University of Cape Town

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol. 15, No. 5 May 2011 You Can’T Buy It

ABSOLUTELY FREE Vol. 15, No. 5 May 2011 You Can’t Buy It Betty Anglin Smith Scott Upton Leo Twiggs Eva Carter Images from the exhibit, Contemporary Carolinas, an invitational exhibition by a dynamic group of contemporary artists in the Carolinas, on view at Smith Killian Fine Art in Charleston, SC, on view from May 6 through June 12, 2011. A reception will be held on May 6, from 5-8pm. (See article on Page 14). Carolina Arts, is published monthly by Shoestring Publishing Company, a subsidiary TABLE OF CONTENTS of PSMG, Inc. Copyright© 2011 by PSMG Inc. It also publishes the blogs Carolina This index has active links, just click on the Page number and it will take you to that page. Arts Unleashed and Carolina Arts News, Copyright© 2011 by PSMG, Inc. All rights reserved by PSMG, Inc. or by the authors of articles. Reproduction or use without written Page 1 - Cover, work from Smith Killian Fine Art Page 2 - Table of Contents, Contact Info, Facebook Link, Links to blogs and Carolina Arts website permission is strictly prohibited. Carolina Arts is available online at (www.CarolinaArts. Page 3 - Ad by Morris Whiteside Galleries com). Mailing address: P.O. Drawer 427, Bonneau, SC 29431. Telephone: 843/825-3408, Page 4 - Ad by Smith Galleries & The Sylvan Gallery, and Editorial Commentary e-mail at ([email protected]) and on the web at (www.CarolinaArts.com). Page 5 - Ads by Sculpture in the South & Inkpressions/Photographic Page 6 - Article about North Charleston Arts Festival Editor/Publisher/Calendars/Distribution Page 7 - Ads by Peter Scala & Charleston Crafts Co-op, articles cont. -

Retailer List for Website

RETAILER STREET ADDRESS CITY Just Save NC HWY 705 Robbins Lowes Foods S. Main St Archdale The Wet Whistle E Bonnie Place Archdale Lowes Foods Dixie Dr Asheboro The Table Bakery South Church Street Asheboro Blue Deer Cookies U.S. Hwy 321 South Blowing Rock Lowes Foods University Dr Burlington JOHNNY'S W. Main Street Carrboro Weaver Street Market E. Weaver St Carrboro Weaver Street Market Market St Chapel Hill Earl's Grocery Elizabeth Avenue Charlotte Just Save Sunset Rd Gboro Charlotte Bulldega Urban Market West Parrish Street Durham Durham Co-Op Market West Chapel Hill Street Durham Obatco Blackwell Street Durham Graham Soda Shop N. E. Court Square Graham Just Save S. Main St Graham Blake Farms Blakeshire Road Greeensboro Bestway Walker Ave. Greensboro Cheesecakes by Alex S Elm Street Greensboro Deep Roots North Eugene Street Greensboro Food Lion Woody Mill Road Greensboro Fresh Market Lawndale Dr Greensboro Fresh Market Highwoods Dr Greensboro Ghassan's Battleground Ave Greensboro Lowes Foods New Garden Rd Greensboro Marketplace West Gate City Blvd Greensboro Maxie B's Battleground Ave. Greensboro Savor The Moment Coliseum Blvd Greensboro The Table On Elm South Elm Street Greensboro Town and Country Meat & Produce W Vandalia Road Greensboro Whole Foods W.Friendly Ave Greensboro Debeen Espresso W Lexington Ave High Point Weaver Street Market S. Churchton St Hillsborough McLeod Organics Davidson-Concord Highway Huntersville Junktique Allyway 115 South Main Street Kernersville Musten and Crutchfield N. Main Street Kernersville Lewisville Country Store 6373 Shallowford Road Lewisville Food Lion W. Swannanoa Ave. Liberty Liberty Food Mart 3901 Allamance Church Rd. -

Specialty Grocery Stores Food Lion EUROPEAN 2000 Chapel Hill Rd

Supermarkets near Duke University (Check websites for a complete listing of locations) Specialty Grocery Stores Food Lion www.foodlion.com EUROPEAN 2000 Chapel Hill Rd. 27707 919.402.0190 2930 W Main St. 27705 919.286.0400 Guglhupf Bakery & Patesserie (German) 4621 Hillsborough Rd. 27705 919.309.0385 2706 Durham-Chapel Hill Blvd., 27707 919.401.2600 www.guglhupf.com Harris Teeter www.harristeeter.com Halgo-European Deli & Groceries (Eastern Europe) 2107 Hillsborough Rd. 27705 919.286.1500 4520 South Alston Ave., Durham 27713 1817 MLK Jr Pkwy. 27707 919.489.9887 919.321.2014 1501 Horton Rd.,27705 919.471.1938 www.halgo-durham.com Kroger Mariakakis Food & Wine (Greek) www.kroger.com 1322 Fordham Blvd., Chapel Hill 27514 3457 Hillsborough Rd. 27705 919.383.2249 919.942.1453 1802 North Pointe Dr. 27705 919.220.5761 ASIAN/SOUTH ASIAN/EAST ASIAN SuperTarget www.target.com Little India (South Asian) 4037 Durham Chapel Hill Blvd. 27707 919.765.0008 919.489.9084 4201 University Dr., Ste. 110, Durham 27707 Whole Foods Organic Supermarket www.littleindiastore.com www.wholefoodsmarket.com 621 Broad St. 27705 919.286.2290 Li Ming’s Global Market (East Asian) 81 S Elliott Dr., Chapel Hill 27514 919.968.1983 919.401.5212 3400 Westgate Dr., Durham 27707 (Across from SuperTarget) They have Chinese food court inside. Specialty Grocery Stores Spice Bazaar (South Asian) 919.490.3747 Middle Eastern 4125 Durham-Chapel Hill Blvd. (on service road), 27707 Taiba Market (Halal Meat) www.spicebazaarnc.com 1008 West Chapel Hill St., Durham 27707 919.219.7120 Around the World Market (Indian) MEXICAN 919.572.5599 1708 E. -

First Name Last Name Organization City State Country Sue Sturman

First Name Last Name Organization City State Country Sue Sturman Academie Opus Caseus Brookline MA Olivier Beaulieu-Charbonneau Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Ottawa ON Canada Dale Martin Agri-Service LLC Hagerstown MD Larry Wampler Agri-Service LLC Hagerstown MD Stephanie Lopez AIB International Manhattan KS Keith Adams Alemar Cheese Company Mankato MN Craig Hageman Alemar Cheese Company Mankato MN Bill Kynast Alouette Cheese USA LLC Ridgefield CT Bill Stuart Alpine Slicing & Cheese Conversion Monroe WI Roxanne O'Brien American River College/Chef Instructor Sacramento CA Carlos Souffront Andronico's Community Markets San Leandro CA Annie Hall Annie Hall, Inc. Boca Raton FL John Antonelli Antonelli's Cheese Shop Austin TX Kendall Antonelli Antonelli's Cheese Shop Austin TX Kara Chadbourne Antonelli's Cheese Shop Austin TX Victoria Swaynos Antonelli's Cheese Shop Austin TX Louise Converse Artisan Cheese Company Sarasota FL Angela Jenkins Artisan Cheese Company Sarasota FL Davee Benson Atalanta Corporation Austin TX Cheré Hedges Atalanta Corporation Folsom CA Chris Huey, CCP Atalanta Corporation Wedowee AL Michael Meadows Atalanta Corporation Tualatin OR John Rodger Atalanta Corporation Elizabeth NJ John Stephano Atalanta Corporation Elizabeth NJ Kathy Ziesemer Atalanta Corporation Houston TX Gerry Albright ATC-USA, LLC Wellesley Island NY Alison Lansley Australian Specialist Cheesemakers' Association Melbourne VIC Australia Brennan Buckley Avalanche Cheese Co. Basalt CO Kevin McCullen Avalanche Cheese Co. Basalt CO Emilie Villmore Bacco's -

AGING WELL TOGETHER: NURTURING the BODY Faith, Aging, & Nutrition: a How-To Senior Nutrition Guidebook

AGING WELL TOGETHER: NURTURING THE BODY Faith, Aging, & Nutrition: A How-To Senior Nutrition Guidebook 11/1/2015 This Guidebook is a cooperative effort between the Orange County Department of Aging Project Engage Senior Resource Team, and members of the Orange County faith community. Together, we seek solutions to the nutritional challenges experienced by Orange County older adults intending to age in place. This Guide identifies some of the difficulties, describes available services, and provides guidance and inspiration to faith and community based organizations interested in incorporating senior nutrition into their care and compassion ministries. Aging well together: Nourishing the Body Faith, Aging and Nutrition: A How-to Guidebook TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Seniors may not be eating well for many reasons. But, Faith and Community INTRODUCTION Based Organizations, neighbors, adult children of seniors, and caregivers can become more aware of nutritional obstacles to successfully address them. 1.1 Why this guide was written 1.2 How to get the most from the guide 2.0 As we age we may experience challenges to getting food, including: limited OBTAINING finances, difficulty walking and/or carrying heavy, bulky packages, poor vision, decreasing stamina, the social stigma of “taking too long at the FOOD checkout,” and changing food tastes. However, Orange County seniors have several options. 2.1 Groceries and big box stores 2.2 Farmers Markets 2.3 Food Trucks and The LoMo Market 2.4 Community Gardens & Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) 2.5 -

First Name Last Name Organization City State/Province Country Dave Selden 33 Books Co

First Name Last Name Organization City State/Province Country Dave Selden 33 Books Co. Portland OR Jennifer Swift 34 Degrees Denver CO Sue Sturman Academie Opus Caseus Brookline MA Tess Peterson Admiral Cheese Brookline MA Lori Chavez ADW Acosta Livermore CA Olivier Beaulieu-Charbonneau Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Ottawa ON Dale Martin Agri-Service LLC Hagerstown MD Larry Wampler Agri-Service LLC Hagerstown MD Stephanie Lopez AIB International Manhattan KS Thomas Milhoua Air Quality Process Artix France Keith Adams Alemar Cheese Company Mankato MN Craig Hageman Alemar Cheese Company Mankato MN Christine Velez Alouette Cheese Fairfield NJ Bill Stuart Alpine Slicing & Cheese Conversion Monroe WI Roxanne O'Brien American River College Sacramento CA Myla Holmes Amy's Kitchen Santa Rosa CA Emily Morgan Ancient Heritage Dairy Portland OR Ronda Danley ANCO Fine Cheese Ormond Beach FL Hannah Thompson ANCO Fine Cheese Atlanta GA Soyoung Scanlan Andante Dairy San Francisco CA Erna André ANDRE ARTISAN CHEESE Bodega CA Carlos Souffront Andronico's Community Markets San Leandro CA Beth Spitler Animal Welfare Approved Oakland CA Annie Hall Annie Hall, Inc. Boca Raton FL John Antonelli Antonelli's Cheese Shop Austin TX Kendall Antonelli Antonelli's Cheese Shop Austin TX Kara Chadbourne Antonelli's Cheese Shop Austin TX Victoria Swaynos Antonelli's Cheese Shop Austin TX Sue Langstaff Applied Sensory, LLC Fairfield CA Elena Santogade Arethusa Farm & Dairy Litchfield CT Patrick Collins Arla Foods Canada Toronto ON Christophe Megevand Arthur Schuman -

View O O O O O O O O O O

" "“qu THE HISTORICAL DEV ELOPM E NT 0? F000 DtsTRmUTDON BY GORDON LOREN COOK JR 1961 m _._ THEME ”Irmgu'qnjw‘WWW 7 01390 4499 LEBRARY Michigan State University PLACE IN RETURN BOX to romavo this chockout from your record. TO AVOID FINES return on or before date duo. [m DATE DUE DATE DUE DATE DUE .Q I a __J |L__J| |L__I l JL _J 1— 7 __JL__ ___l MSU Is An Namath. Action/Equal Opponunfly IMW WmG-pd THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF FOOD DISTRIBUTION by Gordon Loren Cook, Jr. A THESIS Submitted to the College of Business and Public Service Michigan State University of Agriculture and Applied Science in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of General Business Curriculum in Food Distribution June, 1961 TABLE OF CONTENTS m I INTRODUCTION Purpose of Thesis ................................ Importance ofthe Study ... Limitations ..... 0.0.00.0...00. 00000000 ...... ..... Definitions 0 O O O O O O 0 O O 0 O 0 0 O O . 0 O 0 0 O 0 0 O 0 0 0 O 0 O 0 O 0 O 0 O 0 0 0 MethOdOIOgY 00000 0 O O 0 0 . O 0 0 . 0 O 0 0 0 0 . 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 O 0 0 0 0 0 . PreView O O O O O O O O O O . O . 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 O O 0 O O 0 O 0 0 0 O 0 0 0 O 0 D 0 0 C O‘O‘WNNH I I MINOR FOOD DISTRIBUTION SEGMENTS Consumer CooPerative Groups . -

FMI Member Search Results

FMI Member Search Results This search was performed on Oct 02 2021 at 01:20 AM The search criteria selected were as follows. If you find information that needs to be updated, please email [email protected]. Thank you. FMI 2345 Crystal Drive, Suite 800 Arlington, VA 22202 Phone: 202.452.8444 | Fax: 202.429.4519 84.51º 100 W. Fifth Street Cincinnati, OH 45202-2704 United States Main Phone: 513-632-0903 Web site: www.8451.com E-mail: [email protected] Description At 84.51º, we are obsessed with turning data into knowledge. By taking a unique longitudinal, long-term approach to data analytics, we provide a whole new depth of understanding and a higher level of insight for the partners and consumer brands we serve. We help our partners embed a customer-first attitude deeply (and broadly) throughout the organization to drive growth and enhance customer loyalty. (Parent Company: The Kroger Co.) A.J. Letizio Sales & Marketing, Inc. 55 Enterprise Drive Windham, NH 03087-2031 United States Main Phone: 603-894-4445 Web site: www.ajletizio.com Abundance Cooperative Market 571 South Avenue Rochester, NY 14620-1335 United States Main Phone: 585-454-2667 Web site: www.abundance.coop E-mail: [email protected] (Parent Company: National Co+op Grocers) Acme Fresh Markets 2700 Gilchrist Road Akron, OH 44305-4433 United States Main Phone: 330-733-2263 ext.55318 Web site: www.acmestores.com Description Acme is great (Parent Company: The Fred W. Albrecht Grocery Co.) ACME Markets 75 Valley Stream Parkway Malvern, PA 19355-1459 United States Main Phone: 610-889-4000 Web site: www.acmemarkets.com (Parent Company: Albertsons Companies) Action Food Sales, Inc. -

(Jr) Day Celebration, Chapel Hill; UNC Office of Minority Affairs

Updated 7/3/19 Chapel Hill/Orange County Visitors Bureau Chapel Hill, Carrboro, Hillsborough, NC www.visitchapelhill.org 1-888-968-2060 2019 MAJOR ANNUAL EVENTS Check back often as events marked TBA are updated with dates, times and costs. January January 20-24. Martin Luther King Jr Day Weeklong Celebration, UNC Campus, Chapel Hill. Sponsor: UNC Diversity and Inclusion at https://diversity.unc.edu/programs/mlk/ (919) 962-6962. February February 14-16. 42nd Annual Carolina Jazz Festival, Locations on the UNC Campus, Chapel Hill; Sponsor UNC Department of Music (919) 962-1039 http://music.unc.edu/jazzfest February 16. Revolutionary War Living History Day, Revolutionary War Reenactment at the historic Alexander Dickson House. Sponsored by the Alliance for Historic Hillsborough, 10 am – 4 pm. (919) 732- 7741. www.visithillsboroughnc.com February 24. 2019 LIGHT UP Chinese New Year Festival, 140 West Franklin Street and Carolina Square, Downtown Chapel Hill. 11 am – 5 pm. The Third Annual Festival is hosted by the Chinese School at Chapel Hill to celebrate cultural diversity and the Chinese New Year with all communities in Chapel Hill and the surrounding areas. The Festival features lantern decorating with local artists, highly interactive art and craft creations, a dragon dance workshop, drumming and dragon dance performances, Peking Opera, games and prizes, exhibitions and workshop, silent auction, Asian food stands and trucks. When the twilight sets in, join your family, neighbors and friends in a thousand-lantern parade to usher in the New Year. Free Admission, however donations accepted. [email protected], www.chlightup.org March March 16. -

Our Community Market: a New Kind of Food Store

Our Community Market: A New Kind of Food Store A Feasbility Study Prepared by: The ICA Group 1330 Beacon St., Suite 355 Brookline, MA 02446 www.ica-group.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... iii Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... iv Our Community Market: A New Kind of Food Store ........................................................................ 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Store Overview ................................................................................................................................ 3 Value Proposition ............................................................................................................................. 3 Competitive Landscape .................................................................................................................... 5 Cost Structure .................................................................................................................................. 6 Distribution ...................................................................................................................................... 9 Our Community Market Produce Prices ..................................................................................... -

Community Profile

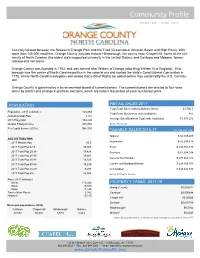

Community Profile UPDATED: JUNE 2018 Centrally located between the Research Triangle Park and the Triad (Greensboro, Winston-Salem and High Point). With more than 140,000 residents, Orange County includes historic Hillsborough, the county seat; Chapel Hill, home of the Uni- versity of North Carolina (the oldest state-supported university in the United States); and Carrboro and Mebane, former railroad and mill towns. Orange County was founded in 1752, and was named after William of Orange (also King William III of England). Hills- borough was the center of North Carolina politics in the colonial era and hosted the state's Constitutional Convention in 1778, where North Carolina delegates demanded that a Bill of Rights be added before they would ratify the U.S. Constitu- tion. Orange County is governed by a seven-member board of commissioners. The commissioners are elected to four-year terms by district and at-large in partisan elections, which are held in November of even-numbered years. POPULATION RETAIL SALES 2017 Total Retail Sales (with food/drink) ($1mil) $1,706.7 Population - 2017 (estimate) 143,264 Total Retail Businesses (with food/drink) 881 Annual Growth Rate 1.3% Average Sales/Business Total (with food/drink) $1,937,272 2018 Projection 144,820 Median Family Income $75,056 Source: NC Access Per Capita Income (2015) $55,338 TAXABLE SALES 2016-17 $1,726,191,488 Apparel $ 52,845,025 AGE DISTRIBUTION 2017 Median Age 35.3 Automotive $ 92,290,818 2017 Total Pop 0-19 34,368 Food $ 380,708,875 2017 Total Pop 20-24 17,428 Furniture $ 62,594,254 2017 Total Pop 25-34 19,261 General Merchandise $ 377,863,249 2017 Total Pop 35-44 16,329 2017 Total Pop 45-54 18,639 Lumber and Building Material $ 224,365,543 2017 Total Pop 55-59 9,281 Unclassified $ 534,074,373 2017 Total Pop 60+ 26,958 Source: NC Dept. -

Edizione 2015/2016 Agricoltura, Alimentazione E Sostenibilita'

EDIZIONE 2015/2016 AGRICOLTURA, ALIMENTAZIONE E SOSTENIBILITA' L’evoluzione del commercio mondiale dalla prima rivoluzione industriale al mondo contemporaneo Franco Fava M. E. C. C. (Museo e Laboratorio Europeo del Commercio e dei Consumatori) Documento di livello: C Franco A. Fava (Curatore del M.E.C.C. - [email protected]) Il commercio in vetrina Il Museo & Laboratorio Europeo del Commercio e dei Consumatori (M.E.C.C.) "Per comprendere il presente e progettare il futuro, bisogna inevitabilmente studiare il passato" Nonostante l'importanza sociale rivestita dal commercio, evidenziata nelle principali fasi di evoluzione storica ed economica, nonché la sua dimensione assunta negli ultimi cinquant'anni dall'avvio del commercio contemporaneo, attraverso lo sviluppo della grande distribuzione organizzata (GDO), ancora oggi si rilevano carenze di ricerca e studio, relativamente ai fenomeni socio-economici correlati ai nuovi format commerciali. “La révolution commerciale du 20° siècle est le prolongement de la révolution industrielle du 19° siècle. ” (Bernardo Trujillo). Le grandi manifatture prima e l'industria Taylor-fordista poi, nel percorso evolutivo tra la prima e la seconda rivoluzione industriale, sono state oggetto di studio e di approfondite analisi in molti campi delle scienze storiche e sociali (la sociologia e l'economia in primis), nonché la storia d'impresa è stata, per molte di queste realtà, celebrata tramite importanti musei e fondazioni culturali, al fine di trasmettere alle future generazioni la cultura aziendale e la