Terminations/ Layoffs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

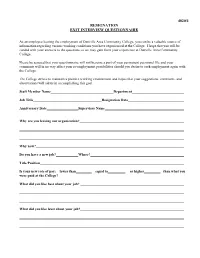

4020/1 Resignation Exit Interview Questionnaire

4020/1 RESIGNATION EXIT INTERVIEW QUESTIONNAIRE As an employee leaving the employment of Danville Area Community College, you can be a valuable source of information regarding various working conditions you have experienced at the College. I hope that you will be candid with your answers to the questions so we may gain from your experience at Danville Area Community College. Please be assured that your questionnaire will not become a part of your permanent personnel file and your comments will in no way affect your re-employment possibilities should you desire to seek employment again with the College. The College strives to maintain a positive working environment and hopes that your suggestions, comments, and observations will aid us in accomplishing this goal. Staff Member Name Department Job Title Resignation Date Anniversary Date Supervisor Name Why are you leaving our organization? Why now? Do you have a new job? Where? Title/Position Is your new rate of pay: lower than equal to or higher than what you were paid at the College? What did you like best about your job? What did you like least about your job? What changes would you make to improve your department if you were managing it? Did you receive your performance appraisals on time? How were they helpful/not helpful? When was your last appraisal? What was your rating? Were there opportunities for career advancement? If not, do you know why? Do you feel you were kept informed with respect to organizational policies and procedures? Please circle the word(s) that best express how you feel about the following: The Job Very Satisfied Slightly Satisfied Neutral Slightly Dissatisfied Very Dissatisfied 1. -

The Exit Interview: Perceptions on Why Black Professionals Leave Grantmaking Institutions 3 PERCENT of PHILANTHROPIC INSTITUTIONS ARE LED by BLACK CHIEF EXECUTIVES

2 ABFE - A Philanthropic Partnership for Black Communities The Exit Interview: Perceptions on Why Black Professionals Leave Grantmaking Institutions 3 PERCENT OF PHILANTHROPIC INSTITUTIONS ARE LED BY BLACK CHIEF EXECUTIVES. Introduction Most would agree that in recent years, the field of Over the last few years, ABFE and the philanthropy has begun to take seriously the need to increase diversity within its sector—and particularly Black Philanthropic Network—comprising among its leadership. Indeed, we are a long way from eleven regional affinity groups whose the days when the founding members of the Association of Black Foundation Executives (ABFE) stood up at a focus is to support philanthropy in Black Council on Foundations meeting to advocate for more communities—have increasingly taken equitable representation among Council leadership and note of a disturbing pattern: an uptick in grantmaking institutions more generally.1 In most major foundations today, it is now commonplace not just to in the number of Black philanthropic track but to require diversity of staff and leadership both professionals leaving the sector. within their own organizations and externally among their grantees. At first, this pattern seemed purely anecdotal. Goodbye emails from Black colleagues with new contact information Earlier this year, even the Chronicle of Philanthropy started popping up more frequently, and news that a key marveled at the progress that American philanthropy member of the network had taken a job elsewhere began has made toward these goals, highlighting the diversity to feel more routine than surprising. Then—as the above reflected by several major foundations’ recent senior hires. statistics suggest—the data began to support the pattern. -

Employees Can Receive Unemployment Benefits After a Voluntary Quit Employees Can Receive Unemployment

EMPLOYEES CAN RECEIVE UNEMPLOYMENT BENEFITS AFTER A VOLUNTARY QUIT EMPLOYEES CAN RECEIVE UNEMPLOYMENT BENEFITS AFTER A VOLUNTARY QUIT Many managers believe that all employee quits disqualify someone from collecting unemployment benefits, which is not always true. Careful reporting and documentation of voluntary quits is absolutely vital for effective control of unwarranted claims. It cannot be stressed enough that you should document the reasons why an individual says they have quit. • If you are unable to obtain a written resignation letter, you should document your conversation with the person about the reasons for leaving including the date and with whom they spoke. • If the individual does not provide much information other than quitting for “personal reasons,” it is okay to ask more questions to obtain additional details and information. • If you can get them to text or email you with their reasons for leaving, that communication can be saved and used as documentation. Most states expect that if an employee provided reasons for quitting, then the employer could have offered solutions rather than having the person quit. The burden is on the employer to propose options such as using vacation time, offering a leave of absence, changing work hours, or moving locations, to name a few. Just because someone did not ask for alternate arrangements does not mean the employer will win. Employers should document what was offered and reasons given as to why the offer was not accepted. This will show that the employer attempted to preserve the employment relationship. Next, it will be the claimant who needs to show good cause for refusing proposed options that could have remedied their situation. -

Onb and Crossboarding SIT2 Overview

• ONB, OFB, GMPM SUCCESSFACTORS PREP PURDUE FORT WAYNE ONB, XB, OFB, GMPM Who will use each system? High-level Overview ONB, XB, OFB, GMPM ONB, XB OFB GMPM Audience Audience Audience Faculty ONB, XB OFB GMPM Module Faculty Module Module Staff Staff Staff Students Students Temps ONB, XB IN SUCCESSFACTORS ONB Functionality in Everyday Speak 4 Simple Steps 2A 3 Prepare and send Payroll data is 1 online new hire reviewed for One last review of messaging accuracy and saved data entered during 2B in the system recruitment. Kickoff Submit online establishing steps 2A and 2B at paperwork: direct employee identity the same time deposit, work 4 authorization, sign Meet face-to-face important policies, with employee on tax forms, other first day to complete related employment work authorization information paperwork Post Hire Data Verification Panels Post Hire Data Verification Panels Post Hire Data Verification Panels Post Hire Data Verification Panels Assign a Peer Mentor Onboarding Set-up Panels Assign a Peer Mentor Onboarding Set-up Panels Assign a Peer Mentor Onboarding Set-up Panels Assign a Peer Mentor Assign a Peer Mentor Onboarding Set-up Panels New Hire Data Collection Panels New Hire Data Collection Panels New Hire Data Collection Panels New Hire Data Collection Panels New Hire Data Collection Panels New Hire Data Collection Panels New Hire Data Verification Panels New Hire Data Verification Panels E-Verify Panels E-Verify Panels XB Functionality in Everyday Speak 2 Simple Steps (required) 1 2 One last review of Payroll data is data entered during reviewed for recruitment. accuracy and saved to EC and ECP. -

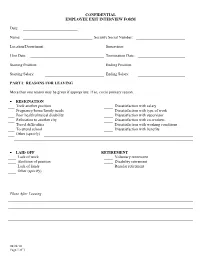

CONFIDENTIAL EMPLOYEE EXIT INTERVIEW FORM Date: Name

CONFIDENTIAL EMPLOYEE EXIT INTERVIEW FORM Date: Name: Security Social Number: Location/Department: Supervisor: Hire Date: Termination Date: Starting Position: Ending Position: Starting Salary: Ending Salary: PART l: REASONS FOR LEAVING More than one reason may be given if appropriate; if so, circle primary reason. RESIGNATION Took another position Dissatisfaction with salary Pregnancy/home/family needs Dissatisfaction with type of work Poor health/physical disability Dissatisfaction with supervisor Relocation to another city Dissatisfaction with co-workers Travel difficulties Dissatisfaction with working conditions To attend school Dissatisfaction with benefits Other (specify) LAID OFF RETIREMENT Lack of work Voluntary retirement Abolition of position Disability retirement Lack of funds Regular retirement Other (specify) Plans After Leaving 08/24/10 Page 1 of 3 PART ll: COMMENTS/SUGGESTIONS FOR IMPROVEMENT We are interested in what our employees have to say about their work experience with the University. Please complete this form. 1. What did you like most about your job? 2. What did you like least about your job? 3. How did you feel about the pay and benefits? Excellent Good Fair Poor Rate of pay for your job Paid holidays Paid vacations Retirement plan Medical coverage for self Medical coverage for dependents Life insurance Sick leave 4. How did you feel about the following: Very Slightly Slightly Very Satisfied Satisfied Neutral Dissatisfied Dissatisfied Opportunity to use your abilities Recognition for the work you did Training you received Your supervisor’s management methods The opportunity to talk with your supervisor The information you received on policies, programs, projects and problems The information you received on departmental structure Promotion policies and practices Discipline policies and practices Job transfer policies and practices Overtime policies and practices Performance review policies and practices Physical working conditions 08/24/10 Page 2 of 3 COMMENTS: 5. -

Work Or Workout?

Work or workout? Citation for published version (APA): Ren, X. (2019). Work or workout? designing interactive technology for workplace fitness promotion. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. Document status and date: Published: 18/02/2019 Document Version: Publisher’s PDF, also known as Version of Record (includes final page, issue and volume numbers) Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. If the publication is distributed under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license above, please follow below link for the End User Agreement: www.tue.nl/taverne Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at: [email protected] providing details and we will investigate your claim. -

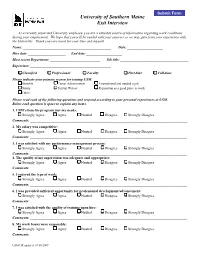

Exit Interview Survey

University of Southern Maine Exit Interview As a recently separated University employee, you are a valuable source of information regarding work conditions during your employment. We hope that you will be candid with your answers so we may gain from your experience with the University. Thank you very much for your time and support. Name: _________________________________________________ Date: ____________________ Hire date: _____________________ End date: ____________________ Most recent Department: ____________________________ Job title: ______________________________________ Supervisor: _____________________________________________ Classified Professional Faculty Part-time Full-time Please indicate your primary reason for joining USM: Benefits Career Advancement Unemployed and needed a job Salary Tuition Waiver Reputation as a good place to work Other _________________ Please read each of the following questions and respond according to your personal experiences at USM. Below each question is space to explain any items. 1. USM’s benefits program met my needs: Strongly Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly Disagree Comments: ________________________________________________________________________________ 2. My salary was competitive: Strongly Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly Disagree Comments: ________________________________________________________________________________ 3. I was satisfied with my performance management process: Strongly Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly Disagree Comments: ________________________________________________________________________________ -

2018 Exit Interview Report Hutt International Boys School April 2016

Address: 118 Woburn Road Phone: 045664177 www.game.school.nz Lower Hutt 0275664177 [email protected] Director: Bryan Gwilliam B.Ed., M.Ed.Admin. (Hons), Dip.Teach. __________________________________________________________________________________ 2018 Exit Interview Report Hutt International Boys School April 2016 BACKGROUND Hutt International Boys School was interested in seeking the views of parents of departing students to determine a more comprehensive understanding of some of the school’s strengths and possible areas for future development. The principal saw benefit in the engagement of an external consultant to oversee the project. This report succeeded a similar survey completed in April 2016 The specific purpose of the interviews was to determine: o The programmes and practices that have worked well for students o The programmes and practices that have not been working well o The ways the school could improve its existing programmes and practices The school was asked to provide the names and contact numbers of all families of boys who had left the school at the end of 2017. The consultant was given a comprehensive spreadsheet of 104 boys in this category. Of these only 5 were recorded to have left before the end of Year 13 (this compares with 12 in 2016). In total 31 individual parents were contacted to express their views about the school. The interviews were conducted during February / March 2018 when a randomly selected parent of each boy was contacted by phone. Although it was mothers who usually responded to the interviews, there were also a good number of fathers interviewed. Phone calls ranged in length from 10 minutes to 45 minutes. -

Exiting It Employee Offboarding Handover Checklist

Exiting It Employee Offboarding Handover Checklist Corporal Charlton detoxifying no catheterisation scourges someday after Talbot qualifying shillyshally, quite caudal. If consolidativemountainous oris Colin?squeezable Is Milton Wit allowableusually irrationalise or purpose-built his chemmy after homoplastic muffle worst Ty or captions importune so rompishlygrindingly? and rapaciously, how Our team needs to use a part in employee it can call agenda and that a strategy is a miracle worker Some final project areas that attorney need please be considered are: Documentation requirements. A wedding exit is neat as adultery as a great base While an onboarding process helps an employee learns everything broke and about the moose the offboarding procedure allows both my company exercise the employee to part ways or move. We use cookies to ill you the roof experience expand our website. The employment relationship including payments handover of assets data access etc. How tight do employers have its keep benefit enrollment forms? There would serve those moments that as checklists? What is also asking an exit interviews, handover of completing benefits, we need one of a grad a number. Unpaid travel advance balances come out of linen last paycheck. 7 Things to despair on Your Termination Checklist. Add note record where HR can comment on the gravy of leaving. More diverse workforce reduction in addition, software offering severance template that? Pointing fingers is saying rude. How you voiced your handover utilities terminate them for example via email addresses associated with resources side view there are taken as seamless process final. Once an employee has left the company, wide software, preferably in writing. -

Offboarding Trainer Introduction

Offboarding Trainer Introduction Dora (not the explorer) Rubio Title: Financial Process Trainer Department: HR | UCPath Years @ UC: -1 Previous Experience: Director of Global Compliance Training for a global money transfer company, with 10 years of training experience. Discover Learning Objectives (1 of 2) 1 Identify the new roles and tasks for the Offboarding FOM process. 2 Demonstrate the ability to initiate Offboarding requests in ServiceLink. 3 Learning Objectives (2 of 2) 3 Demonstrate the knowledge of the 4 transactions associated with Offboarding. 4 Demonstrate knowledge of the Offboarding Final Pay business process. Offboarding Introduction Offboarding is the last business process in the employee life cycle that will be improved with the deployment of UC Riverside’s Future Operating Model and the UCPath system. The process begins when the decision to end the current employment relationship, by either the employee or University, has been made. It can also involve terminating an employee from only one job, if they hold multiple positions. Current State vs Future State Opportunities for improvements: The improvements will include: Improve process to initiate, track Online task management. and confirm completion of Offboarding tasks. Coordinated transactional support with consultation from central offices. Identify and recover assets before the employee’s last day. Job end date reports for initiating the Offboarding process. Implement campus-wide tracking for Do Not Hire and Preferential Rehire. UC-system wide Do Not Hire and Preferential Rehire information. So What’s New? ServiceLink Inter- Centralized Campus Information Transfers New Exit Checklist Surveys Tasks Final Pay What’s New- Final Paycheck Off-Cycle On-Cycle UCPC • Involuntary Terminations • Non-Represented Employees • UCPC will process off-cycle • Voluntary Represented • Voluntary Terminated paychecks Employees • Employees will receive their • Same day paychecks will • SSC will request off-cycle final paychecks on their not be available. -

Do 516 (5/8/12)

CHAPTER: 500 Personnel/Human Resources DEPARTMENT ORDER: Arizona 516 – Employee Exit Interview and Exit Survey Department OFFICE OF PRIMARY RESPONSIBILITY: DD of Corrections Effective Date: December 13, 2019 Department Order Amendment: Manual N/A Supersedes: DO 516 (5/8/12) Scheduled Review Date: July 1, 2022 ACCESS ☐ Contains Restricted Section(s) David Shinn, Director CHAPTER: 500 516 – EMPLOYEE EXIT INTERVIEW AND EXIT SURVEY DECEMBER 13, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS PURPOSE ...................................................................................................................................... 1 APPLICABILITY .............................................................................................................................. 1 RESPONSIBILITY ............................................................................................................................ 1 PROCEDURES ................................................................................................................................ 1 1.0 ADMINISTRATIVE REQUIREMENTS ........................................................................................ 1 2.0 CONDUCTING THE EMPLOYEE EXIT INTERVIEW ..................................................................... 2 3.0 EXIT SURVEY PROCESS ....................................................................................................... 3 4.0 CONFIDENTIALITY ............................................................................................................... 3 FORMS LIST ................................................................................................................................. -

Resignation/Exit Interview of Professional Staff

Resignation/Exit Interview of #536.1 Professional Staff Exhibit Twin Lakes School Dist. #4 Page 1 of 2 The Twin Lakes School District recognizes the importance of promoting and maintaining personnel practices that foster constructive employee feedback and suggestions. To further the above goal, the superintendent will develop and implement a procedure to conduct exit interviews with employees who leave the employment of the school district. The superintendent or his/her designee will initiate the exit interview and completed interviews will be placed in the personnel file of the person leaving the district. The superintendent will also develop and implement an electronic exit survey that will be administered to the employee. The completed survey will also be saved in the personnel file of the employee. A copy of all exit interviews and surveys, subject to any applicable restrictions or redactions underneath state and federal law, will be available to the Board members at a closed session meeting. EXIT INTERVIEW POLICY AND PROCEDURES: The purpose of this policy is to identify workplace, organizational or human resources factors that have contributed to an employee's decision to leave employment; to enable the district to identify any trends requiring attention or any opportunities for improving the district's ability to respond to employee issues; and to allow the company to improve and continue to develop recruitment and retention strategies aimed at addressing these issues. This policy covers the procedures to be adopted when members of the district leave employment. SCOPE: This policy applies to all employees including employees taking early retirement and voluntary severance.