The XXX Test Glen Fuller

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abel Ferrara

A FILM BY Abel Ferrara Ray Ruby's Paradise, a classy go go cabaret in downtown Manhattan, is a dream palace run by charismatic impresario Ray Ruby, with expert assistance from a bunch of long-time cronies, sidekicks and colourful hangers on, and featuring the most beautiful and talented girls imaginable. But all is not well in Paradise. Ray's facing imminent foreclosure. His dancers are threatening a strip-strike. Even his brother and financier wants to pull the plug. But the dreamer in Ray will never give in. He's bought a foolproof system to win the Lottery. One magic night he hits the jackpot. And loses the ticket... A classic screwball comedy in the madcap tradition of Frank Capra, Billy Wilder and Preston Sturges, from maverick auteur Ferrara. DIRECTOR’S NOTE “A long time ago, when 9 and 11 were just 2 odd numbers, I lived above a fire house on 18th and Broadway. Between the yin and yang of the great Barnes and Noble book store and the ultimate sports emporium, Paragon, around the corner from Warhol’s last studio, 3 floors above, overlooking Union Square. Our local bar was a gothic church made over into a rock and roll nightmare called The Limelite. The club was run by a gang of modern day pirates with Nicky D its patron saint. For whatever reason, the neighborhood became a haven for topless clubs. The names changed with the seasons but the core crews didn't. Decked out in tuxes and razor haircuts, they manned the velvet ropes that separated the outside from the in, 100%. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

SEAN FADEN VFX Supervisor Seanfaden.Com

SEAN FADEN VFX Supervisor seanfaden.com PROJECTS DIRECTORS PRODUCERS/STUDIOS LADY AND THE TRAMP VFX Supervisor Charlie Bean Walt Disney Pictures MULAN VFX Supervisor Niki Caro Walt Disney Pictures POWER RANGERS Dean Israelite Marty Bowen, Wyck Godfrey VFX Supervisor, 2nd Unit Director Brent O’Connor / Lionsgate / Temple Hill FANTASTIC FOUR (Pixomondo) Josh Trank 20th Century Fox SLEEPY HOLLOW Season 2 (Pixomondo) Various Directors Marc Alpert, Dennis Hammer 20th Century Fox SCORPION Pilot (Pixomondo) Justin Lin Don Tardino, Clayton Townsend / CBS GAME OF THRONES Season 3 (Pixomondo) Various Directors HBO VFX Supervisor, 2nd Unit Director Nomination - VES Award WANDA RIDE FILM (Pixomondo) Aerial Unit Director FAST & FURIOUS 6 (Pixomondo) Justin Lin Universal Pictures A GOOD DAY TO DIE HARD (Pixomondo) John Moore 20th Century Fox VFX Supervisor, On-set VFX Supervisor A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET (Method Studios) Samuel Bayer New Line Cinema VFX Supervisor, On-set VFX Supervisor, 2nd Unit Director PERCY JACKSON & THE OLYMPIANS: Chris Columbus Fox 2000 THE LIGHTNING THIEF (Method Studios) LET ME IN (Method Studios) Matt Reeves Overture Films VFX Supervisor, On-set VFX Supervisor A LITTLE BIT OF HEAVEN Nicole Kassell Davis Entertainment (Method Studios) The Weinstein Company GULLIVER’S TRAVELS Rob Letterman 20th Century Fox (Method Studios) LOCKE & KEY Pilot (Method Studios) Mark Romanek Dimension Films VFX Supervisor, On-set VFX Supervisor CAPTAIN AMERICA: THE FIRST AVENGER Joe Johnston Paramount (Method Studios) THE GIRL WITH THE DRAGON TATOO David Fincher Columbia Pictures (Method Studios) THE PURGE (Method Studios) James DeMonaco Blumhouse / Universal Pictures VFX Supervisor, On-set VFX Supervisor ARTHUR NEWMAN GOLF PRO (Method Studios) Dante Ariola Vertebra Films TERMINATOR: SALVATION (Asylum) McG Warner Bros. -

Mattel Films to Develop Rock 'Em Sock '

Mattel Films to Develop Rock ‘Em Sock ‘Em Robots Live-Action Motion Picture with Universal Pictures and Vin Diesel’s One Race Films April 19, 2021 Vin Diesel also to star in the film, written by Ryan Engle, based on the classic tabletop game about battling robots EL SEGUNDO, Calif.--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Apr. 19, 2021-- Mattel, Inc. (NASDAQ: MAT) announced today plans to develop Rock ‘Em Sock ‘Em Robots®, the classic tabletop game featuring battling robots, into a live-action motion picture. Mattel Films is working with Universal Pictures and Vin Diesel’s production company, One Race Films, on the project. Diesel will also star in the film. This press release features multimedia. View the full release here: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20210419005111/en/ Mattel Films will produce the project alongside Diesel and Samantha Vincent (“The Fast and the Furious” franchise) from One Race Films. Ryan Engle (“Rampage,” “The Commuter”) penned the screenplay for the action adventure, which follows a father and son who form an unlikely bond with an advanced war machine. Kevin McKeon will lead the project for Mattel Films. “To take the classic Rock 'Em Sock 'Em game, with Mattel as my partner, and align it with the kind of world building, franchise making success we have had with Universal, is truly exciting," said Vin Diesel. “We are proud to bring this iconic piece of Mattel IP to life on the big screen with our tremendously talented partners Vin Diesel, One Race Films and Universal,” added Robbie Brenner, executive producer of Mattel Films. “Our rich library of franchises continues to yield compelling stories and (Graphic: Business Wire) we look forward to creating what is sure to be a thrilling action adventure for the whole family to enjoy with Rock ‘Em Sock ‘Em Robots.” Launched in 1966, the Rock ‘Em Sock ‘Em Robots game was inspired by an arcade boxing game which pitted Red Rocker® against Blue Bomber® in a fight to knock his rival’s block off. -

Stan Shaw Theatrical Resume

Stan Shaw SAG/AFTRA TELEVISION Criminal Minds Guest Star CBS Code Black Guest Star CBS CSI: Crime Scene Investigation Guest Star CBS Rag and Bone Guest Star Columbia TriStar Television The X-Files Guest Star FOX Freedom Song Supporting TNT Early Edition Guest Star CBS Murder, She Wrote Recurring Guest Star CBS Heaven & Hell: North & South, Book III Recurring Guest Star ABC Matlock Guest Star NBC Lifepod Guest Star FOX When Love Kills: The Seduction of John Hearn Supporting CBS L.A. Law Recurring Guest Star NBC Midnight Caller Recurring Guest Star NBC The Court-Martial of Jackie Robinson Guest Star TNT Wiseguy Recurring Guest Star CBS The Young Riders Guest Star ABC Red River Guest Star CBS The Three Kings Supporting ABC Billionaire Boys Club Supporting NBC Samaritan: The Mitch Snyder Story Supporting CBS Under Siege Supporting NBC The Gladiator Guest Star ABC Fame Guest Star NBC Hill Street Blues Guest Star NBC When Dreams Come True Guest Star ABC American Playhouse: Displaced Person Guest Star PBS Maximum Security Guest Star HBO The Mississippi Guest Star CBS Matt Houston Guest Star ABC Venice Medical Guest Star Doug Cramer, Exec. Prod. Darkroom Guest Star ABC Scared Straight! Another Story Guest Star CBS Buffalo Soldiers Guest Star NBC Roots: The Next Generation Guest Star ABC Arthur Hailey's The Moneychangers Guest Star NBC Street Killing Guest Star ABC FILM Jeepers Creepers 3 Lead Victor Salva Drive Me To Vegas and Mars Lead Sidney Furie Detonator Lead Jonathan Freedman Snake Eyes Lead Brian De Palma Daylight Lead Rob Cohen Cutthroat Island Lead Renny Harlin Houseguest Lead Randall Miller Rising Sun Lead Philip Kaufman Body of Evidence Lead Uli Edel Fried Green Tomatoes Lead Jon Avnet Fear Lead Rockne S. -

Conclusion: What Might a War Film Look Like Going Forward?

CONCLUSION: WHAT MIGHT A WAR FILM LOOK LIKE GOING FORWARD? This text began from a broad perspective that was very much in line with Kellner’s understanding of the power of cinema: Films can also provide allegorical representations that interpret, comment on, and indirectly portray aspects of an era. Further there is an aesthetic, philosophical, and anticipatory dimension to flm, in which they provide artistic visions of the world that might transcend the social context of the moment and articulate future possibilities, positive and negative, and pro- vide insight into the nature of human beings, social relationships, institu- tions, and conficts of a given era. (14) From this point of view, this book considered the movies that it ana- lyzed within the technological and military “eras” they were made and frst viewed within, and considered the ways in which the war flm most often undermined the potential cooperative power of Internet-enabled machine species with a continued focus on the humanistic ethics laid out by Jeffords’ Reagan-era hard body. The “insight” the movies provided reifed the fears and concerns found in the moviemaking machinic phy- lum of Hollywood and its overlap with the American State War Machine, all the while deconstructing the documents as windows into “the nature of human beings, social relationships, institutions, and conficts” as it related to the civilian machinic audience of war flms. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 229 A. Tucker, Virtual Weaponry, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-60198-4 230 CONCLUSION: What MIGHT A WAR FILM LOOK LIKE GOING FOrwarD? This book is being published with the knowledge that, like Interfacing with the Internet in Popular Cinema, it is far from compre- hensive and with the hope that other scholars might pick up some of the initial or underdeveloped thoughts that were begun with this text. -

Xm - Xxxyg - Xxx Hot Video Desi Sex Sex Video Sexy Video

xm - xxxyg - Xxx Hot video Desi Sex Sex Video Sexy Video Triple X syndrome - Wikipedia Directed by D.J. Caruso. With Vin Diesel, Donnie Yen, Deepika Padukone, Kris Wu. Xander Cage is left for dead after an incident, though he secretly returns to action for a new, tough assignment with his handler Augustus Gibbons. XXX (2002 film) - Wikipedia Triple X syndrome, also known as trisomy X and 47,XXX, is characterized by the presence of an extra X chromosome in each cell of a female. Those affected are often taller than average. xXx: Return of Xander Cage (2017) - IMDb Triple X syndrome, also known as trisomy X and 47,XXX, is characterized by the presence of an extra X chromosome in each cell of a female. Those affected are often taller than average. XXX (2002 film) - Wikipedia Directed by D.J. Caruso. With Vin Diesel, Donnie Yen, Deepika Padukone, Kris Wu. Xander Cage is left for dead after an incident, though he secretly returns to action for a new, tough assignment with his handler Augustus Gibbons. xXx (2002) - IMDb xXx (pronounced as Triple X) is a 2002 American spy thriller action film directed by Rob Cohen, produced by Neal H. Moritz and written by Rich Wilkes.The first installment in the xXx franchise, the film stars Vin Diesel as Xander Cage, a thrill-seeking extreme sports enthusiast, stuntman and rebellious athlete-turned reluctant spy for the ... XXX (@ShelcoGarcia) Twitter Directed by D.J. Caruso. With Vin Diesel, Donnie Yen, Deepika Padukone, Kris Wu. Xander Cage is left for dead after an incident, though he secretly returns to action for a new, tough assignment with his handler Augustus Gibbons. -

Research Paper Teguh Setiawan A320060121 School

TORETTO’S STREET GANG AMBITION REFLECTED IN THE FAST AND THE FURIOUS MOVIE (2001) DIRECTED BY ROB COHEN: A PSYCHOANALYTIC APPROACH. RESEARCH PAPER Submitted As Partial Fulfillment of Requirement for Getting Bachelor Degree of Education in English Department By TEGUH SETIAWAN A320060121 SCHOOL OF TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF SURAKARTA 2010 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Study The Fast and the Furious movie (2001) is directed by Robert Cohen. This film was produced by Neal H. Moritz. The genres of this film are action, crime, and thriller. The Fast and the Furious movie were first published on 22 June 2001 in USA. The next release in United Kingdom at September 14, 2001 and in Australia September 20, 2001. This film conveys about the Asian automotive import and takes setting in North America. The situation and condition of this film was inspired by Vibe and Ken Li magazine’s article that talked about street racing (Racer X), written by Gary Scott Thompson, Erik Bergquist, and David Ayer in New York City. This film has biggest stars such like; Paul Walker as Brian Earl Spilner or Brian O’Connor, Van Diesel as Dominic Toretto, Michelle Rodriguez as Letty, Jordana Brewster as Mia Toretto, Rick Yune as Johnny Tran, Chad Lindberg as Jesse, Johnny Strong as Leon, Matt Schulze as Vince, Ted Levine as Sgt. Tanner, Ja Rule as Edwin, Vyto Ruginis as Harry, Noel Gugliemi as Hector, R.J. de Vera as Danny Yamato, Stanton Rutledge as Muse, Thom Barry as Agent Bilkins. The Fast and the Furious movie was distributed by Universal Pictures USA. -

F9 Production Information 1

1 F9 PRODUCTION INFORMATION UNIVERSAL PICTURES PRESENTS AN ORIGINAL FILM/ONE RACE FILMS/PERFECT STORM PRODUCTION IN ASSOCIATION WITH ROTH/KIRSCHENBAUM FILMS A JUSTIN LIN FILM VIN DIESEL MICHELLE RODRIGUEZ TYRESE GIBSON CHRIS ‘LUDACRIS’ BRIDGES JOHN CENA NATHALIE EMMANUEL JORDANA BREWSTER SUNG KANG WITH HELEN MIRREN WITH KURT RUSSELL AND CHARLIZE THERON BASED ON CHARACTERS CREATED BY GARY SCOTT THOMPSON PRODUCED BY NEAL H. MORITZ, p.g.a. VIN DIESEL, p.g.a. JUSTIN LIN, p.g.a. JEFFREY KIRSCHENBAUM, p.g.a. JOE ROTH CLAYTON TOWNSEND, p.g.a. SAMANTHA VINCENT STORY BY JUSTIN LIN & ALFREDO BOTELLO AND DANIEL CASEY SCREENPLAY BY DANIEL CASEY & JUSTIN LIN DIRECTED BY JUSTIN LIN 2 F9 PRODUCTION INFORMATION PRODUCTION INFORMATION TABLE OF CONTENTS THE SYNOPSIS ................................................................................................... 3 THE BACKSTORY .............................................................................................. 4 THE CHARACTERS ............................................................................................ 7 Dom Toretto – Vin Diesel ............................................................................................................. 8 Letty – Michelle Rodriguez ........................................................................................................... 8 Roman – Tyrese Gibson ............................................................................................................. 10 Tej – Chris “Ludacris” Bridges ................................................................................................... -

Zakk V. Diesel (2019) 33 Cal.App.5Th 431 an Amended Complaint Consistent with a Previous Complaint's Allegations of a Specific

Zakk v. Diesel (2019) 33 Cal.App.5th 431 An amended complaint consistent with a previous complaint’s allegations of a specific contract, but omitting allegations of an overarching contract, was not a sham pleading. FACTS/PROCEDURE George Zakk was the executive producer for several films by One Race Films, Inc, which is owned by Vin Diesel. In March 2016, Zakk brought suit against Diesel, One Race Films, Inc., and Revolution Studios for breach of an oral contract, breach of an implied-in-fact contract, intentional interference with contractual relations, quantum meruit, promissory estoppel, and declaratory relief. Zakk alleged that he had an oral/implied-in-fact contract with Defendants under which Zakk would act as Executive Producer for various One Race films and receive compensation for each film ranging from $250,000 to $275,00. The alleged contract also stated that Zakk would receive an Executive Producer credit and identical compensation for any sequels produced, regardless of Zakk’s involvement in those sequels. Specifically, Zakk claimed in his suit that he was entitled to an Executive Producer credit and compensation for the xXx sequels (xXx was a 2002 film which Zakk worked on and developed for Defendants). During the pleadings stage, Zakk filed three amended complaints, and Defendants responded each time with demurrers. In the final demurrer, Defendants alleged that Zakk’s third amended complaint was a sham pleading for two reasons: (1) in the third amended complaint, Zakk alleged the existence of multiple contracts (one for each film), while previously, Zakk alleged the existence of only a single contract (applicable to all films); and (2) in the third amended complaint, Zakk adjusted the range of compensation he alleged he was entitled to receive from the previous complaints. -

Borrero, C.A.S

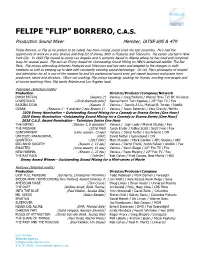

FELIPE “FLIP” BORRERO, C.A.S. Production Sound Mixer Member, IATSE 695 & 479 Felipe Borrero, or Flip as he prefers to be called, has been mixing sound since the late seventies. He’s had the opportunity to work on a very diverse and long list of shows, both in Features and Television. His career started in New York City. In 1993 Flip moved to sunny Los Angeles and is currently based in Atlanta where he has lived and remained busy for several years. Flip won an Emmy Award for Outstanding Sound Mixing on HBO’s acclaimed telefilm The Rat Pack. Flip enjoys alternating between Features and Television and has seen and adapted to the changes in both mediums as well as keeping up to date with constantly evolving sound technology. On set, Flip’s philosophy of respect and admiration for all is one of the reasons he and his professional sound crew get repeat business and praise from producers, talent and directors. When not working, Flip enjoys kayaking, cooking for friends, meeting new people and of course watching films. Flip works Atlanta and Los Angeles local. Television (Selected credits) Production Director/Producer/Company/Network DOOM PATROL (Season 2) Various / Greg Berlanti / Warner Bros TV/ DC Universe LOVESTRUCK (2019 dramedy pilot) Sanna Hamri Tom Kapinos / 20th Fox TV / Fox RAISING DION (Season 1) Various / Dennis A Liu, Michael B. Jordan / Netflix OZARK (Seasons 2 - 4 and last 2 eps Season 1) Various / Jason Bateman / Zero Gravity /Netflix 2020 Emmy Nomination – Outstanding Sound Mixing for a Comedy or Drama Series (One Hour) 2019 Emmy Nomination –Outstanding Sound Mixing for a Comedy or Drama Series (One Hour) 2018 C.A.S. -

JONATHAN LUCAS Editor

JONATHAN LUCAS Editor Television PROJECT DIRECTOR STUDIO / PRODUCTION CO. THE TROUBLE WITH MAGGIE COLE (series) Various ITV / Genial Productions Cast: Dawn French, Mark Heap Prod: Mark Brotherhood, Sophie Clarke-Jervoise YEARS AND YEARS (miniseries) Lisa Mulcahy BBC / Canal+ / HBO Cast: Emma Thompson Prod: Russell T. Davies RANDOM ACTS (series) Annie Griffin Channel 4 / Little Dot Studios Prod: Fiona Lamptey THE MOONSTONE (mini-series) Lisa Mulcahy BBC / King Bert Cast: Joshua Silver, John Calder, Terenia Edwards Prod: Joanna Hanley Feature Films PROJECT DIRECTOR STUDIO / PRODUCTION CO. UNDERCLIFFE Lisa Mulcahy Open Palm Films Cast: Laurie Kynaston, Mark Addy, Akbar Kurtha Prod: Dominic Dromgoole World Premiere: 2018 Austin Film Festival THE FLIGHT FANTASTIC (documentary) Tom Moore Damiki Productions Cast: Tito, Armando, Chela and Richie Gaona HIDE AWAY Chris Eyre MMC Joule Films Cast: Josh Lucas, James Cromwell, Ayele Zurer Prod: Sally Jo Effenson, Carl Effenson DIRTY GIRL Abe Sylvia Killer Films / The Weinstein Company Cast: Juno Temple, Jeremy Dozier, Zach Lasry Prod: Rob Paris, Christine Vachon AMERICAN COWSLIP Mark David Buffalo Speedway / Entertainment One Cast: Diane Ladd, Rip Torn, Cloris Leachman Prod: Steve Blevins, Tony Hewett A PLUMM SUMMER Caroline Zelder Fairplay Pictures Cast: Jeff Daniels, Henry Winkler, Lisa Guerrero Prod: Frank Antonelli CORPSE BRIDE Tim Burton Warner Bros. Cast: Johnny Depp, Helena Bonham Carter Mike Johnson Prod: Allison Abate, Jeffrey Auerbach THE POSTMAN*** Kevin Costner Warner Bros. / Tig Productions Cast: Kevin Costner, Will Patton, Larenz Tate Prod: Steve Tisch, Jim Wilson Editor: Peter Boyle WATERWORLD*** Kevin Reynolds Universal Pictures Cast: Kevin Costner, Rick Aviles, R.D. Call Prod: John Davis, Lawrence Gordon Editor: Peter Boyle TROY** Wolfgang Petersen Warner Bros.