsOOjohn PLATE I. THE theraldry of m Ibamiltons WITH NOTES ON ALL THE MALES OF THE FAMILY DESCRIPTIONS OF THE ARMS, PLATES AND PEDIGREES by G. HARVEY JOHNSTON F.S.A., SCOT. AUTHOR OF " SCOTTISH HERALDRY MADE EASY," ETC. *^3MS3&> W. & A. K. JOHNSTON, LIMITED EDINBURGH AND LONDON MCMIX WORKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR. circulation). 1. "THE RUDDIMANS" {for private 2. "Scottish Heraldry Made Easy." (out print). 3. "The Heraldry of the Johnstons" of {only a few copies remain). 4. "The Heraldry of the Stewarts" Douglases" (only a few copies remain). 5. "The Heraldry of the Preface. THE Hamiltons, so far as trustworthy evidence goes, cannot equal in descent either the Stewarts or Douglases, their history beginning about two hundred years later than that of the former, and one hundred years later than that of the latter ; still their antiquity is considerable. In the introduction to the first chapter I have dealt with the suggested earlier origin of the family. The Hamiltons were conspicuous in their loyalty to Queen Mary, and, judging by the number of marriages between members of the different branches, they were also loyal to their race. Throughout their history one hears little of the violent deeds which charac- terised the Stewarts and Douglases, and one may truthfully say the race has generally been a peaceful one. -

By Arthur Wentworth Hamilton Eaton

V| \>: !/ 3»: y ¦li rfe." 63^ 1 I1I> f"y -x: I" *: -, §tJe ([H&Mtoi4|amUtons V 1 ."» !¦ V ff-,. ¦ *¦ W? #>¦¦ %?>,^ L-tSC'irs \ N *?i»-', '-¦^SS"¦- .^ .v*?i»-',.v /«*V ft Arms ofthe Ducal House ofHamilton from which, through SirDavid Hamilton of Cadzow, a second son, John Hamilton of Huirhouse and Oliveetob, sprang: Gules, three cinquefoils ermine (or later, pierced ermine). Crest: Out of a ducal coronet, an oak tree fructed and penetrated transversely in the main stem by a frame s&vrproper, the frame or. Motto, "Through." Arms probably borne by the Boreland Hamiltons and their descendant John Ham iltonofMuirhouse and Olivestob, and about 1700, formally assumed by John Hamilton's descendants, the Hamiltons of Innerdovat: Gules, a crescent argent between three cinquefoils ermine within abordure embattled or. Arms of Colonel Thomas Hamilton of Olivestob, fourth son of John Hamiltonof Muirhouse and Olivestob, registered 1678: Gules, a martlet between three cinquefoils argent, within abordure" embattled or. Crest: Anantelope's head proper, gorged and attired gules. Motto, Invia virtutifervia" ) \ V When princely Hamilton's abode f Ennobled Cadyow's Gothic towers, The song went round, the goblet flow'd, Andrevel sped the laughing hours, Then, thrilling to the harp's gay sound, So sweetly rung each vaulted wall. And echoed light the dancer's bound, As mirthand music cheer'd the hall. But Cadyow's towers, inrains laid, And vaults, by ivymantled o'er, Thrillto the music ofthe shade, Or echo Evan's hoarier roar. " (From Sir Walter Scott's Cadyow Castle.") > ftbe ©Hveetob Immtttons powerful and widely spread family ofHamilton traces" to Walter THEFitz-Gilbert, who as Sir" WilliamFraser inhis recent Memorials of the Earls of Haddington says, is now admitted by allwriters tohave been its earliest authenticated ancestor, the current traditions of the family's noble English ancestry having been cast aside. -

Royal Flush Or Not? Understanding Royalty, Nobility and Gentry

Royal Flush or Not? Understanding Royalty, Nobility and Gentry Craig L. Foster, A.G.® [email protected] Definition of Royalty and Nobility The difference between royalty and nobility is that royalty “means that they were born into their position. Therefore only the king and queen and their direct relations can be considered royalty. … Nobility is a title conferred on a person if they meet certain requirements.” “The Aristocracy of England,” http://www.aristocracyuk.co.uk/ Royalty Definition of royalty is people of royal blood or status. Ranks of Royalty – King or Queen Prince Princess The royal family includes the immediate royal heirs as well as the extended family. Many also hold noble titles such as the Duke of Cornwall, which the heir apparent to the throne, and the Duke of York, as well as the Duke of Cambridge. www.royal.gov.uk Nobility Originally, nobility grew out of the feudal warrior classes. Nobles and knights were warriors who swore allegiance to the king in exchange for land. “Peers, Peeresses and other People,” www.avictorian.com/nobility.html “…hereditary permanent rank is what most Englishmen prize above all earthly honours. It is the permanency, especially, that they value.” Beckett, The Aristocracy in England, 1660-1914, p. 92 Noble Titles and Order of Precedence – Duke Marquess Earl Viscount Baron A peer of the realm is someone who holds one or more of the above titles. The peerage is a continuation of the original baronage system which existed in feudal times. “Historically the peerage formed a tightly knit group of powerful nobles, inter-related through blood and marriage in successive generations…” Debrett’s Essential Guide to the Peerage and Wikipedia In Scots law, there are certain titles that are recognized by the Crown as almost comparable to but not quite at the level of the peerage. -

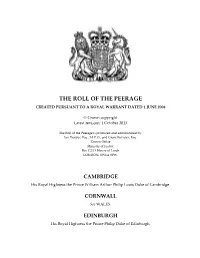

Roll of the Peerage Created Pursuant to a Royal Warrant Dated 1 June 2004

THE ROLL OF THE PEERAGE CREATED PURSUANT TO A ROYAL WARRANT DATED 1 JUNE 2004 © Crown copyright Latest revision: 1 October 2013 The Roll of the Peerage is produced and administered by: Ian Denyer, Esq., M.V.O., and Grant Bavister, Esq. Crown Office Ministry of Justice Rm C2/13 House of Lords LONDON, SW1A 0PW. CAMBRIDGE His Royal Highness the Prince William Arthur Philip Louis Duke of Cambridge. CORNWALL See WALES. EDINBURGH His Royal Highness the Prince Philip Duke of Edinburgh. GLOUCESTER His Royal Highness Prince Richard Alexander Walter George Duke of Gloucester. KENT His Royal Highness Prince Edward George Nicholas Paul Patrick Duke of Kent. ROTHESAY See WALES. WALES His Royal Highness the Prince Charles Philip Arthur George Prince of Wales (also styled Duke of Cornwall and Duke of Rothesay). WESSEX His Royal Highness the Prince Edward Antony Richard Louis Earl of Wessex. YORK His Royal Highness the Prince Andrew Albert Christian Edward Duke of York. * ABERCORN Hereditary Marquess in the Peerage of the United Kingdom: James Marquess of Abercorn (customarily styled by superior title Duke of Abercorn). Surname: Hamilton. ABERDARE Hereditary Baron in the Peerage of the United Kingdom (hereditary peer among the 92 sitting in the House of Lords under the House of Lords Act 1999): Alaster John Lyndhurst Lord Aberdare. Surname: Bruce. ABERDEEN AND TEMAIR Hereditary Marquess in the Peerage of the United Kingdom: Alexander George Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair. Surname: Gordon. ABERGAVENNY Hereditary Marquess in the Peerage of the United Kingdom: Christopher George Charles Marquess of Abergavenny. Surname: Nevill. ABINGER Hereditary Baron in the Peerage of the United Kingdom: James Harry Lord Abinger. -

Elite Culture and the Decline of Scottish Jacobitism 1716-1745 Author(S): Margaret Sankey and Daniel Szechi Source: Past & Present, No

The Past and Present Society Elite Culture and the Decline of Scottish Jacobitism 1716-1745 Author(s): Margaret Sankey and Daniel Szechi Source: Past & Present, No. 173 (Nov., 2001), pp. 90-128 Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of The Past and Present Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3600841 Accessed: 02/07/2009 12:37 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=oup. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Oxford University Press and The Past and Present Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Past & Present. -

The Signatories: Hamilton

The signatories: Hamilton James Hamilton, 2d Marquis of Hamilton, was born in 1589 into the premier hereditary peerage of Scotland. The son of John, 1st Marquis of Hamilton, and Lady Margaret Lyon of Glamis, he was descended through his mother from the Scottish King Robert II (as well as being eventually related to Lady Elizabeth Bowes Lyon – our modern Queen Elizabeth’s “Queen Mum” – who grew up in Glamis Castle in the early years of the 20th century). He was descended, through his father, from several Scottish Kings, a shrewd series of dynastic alliances, including the marriage in 1474 of the 1st Lord Hamilton to a daughter of King James II, having made the Hamiltons one of Scotland’s most powerful families. For many years Hamilton’s grandfather, James Hamilton, 2nd Earl of Arran, was heir presumptive to the Scottish throne. If Mary Stuart (aka Mary Queen of Scots) had died without children, Arran would have succeeded her as king. Mary Stuart had ascended to the throne as an infant upon the death of her father, King James V of Scotland, in 1542. In March 1543, the Scottish Parliament appointed Arran the Lord Governor, or Regent, of Scotland. Arran has been variously described as faithless, inept, vacillating and indecisive. All agree that his overriding purpose in life was self-interest, occasionally broadening to include the advancement of his immediate family. As a Protestant lord, Arran proposed, first, the betrothal of the infant Queen Mary to his own son. When the other Scottish lords did not support him, he then proposed Mary’s betrothal to the 5-year-old son of Henry VIII. -

Cadzow Castle Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC115 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90342) Taken into State care: 1979 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2014 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE CADZOW CASTLE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2018 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH CADZOW CASTLE SYNOPSIS Cadzow Castle is located on a promontory overlooking the deeply wooded gorge of the Avon Water from its southern bank. On the opposite bank stands Châtelhérault (see below). -

Inventory Acc.12413 Lord James Douglas-Hamilton

Inventory Acc.12413 Lord James Douglas-Hamilton National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © Trustees of the National Library of Scotland Papers relating to the 10th and 11th Earls of Selkirk and the Selkirk peerage, 1945-2004 Deposited, October 2004 Not to be consulted without the permission of the owner, Lord Selkirk of Douglas (Lord James Douglas-Hamilton, who disclaimed the title of 11th Earl of Selkirk) Box 1 Papers relating to George, 10th Earl: 1 Documents on the earldom, 1945-1980 2 Family trees of the tenth earl 3 Papers on the earldom, 1945 4 Correspondence with Alasdair Douglas-Hamilton and lawyers on the earldom, 1965-1991 5 Letter of Lord Trenchard to the tenth earl, 10 July 1945, accompanying Trenchard’s pamphlet, The Principles of Air Power on War, 1945. Also a covering letter from the 14th Duke of Hamilton, 22 June 1965. Box 2 Papers relating to George, 10th Earl and James, 11th Earl: 1 Correspondence with Lord James Douglas-Hamilton, 1990-1994 2 Tributes to the tenth earl and his wife following their deaths in 1994. Material relating to their memorial service 3 Letter of Lee Kuan Yew, Prime Minister of Singapore, on the tenth earl, 22 May 1995, with photograph. Other miscellaneous letters and material on the Selkirk peerage 4 Correspondence and material on the succession to the Selkirk title, 1941-1991 5 Four legal opinions on the peerage succession and related material 6 Tenth earl’s opinion on the succession and legal opinions 7 Disclaimer of the Selkirk title by the 11th Earl, and related papers 8 Material relating to the draft Oxford Dictionary of National Biography articles on the 10th Earl and the 14th Duke of Hamilton, by Lord Selkirk of Douglas. -

Peerage of Great Britain

Page 1 of 5 Peerage of Great Britain From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Divisions of the Peerage The Peerage of Great Britain comprises all extant peerages created in the Kingdom of Great Britain after the Act of Union Peerage of England 1707 but before the Act of Union 1800. It replaced the Peerage of Scotland Peerages of England and Scotland, until it was itself replaced by the Peerage of the United Kingdom in 1801. Peerage of Ireland Until the passage of the House of Lords Act 1999, all Peers of Peerage of Great Britain Great Britain could sit in the House of Lords. Peerage of the United Kingdom The ranks of the Great British peerage are Duke, Marquess, Earl, Viscount and Baron. In the following table of Great British peers, higher or equal titles in the other peerages are listed. Contents 1 Dukes in the Peerage of Great Britain 2 Marquesses in the Peerage of Great Britain 3 Earls in the Peerage of Great Britain 4 Viscounts in the Peerage of Great Britain 5 Barons in the Peerage of Great Britain 6 See also Dukes in the Peerage of Great Britain Title Creation Other titles The Duke of Brandon 1711 Duke of Hamilton in the Peerage of Scotland The Duke of Manchester 1719 The Duke of Northumberland 1766 Marquesses in the Peerage of Great Britain Title Creation Other titles The Marquess of Lansdowne 1784 The Marquess Townshend 1787 The Marquess of Stafford 1786 Duke of Sutherland in the Peerage of the UK The Marquess of Salisbury 1789 The Marquess of Bath 1789 Viscount Weymouth in the Peerage of England; The Marquess of Abercorn