Performing Arts Centers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

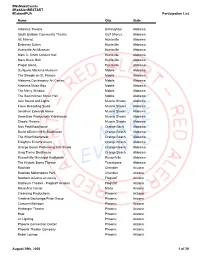

Participation List

#WeMakeEvents #RedAlertRESTART #ExtendPUA Participation List Name City State Alabama Theatre Birmingham Alabama South Baldwin Community Theatre Gulf Shores Alabama AC Marriot Huntsville Alabama Embassy Suites Huntsville Alabama Huntsville Art Museum Huntsville Alabama Mark C. Smith Concert Hall Huntsville Alabama Mars Music Hall Huntsville Alabama Propst Arena Huntsville Alabama Gulfquest Maritime Museum Mobile Alabama The Steeple on St. Francis Mobile Alabama Alabama Contempory Art Center Mobile Alabama Alabama Music Box Mobile Alabama The Merry Window Mobile Alabama The Soul Kitchen Music Hall Mobile Alabama Axis Sound and Lights Muscle Shoals Alabama Fame Recording Sudio Muscle Shoals Alabama Jonathan Edwards Home Muscle Shoals Alabama Sweettree Productions Warehouse Muscle Shoals Alabama Shoals Theatre Muscle Shoals Alabama Nick Pratt Boathouse Orange Bach Alabama David &DeAnn Milly Boathouse Orange Beach Alabama The Wharf Mainstreet Orange Beach Alabama Enlighten Entertainment Orange Beach Alabama Orange Beach Preforming Arts Studio Orange Beach Alabama Greg Trenor Boathouse Orange Beach Alabama Russellville Municipal Auditorium Russellville Alabama The Historic Bama Theatre Tuscaloosa Alabama Rawhide Chandler Arizona Rawhide Motorsports Park Chandler Arizona Northern Arizona university Flagstaff Arizona Orpheum Theater - Flagstaff location Flagstaff Arizona Mesa Arts Center Mesa Arizona Clearwing Productions Phoenix Arizona Creative Backstage/Pride Group Phoenix Arizona Crescent Ballroom Phoenix Arizona Herberger Theatre Phoenix -

Florida Presenters Fall Summit Attendee List

Florida Presenters Fall Summit Attendee List The Adrienne Arsht Center for the Performing Arts Oscar Quesada [email protected] Ellen Rusconi [email protected] Liz Wallace [email protected] Joanne Benko [email protected] G Young [email protected] Artis-Naples David Filner [email protected] T. McDevitt [email protected] J. Poppert [email protected] Arts Garage Marjorie Waldo [email protected] Ethan [email protected] Serena [email protected] ASM Global - Jacksonville (Ritz Theatre & Museum) Stacy Aubrey [email protected] J. Mahaley [email protected] B. McCoy [email protected] Aventura Arts & Cultural Center Jeff Kiltie [email protected] M. fulfaro [email protected] J. Lerner [email protected] Professional Facilities Management (Barbara B. Mann Performing Arts Hall) Scott Saxon [email protected] P. Welty [email protected] J. Iverson [email protected] Beaches Fine Arts Series Kathryn Wallis [email protected] Big 3 Entertainment (Mahaffey Theater) Joe Santiago [email protected] Big Arts Naomi Buck [email protected] M. Dest [email protected] W. Harriman [email protected] R. Jones [email protected] Friends of Boca Grande Community Center Debbie Frank [email protected] M. Howell [email protected] Broward Center for the Performing Arts Matthew Mcneil [email protected] Jill Kratish [email protected] J. Sierra Grobbelaar [email protected] T. Lessig [email protected] Center for the Arts at River Ridge Rick D'onofrio [email protected] Faith Brooks [email protected] Central Park Performing Arts Center Rob mondora [email protected] D. Pinto [email protected] J. Ingrao [email protected] Century Village Theaters / WPB, Boca Raton, Pembroke Pines Abby Koffler [email protected] M. -

Member Directory - Presenting Organization '62 Center for Theatre and Dance at Williams 92Nd St Y Harkness Dance Center College 1395 Lexington Ave

Member Directory - Presenting Organization '62 Center for Theatre and Dance at Williams 92nd St Y Harkness Dance Center College 1395 Lexington Ave. New York, NY 10128 Williams College, 1000 Main Street Tel: (212) 415-5555 Williamstown, MA 01267 http://www.92y.org Tel: (413) 597-4808 Sevilla, John-Mario, Director Fax: (413) 597-4815 [email protected] http://62center.williams.edu/62center/ Fippinger, Randal, Visiting Artist Producer and Outreach Manager [email protected] Academy Center of the Arts ACANSA Arts Festival 600 Main Street 621 East Capitol Avenue Lynchburg, VA 24504 Little Rock, AR 72202 US US Tel: (434) 528-3256 Tel: (501) 663-2287 http://www.academycenter.org http://acansa.org Wilson, Corey, Programming Manager Helms, Donna, Office Manager [email protected] [email protected] Adelphi University Performing Arts Center Admiral Theatre Foundation One South Avenue, PAC 237 515 Pacific Ave Garden City, NY 11530 Bremerton, WA 98337-1916 Tel: (576) 877-4927 Tel: (360) 373-6810 Fax: (576) 877-4134 Fax: (360) 405-0673 http://pac.adelphi.edu http://https://www.admiraltheatre.org/ Daylong, Blyth, Executive Director Johnson, Brian, Executive Director [email protected] [email protected] Admission Nation LLC Adrienne Arsht Center for the Performing Arts of 41 Watchung Plaza, Suite #82 Miami-Dade County Montclair, NJ 07042 1300 Biscayne Blvd US Miami, FL 33132-1430 Tel: (973) 567-0712 Tel: (786) 468-2000 http://admission-nation.com/ Fax: (786) 468-2003 Minars, Ami, Producer & Founder http://arshtcenter.org [email protected] Zietsman, Johann, President and CEO [email protected] Al Larson Prairie Center for the Arts Alabama Center for the Arts 201 Schaumburg Ct. -

Florida Department of State Division of Cultural Affairs (DCA) 2019-2020

Florida Department of State Division of Cultural Affairs (DCA) 2019-2020 Well-Vetted, Ranked, and Linked Matching Grant Recommendations for All Four DCA Grant-Funding Categories by Counties Florida County Grant Florida Department of State Division of Cultural Affairs (DCA) DCA 2019-2020 DCA Grants-Program Funding Categories Ranking Well-vetted and Recommended 2019-2020 Grant Applicants -- funding these Qualified & GPS = General Program Support qualified grant applicants is totally dependent upon the 2019 Florida Recommended SCP = Specific Cultural Project Legislature providing the necessary appropriations: State-Matching Grant Requests Do you want more information on each recommended DCA grant applicant? Click on the names below to access websites. ALACHUA 17 Total DCA 2019-2020 Qualified Matching Grant Requests from Alachua 377 Annasemble Community Orchestra of Gainesville Inc. $1,445 Cultural and Museum Grant for GPS Alachua 159 City of Gainesville / Parks, Recreation and Cultural Affairs Department $150,000 Cultural and Museum Grant for GPS Alachua 24 Dance Alive!, Inc. $85,860 Cultural and Museum Grant for GPS Alachua 444 Gainesville Fine Arts Association, Inc. $23,550 Cultural and Museum Grant for GPS Alachua 391 Gainesville Little Theater dba Gainesville Community Playhouse $40,000 Cultural and Museum Grant for GPS Alachua 126 Gainesville Youth Chorus, Inc. $35,000 Cultural and Museum Grant for GPS Alachua 135 Matheson History Museum $40,000 Cultural and Museum Grant for GPS Alachua 299 Santa Fe College / Cultural Programs $48,288 Cultural and Museum Grant for GPS Alachua 17 Shands Teaching Hospital and Clinics, Inc. $90,000 Cultural and Museum Grant for GPS Alachua 219 The Hippodrome State Theatre, Inc. -

Florida Department of State Division of Cultural Affairs' 2020-21 Ranked List of Cultural and Museum Matching-Grant Recommendations

Florida Department of State Division of Cultural Affairs' 2020-21 Ranked List of Cultural and Museum Matching-Grant Recommendations A. Florida B. DCA Cultural and Museum Matching-Grant C. Rank D. 2020-21 Florida Department of State (DOS) Division of Cultural Affairs (DCA) E 2020-21 DCA County of DCA Category for General Program Support (GPS) these on This Well-vetted, Recommended Matching-Grant Applicants Under This Category -- funding Recommended, 2020-21 Grant Ranked Matching-Grants Are Recommended for 2020- DCA these matching grants at their qualified recommended amounts under Column E is Qualified Matching- Applicants: 21 State Funding Under: List: dependent upon the 2020 Florida Legislature appropriating the funds and the State Grant Requests: Governor's approval: Miami-Dade Cultural & Museum Matching-Grant Request for GPS 1 Miami Dade College / Miami Book Fair Year Round $96,978 Orange Cultural & Museum Matching-Grant Request for GPS 2 MicheLee Puppets, Inc. $42,029 Miami-Dade Cultural & Museum Matching-Grant Request for GPS 3 Miami City Ballet, Inc. $150,000 Miami-Dade Cultural & Museum Matching-Grant Request for GPS 4 Miami-Dade County / Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Affairs $150,000 Miami-Dade Cultural & Museum Matching-Grant Request for GPS 5 Borscht Corp $61,530 Orange Cultural & Museum Matching-Grant Request for GPS 6 The University of Central Florida Board of Trustees $150,000 Monroe Cultural & Museum Matching-Grant Request for GPS 7 Key West Literary Seminar, Inc. $90,000 Miami-Dade Cultural & Museum Matching-Grant Request for GPS 8 University of Wynwood, Inc. / O, Miami $49,000 Sarasota Cultural & Museum Matching-Grant Request for GPS 9 The Hermitage Artist Retreat, Inc. -

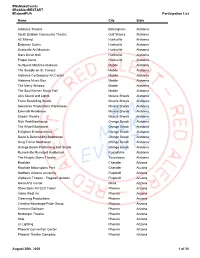

Participation List

#WeMakeEvents #RedAlertRESTART #ExtendPUA Participation List Name City State jkl; Alabama Theatre Birmingham Alabama South Baldwin Community Theatre Gulf Shores Alabama AC Marriot Huntsville Alabama Embassy Suites Huntsville Alabama Huntsville Art Museum Huntsville Alabama Mars Music Hall Huntsville Alabama Propst Arena Huntsville Alabama Gulfquest Maritime Museum Mobile Alabama The Steeple on St. Francis Mobile Alabama Alabama Contempory Art Center Mobile Alabama Alabama Music Box Mobile Alabama The Merry Window Mobile Alabama The Soul Kitchen Music Hall Mobile Alabama Axis Sound and Lights Muscle Shoals Alabama Fame Recording Studio Muscle Shoals Alabama Sweettree Productions Warehouse Muscle Shoals Alabama Edwards Residence Muscle Shoals Alabama Shoals Theatre Muscle Shoals Alabama Nick Pratt Boathouse Orange Beach Alabama The Wharf Mainstreet Orange Beach Alabama Enlighten Entertainment Orange Beach Alabama David & DeAnn Milly Boathouse Orange Beach Alabama Greg Trenor Boathouse Orange Beach Alabama Orange Beach Preforming Arts Studio Orange Beach Alabama Russellville Municipal Auditorium Russellville Alabama The Historic Bama Theatre Tuscaloosa Alabama Rawhide Chandler Arizona Rawhide Motorsports Park Chandler Arizona Northern Arizona university Flagstaff Arizona Orpheum Theater - Flagstaff location Flagstaff Arizona Mesa Arts Center Mesa Arizona Show Boss AV LED Trailer Phoenix Arizona Video West Inc Phoenix Arizona Clearwing Productions Phoenix Arizona Creative Backstage/Pride Group Phoenix Arizona Crescent Ballroom Phoenix Arizona -

Forum : Vol. 41, No. 01 (Spring : 2017)

University of South Florida Scholar Commons FORUM : the Magazine of the Florida Humanities Florida Humanities 4-1-2017 Forum : Vol. 41, No. 01 (Spring : 2017) Florida Humanities Council. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/forum_magazine Recommended Citation Florida Humanities Council., "Forum : Vol. 41, No. 01 (Spring : 2017)" (2017). FORUM : the Magazine of the Florida Humanities. 80. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/forum_magazine/80 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Florida Humanities at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FORUM : the Magazine of the Florida Humanities by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MAGAZINE OF THE FLORIDA HUMANITIES COUNCIL SPRING 2017 CHANGE IS COMING TO ‘FORGOTTEN’ FLORIDA DEVELOPMENT THREATENS MORE OF OLD MIAMI ALSO: HOW THE HUMANITIES ANCHOR DEMOCRACY 2017 Board of Directors letter FROM THE DIRECTOR B. Lester Abberger TALLAHASSEE Wayne Adkisson, Secretary PENSACOLA Juan Bendeck NAPLES Kurt Browning SAN ANTONIO Peggy Bulger FERNANDINA BEACH Gregory Bush MIAMI I AM A LARGO HIGH SCHOOL PACKER. We were David Colburn GAINESVILLE called the Packers because Largo was a packing center Sara Crumpacker MELBOURNE for Pinellas County’s robust citrus crop. But during th Brian Dassler TALLAHASSEE the last half of the 20 century—because of hard José Fernández, Treasurer ORLANDO freezes, rapid population growth, high land values, Casey Fletcher, Vice-Chair BARTOW and development—the county’s commercial citrus Linda Landman Gonzalez ORLANDO production ceased. An area once green and fragrant Joseph Harbaugh FORT LAUDERDALE with orange groves is now urban, and the local culture David Jackson TALLAHASSEE has changed to reflect that. -

Heat up the Holidays

JACKSONVILLE heat up the holidays Last Minute Gift Guide | Michelle’s Southern Home Cooking | The Heat is On with Rita Hayworth | Jim Brickman Interview free weekly guide to entertainment and more | december 13 - 19, 2007 | www.eujacksonville.com 2 december 13-19, 2007 | entertaining u newspaper COVER PHOTO FROM THE HEAT IS ON (see page 26 for story) table of contents feature Holiday Events ...............................................................................................PAGES 13-14 Last Minute Gifts ............................................................................................PAGES 15-19 movies Movies in Theaters this Week ...........................................................................PAGES 6-10 Alvin & The Chipmunks (movie review).................................................................... PAGE 6 I Am Legend (movie review) .................................................................................... PAGE 7 The Perfect Holiday (movie review) ......................................................................... PAGE 8 FireTrail (movie review) ........................................................................................... PAGE 9 Me Again Productions (local film director spotlight) ............................................... PAGE 10 home Netscapades ......................................................................................................... PAGE 12 Videogames ........................................................................................................ -

High Tech Gift Ideas Guide to Local Malls JACKSONVILLE

high tech gift ideas guide to local malls JACKSONVILLE holiday events golden symphony compass musicians book and film review speak out free weekly guide to entertainment and more | december 6 - 12, 2007 | www.eujacksonville.com 2 december 6-12, 2007 | entertaining u newspaper cover photo from sleeping beauty on ice (see page 32 for story) table of contents feature Hi-Tech Shopping ...........................................................................................PAGES 13-16 Tech Shopping Advice ....................................................................................... PAGE 14 Game Systems ................................................................................................. PAGE 16 Local Shopping Staples ..................................................................................PAGES 17-18 Holiday Events ...............................................................................................PAGES 20-21 movies Movies in Theaters this Week ...........................................................................PAGES 6-11 The Golden Compass (movie review) ...................................................................... PAGE 6 Awake (movie review) ............................................................................................. PAGE 8 Control (movie review) ............................................................................................ PAGE 9 International Film Festival (9th & Main) .............................................................PAGE 10-11 home His -

Florida Theatre and Florida Presenters Join #Redalertrestart, a Nationwide Call to Action Supporting the Live Performance Industry

Florida Theatre and Florida Presenters Join #RedAlertRESTART, A Nationwide Call to Action Supporting the Live Performance Industry Jacksonville, Fla. (August 28, 2020) – The Florida Professional Presenters Consortium, a statewide organization of over 60 performing arts venues, including the Florida Theatre in Jacksonville, is joining “Red Alert,” a nationwide effort to encourage Congress to provide relief for the live entertainment industry, which has been uniquely affected by the pandemic. On Tuesday night, September 1, 2020 from 9:00 p.m. to 12:00 midnight, performing arts venues across the nation and across Florida will light their exteriors in red as part of a nationwide call to action, imploring the US Congress to pass the RESTART Act (S. 3814/H.R. 7481) and the Save Our Stages Act (S. 4258/H.R. 7806) as quickly as possible. The Florida Theatre is working with colleagues at AVL Productions and Local 115 of the International Alliance of Stage Employees on this important call to action. The RESTART Act and the Save Our Stages Act offer economic relief to the live events industry, which has been shuttered since March, 2020. Red Alert also advocates for extending Pandemic Unemployment Assistance, to provide relief to those without work since March due to COVID-19. Nationwide, 12 million show workers are estimated to be unemployed because of Covid-19, including designers, technicians, programmers, stagehands and others. Numa Saisselin, President of Florida Theatre said, “Performing arts venues are closed because we know that Covid-19 spreads within intimate, closed spaces, which of course perfectly describes a theatre or club. -

County by County Allocations

COUNTY BY COUNTY ALLOCATIONS Conference Report on Senate Bill 2500 Fiscal Year 2019-2020 General Appropriations Act Florida House of Representatives Appropriations Committee May 22, 2019 County Allocations Contained in the Conference Report on Senate Bill 2500 2019-20 General Appropriations Act This report reflects only items contained in the Conference Report on Senate Bill 2500, the 2019-20 General Appropriations Act (GAA), which are identifiable to specific counties. State agencies will further allocate other funds contained in the General Appropriations Act based on authorized distribution methodologies. This report was produced prior to the veto process. This report includes all construction, right of way, or public transportation phases $1 million or greater that are included in the Tentative Work Program for Fiscal Year 2019-20. The report also contains projects included on certain approved lists associated with specific appropriations where the list may be referenced in proviso but the project is not specifically listed. Examples include, but are not limited to, lists for library, cultural, and historic preservation program grants included in the Department of State and for the Beach Management Funding Assistance Program (BMFAP) included in the Department of Environmental Protection. The Florida Education Finance Program (FEFP) and funds distributed to counties by state agencies at a later date are not identified in this report. Items in this report considered Appropriations Projects under Joint Rule Two are identified with either a House Bill (HB) number or a Senate Form number in the Project Title or the term “RBAP” is included under the Program description to indicate the item includes recurring base appropriations project (RBAP) funding.