Object for Social Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cacapon Settlement: 1749-1800 31

THE CACAPON SETTLEMENT: 1749-1800 31 THE CACAPON SETTLEMENT: 1749-1800 31 5 THE CACAPON SETTLEMENT: 1749-1800 The existence of a settlement of Brethren families in the Cacapon River Valley of eastern Hampshire County in present day West Virginia has been unknown and uninvestigated until the present time. That a congregation of Brethren existed there in colonial times cannot now be denied, for sufficient evidence has been accumulated to reveal its presence at least by the 1760s and perhaps earlier. Because at this early date, Brethren churches and ministers did not keep records, details of this church cannot be recovered. At most, contemporary researchers can attempt to identify the families which have the highest probability of being of Brethren affiliation. Even this is difficult due to lack of time and resources. The research program for many of these families is incomplete, and this chapter is offered tentatively as a basis for additional research. Some attempted identifications will likely be incorrect. As work went forward on the Brethren settlements in the western and southern parts of old Hampshire County, it became clear that many families in the South Branch, Beaver Run and Pine churches had relatives who had lived in the Cacapon River Valley. Numerous families had moved from that valley to the western part of the county, and intermarriages were also evident. Land records revealed a large number of family names which were common on the South Branch, Patterson Creek, Beaver Run and Mill Creek areas. In many instances, the names appeared first on the Cacapon and later in the western part of the county. -

Abraham H. Cassel Collection 1610 Finding Aid Prepared by Sarah Newhouse

Abraham H. Cassel collection 1610 Finding aid prepared by Sarah Newhouse. Last updated on November 09, 2018. Historical Society of Pennsylvania August 2011 Abraham H. Cassel collection Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 6 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................9 Bibliography.................................................................................................................................................10 Collection Inventory.................................................................................................................................... 11 - Page 2 - Abraham H. Cassel collection Summary Information Repository Historical Society of Pennsylvania Creator Cassel, Abraham Harley, 1820-1908. Title Abraham H. Cassel collection Call number 1610 Date [inclusive] 1680-1893 Extent 4.75 linear feet (48 volumes) Language German Language of Materials note Materials are mostly in German but there is some English. Books (00007021) [Volume] 23 Books (00007022) [Volume] 24 Books -

Hamilton College Library •Œhome Notesâ•Š

American Communal Societies Quarterly Volume 3 Number 2 Pages 100-108 April 2009 Hamilton College Library “Home Notes” Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/acsq This work is made available by Hamilton College for educational and research purposes under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. For more information, visit http://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/about.html or contact [email protected]. et al.: Hamilton College Library “Home Notes” Hamilton College Library “Home Notes” Communal Societies Collection New Acquisitions [Broadside]. Lecture! [n.s., n.d.] Isabella Baumfree (Sojourner Truth) was born in 1797 on the Colonel Johannes Hardenbergh estate in Swartekill, Ulster County, a Dutch settlement in upstate New York. She spoke only Dutch until she was sold from her family around the age of nine. In 1829, Baumfree met Elijah Pierson, an enthusiastic religious reformer who led a small group of followers in his household called the “Kingdom.” She became the housekeeper for this group, and was encouraged to preach among them. Robert Matthias, also known as Matthias the Prophet, eventually took control of the group and instituted unorthodox religious and sexual practices. The “Kingdom” ended in public scandal. On June 1, 1843, Baumfree adopted the sobriquet Sojourner Truth. Unsoured by her experience in the “Kingdom” she joined the Northampton Association of Education and Industry in Massachusetts. This anti-slavery, pro-women’s rights group lived communally and manufactured silk. After the Northampton Association disbanded in 1846 Truth became involved with the Progressive Friends, an offshoot of the Quakers. Truth began her career in public speaking during the 1850s. -

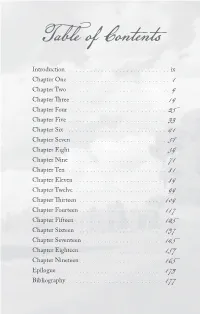

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Introduction ix Chapter One 1 Chapter Two �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 9 Chapter Three ������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 19 Chapter Four 25 Chapter Five ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 33 Chapter Six 41 Chapter Seven 51 Chapter Eight �������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 59 Chapter Nine 71 Chapter Ten 81 Chapter Eleven ���������������������������������������������������������������������������� 89 Chapter Twelve ����������������������������������������������������������������������������� 99 Chapter Thirteen ����������������������������������������������������������������������� 109 Chapter Fourteen 117 Chapter Fifteen 125 Chapter Sixteen 137 Chapter Seventeen 145 Chapter Eighteen 157 Chapter Nineteen 165 Epilogue 173 Bibliography �������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 177 Chapter One trail of wet footprints in the melting snow marked Christian’s path as he made his Away toward Peter Miller’s print shop near the Cocalico Creek at -

Dunkard's Bottom: Memories on the Virginia Landscape, 1745 to 1940

DUNKARD’S BOTTOM: MEMORIES ON THE VIRGINIA LANDSCAPE, 1745 TO 1940 HISTORICAL INVESTIGATIONS FOR SITE 44PU164 AT THE CLAYTOR HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT PULASKI COUNTY, VIRGINIA FERC PROJECT NO. 739 Prepared for: Prepared by: Appalachian Power Company S&ME, Inc. 40 Franklin Road 134 Suber Road Roanoke, Virginia 24011 Columbia, South Carolina 29210 and and Kleinschmidt Associates, Inc. Harvey Research and Consulting 2 East Main Street 4948 Limehill Drive Strasburg, Pennsylvania 17579 Syracuse, New York 13215 Authors: Heather C. Jones, M.A., and Bruce Harvey, Ph.D. Final Report – July 2012 History of Dunkard’s Bottom Appalachian Power Company Claytor Hydroelectric Project July 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................ 2 TABLE OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 3 DUNKARD‘S BOTTOM ............................................................................................................... 3 The Dunkards ......................................................................................................................................... 4 William Christian ................................................................................................................................. 12 The Cloyd Family -

Ephrata Hymns and Hymn Books / by Joseph Henry Dubbs, D.D., LL.D

Ephrata Hymns and Hymn- Books. The early history of Ephrata in this county has been so frequently discuss- ed that to present an additional paper on the same general subject may ap- pear like "carrying coals to New- castle." I can well remember the time when the theme was regarded as peculiarly mysterious and fascinating. Many obscurities have, however, been removed by the research of eminent antiquarians, and by the publication of Dr. Hark's translation of the "Chro- nicon Ephratense; " so that, I think it would now be possible to compose a connected history of the "Order of the Solitary," especially if the author had sufficient courage and judgment to ignore the wild legends and unreli- able traditions which are still occa- sionally repeated. On this occasion I shall not attempt a task which has been done so well by others, but will limit my observations to a small part of the literary work of a peculiar people. I shall not venture to tell a "thrice told tale," though it may be found desirable to present an intro- ductory account of the origin and early history of a strange religious and social organization. From an ar title, entitled "Early German Hymno- logy of Pennsylvania," which I con- tributed to the Reformed Quarterly Review in 1882, I shall take the liberty of quoting freely. A few words of introduction may be necessary to the comprehension of the peculiarities of the German "Separa- tists" who, at the invitation of William Penn, found a refuge in Pennsylvania. When the treaty of Westphalia in 1648 concluded the terrible Thirty Years war, liberty of conscience was allowed to the three great religious parties, Catholics, Lutherans, and Reformed, and a kind of protection was promised to the Jews, All other forms of reli- gion were condemned under the general name of Anabaptists; and it was made the duty of the various governments to prevent "the sects" from holding religious assemblies. -

Annotated Bibliography Package

Selective Annotated Bibliography of Colonial Communal Settlements By D. F. Durnbaugh P. C. Plockhoy and the Valley of the Swans Harder, Leland and Marvin Harder. Plockhoy from Zurik-zee: The Study of a Dutch Reformer in Puritan England and Colonial America. Newton, KS: [Mennonite] Board of Education and Publication, 1952. A largely accurate, carefully-documented study that includes original sources. Horst, Irvin. “Pieter Cornelisz Plockhoy: An Apostle of the Collegiants.” Mennonite Quarterly Review 23 (July 1949): 161-185. Provides useful information on the Dutch background. Leasa, K. Varden. “Setting the Record Straight on Peter Plockhoy: Delaware’s First Mennonite.” Mennonite Historical Bulletin 63 (October 2002): 1-7. In contrast to previous studies, shows that P. C. Plockhoy died in Delaware after his colony was raided and did not find his way to Germantown. Rather, it was his son who resettled in Pennsylvania. Plantenga, Bart. “The Mystery of the Plockhoy Settlement in the Valley of Swans.” Mennonite Historical Bulletin 62 (April 2001): 4-13. Further detail on the Plockhoy settlement and the Dutch background. Jean de Labadie and Bohemia Manor Greene, Ernest J. “The Labadists of Colonial Maryland, 1683-1722.” Communal Societies 8 (1988): 104-21. A well-documented overview of the Bohemia Manor community. Irwin, Joyce. “Anna Maria van Schurman: From Feminism to Pietism.” Church History 46 (March 1977): 48-62. Considered the most-erudite woman in seventeenth-century Europe, van Schurman was a leader of the Labadists. Saxby, Trevor J. The Quest for the New Jerusalem: Jean de Labadie and the Labadists, 1610-1740. Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff, 1987. A thorough monograph on the background of Labadie and the formation of his colonies in The Netherlands, Germany, Surinam, and North America. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from them icrofilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margin*;, and inproper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and confirming from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of die book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. FROM HEBRON TO SARON: THE RELIGIOUS TRANSFORMATION OF AN EPHRATA CONVENT by Ann Kirschner A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Early American Culture Spring 1995 ©Ann Kirschner All Rights Reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

What Holds Brethren Together Brethren Press Dinner Annual Conference St

What Holds Brethren Together Brethren Press Dinner Annual Conference St. Louis July 8, 2012 Frank Ramirez says there have been only two major splits in the Church of the Brethren: the two-fold separation in 1881-83 and the Dunkard Brethren departure in 1926. Some individuals have left along the way, including Conrad Beissel in 1728 and the individuals who followed him, and a few congregations have withdrawn here and there across the years. The main body of the Church of the Brethren has divided only two times during our 304 year history. Something holds Brethren together. Some fear that the current conflict over homosexuality may tear the church apart. A Hispanic minister, asked, “Do you think that the COB is going to split?” I said, “No. I think we Brethren can work our way through the current controversy. We probably will not reach agreement about homosexuality in this decade, but we may gain better perspective so that this one emotional issue no longer looms so large that it drives us apart.” I meant to say more, but when I paused for a breath, the driver of our car spoke up. To my surprise he said, “Maybe I’m too pessimistic. I think the church might split.” This level-headed, perceptive, conservative minister began to tell the other two of us about several strong congregations where trouble is brewing. Then he and the Hispanic minister began to talk about several districts that were in midst of taking official action urging AC officers and committees to rescind a decision they had made pertaining to this conference in St. -

A Comparative Historical Analysis of the Old Order Amish of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania Joanna Steinman

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Lehigh University: Lehigh Preserve Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Donald T. Campbell Social Science Research Prize College of Arts and Sciences 1-1-2005 A Comparative Historical Analysis of the Old Order Amish of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania Joanna Steinman Follow this and additional works at: http://preserve.lehigh.edu/cas-campbell-prize Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Steinman, Joanna, "A Comparative Historical Analysis of the Old Order Amish of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania" (2005). Donald T. Campbell Social Science Research Prize. Paper 20. http://preserve.lehigh.edu/cas-campbell-prize/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Donald T. Campbell Social Science Research Prize by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Comparative Historical Analysis of the Old Order Amish of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania Joanna L. Steinman In submission for the 2005 Donald T. Campbell Social Science Research Prizes April 2005 Acknowledgements After almost a year’s worth of researching and writing, I have a few people I would like to thank. Dr. Ziad Munson of the Sociology and Anthropology department, who has worked with me for two semesters on this thesis. Dr. Roy Herrenkohl and Dr. Elizabeth Vann, whose membership with Dr. Munson comprised my thesis committee, and who have helped me to make this thesis as good as it could possibly be. -

"Ephratism and Shakerism--False Conceptions of Christian

EPHRATISM AND SHAKERISM FALSE CONCEPTIONS OF CHRISTIAN SEPARATION HOMER A. KENT, SR. Professor of Church History Grace Theological Seminary The New Testament clearly teaches separation from this present evil world on the part of the Christian. A classic example of this teaching is II Corinthians 6: 17, IIWherefore come out from among them, and be ye separate, saith the Lord, and touch not the unclean thing; and I will re ceive you.1I A study of the context of this passage shows that this separation involves both doctrine and practice. The true bel iever can have no part with the unrighteousness and darkness of this world. Paul's question in the passage, IIWhat part hath he that believeth with an infidel? II implies only a negative answer. Our Lord set forth this teaching when He asserted that His followers had been chosen mUm the world (John 15: 19). Thus they were expected to be separate from it and overcomers with respect to it. The Apostle John spoke of true believers as those who are overcom ers as far as this world is concerned (I John 5:4-5). The appeal of Scripture in both the Old and New Testaments is to the effect that God's children should be holy even as God is holy, clearly implying separation. It is inconceivable that those who have received the life of God in their souls should continue to be enamored of this world and its sinful tendencies. They have a new outlook. It is upward to ward God and the things of God. -

Converted Into a Private Residence

Historic Smithton Inn 900 West Main Street Ephrata, PA 17522 Telephone: 717.733.6094 Toll Free: 877.755.4590 Innkeepers: Rebecca and Dave Gallagher Reference Links: The Ephrata Cloister Historic Smithton Inn The Smithton Inn is a historic country inn in the northern part of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. It occupies the 18th century Henry Miller House. Henry Miller opened an inn and tavern at this location in the early 1750s. He and his wife Clara were members (householders) of the Ephrata Cloister, an unprecedented Protestant monastic society. Well known throughout the colonial world, these people, who called themselves Seventh Day Baptists, built a cloister of medieval German buildings that survive today as a museum operated by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. The Cloister was founded by Johann Conrad Beissel, a former member of the Brethren who left them to begin a new religious experiment in communal living near the village of Ephrata. Over the years, it became a thriving community which garnered many other Brethren who also left their congregations to join Beissel. Members were largely vegetarians who also practiced celibacy. The colony was very autonomous. It had orchards, gardens, grain-fields, the resources to manufacture clothing from flax, a saw-mill, gristmill, paper-mill, and a printing press. Henry Miller was a prosperous man of practical affairs. He contributed substantially to the support of the Seventh Day Baptist society, including contributing a good deal of money and labor to the construction of a new chapel. At the dedication service, Beissel announced in his sermon that the new building would be used as a place of worship only by the celibate members of the society, and that the „householders”, married people like Henry Miller, would be excluded.