Ringtones, Or the Auditory Logic of Globalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Importance of Being Digital Paul Lansky 3/19/04 Tart-Lecture 2004

The Importance of Being Digital Paul Lansky 3/19/04 tART-lecture 2004 commissioneed by the tART Foundation in Enschede and the Gaudeamus Foundation in Amsterdam Over the past twenty years or so the representation, storage and processing of sound has moved from analog to digital formats. About ten years audio and computing technologies converged. It is my contention that this represents a significant event in the history of music. I begin with some anecdotes. My relation to the digital processing and music begins in the early 1970’s when I started working intensively on computer synthesis using Princeton University’s IBM 360/91 mainframe. I had never been interested in working with analog synthesizers or creating tape music in a studio. The attraction of the computer lay in the apparently unlimited control it offered. No longer were we subject to the dangers of razor blades when splicing tape or to drifting pots on analog synthesizers. It seemed simple: any sound we could describe, we could create. Those of us at Princeton who were caught up in serialism, moreover, were particularly interested in precise control over pitch and rhythm. We could now realize configurations that were easy to hear but difficult and perhaps even impossible to perform by normal human means. But, the process of bringing our digital sound into the real world was laborious and sloppy. First, we communicated with the Big Blue Machine, as we sometimes called it, via punch cards: certainly not a very effective interface. Next, we had a small lab in the Engineering Quadrangle that we used for digital- analog and analog-digital conversion. -

Biography: Jocelyn Pook

Biography: Jocelyn Pook Jocelyn Pook is one of the UK’s most versatile composers, having written extensively for stage, screen, opera house and concert hall. She has established an international reputation as a highly original composer winning her numerous awards and nominations including a Golden Globe, an Olivier and two British Composer Awards. Often remembered for her film score to Eyes Wide Shut, which won her a Chicago Film Award and a Golden Globe nomination, Pook has worked with some of the world’s leading directors, musicians, artists and arts institutions – including Stanley Kubrick, Martin Scorsese, the Royal Opera House, BBC Proms, Andrew Motion, Peter Gabriel, Massive Attack and Laurie Anderson. Pook has also written film score to Michael Radford’s The Merchant of Venice with Al Pacino, which featured the voice of countertenor Andreas Scholl and was nominated for a Classical Brit Award. Other notable film scores include Brick Lane directed by Sarah Gavron and a piece for the soundtrack to Gangs of New York directed by Martin Scorsese. With a blossoming reputation as a composer of electro-acoustic works and music for the concert platform, Pook continues to celebrate the diversity of the human voice. Her first opera Ingerland was commissioned and produced by ROH2 for the Royal Opera House’s Linbury Studio in June 2010. The BBC Proms and The King’s Singers commissioned to collaborate with the Poet Laureate Andrew Motion on a work entitled Mobile. Portraits in Absentia was commissioned by BBC Radio 3 and is a collage of sound, voice, music and words woven from the messages left on her answerphone. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

Public Voices

Public Voices Government at the Margins: Locating/Deconstructing Ways of Performing Government in the Age of Excessive Force, Hyper-Surveillance, Civil Dis- obedience, and Political Self-interest – Lessons Learned in “Post-Racial” America Symposium Symposium Editor Valerie L. Patterson School of International and Public Affairs Florida International University Editor-in-Chief Marc Holzer Institute for Public Service Suffolk University Managing Editor Iryna Illiash Volume XV Number 2 Public Voices Vol. XV No. 2 Publisher Public Voices is published by the Institute for Public Service, Suffolk University. Copyright © 2018 Subscriptions Subscriptions are available on a per volume basis (two issues) at the following rates: $36 per year for institutions, agencies and libraries; $24 per year for individuals; $12 for single copies and back orders. Noninstitutional subscribers can make payments by personal check or money order to: Public Voices Suffolk University Institute for Public Service 120 Tremont Street Boston, MA 02108 Attn: Dr. Marc Holzer All members of SHARE receive an annual subscription to Public Voices. Members of ASPA may add SHARE membership on their annual renewal form, or may send the $20 annual dues at any time to: ASPA C/o SunTrust Bank Department 41 Washington, DC 20042-0041 Public Voices (Online) ISSN 2573-1440 Public Voices (Print) ISSN 1072-5660 Public Voices Vol. XIV No. 2 Public Voices Editor-in-Chief: Marc Holzer, Suffolk University, Institute for Public Service Managing Editor: Iryna Illiash, CCC Creative Center Editorial Assistant: Jonathan Wexler, Rutgers University - Campus at Newark Editorial Assistant: Mallory Sullivan, Suffolk University, Institute for Public Service Editorial Board Robert Agranoff, Indiana University Robert A. -

Texas Bowling Scores Team Houston Meeting

NEXT THURS'DAY.DECEMBER 14 * diJIect ~/(OWI ~ag CVegag HOT CHOCOLATE _~.b. ~1 ~ ~ - hmne bOlt the hoQtdayg - .Jgf3)- ~ $: _11 1 .,.* ~ FREE:WE:LL 10PM-11 PM ~ FREE BEER 9 PM-TILL EJ1&tc p.. CI tlt/letC/ftJ6' ",1 (51Q) 474-9667 WEDNESDflY) THUR)DflY) FRIDflY') )flTURDflY) )UNDflY) )HOW Probe AU)TIN') ~1 LONGNEC~) NICOLE NIGHT WITH DJ ORIGINAL UNTIL HOm 11PM MICHAEL 104 DRIN~ MIDNIGHT MU)(LE) HERNANDEZ NIGHT IN ACTION AT 11 PM FREE BEER ~150 WELL & FREE BEER AFTERHOUR) WOWELL -COMING DECEMBER QO- THE B04THOU)E TtKIN CHRIS"TMflSPfiRTY" AND FRACTUREDCHRIS"TMASS"HOW" AN EVENING AT TEXAS· STYLE Direct from La Cage at The Riviera Hotel/Las Vegas HOT CHOCOLATE SHOW TIME IlPM Direct from La Cage at Bally's in Atlantic City lKE "CHAMPAGNE" SUTTON plus Texas' Top Impersonators 19 NEWS World AIDSDay in Dallas and Houston 34 SPECIAL REPORT Judge Hampton Harshly Reprimanded 39 COMMENT Letters to the Editor 45 VIEWPOINT Gays Mistreated in Texas Prisons by Ansul Cole 51 SPORTS Team Houston Organizational Meeting by Bobby Millef 52 BACKSTAGE Sister'sChristmas Wish List by Marc Alexander NAOMI SIMS 55 CLASSIC TWT 4 Years Ago ThisWeek in Texas by Bob Dineen 59 HOT TEA Texans Gear Up for the Holidays with Parties and Shows The stars come out in an evening of illusion! 67 STARSCOPE December 12FullMoon by Milton yon Stern 70 COVER FEATURE Austin's Mollie lIey photos by Susan Yeatman 75 CALENDAR Special One-Time Only and Nonprofit Community Events ONE NIGHT ONLY 76 CLASSIFIED Wont Ads and Notices 84 GUIDE Texas BusinessI Club Directory TWT (This Week in Texas) is pubUshedby1"exas Weekly Times Newspaper Co, at 3900 Lemmon Ave, in Dallas, Texas TUESDAY , 75219and 811Westhe:lmer in Houston. -

Howard Skempton

Jocelyn Pook Anxiety Fanfare and Variations for Voices First commissioned by the Mental Health Foundation for Anxiety Arts Festival London 2014 and premiered at the Wigmore Hall, London this work extends the multi-award winning composer Jocelyn Pook’s interest in the experience of mental illness, which she explored in her ground-breaking 2012 work Hearing Voices. Written in five movements, the Anxiety Fanfare is performed by the Jocelyn Pook Ensemble and the community singers of the London International Gospel Choir, led by Naveen Arles. The soloists are soprano Loré Lixenberg, mezzo-soprano Melanie Pappenheim, countertenor Jonathan Peter Kenny and bass George Ikediashi. Artists: Jocelyn Pook Ensemble | London International Gospel Choir Timing: 23’49 Jocelyn Pook Ensemble: Elle Sillanpaa Jocelyn Pook composer/viola Emilie Schultze Jonathan Peter Kenny conductor/countertenor Eszter Lakatos Melanie Pappenheim mezzo-soprano Georgina Hole Lore Lixenberg soprano Shirley Davies George Ikediashi bass Zsuzsanna Incze Luiz De Campos tenor Jessica Fair Emma Smith violin Lauren Davis Preetha Narayanan violin Essi Turkson Richard Jones viola Laura Pertuy Sophie Harris cello Vivien Sproule Midori Jaeger cello Yoko Koshiyama Megan Roberts trombone Peter Coleman Rory Cartmell trombone Claudina Spooner Christian Barraclough trumpet Cyril Dorsett Shane Brennan trumpet Julija Surovecaite Marco Nikic The London International Gospel Choir: Michaela Janks Naveen Arles leader Alex Wilson Lisa Burmeister Dominic Šimkus About Jocelyn Pook Jocelyn Pook is one of the UK’s most versatile composers, having written extensively for stage, screen, opera house and concert hall. She has established an international reputation as a highly original composer winning her numerous awards and nominations including a Golden Globe, an Olivier and two British Composer Awards. -

E M M a H O L L a N D

E M M A H O L L A N D P R SACHA WARES RETURNS TO THE ALMEIDA THEATRE FOLLOWING LAST YEAR’S CRITICALLY ACCLAIMED PRODUCTION OF MIKE BARTLETT’S GAME TO DIRECT THE WORLD PREMIERE OF BOY A NEW PLAY BY LEO BUTLER FROM 5 APRIL – 28 MAY 2016 AND A COMPLEMENTARY OUTREACH PROGRAMME FUNDED BY THE ARSENAL FOUNDATION SEES THE ALMEIDA PARTNER WITH ARSENAL IN THE COMMUNITY TO FURTHER ENGAGE WITH THE YOUNG PEOPLE OF THE LONDON BOROUGH OF ISLINGTON Sacha Wares will be returning to Almeida Theatre to direct the world premiere of Leo Butler’s new play Boy, after her directorial success with the critically acclaimed production, Game, by Mike Bartlett, in 2015. Boy will run at the Almeida Theatre from 5 April until 28 May 2016, with press night on 12 April 2016. Director Sacha Wares is joined by a formidable creative team, including two powerhouse contemporary designers, Miriam Buether for set design (Wild Swans, Sucker Punch, My Child, Generations), who worked with Sacha on Game at the Almeida in 2015, and Ultz for costume (Jerusalem, Hobson’s Choice, Fallout, Pied Pier), who will be collaborating with Miriam, on design, for the very first time. Further creative credits include movement by Leon Baugh, lighting by Jack Knowles and sound by Gareth Fry. A boy At a bus stop. Easily missed. Playwright Leo Butler casts a sharp eye over the city and picks someone for us to follow. Sacha Wares (Director) is associate director at the Young Vic and was previously Associate Director of the Royal Court from 2007-2013. -

DJ Andy Stott Udforsker Stilhed Og Støj Med Smukke Lydbilleder I VEGA

2016-09-09 11:00 CEST DJ Andy Stott udforsker stilhed og støj med smukke lydbilleder i VEGA VEGA præsenterer DJ Andy Stott udforsker stilhed og støj med smukke lydbilleder i VEGA Torsdag den 8. december indtager den anmelderroste og nyskabende Andy Stott Lille VEGA og bringer drømme- og trancelignende tilstande til sit publikum med smukke lydbilleder. Den Manchester-baserede producer, Andy Stott, nægter at lade sit elektroniske talent begrænse af pre-definerede genrer. Han bevæger sig fra alt imellem dyb techno, garage, stille house, footwork, grime og bølgende pop-mutationer. Der er dog konstanter i hans musik i form af Stotts unikke vekslen mellem dystre og drømmende teksturer, hans legen med rytmen i sangene samt en luftig og sårbar vokal, som alt sammen skaber en dybde og kompleksitet i et betagende smukt musikunivers. Intensitet og intelligens i beundringsværdig kompromisløshed Senest har Stott udgivet albummet Too Many Voices i foråret 2016, vis titel kan ses som en frisk reference til hans diversitet og konstante udvikling inden for musikken. Hans gamle klaverlærer, Alison Skidmore, bidrager med sin yderst delikate vokal på flere af produktionerne. Too Many Voices er et album, der med ekstrem intelligens og udefinerede rytmer vækker både melankolske og drømmende følelser hos lytteren. Lyt selv med på nummeret ”Butterflies” fra albummet. Stott fik for alvor hul igennem med Luxury Problems i 2012, et melodisk techno- og housealbum. Det efterfølgende album, der blev udnævnt til album of the year i2014 af Resident Advisor, udkom i slutningen af 2014 med titlen Faith In Strangers. Soundvenue skrev dengang om albummet: ”Man står tilbage med fornemmelsen af albummet som et lille melodisk paradoks, der udforsker forholdet mellem en flydende overjordisk stilhed og en industriel jordisk støj, og det er ganske interessant.” Fakta om koncerten: Andy Stott (UK) Torsdag den 8. -

Sadler's Wells Spring / Summer 2017

Spring / Summer 2017 1 Contents 01 A message from Alistair Spalding 02 Associate Artists and Companies 03 Artists' development 04 Sadler’s Wells Theatre 14 Supporting Young Artists 25 Enjoy More of Sadler’s Wells 26 Calendar 29 How to Book 30 Planning Your Journey 36 Lilian Baylis Studio 42 London International Mime Festival 44 The Peacock 48 Family Shows 51 Sadler's Wells on Tour 52 Talks, Classes and Assisted Performances 54 Patrons' Events 55 Join us Save 20% when you book Family Friendly two or more shows at the Performances and activities same time Available on all with this symbol are suitable shows displaying this symbol. for most ages. Age guidance Discount is automatically is given for some shows added in your online basket. where relevant. This offer is available until 31 January 2017. Assisted performances: Terms and conditions apply: Look for these symbols, sadlerswells.com/save or visit sadlerswells.com/ assistedshows New ways to save from 1 February 2017 Our ‘Save BSL Interpreted 20%’ scheme is changing, with new discounts, and new ways of obtaining the discount. Audio Described For details: AD sadlerswells.com/save Transaction charges apply This brochure is available £3 for telephone bookings, in a large print version. £1.95 for concessionary and online bookings. No charge when booking in person. 2 A message from Alistair Spalding Welcome to our Spring/Summer 2017 In March, we are presenting Tree season. I often say that, at Sadler’s of Codes, another Sadler’s Wells Wells, our commitment is to the artist co-production. Choreographed by rather than the work. -

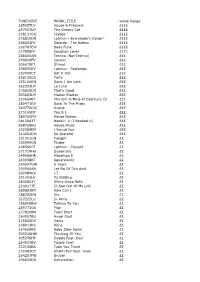

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 285057LV

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 285057LV House & Pressure ££££ 297057LM The Groovy Cat ££££ 298131GQ Jaydee ££££ 276810DN Latmun - Everybody's Dancin' ££££ 268301FV Solardo - The Aztecs ££££ 292787EW Body Funk ££££ 277998FP Egyptian Lover ££££ 286605AN Techno (Not Techno) £££ 276810FV Cosmic £££ 306678FT Strand £££ 296595EV Latmun - Footsteps £££ 252459CT Set It Out £££ 292130GU Party £££ 255100KN Sorry I Am Late £££ 262293LN La Luna £££ 276810DQ That's Good £££ 303663LM Master Blaster £££ 220664BT The Girl Is Mine Ft Destiny's Ch £££ 280471KV Back To The Music £££ 323770CW Sueno £££ 273165DT You & I £££ 289765FN House Nation £££ 0412043T Needin' U (I Needed U) £££ 268756KU House Music £££ 292389EM I Found You £££ 314202DM So Grateful £££ 131751GN Tonight ££ 130999GN Finder ££ 296595CT Latmun - Piquant ££ 271719HU Saxomatic ££ 249988HR Moorthon Ii ££ 263938BT Aguardiente ££ 250247GW 9 Years ££ 294966AN Let Go Of This Acid ££ 292489KV 17 ££ 291041LV Ya Kidding ££ 3635852T Shiny Disco Balls ££ 2240177E In And Out Of My Life ££ 269881EM How Can I ££ 188782KN Xtc ££ 327225LU In Arms ££ 156808BW Talking To You ££ 289773GU Play ££ 277820BN False Start ££ 264557BU Angel Dust ££ 215602DR Veins ££ 238913KS Nana ££ 224609BS Baby Slow Down ££ 300216HW Thinking Of You ££ 305278HT Desole Feat. Davi ££ 264557BV Twiple Fwet ££ 232106BS Take You There ££ 272083CP Shakti Pan Feat. Sven ££ 254207FW Bruzer ££ 296650DR Satisfaction ££ 261261AU Burning ££ 2302584E Atlantis ££ 036282DT Don't Stop ££ 309979LN The Tribute ££ 215879HU Devil In Me ££ 290470BR Kubrick -

The Measure of Me

LASALLE College of the Arts presents The Measure of Me CHOREOGRAPHERS Dapheny Chen Yarra Ileto Kuik Swee Boon Melissa Quek FROM THE DEAN STAGE The LASALLE Show season is an extended opportunity for the Faculty of Performing Arts to present the remarkable talents of students graduating from our programmes in the School of Contemporary Music and the School of Dance and Theatre. The COVID-19 pandemic has had an impact on all our work. While we had to work ingeniously with digital technology to record student work and severely limit the audience access to performances, the accomplishments of our graduates are nothing short of extraordinary. Conservatory-level training, of the kind we offer at LASALLE College of the Arts, prepares graduates for all that a high-performance career demands in the different areas of the creative and entertainment industries. At a stage where these industries are growing parts of the economy in Singapore, we are proud that we are equipping students with the necessary technical skills and inspired creativity to help them establish and manage the long careers that lie ahead. New realities following COVID-19 mean that new skills will be employed. So our musicians, composers, actors, musical theatre performers, dancers and technicians leave LASALLE having grown their individual talents and refined their transferable skills to confront the next normal. Throughout April, we are showcasing productions by our programmes in BA(Hons) Acting (Vassa, Mike Bartlett’s adaptation of Maxim Gorky’s original black comedy written -

The Jocelyn Pook Ensemble and the Nottingham People's Choir Present

The Jocelyn Pook Ensemble and the Nottingham People’s Choir present Jocelyn Pook’s Anxiety Fanfare and Variations for Voices on 30 September at Nottingham Contemporary © Laurel Turton Wednesday 30 September Nottingham Contemporary | 7.30pm Anxiety Fanfare and Variations for Voices Music and words by Jocelyn Pook Donna Lennard soprano Melanie Pappenheim mezzo-soprano Jonathan Peter Kenny countertenor George Ikediashi bass Jocelyn Pook Ensemble Nottingham People’s Choir Jocelyn on BBC News talking about Anxiety Fanfare Following their performance at the Tête à Tête Opera Festival last week, the Jocelyn Pook Ensemble will join forces with the Nottingham People’s Choir to perform Pook’s Anxiety Fanfare and Variations at Nottingham Contemporary on September 30. The choir is funded by the Institute of Mental Health - a partnership between Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Nottingham. They will be performing alongside soloists Donna Lennard (soprano), Melanie Pappenheim (mezzo-soprano), Jonathan Peter Kenny (countertenor) and George Ikediashi (baritone). “It’s very positive to talk about mental health issues which are still stigmatised in society and yet they are so common.” Jocelyn Pook Commissioned by the Mental Health Foundation and premièred at the Wigmore Hall as part of the Anxiety Arts Festival London 2014, the Anxiety Fanfare and Variations is a musical exploration of everyday mental health disorders written in five movements. The theme of mental health is very personal to Pook, whose family has been touched by mental illness over three generations. The Mental Health Foundation commissioned critically-acclaimed Jocelyn Pook to write the Anxiety Fanfare after her song-cycle Hearing Voices in 2012, also on the topic of mental health.