Copyright by Patrick Forsythe Shaw 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VBA Bulletin September 2019

Victorian Bridge Association Bulletin September 2019 Editor: Dee Harley TEAMS OF THREE All the players were winners as far as I am concerned, but the results were: The Teams of three conducted by Laura Under 25 MP Ginnan with the help of Damon was an immensely enjoyable occasion. 1. Ben Thomson with Alison Wright, Arthur Baigel and Tina Theodore 2. Christopher Leach and Peter Bolling with Barbara Cummings, and Liam Cochrane 3. Penny Corrigan with Sheldon Lipschitz, Robert Baker, Chris Butler Under 300 MP 1. Michael Phillips with Graham Forbes, Seb Wright, John Mai 2. Kim Frazer with David Hollands, Elizabeth Byrnes, Robert Jacobs 3. George Lovrecz with Dan Craine, Judy Leiba, Robyn Lichter TBIB SPONSORSHIP CHRISTOPHER LEACH I am delighted to advise that TBIB are resuming their sponsorship of the VBA in an expanded format over the summer/autumn [Damon] period. There were two sections: The VBA Council has approved the utilization of TBIB promotional and advertising material on both the VBA website and in the VBA The Under 25 Masterpoint: 8 teams Bulletin, commencing from now until the VCC next June. Under 300 Masterpoints: 12 teams. Details of the 2019/2020 TBIB Competition Teams comprised of a designated expert will appear in the October edition of VBA News (occasionally two) and three people deemed ready to improve. The expert played a session You can see the first article offered by TBIB with each of the other team members. At my on Page 6. table, we discussed the meaning of every bid, and the options which were available to the next bidder, this was generally seen to be very helpful. -

Poland Ukraine Fanguide Euro2012 CONTENTS Fanguide 2012 - Contents

Poland Ukraine Fanguide euro2012 CONTENTS Fanguide 2012 - Contents Contents 03 04 Foreword FSE/UEFA Welcome to Poland/Ukraine 06 Poland A-Z 08 Group A - Warsaw 14 Group A - Wrocław 16 Group A - Competing Countries 18 Group C - Gdańsk 22 Group C - Poznań 24 Group C - Competing Countries 26 Contents 30 Safety and Security 03 Match Schedule 32 34 Ukraine A-Z 40 Group B - Lviv 42 Group B - Kharkiv 44 Group B - Competing Countries 48 Group D - Kiev 50 Group D - Donetsk 52 Group D - Competing Countries Information for disabled fans 56 58 Words and Phrases - Ukraine Words and Phrases - Poland 60 62 Respect fansembassy.org // 2012fanguide.org // facebook.com/FansEmbassies // Twitter @FansEmbassies Foreword from FSE FSE Foreword from UEFA UEFA More than just a tourist guide… The thinking behind what we do is simple: supporters are the heart of football. If Welcome to Poland and Ukraine; These initiatives offer knowledge and insights Dear football supporters from all over you view fans coming to a tournament welcome to UEFA EURO 2012 from those who know best – your fellow Europe, Welcome to Euro 2012, as guests to be treated with respect and supporters. A key factor of the concept is Foreword from FSE and welcome to Poland and Ukraine! not as a security risk to be handled by “The supporters are the lifeblood of the production of fan guides with practical Foreword from UEFA police forces, they will behave accordingly. football“– that belief has formed UEFA’s information in different languages but, 04 What you are holding in your hands right They will enjoy themselves, party attitude towards football fans throughout most importantly, written in our common 05 now is the Football Supporters Europe (FSE) together and create a great atmosphere. -

Declarer Play Course – Fall 2014

DECLARER PLAY 2014 DECLARER TECHNIQUES Declarer Techniques are separate, identifiable techniques for Planning and Play of a hand of Duplicate Bridge as the Declarer. Each is extensively defined and illustrated in this section and, in most cases, also has detailed Problems and Answers for extra learning by analysis. Declarer Techniques throughout the book are marked with an asterisk, as they are often referred to in other Techniques descriptions, and other sections of the book or related documents. An example is Discovery*. This means there is a Declarer Technique named “Discovery”, and it will be found in this Section. Its exact page number can be found in the Table of Contents. Declarer Techniques Table of Contents – next page Auxiliary Play Terms. Following the Table of Contents is a page of auxiliary terms. They don’t necessarily represent Declarer Techniques per se, but are language worthy of explanation: they can be synonyms, bridge slang, etc. If you come across a term in the reading that you don’t understand, look first in the Declarer Techniques, then in the Auxiliary Terms for a possible synonym. Pg. 1 ©Bob McConnell, 2014 Declarer Techniques DECLARER PLAY 2014 DECLARER TECHNIQUES Technique Page Advanced Play Planning – Multiple Choices – Advanced Split Odds 4 Blind Spot Avoidance 8 Break a New Suit 10 Blocking opponents play 12 Unblocking 14 Card Combinations (Also in “Basic Section”) 16 Counting 23 Cross Ruff 26 Dangerous Opponent (in Basic Section Only) - Dummy Reversal 31 Deception 34 Discovery -

Chicago NABC Is Proud to Present One of Chicago’S Goodwill Day Premier Party Bands, Michael Lerich & His Orches- 9 A.M

July 23-August 2, 1998 70th Summer North American Bridge Championships Chicago Vol. 70, No. 4 Monday, July 27, 1998 Editors: Henry Francis and Paul Linxwiler DAILYAlden Senior sets Today isBULLETIN unbeatableAlden Seniorrecord of Chicago is married and he’s headed for grad school at the University Goodwill Day of Chicago. Since he and his wife are planning on having children soon, playing bridge Drink to your good may soon become just a memory for a few years. So Winners: Geoff Hampson and Eric Greco he’s trying to play all he can at health and good this tournament -- he calls it his swansong in tournament bridge. When he says he’s playing all he can, he means bridge Greco, Hampson win it. Yesterday he competed in FIVE sessions -- about 15 hours of pure bridge play. He took part in the morning game, the two-session Fast Pairs, the evening BoostedLife by Master a huge score in thePairs first session of side game and the midnight teams. Grand National Teams the final, Eric Greco and Geoff Hampson held on to “That’s a record that can never be beaten,” said narrowly win the Life Master Pairs. Their score of Alden. “If you can’t have quality, you need quantity.” 1726.88 was just enough to keep them ahead of the In the morning game, Alden had a section sec- victory makes Itabashi second-place father-son pair of Richard and Rich ond for .97 points. His seventh-place finish in the Fast Pavlicek who turned in a final score of 1726.03. -

Sommario Numero 3/4 Marzo/Aprile 2012

BBridridggeed’d’IItaliatalia Sommario numero 3/4 Marzo/Aprile 2012 Rivista bimestrale della Federazione Italiana Lettere al Bd’Irettore Marco Catellani 2 Gioco Bridge Via Giorgio Washington, 33 Campionato Italiano a coppie Miste Franco Broccoli 7 20146 Milano Tel. +39 02 70.000.333 r.a. Coppa Italia Men & Women Alberto Benetti 10 Fax +39 02 70.001.398 http://www.federbridge.it e-mail: [email protected] Coppa Italia di Categoria Franco Broccoli 16 Abbonamento annuo € 70 Il “Città di Milano” Franco Broccoli 20 Abbonamento tesserati FIGB € 50 La coppa Reisinger Alberto Benetti 22 Direttore Editoriale: – Marcello Marchioni World Mind Games Maurizio Di Sacco 24 Direttore: – Marco Catellani Passo a passo Pietro Forquet 28 Direttore Responsabile: – Valerio Giubilo Cattura della Donna Giampiero Bettinetti 34 Caporedattore: – Franco Broccoli Dichiariamo in Quinta Italiana Rodolfo Cerreto 36 Direzione e redazione: Bridge d’Italia c/o FIGB Kat for the Defence Marco Catellani 39 e-mail Bridge d’Italia: [email protected] Quinta Italiana Versione 2012 Causa, Gavelli, Rossi 40 Progetto grafico 41 e videoimpaginazione: Un’APP ci seppellirà Bruno Coen Sacerdotti – Romano Pacchiarini Tel. 349 47 72 857 Appelli Famosi Maurizio Di Sacco 42 e-mail: [email protected] Stampa: Al tavolo con Larry Larry Cohen 44 Tap Grafiche s.p.a. Via San Gimignano Belle figure Eddie Kantar 46 53036 Poggibonsi (SI) Tel. 0577 93 61 34 Tasselli licitativi G.Antonio Castiglioni 50 Fax 0577 93 63 90 Autorizzazione del Tribunale Così fu se vi pare Luca Marietti 52 di Milano N. 2939 del 7 gennaio 1953 Giocate (male) queste mani con me Mark Horton 54 N. -

Welcome to the 2012 APBF Bridge Congress

Sunday, August 25, 2012 Editors: Rich Colker, Barry Rigal Bulletin Number 1 Welcome to the 2012 APBF Bridge Congress Welcome to the 2012 APBF Congress, held this year at the beautiful Fukuoka Hilton Sea Hawk Hotel. There is something here for everyone: APBF Championship pair and team events in the Open, Women, Senior and Youth categories as well as pair and team side events for experienced or newer players. Hand records will be provided for the deals played in all events, and the Championship events will be covered live on BBO (see below). So may the force be with you — good fortune to all. The Main APBF and Daily Bulletin Offices and Directors We need your help to keep everyone informed of the exciting happenings at this congress. Please let us know about anything amusing, challenging, or skillful that happens at your table (bridge or otherwise). You can find us (most times) in the Daily Bulletin Office/Editor Room, located in the Nire Room near the playing area. If we’re not in, leave a note on the table next to one of our computers (they’re the two computers on the row of tables against the wall to the left as you enter). For most other questions or problems the APBF Office, located in the Kusu Room across from the Nire Room is the place to go. The APBF Office will be open each day at 9:00 am. You can contact us via house phone from the hotel or dial 092-822-2067 from outside the hotel. You may also contact the bulletin editors via e-mail at [email protected] or [email protected]. -

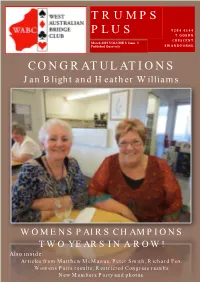

Trumps Plus Congratulations

TRUMPS PLUS 9 2 8 4 4 1 4 4 7 O D E R N C R E S C E N T March 2015 VOLUME 8 Issue 1 Published Quarterly SWANBOURNE CONGRATULATIONS Jan Blight and Heather Williams WOMENS PAIRS CHAMPIONS TWO YEARS IN A ROW! Also inside: Articles from Matthew McManus, Peter Smith, Richard Fox. Womens Pairs results; Restricted Congress results New Members Party and photos. CONTENTS Editorial You may have no- BRIDGE ARTICLES ticed that editions To Alert or Not To Alert Part 2 6 of Trumps Plus Matthew McManus have seasonal vari- Bidding 5 of a Major—What’s the 10 ations. Your edito- point? rial team certainly Peter Smith has. The March edition, for exam- Card Plays from Canberra 20 ple, reflects a thin Richard Fox season in the When the President Dropped by. 24 bridge world, that Richard Fox of late summer. Bit like the famers I guess – late summer early autumn is a lean season for both of us. Nonethe- EVENTS less there have been a few competi- tions at the Club that we report on Womens Pairs Championship 12 herein, including the Women’s Pairs. This is perhaps the premier competi- tion at the Club and Heather and Jan Restricted Swiss Pairs Congress 14 were back to back winners for 2014 and 2015. Well done Heather and Jan, and in particular well done Jan, New Members Party 16 who has three wins and a third over the past five years. At such a time we note once again the CLUB NEWS AND REGULAR moribund state of the Men’s Pairs. -

Choice of Entertaining Current Features of Interest to the Home Circle STAR

Page E SYRACUSE HERALD {Wednesday, June 5,' 1035. Choice of Entertaining Current Features of Interest to the Home Circle Men Make Mistake When They N\i II FURRY FAMILY'S CIRCUS -By Many W. Frew 1 1C i II O i C40 Refuse to Discuss Business - By Edgar Rice Burroughs - With Wives, Dorothy Dix Avers do'.vn. I ran m that direction. A CHAPTER XXIV rold-.er leaped !n front of n*.f. I hcsrd On this day tlie S?!d:crs of Lib- th? hi'-" o! the de.ith rays thst must Husbands Who Protect Mates in Life Often Leave have p.xsse\i c!o><* to my body, as h? lest period, -\r.d, my inln't bcir-.^ tlef- iried to .-:op ir.e. He must have beer, cither r.tTious or a very poor fehot, Them to Ruthless Sharpers in Their lor tie mlwed me. I turned my own tion. I piwcd tr:.e word around that wvapon upon him and pro.swd the Widowhood H'e would strike dur'.v.g thi- afternoon lever The man flumped to the deck «t the- moment the trr.r.-.neter s r.:::ded with ft hole In his chest, and I ran BY DOROTHY Dix the eleventh hour. As nui:y c* u* rpHE bitter complain or many wires Is that their husbands never tell them £5 were \vorici::c nl: near t'.ic a::nory The f.;ht at the door of the armory ~ anything about their buster* affairs. They do not knov how much wore to make a dt:h for it -*lth was har.d to har.d with swords and Kiron, who wju'.d ur.'-.xV: It in the fisu. -

2011 Thornhill Regional Bridge Tournament

Daily Bulletin 2011 Thornhill Regional Bridge Tournament Le Parc Banquet Hall, Thornhill, Ontario Tuesday, September 13, 2011 Welcome to the 2011 Thornhill Regional! NAP Unit Qualification The next round of NAP qualification is about to begin. The Unit 246 finals for all levels will be held on Saturday October 22nd in Ajax at the St. Andrews Seniors Center. Cost per player is a total of $25 for both sessions if you preregister by October 19th which includes a light lunch between sessions. To preregister please contact Irfan Ashraf ([email protected]) or Ian Coats ([email protected]), for more details please visit the Unit website at www.unit246.com. Monday Afternoon 1st N/S in 299er pairs Bonnie Gluck and Heather Kagan Unit 246 Special Events Coordinator Irfan Ashraf The Unit 166 finals will be held on three separate dates (one for each flight) in three locations. Section tops in Flight C in Monday Afternoon Please visit the Unit 166 website 299er pairs, Ruth Falkenstein and Marion Joffe (www.unit166.ca) for further details. SCHEDULE Sunday, Sept 11 Stratiflighted Swiss Teams 11 am & TBD 0 – 299er Swiss Teams 11 am & TBD Monday, Sept. 12 2 Day Early Morning Bracketed Compact KO I finishes Tuesday morning 9 am Morning Side Game Series* 5 sessions Mon. – Fri 9 am Stratiflighted Pairs – (A/X & B/C/D) two sessions 1 & 7 pm Monday & Tuesday Bracketed KO sessions 1 & 2 1 & 7 pm Intermediate/Novice Games 1 & 7 pm Afternoon Side Game Series* 5 sessions Mon. – Fri 1 pm Evening Side Game Series* 5 sessions Mon. -

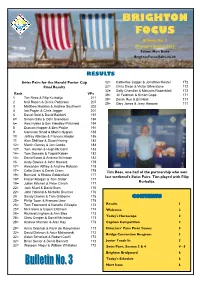

BRIGHTON FOCUS Bulletin No

BRIGHTON FOCUS Bulletin No. 3 Monday 9 August 2010 Editor: Matt Betts [email protected] RESULTS Swiss Pairs for the Harold Poster Cup 32= Catherine Jagger & Jonathan Mestel 172 Final Results 32= Chris Dixon & Victor Silverstone 172 32= Sally Chandler & Malcolm Rosenblatt 172 Rank VPs 39= Jill Feldman & Simon Cope 171 1 Tim Rees & Filip Kurbalija 211 39= Derek Rue & Bill Hirst 171 2 Neil Rosen & Derek Patterson 207 39= Gary Jones & Jerry Harouni 171 3 Matthew Hoskins & Andrew Southwell 202 4 Ian Pagan & Chris Jagger 201 5 David Gold & David Bakhshi 197 6= Simon Gillis & Odin Svendsen 194 6= Alex Hydes & Ben Handley-Pritchard 194 8 Duncan Happer & Ben Paske 191 9 Cameron Small & Martin Nygren 188 10 Jeffrey Allerton & Frances Hinden 186 11 Alan Shillitoe & Stuart Haring 184 12= Martin Garvey & Jon Cooke 183 12= Tom Hanlon & Hugh McGann 183 14= Tom Dessain & Tugrul Kaban 182 14= David Ewart & Andrew McIntosh 182 16 Andy Bowles & John Howard 179 17= Alexander Allfrey & Andrew Robson 178 17= Celia Oram & Derek Oram 178 Tim Rees, one half of the partnership who won 19= Bernard & Rhona Goldenfield 177 last weekend’s Swiss Pairs. Tim played with Filip 19= Frazer Morgan & Tom Slater 177 Kurbalija. 19= Julian Mitchell & Peter Clinch 177 22= Jack Mizel & David Burn 176 22= John Holland & Michelle Brunner 176 24 Sandy Davies & Tom Gisborne 175 CONTENTS 25= Philip Town & Frances Liew 174 25= Tom Townsend & Nanette Gillespie 174 Results 1 25= Nick Irens & Espen Erichsen 174 Welcome 2 28= Richard Lingham & Ann Slee 173 Today’s Horoscope 2 28= Chris Cooper & Daniel McIntosh 173 28= Andrew Macnair & Alan Kay 173 Caption Competition 2 28= Anna Onishuk & Karel de Raeymaker 173 Directors’ Pairs Pivot Teams 3 32= David Dickson & Artur Malinowski 172 Bridge Convention Anagram 3 32= Aidan Schofield & Robert Covill 172 32= Brian Senior & Denis Bennett 172 Junior Teach-In 3 32= Waseem Naqvi & William Whittaker 172 Swiss Pairs, Session 3 & 4 4 - 5 Brighton Bridgword 6 Today’s Schedule 6 Next Issue 6 Bulletin No. -

The Improbable Heart Game…And How It Becomes Possible! ♦ ♣

♠ ♥ The Improbable Heart Game…and How It Becomes Possible! ♦ ♣ On Thursday, 19th October 2017, Board #12 proved challenging for defenders and declarers. The printed hand records suggest that ten tricks can be made yet only five of fourteen declarers managed that feat! And, in truth I am not surprised. Why? Because upon first look it is not clear how to make ten tricks. Declarer can count five trump tricks, one top spade and two top diamonds. But, that brings the total to only eight tricks. Yes, an extra trick can be created in spades BUT that still leaves declarer with two losing clubs and two losing spades. So, how can ten tricks LEGITIMATELY be manufactured by declarer? First of all I will venture some possible explanations as to how ten tricks were made at some tables. 1) In all cases North was declarer and the obvious lead is the ♣K. How the defense proceeds after that hinges on what West does at trick one and / or trick two and then what East or West does at trick three. Best is for West to overtake at trick one with ♣A and return a club to East’s ♣Q after North follows suit. It’s at this point that I would venture a bet that some East’s fell from grace by leading ♣10 at trick three. Declarer will ruff, draw trumps and then subsequently cash the ♣9, which by now, has been established as a winner! This can be avoided if East leads a small club, which West can ruff and North will over-ruff …BUT East will still hold the master club (♣10) and dummy will have the singleton ♣9 which is NOT a winner! 2) An alternative explanation as to how the contract might have succeeded could be that East switched to a diamond after winning the second trick with ♣Q. -

Squeeze Refresher

SQUEEZE REFRESHER For Good Bridge Players By Marvin L. French CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..........................................................1 NOMENCLATURE.........................................................2 Threat Types.........................................................2 Additional Definitions ..................................................3 Notes...............................................................3 RULES FOR ALL SQUEEZES ................................................4 Declarer: ............................................................4 Defenders:...........................................................4 SIMPLE SQUEEZES........................................................5 Sinister Squeeze .......................................................5 Ambidextrous Squeeze ..................................................6 Splitter Squeeze .......................................................7 Back-Door Squeeze ....................................................8 Criss-Cross Squeeze ...................................................9 Defender’s Winner Squeezes Partner .......................................9 Defenders Squeeze Declarer ..............................................9 Declarer Squeezes Self ..................................................9 TRUMP SQUEEZES .......................................................10 Trump.............................................................10 Scissors............................................................12 TWO-SUIT STRIP SQUEEZES...............................................14