Foreign Farm Workers in Ontario: Representations in the Newsprint Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Movie-Going on the Margins: the Mascioli Film Circuit of Northeastern Ontario

Movie-Going on the Margins: The Mascioli Film Circuit of Northeastern Ontario A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY JESSICA LEONORA WHITEHEAD GRADUATE PROGRAM IN COMMUNICATION AND CULTURE YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO February 2018 © Jessica Leonora Whitehead 2018 ii Abstract Northeastern Ontario film exhibitor Leo Mascioli was described as a picture pioneer, a business visionary, “the boss of the Italians,” a strikebreaker and even an “enemy alien” by the federal government of Canada. Despite these various descriptors, his lasting legacy is as the person who brought entertainment to the region’s gold camps and built a movie theatre chain throughout the mining and resource communities of the area. The Porcupine Gold Rush—the longest sustained gold rush in North America—started in 1909, and one year later Mascioli began showing films in the back of his general store. Mascioli first came to the Porcupine Gold Camp as an agent for the mining companies in recruiting Italian labourers. He diversified his business interests by building hotels to house the workers, a general store to feed them, and finally theatres to entertain them. The Mascioli theatre chain, Northern Empire, was headquartered in Timmins and grew to include theatres from Kapuskasing to North Bay. His Italian connections, however, left him exposed to changes in world politics; he was arrested in 1940 and sent to an internment camp for enemy aliens during World War II. This dissertation examines cinema history from a local perspective. The cultural significance of the Northern Empire chain emerges from tracing its business history, from make-shift theatres to movie palaces, and the chain’s integration into the Hollywood-linked Famous Players Canadian national circuit. -

Annual Report 2019

Newcomer Tour of Norfolk County Student Start Up Program participants Tourism & Economic Development Annual Report 2019 Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 3 Business Incentives & Supports ...................................................................................... 5 Investment Attraction ..................................................................................................... 11 Collaborative Projects ................................................................................................... 14 Marketing & Promotion .................................................................................................. 20 Strategy, Measurement & Success ............................................................................... 31 Performance Measurement ........................................................................................... 32 Advisory Boards ............................................................................................................ 33 Appendix ....................................................................................................................... 35 Staff Team ..................................................................................................................... 40 Prepared by: Norfolk County Tourism & Economic Development Department 185 Robinson Street, Suite 200 Simcoe ON N3Y 5L6 Phone: 519-426-9497 Email: [email protected] www.norfolkbusiness.ca -

Norfolk Rotary Clubs with 90+ Years of Community Service!

ROTARY AROUND THE WORLD IS OVER 100 YEARS OLD IN NORFOLK COUNTY ROTARY HAS SERVED THE COMMUNITY ROTARY CLUB OF FOR SIMCOE ROTARY CLUB OF OVER DELHI ROTARY CLUB NORFOLK SUNRISE YEARS90! NORFOLK ROTARACT CLUB 2 A Celebration of Rotary in Norfolk, June 2018 Welcome to the world of Rotary Rotary in Norfolk County Rotary International is a worldwide network of service clubs celebrating in Norfolk more than 100 years of global community service with a convention in Toronto at the end of June. Among the thousands of attendees will be PUBLISHED BY representatives from Norfolk County’s three clubs, as well as an affiliated Rotary Club of Simcoe, Rotary Club of Delhi, Rotary Club of Norfolk Sunrise and Rotaract Club in Norfolk Rotaract Club. ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER Rotary has had a presence in Norfolk County for more than 90 years. Media Pro Publishing Over that time, countless thousands of dollars have been donated to both David Douglas PO Box 367, Waterford, ON N0E 1Y0 community and worldwide humanitarian projects. 519-429-0847 • email: [email protected] The motto of Rotary is “Service Above Self” and local Rotarians have Published June 2018 amply fulfilled that mandate. Copywright Rotary Clubs of Norfolk County, Ontario, Canada This special publication is designed to remind the community of Rotary’s local history and its contributions from its beginning in 1925 to the present. Rotary has left its mark locally with ongoing support of projects and services such as Norfolk General Hospital, the Delhi Community Medical Centre and the Rotary Trail. Equally important are youth services and programs highlighted by international travel opportunities. -

2002 Annual Report Our Year at a Glance

Torstar Corporation 2002 Annual Report Our Year at a Glance Financial Highlights 1 Message from the Chairman 2 To Our Shareholders 4 Newspapers Torstar Media Group 7 Toronto Star 8 Metroland 10 Regional Dailies 12 Harlequin Enterprises 15 Management’s Discussion and Analysis 19 Consolidated Financial Statements 28 Notes 32 Seven-Year Highlights 42 Corporate Information 43 he Annual Meeting of Shareholders will be held Wednesday, April 30, 2003 at the Metro Convention Centre, 255 Front Street West, Toronto, Room 206, beginning at 10 a.m. It will also be Webcast live on Ttmgtv.ca with interactive capabilities. Torstar Corporation is a broadly based-media company listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange (TS.B). Its businesses include daily newspapers led by the Toronto Star, Canada’s largest daily newspaper, The Hamilton Spectator, The Record (Kitchener, Cambridge and Waterloo), the Guelph Mercury, and their Internet-related businesses; Metroland Printing, Publishing & Distributing, publishers of approximately 70 community newspapers in Southern Ontario; and Harlequin Enterprises, a leading global publisher of women’s fiction. “The Board of Directors is extremely pleased that the baton of leadership has passed so smoothly and successfully.” John R. Evans Chairman, Board of Directors MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN n May 1, 2002, Robert Prichard assumed responsibility as Chief Executive Officer, having joined Torstar in May, 2001 as President of the Torstar Media Group. The Oseamless transition of leadership was made possible by the strong sense of shared stewardship with David Galloway, retiring CEO. It will come as no surprise to anyone who has worked with Robert Prichard that he has addressed his new responsibilities with unmatched energy and enthusiasm and demonstrated the steepest possible learning curve in gaining an appreciation of each of the businesses of Torstar. -

2011-2012 CJFE's Review of Free Expression in Canada

2011-2012 CJFE’s Review of Free Expression in Canada LETTER FROM THE EDITORS OH, HOW THE MIGHTY FALL. ONCE A LEADER IN ACCESS TO INFORMATION, PEACEKEEPING, HUMAN RIGHTS AND MORE, CANADA’S GLOBAL STOCK HAS PLUMMETED IN RECENT YEARS. This Review begins, as always, with a Report Card that grades key issues, institutions and governmental departments in terms of how their actions have affected freedom of expres- sion and access to information between May 2011 and May 2012. This year we’ve assessed Canadian scientists’ freedom of expression, federal protection of digital rights and Internet JOIN CJFE access, federal access to information, the Supreme Court, media ownership and ourselves—the Canadian public. Being involved with CJFE is When we began talking about this Review, we knew we wanted to highlight a major issue with a series of articles. There were plenty of options to choose from, but we ultimately settled not restricted to journalists; on the one topic that is both urgent and has an impact on your daily life: the Internet. Think about it: When was the last time you went a whole day without accessing the membership is open to all Internet? No email, no Skype, no gaming, no online shopping, no Facebook, Twitter or Instagram, no news websites or blogs, no checking the weather with that app. Can you even who believe in the right to recall the last time you went totally Net-free? Our series on free expression and the Internet (beginning on p. 18) examines the complex free expression. relationship between the Internet, its users and free expression, access to information, legislation and court decisions. -

Summer 2015 • Published at Vittoria, Ontario (519) 426-0234

SOME OF THE STUFF INSIDE 2015 Spaghetti Dinner & Auction 15 Flyboarding at Turkey Point 31 Smugglers Run 31 2015 OVSA Recipients 27 Happy 75th Anniversary 12 Snapd at the Auction 34 2015 Volunteers & Contributors 2 In Loving Memory of Ada Stenclik 30 Snapping Turtles 28 3-peat Canadian Champions 5 James Kudelka, Director 10 South Coast Marathon 30 Agricultural Hall of Fame 4 Lynn Valley Metal Artist 9 South Coast Shuttle Service 20 Alzheimer’s in Norfolk 14 Memories 3,32 St. Michael’s Natural Playground 21 Art Studio in Port Ryerse 15 MNR Logic 6 Tommy Land & Logan Land 11 Artist Showcase 14 North Shore Challenge 29 Vic Finds a Gem 14 Calendar of Events 36 Port Dover Pirates Double Champs 17 Vittoria Area Businesses 22 Carrie in OCAA Hall of Fame 8 Qigong in Port Ryerse 19 Walsh Volleyball Champs 13 Down Memory Lane 7 Radical Road Zipline 20 Zack Crandall First in Great Race 17 NO. 37 – SUMMER 2015 • PUBLISHED AT VITTORIA, ONTARIO (519) 426-0234 The Vittoria Booster The Vittoria Booster Newsletter is published twice a year by The Vittoria & District Foundation for its Members and Contributors. Booster e-mail: [email protected] website: http://www.vittoria.on.ca Foundation e-mail: [email protected] A n in front of a person’s name indicates that he or she is a member of The Vittoria & District Foundation Milestone Birthdays Celebrated nnWillie Moore, 75 on January 7 In Memoriam nnAda Stenclik, 100 on January 10 nnRoss Broughton, 85 on January 25 Howard John (Jack) King, æ 60, on January 18 nnEvelyn Oakes, 85 on January 31 R. -

Our Society Lacks Consistently Defined Attitudes

‘OUR SOCIETY LACKS CONSISTENTLY DEFINED ATTITUDES TOWARDS THE BLACK BEAR’: THE HISTORY OF BLACK BEAR HUNTING AND MANAGEMENT IN ONTARIO, 1912-1987 by MICHAEL COMMITO, B.A. (HONS), M.A. McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2015) Hamilton, Ontario (History) TITLE: ‘Our society lacks consistently defined attitudes towards the black bear’: The History of Black Bear Hunting and Management in Ontario, 1912-1987 AUTHOR: Michael Commito, B.A. (Hons) (Laurentian University), M.A. (Laurentian University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Ken Cruikshank NUMBER OF PAGES: vii, 282 ii ABSTRACT What kind of animal was a black bear? Were black bears primarily pests, pets, furbearers or game animals? Farmers, conservationists, tourists, trappers, and hunters in early twentieth- century Ontario could not agree. Even as the century progressed, ideas about bears remained twisted and there was often very little consensus about what the animal represented. These varying perceptions complicated the efforts of the provincial Department of Game and Fisheries and its successor agencies, the Department of Lands and Forests and the Ministry of Natural Resources, to develop coherent bear management policies. Perceptions about black bears often conflicted and competed with one another and at no one time did they have a single meaning in Ontario. The image of Ontario’s black bears has been continuously negotiated as human values, attitudes, and policies have changed over time. As a result, because of various and often competing perspectives, the province’s bear management program, for most of the twentieth century, was very loose and haphazard because the animal had never been uniformly defined or valued. Examining the history of these ambiguous viewpoints towards the black bear in Ontario provides us with a snapshot of how culture intersects with our natural resources and may pose challenges for management. -

QUARTERLY REPORT to MEMBERS, SUBSCRIBERS and FRIENDS FIRST QUARTER, 2012 Q1 Highlights: Effective and Efficient Policy Research & Outreach

QUARTERLY REPORT TO MEMBERS, SUBSCRIBERS AND FRIENDS FIRST QUARTER, 2012 Q1 highlights: effective and efficient policy research & outreach Policy Research • 13 research papers • 2 Monetary Policy Council Releases Policy Events • 7 policy roundtables (Toronto and Calgary), including the Annual Mintz Economic Lecture featuring Harvard professor Edward Glaeser • Inaugural Patrons Circle Dinner featuring GE CEO Jeffrey Immelt • Executive Briefing by leading China experts • 2 Monetary Policy Council meetings Policy Outreach • 14 policy outreach presentations • 54 citations in the National Post and Globe and Mail • 99 media outlets cited the Institute • 54 media interviews In April the Donner Canadian Foundation announced that the Institute’s groundbreaking • 25 opinion and editorial pieces study of immigration policy reform is one of four finalists for the 2011/12 Donner Prize. 2 Q1 Institute appointments • Philip Cross, until recently the Chief Economic Analyst at Statistics Canada, was appointed as a Senior Fellow, focusing on the study of business cycles and economic indicators. • John Curtis was appointed as a Senior Fellow specializing in international trade and economic policy. His past positions in Canada include Economic Briefing Officer to the Prime Minister, Advisor to the Anti-Inflation Board, the first Coordinator of Regulatory Reform, the Canadian Intellectual Property Negotiator in the Canada-US Free Trade Negotiations, and the founding Chief Economist within the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. • Michael Smart, Professor of Economics at the University of Toronto, a Fellow of the Oxford Centre for Business Taxation and of CESifo at the University of Munich, was appointed as a Fellow-in-Residence focusing on fiscal and tax policy. -

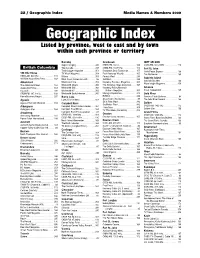

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance. -

Cotwsupplemental Appendix Fin

1 Supplemental Appendix TABLE A1. IRAQ WAR SURVEY QUESTIONS AND PARTICIPATING COUNTRIES Date Sponsor Question Countries Included 4/02 Pew “Would you favor or oppose the US and its France, Germany, Italy, United allies taking military action in Iraq to end Kingdom, USA Saddam Hussein’s rule as part of the war on terrorism?” (Figures represent percent responding “oppose”) 8-9/02 Gallup “Would you favor or oppose sending Canada, Great Britain, Italy, Spain, American ground troops (the United States USA sending ground troops) to the Persian Gulf in an attempt to remove Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq?” (Figures represent percent responding “oppose”) 9/02 Dagsavisen “The USA is threatening to launch a military Norway attack on Iraq. Do you consider it appropriate of the USA to attack [WITHOUT/WITH] the approval of the UN?” (Figures represent average across the two versions of the UN approval question wording responding “under no circumstances”) 1/03 Gallup “Are you in favor of military action against Albania, Argentina, Australia, Iraq: under no circumstances; only if Bolivia, Bosnia, Bulgaria, sanctioned by the United Nations; Cameroon, Canada, Columbia, unilaterally by America and its allies?” Denmark, Ecuador, Estonia, (Figures represent percent responding “under Finland, France, Georgia, no circumstances”) Germany, Iceland, India, Ireland, Kenya, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Malaysia, Netherlands, New Zealand, Pakistan, Portugal, Romania, Russia, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, Uganda, United Kingdom, USA, Uruguay 1/03 CVVM “Would you support a war against Iraq?” Czech Republic (Figures represent percent responding “no”) 1/03 Gallup “Would you personally agree with or oppose Hungary a US military attack on Iraq without UN approval?” (Figures represent percent responding “oppose”) 2 1/03 EOS-Gallup “For each of the following propositions tell Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, me if you agree or not. -

Summer 2008 • Published at Vittoria, Ontario (519) 426-0234

750,000 Birds Banded 13 June Callwood Award 3-4 Alec Godden - a V&DF Hero 6-7 Long Point Biosphere 10 SOME Awesome Kids Awards 11-12 Lorraine Fletcher 8-9 Clara Bingleman 13-14 Magnificent Seven 20 OF THE Damn Dam! 14-15 One More ‘Minor’ decision! 18 Fantastic Year for Vittoria 3 Ontario Volunteer Service Awards 5 Farm Credit Corporation AgriSpirit Fund 5-6 St. Michael’s Champs 12-13 STUFF Gravy on Your Fries? 16-17 Sweet Corn Central 15-16 Innovative Farmers 12 Contributors + Volunteers = ‘Magic’ 2-3 INSIDE Jeanne Harding 9-10 Vic Gibbons 7-8 NO. 23 – SUMMER 2008 • PUBLISHED AT VITTORIA, ONTARIO (519) 426-0234 The Vittoria Booster The Vittoria Booster Newsletter is published twice a year by The Vittoria & District Foundation for its Members and Supporters. website: http://www.vittoria.on.ca e-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] A nn before a person’s name indicates that he or she is a member of The Vittoria & District Foundation. Milestone Anniversaries Celebrated Shirley and Ray Howick, 50 years on March 29 In Memoriam nnGinger and nnLarry Stanley, 45 years on April 6 Marjorie and Sam Kozak, 55 years on May 9 nn nn Robert Daniel “Bob” Benz, æ 58, on December 25 Ruth and Doug Gundry, 50 years on June 7 nn nnPhyllis and nnWilly Pollet, 45 years on June 7 Florence (Curry) Stephens, æ 91 on December 29 nn nn Marion Alice (Duxbury) Matthews, on December 29 Virginia and Tom Drayson, 50 years on June 28 Shelly Lillian Eaker, æ 73 on January 1 Harvey Aspden, æ 79 on January 1 ANNIVERSARIES OVER 60 CLUB Cecil Orval Carpenter, æ 53 on -

The Impact of ABC Canada's LEARN Campaign. Results of a National Research Study

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 405 472 CE 073 669 AUTHOR Long, Ellen TITLE The Impact of ABC Canada's LEARN Campaign. Results of a National Research Study. INSTITUTION ABC Canada, Toronto (Ontario). SPONS AGENCY National Literacy Secretariat, Ottawa (Ontario). PUB DATE Jul 96 NOTE 99p. PUB TYPE Reports Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Basic Education; *Adult Literacy; Adult Programs; *Advertising; Foreign Countries; High School Equivalency Programs; *Literacy Education; Marketing; *Program Effectiveness; *Publicity IDENTIFIERS *Canada; *Literacy Campaigns ABSTRACT An impact study was conducted of ABC CANADA's LEARN campaign, a national media effort aimed at linking potential literacy learners with literacy groups. Two questionnaires were administered to 94 literacy groups, with 3,557 respondents. Findings included the following:(1) 70 percent of calls to literacy groups were from adult learners aged 16-44;(2) more calls were received from men in rural areas and from women in urban areas; (3) 77 percent of callers were native English speakers;(4) 80 percent of callers had not completed high school, compared with 38 percent of the general population; (5) about equal numbers of learners were seeking elementary-level literacy classes and high-school level classes;(6) 44 percent of all calls to literacy organizations were associated with the LEARN campaign; and (7) 95 percent of potential learners who saw a LEARN advertisement said it helped them decide to call. The study showed conclusively that the LEARN campaign is having a profound impact on potential literacy learners and on literacy groups in every part of Canada. (This report includes 5 tables and 24 figures; 9 appendixes include detailed information on the LEARN campaign, the participating organizations, the surveys, and the impacts on various groups.) (KC) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document.