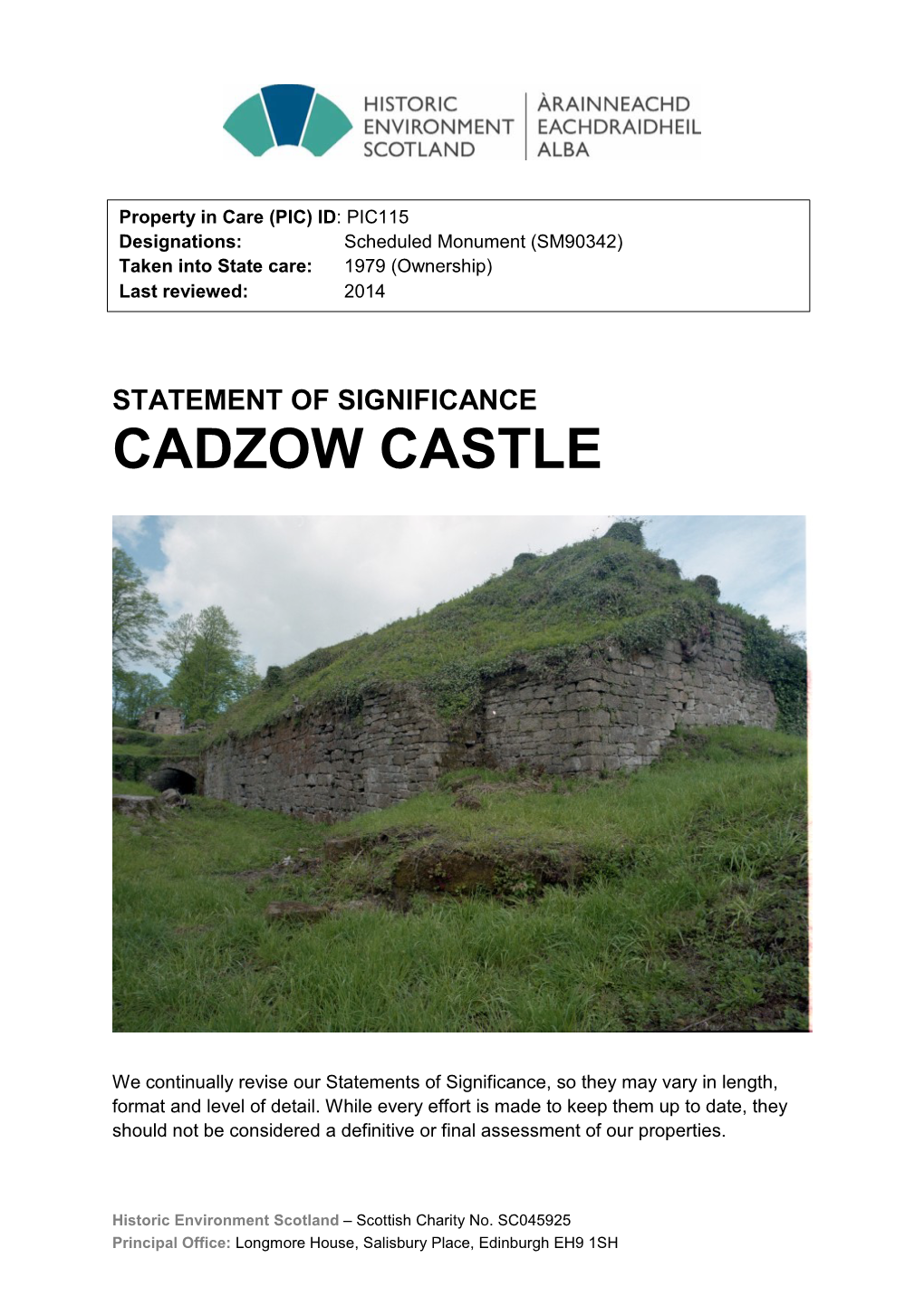

Cadzow Castle Statement of Significance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excavations at Craignethan Castle, 1984 and 1995 John Lewis*, Eoin Mcb Cox| & Helen Smith}

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 128 (1998), 923-936 Excavations at Craignethan Castle, 1984 and 1995 John Lewis*, Eoin McB Cox| & Helen Smith} ABSTRACT This report describes excavations carried out within the basement of the ruined north-east tower courtyard(1984)at and immediate levelthe to tower the east of house (1995) Craignethanat Castle. The former was originally a kitchen but was remodelled at some stage, perhaps to a brewhouse. There evidencewas that rangea buildingsof beenhad planned eastthe sidethe for of inner courtyard but that quite early in the development of the castle (built c 1530) it was abandoned in favourimpressivethe of tower house. project The funded was Historicby Scotlandits and predecessor, Historic Buildings Monuments.and INTRODUCTION Several accounts have been written of Craignethan Castle (including MacGibbon & Ross 1887; Simpson 1963; Maclvor 1977; and McKean 1995; but see also Pringle 1992) and these should be consulted for more detailed descriptions of the monument than can be included here. Nevertheless, briea f summar histors it architecturf d yo yan presenteds i e thin i s scenpapee th t ordeen ri se o rt for the excavations described within. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Craignethan Castle dates from around 1530 and was the brainchild of Sir James Hamilton of Finnart, the illegitimate son of James, first Earl of Arran and great-grandson of King James II. Finnart not only commissioned the building of the castle but, as one who was passionately interested in architecture (and indeed the future Master of the King's Works), took a very active interest in its construction. Finnart was executed for treason in 1540 and the castle eventually fell into the hands of his half-brother (also James), who was to become the second Earl of Arran and Regent of Scotland during the minority of Mary, Queen of Scots. -

Excavations at Bothwell Castle, North Lanarkshire

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 127 (1997), 687-695 Excavation t Bothwelsa l Castle, North Lanarkshire John Lewis* ABSTRACT The following report describes two small-scale excavations (in 1987-8 and 1991) within the castle enclosure and a watching brief carried out in 1993 during the topsail clearance which preceded the installation of a new car park some 100 m east of the castle. Trenching to the immediate east of the postern revealed traces of what may have been an extension to the south range; and a possible robber trench, perhaps associated with the gatehouse, was uncovered just inside the modern entrance to the castle. The project was funded by Historic Scotland (former SDD/HBM). INTRODUCTION Standin gwoodee th hig n ho d nort hRivee banth f rko outskirtClydee th towe n th o f , nf o so Uddingston and some 13 km south-east of Glasgow (illus 1), Bothwell Castle (NGR: NS 688 593) retains the air of the formidable stronghold that it once was (illus 2). Begun in the mid- or late 13th centur Waltey Williamyb n so f Mora s ro originae hi th r , yo l desigcastle neves th f enwa o r brought to fruition, probably because of the depredations of the Wars of Independence in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. It was not until the early 15th century, following many turbulent years during which the castle changed hands on several occasions, that the enclosure was finally completed somewhaa n the y o wore b ;s nth kwa t reduced scale from that originally conceived (Simpson 1958,14). -

The Four Iron Steamships of William Alexander Lewis Stephen Douglas – Hamilton

The Four Iron Steamships of William Alexander Lewis Stephen Douglas – Hamilton. KT 12th Duke of Hamilton, 9th Duke of Brandon, 2nd Duke of Châtellerault Second Edition. 1863 Easton Park, Suffolk, England (Demolished 1925) Hamilton Palace, Scotland (Demolished 1927) Brian Boon & Michel Waller Introduction The families residing in the village of Easton, Suffolk experienced many changing influences over their lives during the 92 year tenure of four generations of the Hamilton family over the 4,883 acre Easton Park Estate. The Dukes of Hamilton were the Premier Dukedom of Scotland, owning many mansions and estates in Scotland together with other mining interests. These generated considerable income. Hamilton Palace alone, in Scotland, had more rooms than Buckingham Palace. Their fortunes varied from the extremely wealthy 10th Duke Alexander, H.M. Ambassador to the Court of the Czar of Russia, through to the financial difficulties of the 12th Duke who was renowned for his idleness, gambling and luxurious lifestyle. Add to this the agricultural depression commencing in 1870. On his death in 1895, he left debts of £1 million even though he had previously sold the fabulous art and silver collections of his grandparents. His daughter, Mary, then aged 10 inherited Easton and the Arran estates and remained in Easton, with the Dowager Duchess until 1913 when she married Lord Graham. The estates were subsequently sold and the family returned to Arran. This is an account of the lives of the two passenger paddle steamers and two large luxury yachts that the 12th Duke had built by Blackwood & Gordon of Port Glasgow and how their purchase and sales fitted in with his varying fortunes and lifestyle. -

Hand-Book of Hamilton, Bothwell, Blantyre, and Uddingston. with a Directory

; Hand-Book HAMILTON, BOTHWELL, BLANTYRE, UDDINGSTON W I rP H A DIE EJ C T O R Y. ILLUSTRATED BY SIX STEEL ENGRAVINGS AND A MAP. AMUS MACPHERSON, " Editor of the People's Centenary Edition of Burns. | until ton PRINTED AT THE "ADVERTISER" OFFICE, BY WM. NAISMITH. 1862. V-* 13EFERKING- to a recent Advertisement, -*-*; in which I assert that all my Black and Coloured Cloths are Woaded—or, in other wards, based with Indigo —a process which,, permanently prevents them from assuming that brownish appearance (daily apparent on the street) which they acquire after being for a time in use. As a guarantee for what I state, I pledge myself that every piece, before being taken into stock, is subjected to a severe chemical test, which in ten seconds sets the matter at rest. I have commenced the Clothing with the fullest conviction that "what is worth doing is worth doing well," to accomplish which I shall leave " no stone untamed" to render my Establishment as much a " household word " ' for Gentlemen's Clothing as it has become for the ' Unique Shirt." I do not for a moment deny that Woaded Cloths are kept by other respectable Clothiers ; but I give the double assurance that no other is kept in my stock—a pre- caution that will, I have no doubt, ultimately serve my purpose as much as it must serve that of my Customers. Nearly 30 years' experience as a Tradesman has convinced " me of the hollowness of the Cheap" outcry ; and I do believe that most people, who, in an incautious moment, have been led away by the delusive temptation of buying ' cheap, have been experimentally taught that ' Cheapness" is not Economy. -

Introduction to the Abercorn Papers Adobe

INTRODUCTION ABERCORN PAPERS November 2007 Abercorn Papers (D623) Table of Contents Summary ......................................................................................................................2 Family history................................................................................................................3 Title deeds and leases..................................................................................................5 Irish estate papers ........................................................................................................8 Irish estate and related correspondence.....................................................................11 Scottish papers (other than title deeds) ......................................................................14 English estate papers (other than title deeds).............................................................17 Miscellaneous, mainly seventeenth-century, family papers ........................................19 Correspondence and papers of the 6th Earl of Abercorn............................................20 Correspondence and papers of the Hon. Charles Hamilton........................................21 Papers and correspondence of Capt. the Hon. John Hamilton, R.N., his widow and their son, John James, the future 1st Marquess of Abercorn....................22 Political correspondence of the 1st Marquess of Abercorn.........................................23 Political and personal correspondence of the 1st Duke of Abercorn...........................26 -

The History of Scotland from the Accession of Alexander III. to The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT LOS ANGELES THE GIFT OF MAY TREAT MORRISON IN MEMORY OF ALEXANDER F MORRISON THE A 1C MEMORIAL LIBRARY HISTORY OF THE HISTORY OF SCOTLAND, ACCESSION OF ALEXANDEB III. TO THE UNION. BY PATRICK FRASER TYTLER, ** F.RS.E. AND F.A.S. NEW EDITION. IN TEN VOLUMES. VOL. X. EDINBURGH: WILLIAM P. NIMMO. 1866. MUEKAY AND OIBB, PUINTERS. EDI.VBUKOII V.IC INDE X. ABBOT of Unreason, vi. 64 ABELARD, ii. 291 ABERBROTHOC, i. 318, 321 ; ii. 205, 207, 230 Henry, Abbot of, i. 99, Abbots of, ii. 206 Abbey of, ii. 205. See ARBROATH ABERCORN. Edward I. of England proceeds to, i. 147 Castle of, taken by James II. iv. 102, 104. Mentioned, 105 ABERCROMBY, author of the Martial Achievements, noticed, i. 125 n.; iv. 278 David, Dean of Aberdeen, iv. 264 ABERDEEN. Edward I. of England passes through, i. 105. Noticed, 174. Part of Wallace's body sent to, 186. Mentioned, 208; ii. Ill, n. iii. 148 iv. 206, 233 234, 237, 238, 248, 295, 364 ; 64, ; 159, v. vi. vii. 267 ; 9, 25, 30, 174, 219, 241 ; 175, 263, 265, 266 ; 278, viii. 339 ; 12 n.; ix. 14, 25, 26, 39, 75, 146, 152, 153, 154, 167, 233-234 iii. Bishop of, noticed, 76 ; iv. 137, 178, 206, 261, 290 ; v. 115, n. n. vi. 145, 149, 153, 155, 156, 167, 204, 205 242 ; 207 Thomas, bishop of, iv. 130 Provost of, vii. 164 n. Burgesses of, hanged by order of Wallace, i. 127 Breviary of, v. 36 n. Castle of, taken by Bruce, i. -

Monumental Guidebooks 'In State Care' R W Munro*

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 115 (1985), 3-14 Monumental guidebooks 'in State care' R W Munro* SUMMARY A new series of guidebooks to Scottish monuments in State care is being produced by the Historic Buildings and Monuments Directorate of the Scottish Development Department. The origin and progress Government-sponsoredof guidebooks Scotlandin consideredare chiefly from pointthe of view of the non-expert user or casual visitor. INTRODUCTION Five years is not a long time in the history of an ancient monument, but in that period there has bee transformationa whicy b y h visitorwa e th n historii o st Governmencn i sitew sno t car helpee ear d to understand what they see. A new series of guidebooks and guide-leaflets is part of the continuing proces f improveo s d 'presentation' whic bees hha n carrie t ove yeare dou th r s successivelM H y yb Office of Works, the Ministry of Works (later of Public Building and Works), the Department of the Environment finallSecretare d th an , y yb Statf yo Scotlanr efo d acting throug Scottise hth h Develop- ment Department. One does not need to be particularly 'ancient' to have seen that rather bewildering procession of office, ministr departmend yan t pas rapin si d order acros bureaucratie sth c stage. Only since 197s 8ha the Scottish ful e Officlth responsibilitd eha y for wha bees tha n called 'our monumental heritagea '- useful blanket term which appears to cover the definitions of 'monument' and 'ancient monument' enshrined in the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act of 1979 (Maclvor & Fawcett 1983, 20). -

THE LONDON Gfaz^TTE, JULY 5, 1904. 4237

THE LONDON GfAZ^TTE, JULY 5, 1904. 4237 ; '.' "• Y . ' '-Downing,Street. Charles, Earl of-Leitrim. '-'--•'. ' •' July 5, 1904. jreorge, Earl of Lucan. The KING has been pleased to approve of the Somerset Richard, Earl of Belmore. appointment of Hilgrpye Clement Nicolle, Esq. Tames Francis, Earl of Bandon. (Local Auditor, Hong Kong), to be Treasurer of Henry James, Earl Castle Stewart. the Island of Ceylon. Richard Walter John, Earl of Donoughmore. Valentine Augustus, Earl of Kenmare. • William Henry Edmond de Vere Sheaffe, 'Earl of Limericks : i William Frederick, Earl-of Claricarty. ''" ' Archibald Brabazon'Sparrow/Earl of Gosford. Lawrence, Earl of Rosse. '• -' • . ELECTION <OF A REPRESENTATIVE PEER Sidney James Ellis, Earl of Normanton. FOR IRELAND. - Henry North, -Earl of Sheffield. Francis Charles, Earl of Kilmorey. Crown and Hanaper Office, Windham Thomas, Earl of Dunraven and Mount- '1st July, 1904. Earl. In pursuance of an Act passed in the fortieth William, Earl of Listowel. year of the reign of His Majesty King George William Brabazon Lindesay, Earl of Norbury. the Third, entitled " An Act to regulate the mode Uchtef John Mark, Earl- of Ranfurly. " by which the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Jenico William Joseph, Viscount Gormanston. " the Commons, to serve ia the Parliament of the Henry Edmund, Viscount Mountgarret. " United Kingdom, on the part of Ireland, shall be Victor Albert George, Viscount Grandison. n summoned and returned to the said Parliament," Harold Arthur, Viscount Dillon. I do hereby-give Notice, that Writs bearing teste Aldred Frederick George Beresford, Viscount this day, have issued for electing a Temporal Peer Lumley. of Ireland, to succeed to the vacancy made by the James Alfred, Viscount Charlemont. -

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

THE GLADES at BOTHWELL Highest Standard of Design, Build and Finish in Prime Locations Throughout Central Scotland

building on firm foundations Mansion Kingdom Homes is dedicated to building exclusive homes to the THE GLADES at BOTHWELL highest standard of design, build and finish in prime locations throughout Central Scotland. We are a family run company that specialises in the construction of quality bespoke new build houses and custom luxury homes - the address, the life - and we are passionate about great design, sustainability of materials and quality of construction. Our team of highly skilled professionals and proven track record ensure the highest standards that gives us the ability to deliver Twelve bespoke townhouses delivering the height your bespoke dream home. of style in the heart of Bothwell. mansionkingdomhomes.co.uk 2 | THE GLADES AT BOTHWELL THE GLADES AT BOTHWELL | 3 some things are worth waiting for Here at The Glades, every space is considered. Every inch of the 4000 square feet of it. Thoughtful layouts. Intelligent design. Your new home boasts a prestigious pedigree based on the classic principles of luxury - timeless, sophisticated and understated. A modern expression of Bothwell sophistication. This is home life the way it was intended. The Glades provide abundant space, enhanced by expansive floor-to-ceiling views. Lofty ceilings, private terraces and generous living areas elevate a sense of endless sanctuary. Boasting four luxury bedrooms with en suite to master bedroom, gym room, cinema room, secluded garden and integral garage these are modern intelligent homes with refined qualities and impeccable standards designed for the 21st century living. CGI Illustration of proposed development. 4 | THE GLADES AT BOTHWELL THE GLADES AT BOTHWELL | 5 you are where you live The Glades at Bothwell has been designed and built to create simple, yet elegant and dynamic forms nestled within the wooded landscape at the end of Glebe Wynd. -

Clan Douglas

CLAN DOUGLAS ARMS Quarterly, 1st, Azure, a man’s heart ensigned of an Imperial Crown Proper and on a chief Azure three stars of the Field (Douglas) CREST A salamander Vert encircled with flames of fire Proper MOTTO Jamais arriére (Never behind) SUPPORTERS (on a compartment comprising a hillock, bounded by stakes of wood wreathed round with osiers) Dexter, a naked savage wreathed about the head and middle with laurel and holding a club erect Proper; sinister, a stag Proper, armed and unguled Or The Douglases were one of Scotland’s most powerful families. It is therefore remarkable that their origins remain obscure. The name itself is territorial and it has been suggested that it originates form lands b Douglas Water received by a Flemish knight from the Abbey of Kelso. However, the first certain record of the name relates to a William de Dufglas who, between 1175 and 1199, witnessed charter by the Bishop of Glasgow to the monks of Kelso. Sir William de Douglas, believed to be the third head of the Borders family, had two sons who fought against the Norse at the Battle of Largs in 1263. William Douglas ‘The Hardy’ was governor of Berwick when the town was besieged by the English. Douglas was taken prisoner when the town fell and he was only released when he agreed to accept the claim of Edward I of England to be overlord of Scotland. He later joined Sir William Wallace in the struggle for Scottish independence but he was again captured and died in England in 1302. -

Castle Collection

140 PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY, 1951-52. IX. SCOTTISH MEDIEVAL POTTERY E BOTHWELTH : L CASTLE COLLECTION. BY STEWART CRUDEN, F.S.A., A.R.I.B.A., F.S.A.Sco-r., Inspecto Ancienf ro t Monument Scotlandr sfo . Bothwell Castle is one of the largest and finest mediaeval castles surviving in Scotland. Documentary evidence implie existencs sit s 1278wa n ei t I . taken by the Scots in 1298—9 after a siege of fourteen months, recaptured by Edward in 1301, and held for the English until 1314 when, after Bannock- burn, it was surrendered to Edward Bruce and thereafter dismantled by him. There was a second English occupation from 1331 until 1337, when it was captured by Sir Andrew de Moray, to whom it rightfully belonged. Partially destroyed by him as a military expedient it lay waste until c. 1362, when a second reconstruction of the twice dismantled fabric took place. Much of the original 13th-century work remains; the 14th- and 15th-century works also surviv somn ei e considerable exten heightd an t . The clearance Ministr th e sity th b e f f Workseyo o , begu 1937-8n ni , produced the largest assemblage of mediaeval pottery yet recovered from a single sit Scotlandn ei . Fro greae mth t quantit fragmentf yo vessel3 s2 s have been completely restore mans a d yd an substantia l fragments reconstructed. The material speaks for itself, and without further argument establishes principae th l poin thif to s paper, viz. that ther Scotlann i s ei drepresentativa e collectio f mediaevao n l potter n considerabli y d hithertan e o unrecorded quantity, comparabl qualityn ei , variet artistid yan c interest wit more hth e widely-known collections at York, the British Museum and elsewhere in England.