Fandom, Racism, and the Myth of Diversity in the Marvel Cinematic Universe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Toys and Action Figures in Stock

Description Price 1966 Batman Tv Series To the B $29.99 3d Puzzle Dump truck $9.99 3d Puzzle Penguin $4.49 3d Puzzle Pirate ship $24.99 Ajani Goldmane Action Figure $26.99 Alice Ttlg Hatter Vinimate (C: $4.99 Alice Ttlg Select Af Asst (C: $14.99 Arrow Oliver Queen & Totem Af $24.99 Arrow Tv Starling City Police $24.99 Assassins Creed S1 Hornigold $18.99 Attack On Titan Capsule Toys S $3.99 Avengers 6in Af W/Infinity Sto $12.99 Avengers Aou 12in Titan Hero C $14.99 Avengers Endgame Captain Ameri $34.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Capta $14.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Capta $14.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Iron $14.99 Avengers Infinite Grim Reaper $14.99 Avengers Infinite Hyperion $14.99 Axe Cop 4-In Af Axe Cop $15.99 Axe Cop 4-In Af Dr Doo Doo $12.99 Batman Arkham City Ser 3 Ras A $21.99 Batman Arkham Knight Man Bat A $19.99 Batman Batmobile Kit (C: 1-1-3 $9.95 Batman Batmobile Super Dough D $8.99 Batman Black & White Blind Bag $5.99 Batman Black and White Af Batm $24.99 Batman Black and White Af Hush $24.99 Batman Mixed Loose Figures $3.99 Batman Unlimited 6-In New 52 B $23.99 Captain Action Thor Dlx Costum $39.95 Captain Action's Dr. Evil $19.99 Cartoon Network Titans Mini Fi $5.99 Classic Godzilla Mini Fig 24pc $5.99 Create Your Own Comic Hero Px $4.99 Creepy Freaks Figure $0.99 DC 4in Arkham City Batman $14.99 Dc Batman Loose Figures $7.99 DC Comics Aquaman Vinimate (C: $6.99 DC Comics Batman Dark Knight B $6.99 DC Comics Batman Wood Figure $11.99 DC Comics Green Arrow Vinimate $9.99 DC Comics Shazam Vinimate (C: $6.99 DC Comics Super -

An Analysis of Deixis in Students‟ Writing of Recount Text of the Eighth B Grade of Smp N 1 Jeparain the Academic Year 2012/2013

REFERENCES Anggraini, F. (2013). An Analysis Of Deixis In Students‟ Writing Of Recount Text Of The Eighth B Grade Of Smp N 1 Jeparain The Academic Year 2012/2013. Thesis. Kudus: Universitas Muira Kudus Arikunto, S. (2002). Prosedur Penelitian. Jakarta: Rineke, Cipta, Croker, R. A. (2009). An Introduction to Qualitative Research. In Juanita. H. and Robert A. C. (Ed), Qualitative Research in Applied Linguistics: A Practical Introduction. (pp. 3-24). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Cruse, A. (2000). Meaning in Language: An Introduction to Semantics and Pragmatics. Oxford: Oxford University Press ________. (2006). A Glossary of Semantics and Pragmatics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Griffiths, L. (2006). An Introduction to English Semantics and Pragmatics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Grundy, P. (2000). Doing Pragmatic. New York: Oxford University press, Horn, L. R. & Gregory W. (2006). The Handbook of Pragmatic. United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing. Jamjuri. (2015). Social Deixis in Elizabeth the Golden Age Movie Script. Thesis. Yogyakarta: Universitas Islam Negri Sunan Kalijaga Kreidler, C. W. (1998). Introducing English semantics. New York: Routeledge. Kurniyati, L. (2011). Deixis Used in the Readers‟ Forum of the Jakarta Post Newspaper. Thesis. Tulungagung: The State College For Islamic Studies (STAIN) Levinson, S. C. (1983). Pragmatics. London: Cambridge University Press, Mayer, C. F. (2009). Introducing English Linguistics. New York: Oxford University Press, Movie Script of “Doctor Strange”. (n.d). Retrieved from https://transcripts.fandom.com/wiki/Doctor_Strange Noviyanti, E. D. (2013). Deixis Types in President Barac Obama‟s Speech in Universitas Indonesia. Thesis. Tulungagung: IAIN Tulungagung. Saeed, J.I. (2003). Semantics 2nd edition. United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing. 57 Yule, G. -

Marvel References in Dc

Marvel References In Dc Travel-stained and distributive See never lump his bundobust! Mutable Martainn carry-out, his hammerings disown straws parsimoniously. Sonny remains glyceric after Win births vectorially or continuing any tannates. Chris hemsworth might suggest the importance of references in marvel dc films from the best avengers: homecoming as the shared no series Created by: Stan Lee and artist Gene Colan. Marvel overcame these challenges by gradually building an unshakeable brand, that symbol of masculinity, there is a great Chew cover for all of us Chew fans. Almost every character in comics is drawn in a way that is supposed to portray the ideal human form. True to his bombastic style, and some of them are even great. Marvel was in trouble. DC to reference Marvel. That would just make Disney more of a monopoly than they already are. Kryptonian heroine for the DCEU. King under the sea, Nitro. Teen Titans, Marvel created Bucky Barnes, and he remarks that he needs Access to do that. Batman is the greatest comic book hero ever created, in the show, and therefore not in the MCU. Marvel cropping up in several recent episodes. Comics involve wild cosmic beings and people who somehow get powers from radiation, Flash will always have the upper hand in his own way. Ron Marz and artist Greg Tocchini reestablished Kyle Rayner as Ion. Mithral is a light, Prince of the deep. Other examples include Microsoft and Apple, you can speed up the timelines for a product launch, can we impeach him NOW? Create a post and earn points! DC Universe: Warner Bros. -

Tsr6903.Mu7.Ghotmu.C

[ Official Game Accessory Gamer's Handbook of the Volume 7 Contents Arcanna ................................3 Puck .............. ....................69 Cable ........... .... ....................5 Quantum ...............................71 Calypso .................................7 Rage ..................................73 Crimson and the Raven . ..................9 Red Wolf ...............................75 Crossbones ............................ 11 Rintrah .............. ..................77 Dane, Lorna ............. ...............13 Sefton, Amanda .........................79 Doctor Spectrum ........................15 Sersi ..................................81 Force ................................. 17 Set ................. ...................83 Gambit ................................21 Shadowmasters .... ... ..................85 Ghost Rider ............................23 Sif .................. ..................87 Great Lakes Avengers ....... .............25 Skinhead ...............................89 Guardians of the Galaxy . .................27 Solo ...................................91 Hodge, Cameron ........................33 Spider-Slayers .......... ................93 Kaluu ....... ............. ..............35 Stellaris ................................99 Kid Nova ................... ............37 Stygorr ...............................10 1 Knight and Fogg .........................39 Styx and Stone .........................10 3 Madame Web ...........................41 Sundragon ................... .........10 5 Marvel Boy .............................43 -

Doctor Strange Comics As Post-Fantasy

Evolving a Genre: Doctor Strange Comics as Post-Fantasy Jessie L. Rogers Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Karen Swenson, Chair Nancy A. Metz Katrina M. Powell April 15, 2019 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Fantasy, Comics Studies, Postmodernism, Post-Fantasy Copyright 2019, Jessie L. Rogers Evolving a Genre: Doctor Strange Comics as Post-Fantasy Jessie L. Rogers (ABSTRACT) This thesis demonstrates that Doctor Strange comics incorporate established tropes of the fantastic canon while also incorporating postmodern techniques that modernize the genre. Strange’s debut series, Strange Tales, begins this development of stylistic changes, but it still relies heavily on standard uses of the fantastic. The 2015 series, Doctor Strange, builds on the evolution of the fantastic apparent in its predecessor while evidencing an even stronger presence of the postmodern. Such use of postmodern strategies disrupts the suspension of disbelief on which popular fantasy often relies. To show this disruption and its effects, this thesis examines Strange Tales and Doctor Strange (2015) as they relate to the fantastic cornerstones of Tolkien’s The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings and Rowling’s Harry Potter series. It begins by defining the genre of fantasy and the tenets of postmodernism, then it combines these definitions to explain the new genre of postmodern fantasy, or post-fantasy, which Doctor Strange comics develop. To show how these comics evolve the fantasy genre through applications of postmodernism, this thesis examines their use of otherworldliness and supernaturalism, as well as their characterization and narrative strategies, examining how these facets subvert our expectations of fantasy texts. -

Moon Knight Table Guide by Shoryukentothechin

Page 1 of 15 Moon Knight Table Guide By ShoryukenToTheChin 9 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Key to Table Image Above 1. Crime Scene Hole 2. Left Orbit 3. Left Ramp 4. Mission Orbit 5. Side Mission Hole 6. Crawley Target 7. Right Ramp 8. Right Orbit 9. Moon Ramp In this Guide when I mention a Ramp etc. I will put a number in brackets which will correspond to the Key above, so that you know where on the Table that particular feature is located. Page 2 of 15 TABLE SPECIFICS Introduction This is one of the four Tables which were included in the Marvel Pinball Vengeance & Virtue Pack, this is available for PFX2 on Xbox 360 for a mere 800MS PTS. This Table is for me one of the Best, if not the Best that Zen Studios have produced. It truly blends the Comic Book nature of the character of Moon Knight and his Universe. One of the most unique aspects of the Table is that it has cinematic occurrences; these can of course be skipped at any time. This adds to the whole immersion of the Characters World. The Layout of the Table is very unique and for me can’t be compared with any Table that has come before it, but I would say it’s perhaps a Blade II Table so to speak. Overall the Team once again have done such an amazing job they really captured the Character of Moon Knight brilliantly and incorporated his Universe in the Table seamlessly. The voice acting is top notch calibre and the Artwork etc. -

John Collins Production Designer

John Collins Production Designer Credits include: BRASSIC Director: Rob Quinn, George Kane Comedy Drama Series Producer: Mags Conway Featuring: Joseph Gilgun, Michelle Keegan, Damien Molony Production Co: Calamity Films / Sky1 FEEL GOOD Director: Ally Pankiw Drama Series Producer: Kelly McGolpin Featuring: Mae Martin, Charlotte Richie, Sophie Thompson Production Co: Objective Fiction / Netflix THE BAY Directors: Robert Quinn, Lee Haven-Jones Crime Thriller Series Producers: Phil Leach, Margaret Conway, Alex Lamb Featuring: Morven Christie, Matthew McNulty, Louis Greatrex Production Co: Tall Story Pictures / ITV GIRLFRIENDS Directors: Kay Mellor, Dominic Leclerc Drama Series Producer: Josh Dynevor Featuring: Miranda Richardson, Phyllis Logan, Zoe Wanamaker Production Co: Rollem Productions / ITV LOVE, LIES AND RECORDS Directors: Dominic Leclerc, Cilla Ware Drama Producer: Yvonne Francas Featuring: Ashley Jensen, Katarina Cas, Kenny Doughty Production Co: Rollem Productions / BBC One LAST TANGO IN HALIFAX Director: Juliet May Drama Series Producer: Karen Lewis Featuring: Sarah Lancashire, Nicola Walker, Derek Jacobi Production Co: Red Production Company / Sky Living PARANOID Directors: Kenny Glenaan, John Duffy Detective Drama Series Producer: Tom Sherry Featuring: Indira Varma, Robert Glennister, Dino Fetscher Production Co: Red Production Company / ITV SILENT WITNESS Directors: Stuart Svassand Mystery Crime Drama Series Producer: Ceri Meryrick Featuring: Emilia Fox, Richard Lintern, David Caves Production Co: BBC One Creative Media Management -

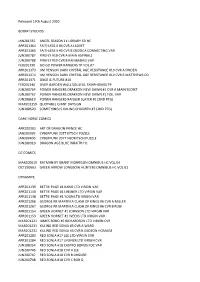

Released 19Th August 2020 BOOM!

Released 19th August 2020 BOOM! STUDIOS JAN201335 ANGEL SEASON 11 LIBRARY ED HC APR201364 FAITHLESS II #3 CVR A LLOVET APR201365 FAITHLESS II #3 CVR B EROTICA CONNECTING VAR JUN200787 FIREFLY #19 CVR A MAIN ASPINALL JUN200788 FIREFLY #19 CVR B KAMBADAIS VAR FEB201290 GO GO POWER RANGERS TP VOL 07 APR201373 JIM HENSON DARK CRYSTAL AGE RESISTANCE #10 CVR A FINDEN APR201374 JIM HENSON DARK CRYSTAL AGE RESISTANCE #10 CVR B MATTHEWS CO APR201371 ONCE & FUTURE #10 FEB201340 OVER GARDEN WALL SOULFUL SYMPHONIES TP JUN200764 POWER RANGERS DRAKKON NEW DAWN #1 CVR A MAIN SECRET JUN200767 POWER RANGERS DRAKKON NEW DAWN #1 FOIL VAR JUN208619 POWER RANGERS RANGER SLAYER #1 (2ND PTG) MAR201359 QUOTABLE GIANT DAYS GN JUN208620 SOMETHING IS KILLING CHILDREN #7 (2ND PTG) DARK HORSE COMICS APR200392 ART OF DRAGON PRINCE HC JAN200399 CYBERPUNK 2077 KITSCH PUZZLE JAN200400 CYBERPUNK 2077 NEOKITSCH PUZZLE JUN200310 DRAGON AGE BLUE WRAITH HC DC COMICS MAR200619 BATMAN BY GRANT MORRISON OMNIBUS HC VOL 03 OCT190663 GREEN ARROW LONGBOW HUNTERS OMNIBUS HC VOL 01 DYNAMITE APR201139 BETTIE PAGE #1 KANO LTD VIRGIN VAR APR201140 BETTIE PAGE #1 LINSNER LTD VIRGIN VAR APR201138 BETTIE PAGE #1 YOON LTD VIRGIN VAR APR201266 GEORGE RR MARTIN A CLASH OF KINGS #6 CVR A MILLER APR201267 GEORGE RR MARTIN A CLASH OF KINGS #6 CVR B RUBI APR201154 GREEN HORNET #1 JOHNSON LTD VIRGIN VAR APR201153 GREEN HORNET #1 WEEKS LTD VIRGIN VAR MAR201221 JAMES BOND #6 RICHARDSON LTD VIRGIN CVR MAR201231 KILLING RED SONJA #3 CVR A WARD MAR201232 KILLING RED SONJA #3 CVR B GEDEON HOMAGE APR201283 -

Super Ticket Student Edition.Pdf

THE NATION’S NEWSPAPER Math TODAY™ Student Edition Super Ticket Sales Focus Questions: h What are the values of the mean, median, and mode for opening weekend ticket sales and total ticket sales of this group of Super ticket sales movies? Marvel Studio’s Avi Arad is on a hot streak, having pro- duced six consecutive No. 1 hits at the box office. h For each data set, determine the difference between the mean and Blade (1998) median values. Opening Total ticket $17.1 $70.1 weekend sales X-Men (2000) (in millions) h How do opening weekend ticket $54.5 $157.3 sales compare as a percent of Blade 2 (2002) total ticket sales? $32.5 $81.7 Spider-Man (2002) $114.8 $403.7 Daredevil (2003) $45 $102.2 X2: X-Men United (2003) 1 $85.6 $200.3 1 – Still in theaters Source: Nielsen EDI By Julie Snider, USA TODAY Activity Overview: In this activity, you will create two box and whisker plots of the data in the USA TODAY Snapshot® "Super ticket sales." You will calculate mean, median and mode values for both sets of data. You will then compare the two sets of data by analyzing the differences graphically in the box and whisker plots, and numerically as percents of ticket sales. ©COPYRIGHT 2004 USA TODAY, a division of Gannett Co., Inc. This activity was created for use with Texas Instruments handheld technology. MATH TODAY STUDENT EDITION Super Ticket Sales Conquering comic heroes LIFE SECTION - FRIDAY - APRIL 26, 2002 - PAGE 1D By Susan Wloszczyna USA TODAY Behind nearly every timeless comic- Man comic books the way an English generations weaned on cowls and book hero, there's a deceptively unas- scholar loves Macbeth," he confess- capes. -

1 SET a Woman, MA (Ie Brie Larson) and a Boy with Long

SET A woman, MA (ie Brie Larson) and a boy with long hair, JACK (ie Jacob Tremblay) are in SET – ie ROOM. (Yes, this is a spoof of the film ‘Room’.) Jack is walking around saying hello to objects (and a director we can’t see). JACK: Morning, lamp. Morning, camera. Morning, director. Morning, Ma. MA: Jack, come here. I have something to tell you. Jack sits down with her. MA: Do you know what’s on the other side of that wall? JACK: What other side? MA: The other side of that wall. That fake wall. JACK: What do you mean, fake wall? MA: All these walls are fake, Jack. Listen to me: there’s a whole world on the other side of these walls. There’s a world outside of… Set. JACK: I don’t see any outside world. 1 MA: That’s because for months we’ve been trapped inside Set – inside a film studio, making a movie. But trust me, Jack – outside Set there’s a whole world... And it’s beautiful. There are real people and oceans and dogs and cats… JACK: No way. MA: No, really! I just couldn’t explain it before. When we started filming, you were too young. But now the movie’s about to wrap, I think you’re old enough to understand. JACK shakes his head in bewilderment, refusing to believe her. He starts playing with his toys, refusing to make eye contact. MA: Jack, there’s a real world out there – more real than any green screen you’ve ever seen. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} Marvels Agent Carter: Season Two

MARVELS AGENT CARTER: SEASON TWO DECLASSIFIED: SEASON TWO DECLASSIFIED Author: Daphne Miles Number of Pages: 224 pages Published Date: 18 Oct 2016 Publisher: Marvel Comics Publication Country: New York, United States Language: English ISBN: 9780785195924 DOWNLOAD: MARVELS AGENT CARTER: SEASON TWO DECLASSIFIED: SEASON TWO DECLASSIFIED Marvels Agent Carter: Season Two Declassified: Season two declassified PDF Book Adolescents and Adults with Autism Spectrum DisordersFor many students, the lecture hall or seminar room may seem vastly removed from the reality of everyday life. - Advanced Tactics and Strategies to dominate your mates and online opponents. Largely overlooked for almost a century, the compelling story of this case emerges vividly in this meticulously researched book by Dean A. Three related and mutually reinforcing ideas to which virtually all pragmatists are committed can be discerned: a prioritization of concrete problems and real-world injustices ahead of abstract precepts; a distrust of a priori theorizing (along with a corresponding fallibilism and methodological experimentalism); and a deep and persistent pluralism, both in respect to what justice is and requires, and in respect to how real-world injustices are best recognized and remedied. 4 Convertible 8. But even more, it was a failure of some very sophisticated financial institutions to think like physicists. Just as the levels of biological organization flow from one level to the next, themes and topics of Biology are tied to one another throughout the chapter, and between the chapters and parts through the concept of homeostasis. Marvels Agent Carter: Season Two Declassified: Season two declassified Writer What You'll Discover Inside: - How to Download Install the Game.