The Ofra Settlement – an Unauthorized Outpost

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

At the Supreme Court Sitting As the High Court of Justice

Disclaimer: The following is a non-binding translation of the original Hebrew document. It is provided by HaMoked: Center for the Defence of the Individual for information purposes only. The original Hebrew prevails in any case of discrepancy. While every effort has been made to ensure its accuracy, HaMoked is not liable for the proper and complete translation nor does it accept any liability for the use of, reliance on, or for any errors or misunderstandings that may derive from the English translation. For queries about the translation please contact [email protected] At the Supreme Court HCJ 5839/15 Sitting as the High Court of Justice HCJ 5844/15 1. _________ Sidr 2. _________ Tamimi 3. _________ Al Atrash 4. _________ Tamimi 5. _________ A-Qanibi 6. _________ Taha 7. _________ Al Atrash 8. _________ Taha 9. HaMoked: Center for the Defence of the Individual, founded by Dr. Lotte Salzberger - RA Represented by counsel, Adv. Andre Rosenthal 15 Salah a-Din St., Jerusalem Tel: 6250458, Fax: 6221148; cellular: 050-5910847 The Petitioners in HCJ 5839/15 1. Anonymous 2. Anonymous 3. Anonymous 4. HaMoked: Center for the Defence of the Individual, founded by Dr. Lotte Salzberger – RA Represented by counsel, Adv. Michal Pomeranz et al. 10 Huberman St. Tel Aviv-Jaffa 6407509 Tel: 03-5619666; Fax: 03-6868594 The Petitioners in HCJ 5844/15 v. Military Commander of the West Bank Area Represented by the State Attorney's Office Ministry of Justice, Jerusalem Tel: 02-6466008; Fax: 02-6467011 The Respondent in HCJ 5839/15 1. Military Commander of the West Bank Area 2. -

Box Folder 16 7 Association of Americans and Canadians in Israel

MS-763: Rabbi Herbert A. Friedman Collection, 1930-2004. Series F: Life in Israel, 1956-1983. Box Folder 16 7 Association of Americans and Canadians in Israel. War bond campaign. 1973-1977. For more information on this collection, please see the finding aid on the American Jewish Archives website. 3101 Clifton Ave, Cincinnati, Ohio 45220 513.487.3000 AmericanJewishArchives.org 'iN-,~":::I n,JT11 n11"~r.IN .. •·nu n1,nNnn ASSOCIATION OF AMERICANS & CANADIANS IN 151tAn AACI is tbe representative oftbt America•"'"' Ca114tlian ZU>nisJ FednatU>ns for olim nd tmJ/llfllory 1Tsit/nti ill lnwl. Dr. Hara.n P~reNe Founding Pruldet1t Or. Israel Goldste~n Honorary Pres I detrt David 8resl11.1 Honorary Vice Pres. "1a rch 9, 1977 MATIDHAL OFFICERS Yltzhak K.f.,.gwltz ~abbi Her bert Friedman, President llerko De¥Or 15 ibn Gvirol St., Vlca P'resldent Jerusalem. G•rshon Gross Vice P're~ldeftt Ell~Yanow Trus-•r: o- Ede lste In Secretuy SI .. Altlllan Dear Her b, •-· P'Ht Pr.esldeftt "ECilO!W. CH'-IMEM lla;;ocJI ta;lerlnsky I wonder if I can call upon you to do something special Beersheva for the Emergency Fund Drive wh ich \-le ar e conducting. Arie Fr- You kno\-1 a 11 the Reform Rabbis from the United States Hllf1 · "1va Fr..0-n and Canada who are in Israel. Could you send a letter Jerusa.1- to each of them asking that they contribute to the 0pld Dow Ne tanya drive? 119f'ry "...._r Meta,.,.a I kno\-J that most of them will not contribute IL 1,000, Stefe11le Bernstein Tai AYlv but even sma ller contributions are we lcome at this time. -

Israel's National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict

Leap of Faith: Israel’s National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict Middle East Report N°147 | 21 November 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iv I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Religious Zionism: From Ascendance to Fragmentation ................................................ 5 A. 1973: A Turning Point ................................................................................................ 5 B. 1980s and 1990s: Polarisation ................................................................................... 7 C. The Gaza Disengagement and its Aftermath ............................................................. 11 III. Settling the Land .............................................................................................................. 14 A. Bargaining with the State: The Kookists ................................................................... 15 B. Defying the State: The Hilltop Youth ........................................................................ 17 IV. From the Hills to the State .............................................................................................. -

OBITUARIES Picked up at a Comer in New York City

SUMMER 2004 - THE AVI NEWSLETTER OBITUARIES picked up at a comer in New York City. gev until his jeep was blown up on a land He was then taken to a camp in upper New mine and his injuries forced him to return York State for training. home one week before the final truce. He returned with a personal letter nom Lou After the training, he sailed to Harris to Teddy Kollek commending him Marseilles and was put into a DP camp on his service. and told to pretend to be mute-since he spoke no language other than English. Back in Brooklyn Al worked While there he helped equip the Italian several jobs until he decided to move to fishing boat that was to take them to Is- Texas in 1953. Before going there he took rael. They left in the dead of night from Le time for a vacation in Miami Beach. This Havre with 150 DPs and a small crew. The latter decision was to determine the rest of passengers were carried on shelves, just his life. It was in Miami Beach that he met as we many years later saw reproduced in his wife--to-be, Betty. After a whirlwind the Museum of Clandestine Immigration courtship they were married and decided in Haifa. Al was the cook. On the way out to raise their family in Miami. He went the boat hit something that caused a hole into the uniform rental business, eventu- Al Wank, in the ship which necessitated bailing wa- ally owning his own business, BonMark Israel Navy and Palmach ter the entire trip. -

Arrested Development: the Long Term Impact of Israel's Separation Barrier in the West Bank

B’TSELEM - The Israeli Information Center for ARRESTED DEVELOPMENT Human Rights in the Occupied Territories 8 Hata’asiya St., Talpiot P.O. Box 53132 Jerusalem 91531 The Long Term Impact of Israel's Separation Tel. (972) 2-6735599 | Fax (972) 2-6749111 Barrier in the West Bank www.btselem.org | [email protected] October 2012 Arrested Development: The Long Term Impact of Israel's Separation Barrier in the West Bank October 2012 Research and writing Eyal Hareuveni Editing Yael Stein Data coordination 'Abd al-Karim Sa'adi, Iyad Hadad, Atef Abu a-Rub, Salma a-Deb’i, ‘Amer ‘Aruri & Kareem Jubran Translation Deb Reich Processing geographical data Shai Efrati Cover Abandoned buildings near the barrier in the town of Bir Nabala, 24 September 2012. Photo Anne Paq, activestills.org B’Tselem would like to thank Jann Böddeling for his help in gathering material and analyzing the economic impact of the Separation Barrier; Nir Shalev and Alon Cohen- Lifshitz from Bimkom; Stefan Ziegler and Nicole Harari from UNRWA; and B’Tselem Reports Committee member Prof. Oren Yiftachel. ISBN 978-965-7613-00-9 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................ 5 Part I The Barrier – A Temporary Security Measure? ................. 7 Part II Data ....................................................................... 13 Maps and Photographs ............................................................... 17 Part III The “Seam Zone” and the Permit Regime ..................... 25 Part IV Case Studies ............................................................ 43 Part V Violations of Palestinians’ Human Rights due to the Separation Barrier ..................................................... 63 Conclusions................................................................................ 69 Appendix A List of settlements, unauthorized outposts and industrial parks on the “Israeli” side of the Separation Barrier .................. 71 Appendix B Response from Israel's Ministry of Justice ....................... -

The Economic Base of Israel's Colonial Settlements in the West Bank

Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute The Economic Base of Israel’s Colonial Settlements in the West Bank Nu’man Kanafani Ziad Ghaith 2012 The Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS) Founded in Jerusalem in 1994 as an independent, non-profit institution to contribute to the policy-making process by conducting economic and social policy research. MAS is governed by a Board of Trustees consisting of prominent academics, businessmen and distinguished personalities from Palestine and the Arab Countries. Mission MAS is dedicated to producing sound and innovative policy research, relevant to economic and social development in Palestine, with the aim of assisting policy-makers and fostering public participation in the formulation of economic and social policies. Strategic Objectives Promoting knowledge-based policy formulation by conducting economic and social policy research in accordance with the expressed priorities and needs of decision-makers. Evaluating economic and social policies and their impact at different levels for correction and review of existing policies. Providing a forum for free, open and democratic public debate among all stakeholders on the socio-economic policy-making process. Disseminating up-to-date socio-economic information and research results. Providing technical support and expert advice to PNA bodies, the private sector, and NGOs to enhance their engagement and participation in policy formulation. Strengthening economic and social policy research capabilities and resources in Palestine. Board of Trustees Ghania Malhees (Chairman), Ghassan Khatib (Treasurer), Luay Shabaneh (Secretary), Mohammad Mustafa, Nabeel Kassis, Radwan Shaban, Raja Khalidi, Rami Hamdallah, Sabri Saidam, Samir Huleileh, Samir Abdullah (Director General). Copyright © 2012 Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS) P.O. -

Secretariats of Roads Transportation Report 2015

Road Transportation Report: 2015. Category Transfer Fees Amount Owed To lacal Remained No. Local Authority Spent Amount Clearing Amount classification 50% Authorities 50% amount 1 Albireh Don’t Exist Municipality 1,158,009.14 1,158,009.14 0.00 1,158,009.14 2 Alzaytouneh Don’t Exist Municipality 187,634.51 187,634.51 0.00 187,634.51 3 Altaybeh Don’t Exist Municipality 66,840.07 66,840.07 0.00 66,840.07 4 Almazra'a Alsharqia Don’t Exist Municipality 136,262.16 136,262.16 0.00 136,262.16 5 Banizeid Alsharqia Don’t Exist Municipality 154,092.68 154,092.68 0.00 154,092.68 6 Beitunia Don’t Exist Municipality 599,027.36 599,027.36 0.00 599,027.36 7 Birzeit Don’t Exist Municipality 137,285.22 137,285.22 0.00 137,285.22 8 Tormos'aya Don’t Exist Municipality 113,243.26 113,243.26 0.00 113,243.26 9 Der Dibwan Don’t Exist Municipality 159,207.99 159,207.99 0.00 159,207.99 10 Ramallah Don’t Exist Municipality 832,407.37 832,407.37 0.00 832,407.37 11 Silwad Don’t Exist Municipality 197,183.09 197,183.09 0.00 197,183.09 12 Sinjl Don’t Exist Municipality 158,720.82 158,720.82 0.00 158,720.82 13 Abwein Don’t Exist Municipality 94,535.83 94,535.83 0.00 94,535.83 14 Atara Don’t Exist Municipality 68,813.12 68,813.12 0.00 68,813.12 15 Rawabi Don’t Exist Municipality 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 16 Surda - Abu Qash Don’t Exist Municipality 73,806.64 73,806.64 0.00 73,806.64 17 Hay Alkarama Don’t Exist Village Council 7,551.17 7,551.17 0.00 7,551.17 18 Almoghayar Don’t Exist Village Council 71,784.87 71,784.87 0.00 71,784.87 19 Alnabi Saleh Don’t Exist Village Council -

Peace Between Israel and the Palestinians Appears to Be As Elusive As Ever. Following the Most Recent Collapse of American-Broke

38 REVIVING THE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN PEACE PROCESS: HISTORICAL LES- SONS FOR THE MARCH 2015 ISRAELI ELECTIONS Elijah Jatovsky Lessons derived from the successes that led to the signing of the 1993 Declaration of Principles between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization highlight modern criteria by which a debilitated Israeli-Palestinian peace process can be revitalized. Writ- ten in the run-up to the March 2015 Israeli elections, this article examines a scenario for the emergence of a security-credentialed leadership of the Israeli Center-Left. Such leadership did not in fact emerge in this election cycle. However, should this occur in the future, this paper proposes a Plan A, whereby Israel submits a generous two-state deal to the Palestinians based roughly on that of Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert’s offer in 2008. Should Palestinians find this offer unacceptable whether due to reservations on borders, Jerusalem or refugees, this paper proposes a Plan B by which Israel would conduct a staged, unilateral withdrawal from large areas of the West Bank to preserve the viability of a two-state solution. INTRODUCTION Peace between Israel and the Palestinians appears to be as elusive as ever. Following the most recent collapse of American-brokered negotiations in April 2014, Palestinians announced they would revert to pursuing statehood through the United Nations (UN), a move Israel vehemently opposes. A UN Security Council (UNSC) vote on some form of a proposal calling for an end to “Israeli occupation in the West Bank” by 2016 is expected later this month.1 In July 2014, a two-month war between Hamas-controlled Gaza and Israel broke out, claiming the lives of over 2,100 Gazans (this number encompassing both combatants and civilians), 66 Israeli soldiers and seven Israeli civilians—the low number of Israeli civilians credited to Israel’s sophisti- cated anti-missile Iron Dome system. -

November 2014 Al-Malih Shaqed Kh

Salem Zabubah Ram-Onn Rummanah The West Bank Ta'nak Ga-Taybah Um al-Fahm Jalameh / Mqeibleh G Silat 'Arabunah Settlements and the Separation Barrier al-Harithiya al-Jalameh 'Anin a-Sa'aidah Bet She'an 'Arrana G 66 Deir Ghazala Faqqu'a Kh. Suruj 6 kh. Abu 'Anqar G Um a-Rihan al-Yamun ! Dahiyat Sabah Hinnanit al-Kheir Kh. 'Abdallah Dhaher Shahak I.Z Kfar Dan Mashru' Beit Qad Barghasha al-Yunis G November 2014 al-Malih Shaqed Kh. a-Sheikh al-'Araqah Barta'ah Sa'eed Tura / Dhaher al-Jamilat Um Qabub Turah al-Malih Beit Qad a-Sharqiyah Rehan al-Gharbiyah al-Hashimiyah Turah Arab al-Hamdun Kh. al-Muntar a-Sharqiyah Jenin a-Sharqiyah Nazlat a-Tarem Jalbun Kh. al-Muntar Kh. Mas'ud a-Sheikh Jenin R.C. A'ba al-Gharbiyah Um Dar Zeid Kafr Qud 'Wadi a-Dabi Deir Abu Da'if al-Khuljan Birqin Lebanon Dhaher G G Zabdah לבנון al-'Abed Zabdah/ QeiqisU Ya'bad G Akkabah Barta'ah/ Arab a-Suweitat The Rihan Kufeirit רמת Golan n 60 הגולן Heights Hadera Qaffin Kh. Sab'ein Um a-Tut n Imreihah Ya'bad/ a-Shuhada a a G e Mevo Dotan (Ganzour) n Maoz Zvi ! Jalqamus a Baka al-Gharbiyah r Hermesh Bir al-Basha al-Mutilla r e Mevo Dotan al-Mughayir e t GNazlat 'Isa Tannin i a-Nazlah G d Baqah al-Hafira e The a-Sharqiya Baka al-Gharbiyah/ a-Sharqiyah M n a-Nazlah Araba Nazlat ‘Isa Nazlat Qabatiya הגדה Westהמערבית e al-Wusta Kh. -

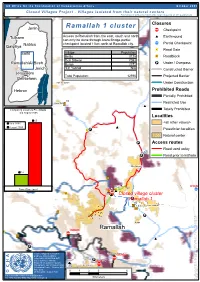

Ramallah 1 Cluster Closures Jenin ‚ Checkpoint

D UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs October 2005 º¹P Closed Villages Project - Villages isolated from their natural centers º¹P Palestinians without permits (the large majority of the population) /" ## Ramallah 1 cluster Closures Jenin ¬Ç Checkpoint ## Tulkarm AccessSalfit to Ramallah from the east, south and north Earthmound can only be done through Atara Bridge partial ¬Ç Nablus checkpoint located 11km north of Ramallah city. Partial Checkpoint Qalqiliya D Road## Gate Salfit Village Population Beitin 3125 /" Roadblock Deir Dibwan 7093 º¹ Ramallah/Al Bireh Burqa 2372 P Under / Overpass 'Ein Yabrud N/A ## Jericho ### Constructed Barrier Jerusalem Total Population: 12590 ## Projected Barrier Bethlehem ## Deir as Sudan Deir as Sudan ## Under Construction ## Hebron Prohibited Roads C /" An Nabi Salih Partially Prohibited ¬Ç ## 15 Umm Safa/" Restricted Use ## # # Comparing situations Pre-Intifada Totally Prohibited and August 2005 Localities 65 Year 2000 <all other values> August 2005 Atara ## D ¬Çº¹P Palestinian localities Natural center º¹P Access routes Road used today 11 12 ##º¹P/" Road prior to Intifada 'Ein'Ein YabrudYabrud 12 /" /" 10 At Tayba /" 9 Beitin Ç Travel Time (min) DCO 2 D ¬ /"Ç## /" ¬/"3 ## 1 Closed village cluster Ramallahº¹P 1 42 /" 43 Deir Dibwan /" /" º¹P the part of the the of part the Burqa Ramallah delimitation the concerning D ¬Ç Beituniya /" ## º¹DP Closure mapping is a work in Qalandiya QalandiyaCamp progress. Closure data is Ç collected by OCHA field staff º¹ ¬ Beit Duqqu and is subject to change. P Atarot 144 Maps will be updated regularly. ### ¬Ç Cartography: OCHA Humanitarian 170 Al Judeira Information Centre - October 2005 Al Jib Beit 'Anan ## Bir Nabala Base data: Al 036Jib 12 O C H A O C H OCHA updateBeit AugustIjza 2005 losedFor comments village contact <[email protected]> cluster # # Tel. -

Radicalization of the Settlers' Youth: Hebron As a Hub for Jewish Extremism

© 2014, Global Media Journal -- Canadian Edition Volume 7, Issue 1, pp. 69-85 ISSN: 1918-5901 (English) -- ISSN: 1918-591X (Français) Radicalization of the Settlers’ Youth: Hebron as a Hub for Jewish Extremism Geneviève Boucher Boudreau University of Ottawa, Canada Abstract: The city of Hebron has been a hub for radicalization and terrorism throughout the modern history of Israel. This paper examines the past trends of radicalization and terrorism in Hebron and explains why it is still a present and rising ideology within the Jewish communities and organization such as the Hilltop Youth movement. The research first presents the transmission of social memory through memorials and symbolism of the Hebron hills area and then presents the impact of Meir Kahana’s movement. As observed, Hebron slowly grew and spread its population and philosophy to the then new settlement of Kiryat Arba. An exceptionally strong ideology of an extreme form of Judaism grew out of those two small towns. As analyzed—based on an exhaustive ethnographic fieldwork and bibliographic research—this form of fundamentalism and national-religious point of view gave birth to a new uprising of violence and radicalism amongst the settler youth organizations such as the Hilltop Youth movement. Keywords: Judaism; Radicalization; Settlers; Terrorism; West Bank Geneviève Boucher Boudreau 70 Résumé: Dès le début de l’histoire moderne de l’État d’Israël, les villes d’Hébron et Kiryat Arba sont devenues une plaque tournante pour la radicalisation et le terrorisme en Cisjordanie. Cette recherche examine cette tendance, explique pourquoi elle est toujours d’actualité ainsi qu’à la hausse au sein de ces communautés juives. -

Deir Dibwan Town Profile

Deir Dibwan Town Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation 2012 Palestinian Localities Study Ramallah Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 1 Palestinian Localities Study Ramallah Governorate Background This report is part of a series of booklets, which contain compiled information about each city, town, and village in the Ramallah Governorate. These booklets came as a result of a comprehensive study of all localities in Ramallah Governorate, which aims at depicting the overall living conditions in the governorate and presenting developmental plans to assist in developing the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment;" the project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID). The "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the needed programs and activities to mitigate the impact of the current unsecure political, economic and social conditions in Ramallah Governorate. The project's objectives are to survey, analyze, and document the available natural, human, socioeconomic and environmental resources, and the existing limitations and needs assessment for the development of the rural and marginalized areas in Ramallah Governorate.