Indian Horizons Volume 63 No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ribbit Sweet Yarns for Real Life

Ribbit a free design by Susan B. Anderson ™ ™ www.spudandchloe.com ™ sweet yarns for real life Black embroidery floss Stitch marker Stitch holder or waste yarn Gauge: 6 stitches per inch in stockinette stitch Abbreviations: k: knit p: purl k2tog: knit 2 stitches together m1: make a stitch by placing the bar between the stitches on the left needle and knitting it through the back loop kfb: knit in the front and back of the same stitch st(s): stitch(es) rnd(s): round(s) Body: Starting at the bottom of the body with Grass and the double‐ pointed needles cast on 9 stitches placing 3 stitches on each of 3 double‐pointed needles. Join to work in the round being careful not to twist the stitches. Place a stitch marker on the first stitch. Rnd 1: knit Rnd 2: (k1, m1, k1, m1, k1) repeat to the end of the round (5 sts per needle, 15 sts total) Rnd 3: knit Rnd 4: (k1, m1, knit to the last stitch on the needle, m1, k1) repeat on each needle Rnd 5: knit Repeat rounds 4 and 5 until there are 15 stitches on each needle, Finished Measurements: 45 stitches total. 3 inches wide by 5 inches tall End with a round 4. Place a stitch marker on the last completed round and leave it there. Yarn: Knit every round until the body measures 1½ inches above the Spud & Chloë Sweater (55% superwash wool, 45 % organic stitch marker. cotton; 160 yards/100grams), 1 skein in Grass #7502 Decrease rounds: Tools: Rnd 1: (k3, k2tog) repeat to the end of the round (12 sts per US size 5 double pointed needles, set of 4 or size to obtain gauge needle, 36 sts total remain) Yarn needle Rnd 2: (k2, k2tog) repeat to the end of the round (9 sts per needle, Scissors 27 sts total remain) Tape measure or ruler Polyester fiber‐fill (small amount) Tennis ball (optional) © 2012 • This pattern is copyrighted material and under the copyright laws of the United States. -

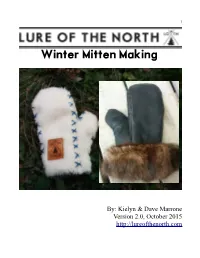

Winter Mitten Making

1 Winter Mitten Making By: Kielyn & Dave Marrone Version 2.0, October 2015 http://lureofthenorth.com 2 Note 1- This booklet is part of a series of DIY booklets published by Lure of the North. For all other publications in this series, please see our website at lureofthenorth.com. Published instructional booklets can be found under "Info Hub" in the main navigation menu. Note 2 – Lure Mitten Making Kits: These instructions are intended to be accompanied by our Mitten Making Kit, which is available through the “Store” section of our website at: http://lureofthenorth.com/shop. Of course, you can also gather all materials yourself and simply use these instructions as a guide, modifying to suit your requirements. Note 3 - Distribution: Feel free to distribute these instructions to anyone you please, with the requirement that this package be distributed in its entirety with no modifications whatsoever. These instructions are also not to be used for any commercial purpose. Thank you! Note 4 – Feedback and Further Help: Feedback is welcomed to improve clarity in future editions. For even more assistance you might consider taking a mitten making workshop with us. These workshops are run throughout Ontario, and include hands-on instructions and all materials. Go to lureofthenorth.com/calendar for an up to date schedule. Our Philosophy: This booklet describes our understanding of a traditional craft – these skills and this knowledge has traditionally been handed down from person to person and now we are attempting to do the same. We are happy to have the opportunity to share this knowledge with you, however, if you use these instructions and find them helpful, please give credit where it is due. -

From the Sun Region of the Embroiderers’ Guild of America, Inc

from The Sun Region of The Embroiderers’ Guild of America, Inc. website: www.sunregionega.org RD’s Letter Hello Sun Region, I hope that all of you are enjoying the cooler weather. I’m enjoying being outside more and working in the gar- den. Plus, it helps me get into the spirit of the season. Speaking of the season, yesterday was my chapter’s Christmas party. It was well attended but best of all, Audrey Francini was there. Most of you know, or know of, Audrey and her wonderful stitching. She’s an EGA icon. I talked to Audrey for a little bit and she said that she’s still stitching although she believes that it’s not as good as it used to be. We both agreed that without our stitch- ing we don’t know what we would do with ourselves. The big news for Audrey is that she has a big birthday com- ing up on December 22 . She will be 100! Please join me in wishing Audrey a very happy birthday and a wish for many more. The Florida State Fair is coming in February. Have you ever been? More importantly, have you ever entered something in the fair? If not, you should think about it. They have a fiber arts section that includes just about everything. I’ve been in touch with Brenda Gregory the coordinator of the family exhibits division. She’s trying to encourage more entries and would like some quality entries from EGA. The handbook is out and is very detailed in how to enter, etc. -

I D F Kaikrafts

+91-8048372333 I D F Kaikrafts https://www.indiamart.com/idf-kaikrafts/ Kai Krafts, a project of the Bangalore based NGO, Initiatives for Development Foundation (idf) supports artisans and crafts pertaining to North Karnataka. Through concentrated marketing efforts, Kai Krafts strives to revive North Karnataka crafts ... About Us Kai Krafts, a project of the Bangalore based NGO, Initiatives for Development Foundation (idf) supports artisans and crafts pertaining to North Karnataka. Through concentrated marketing efforts, Kai Krafts strives to revive North Karnataka crafts and to improve the earning potential of the skilled artisans versed in these crafts. Our name stems from the Kannada word for “hand” or “kai” and reflects our mission to promote handmade products from North Karnataka. As a project of the NGO, idf, we work closely with the artisans to fuse traditional crafts with products geared towards a contemporary market. Initially, our project was supported by Give2Asia. This fund was released by Give2Asia through the Deshpande Foundation, who monitored the programme throughout the funded period of April, 2010 to March 31, 2011. IDF Federation was the implementing agent and has been supervising the entire project to date. At Kai Krafts, we endeavor to provide customers with unique, handmade and ethical products. By linking artisan clusters with markets, Kai Krafts both ensures that the artisans are paid fair wages for their hard work and that these crafts endure. Kai Krafts is currently marketing the products of artisans skilled in the highly technical and difficult embroidery form of Kasuti. Kasuti is comprised of the Kannada words “Kai” meaning hand and “Suti” meaning cotton thread thus translating to “handwork of cotton thread.”.. -

Dress and Fabrics of the Mughals

Chapter IV Dress and Fabrics of the Mughals- The great Mughal emperor Akbar was not only a great ruler, an administrator and a lover of art and architecture but also a true admirer and entrepreneur of different patterns and designs of clothing. The changes and development brought by him from Ottoman origin to its Indian orientation based on the land‟s culture, custom and climatic conditions. This is apparent in the use of the fabric, the length of the dresses or their ornamentation. Since very little that is truly contemporary with the period of Babur and Humayun has survived in paintings, it is not easy to determine exactly what the various dresses look like other than what has been observed by the painters themselves. But we catch a glimpse of the foreign style of these dresses even in the paintings from Akbar‟s period which make references, as in illustrations of history or chronicles of the earlier times like the Babar-Namah or the Humayun-Namah.1 With the coming of Mughals in India we find the Iranian and Central Asian fashion in their dresses and a different concept in clothing.2 (Plate no. 1) Dress items of the Mughals: Akbar paid much attention to the establishment and working of the various karkhanas. Though articles were imported from Iran, Europe and Mongolia but effort were also made to produce various stuffs indigenously. Skilful master and workmen were invited and patronised to settle in this country to teach people and improve system of manufacture.2 Imperial workshops Karkhanas) were established in the towns of Lahore, Agra, Fatehpur Sikri and Ahmedabad. -

GI Journal No. 75 1 November 26, 2015

GI Journal No. 75 1 November 26, 2015 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS JOURNAL NO.75 NOVEMBER 26, 2015 / AGRAHAYANA 05, SAKA 1936 GI Journal No. 75 2 November 26, 2015 INDEX S. No. Particulars Page No. 1 Official Notices 4 2 New G.I Application Details 5 3 Public Notice 6 4 GI Applications Bagh Prints of Madhya Pradesh (Logo )- GI Application No.505 7 Sankheda Furniture (Logo) - GI Application No.507 19 Kutch Embroidery (Logo) - GI Application No.509 26 Karnataka Bronzeware (Logo) - GI Application No.510 35 Ganjifa Cards of Mysore (Logo) - GI Application No.511 43 Navalgund Durries (Logo) - GI Application No.512 49 Thanjavur Art Plate (Logo) - GI Application No.513 57 Swamimalai Bronze Icons (Logo) - GI Application No.514 66 Temple Jewellery of Nagercoil (Logo) - GI Application No.515 75 5 GI Authorised User Applications Patan Patola – GI Application No. 232 80 6 General Information 81 7 Registration Process 83 GI Journal No. 75 3 November 26, 2015 OFFICIAL NOTICES Sub: Notice is given under Rule 41(1) of Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration & Protection) Rules, 2002. 1. As per the requirement of Rule 41(1) it is informed that the issue of Journal 75 of the Geographical Indications Journal dated 26th November 2015 / Agrahayana 05th, Saka 1936 has been made available to the public from 26th November 2015. GI Journal No. 75 4 November 26, 2015 NEW G.I APPLICATION DETAILS App.No. Geographical Indications Class Goods 530 Tulaipanji Rice 31 Agricultural 531 Gobindobhog Rice 31 Agricultural 532 Mysore Silk 24, 25 and 26 Handicraft 533 Banglar Rasogolla 30 Food Stuffs 534 Lamphun Brocade Thai Silk 24 Textiles GI Journal No. -

The Sari Ebook

THE SARI PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mukulika Banerjee | 288 pages | 16 Sep 2008 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781847883148 | English | London, United Kingdom The Sari PDF Book Anushka Sharma. So shop for yourself or gift a sari to someone, we have something for everyone. The wavy bun completed her look. Face Deal. Long-time weaving families have found themselves out of work , their looms worthless. Sari , also spelled saree , principal outer garment of women of the Indian subcontinent, consisting of a piece of often brightly coloured, frequently embroidered, silk , cotton , or, in recent years, synthetic cloth five to seven yards long. But for some in Asian American communities, the prospect of the nation's first Black and South Asian Vice President wearing a traditional sari at any of the inauguration events -- even if the celebrations are largely virtual -- has offered a glimmer of positivity amid the tumult. Zari Work. As a politician, Dimple Kapadia's sarees were definitely in tune with the sensibilities but she made a point of draping elegant and minimal saree. Batik Sarees. Party Wear. Pandadi Saree. While she draped handloom sarees in the series, she redefined a politician's look with meticulous fashion sensibility. Test your visual vocabulary with our question challenge! Vintage Sarees. Hence there are the tie-dye Bandhani sarees, Chanderi cotton sarees and the numerous silk saree varieties including the Kanchipuram, Banarasi and Mysore sarees. You can even apply the filter as per the need and choose whatever fulfil your requirements in the best way. Yes No. Valam Prints. Green woven cotton silk saree. Though it's just speculation at this stage, and it's uncertain whether the traditional ball will even go ahead, Harris has already demonstrated a willingness to use her platform to make sartorial statements. -

Pahari Miniature Schools

The Art Of Eurasia Искусство Евразии No. 1 (1) ● 2015 № 1 (1) ● 2015 eISSN 2518-7767 DOI 10.25712/ASTU.2518-7767.2015.01.002 PAHARI MINIATURE SCHOOLS Om Chand Handa Doctor of history and literature, Director of Infinity Foundation, Honorary Member of Kalp Foundation. India, Shimla. [email protected] Scientific translation: I.V. Fotieva. Abstract The article is devoted to the study of miniature painting in the Himalayas – the Pahari Miniature Painting school. The author focuses on the formation and development of this artistic tradition in the art of India, as well as the features of technics, stylistic and thematic varieties of miniatures on paper and embroidery painting. Keywords: fine-arts of India, genesis, Pahari Miniature Painting, Basohali style, Mughal era, paper miniature, embroidery painting. Bibliographic description for citation: Handa O.C. Pahari miniature schools. Iskusstvo Evrazii – The Art of Eurasia, 2015, No. 1 (1), pp. 25-48. DOI: 10.25712/ASTU.2518-7767.2015.01.002. Available at: https://readymag.com/622940/8/ (In Russian & English). Before we start discussion on the miniature painting in the Himalayan region, known popularly the world over as the Pahari Painting or the Pahari Miniature Painting, it may be necessary to trace the genesis of this fine art tradition in the native roots and the associated alien factors that encouraged its effloresces in various stylistic and thematic varieties. In fact, painting has since ages past remained an art of the common people that the people have been executing on various festive occasions. However, the folk arts tend to become refined and complex in the hands of the few gifted ones among the common folks. -

Khabbar Vol. XXXIX No. 3 (July, August, September

Khabbar North American Konkani Newsletter Volume XXXIX No. 3 July, August, September - 2016 From: The Honorary Editor, "Khabbar" P. O. Box 222 Lake Jackson, TX77566 - 0222 XXXIX-3 ADDRESS SERVICE REQUESTED FIRST CLASS TO: Khabbar XXXIX No. 3 Page: 1 Khabbar Follies In this section, Khabbar looks into the Konkani community and anything and everything that is Konkani from a Konkani point of view. The names will never be published but geographic location will be identified in general terms. There is no doubt in my mind that Khabbar is a part & parcel of life of Konkanis in North America. In fact, Khabbar has developed a special relation with most of the Konkani families and here are some examples of those close encounters of a different kind….…… The Konkani Sammelan 2016 in Atlanta was a fabulous event. everybody’s relief, at the end of the sammelan, there was a Kudos to the Team KAOG who did an outstanding job for a surplus! successful sammelan. But, the financial situation was bleak! Before the sammelan started, there was a forecast of heavy Thanks to everyone who came to the rescue to make KS-2016 deficit!! For various reasons, the anticipated fund raising did a complete success. not materialize. Team NAKA and Team KAOG did an extreme fund raising and the Konkani community at large Editor’s Reply: opened their heart and the wallet. All said and done, to Now, that is what I say is the Konkani spirit. ***** SUBSCRIPTION FORM: Dear Konkani family, It is time to renew your subscription for 2016.The numbers on the mailing label clearly indicate the year/s the dues for Khabbar has been received since 2014. -

Contemporay Trends in Chikankari

© 2020 IJRAR February 2020, Volume 7, Issue 1 www.ijrar.org (E-ISSN 2348-1269, P- ISSN 2349-5138) CONTEMPORAY TRENDS IN CHIKANKARI 1Reena S. Pandey , 2 Dr. Subhash Pawar 1Research Scholar , 2Adjunct Professor 1Faculty of Art & Design, 1Vishwakarma University , Pune, India Abstract : “Chikankari – Beauty on White “ as its main centre of focus, where its existence over the time is being studied with the different evolution it has shown in its products. Chikankari is a distinctive integral part of Lucknow culture. In India it is believed that Chikan embroidery may have existed from times immemorial. It is said that Noor Jahan brought this craft to India and later it was whole- heartedly adopted by the Nawabs of Lucknow. Thus it became a part of the culture of Lucknow. The embroidery work on clothes was a common feature. In ancient and medieval periods embroidery may have been more popular among the elites but in the present age it is common even among the masses. Because of which nowadays the market is flooded with coarsely executed work and thoughtless design diversifications which has eroded the sensibility of the craft. IndexTerms - Elegant, fine, extravagant, global presence, coarsely designs, elite class. I. INTRODUCTION “Fashion is architecture. It is a matter of proportions”, said Coco Chanel, (Sieve Wright, 2007) Chikankari is a traditional embroidery style from Lucknow, India. It’s an art, which results in the transformation of the plainest cotton and organdie into flowing yards of magic. Chikankari is subtle embroidery, white on white, in which minute and delicate stitches stand out as textural contrasts, shadows and traceries. -

Chamba Rumal, Geographical Indication (GI)” Funded By: MSME

Proceedings of Half Day Workshop on “Chamba Rumal, Geographical Indication (GI)” Funded by: MSME. Govt. of India Venue: Bachat Bhawan , Chamba Date: 19.4.2017 Organized by State Council for Science, Technology & Environment, H.P The State Council for Science, Technology & Environment(SCSTE), Shimla organized a One Day Awareness Workshop on “Chamba Rumal: Geographical Indication” for Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) for the Chamba Rumal artisans at Bachat Bhawan, Chamba on 19th March,2017.Additional District Magistrate, Distt. Chamba, Sh.Shubh Karan Singh was the Chief Guest on the occasion while Padamshree Vijay Sharma, Chamba Rumal expert was the guest of honour. Other dignitaries present on the occasion included Sh. Kunal Satyarthi, IFS, Joint Member Secretary, SCSTE, Sh. Omkar Singh , Manager, District Industries Centre and National Awardees- Kamla Nayeer, Lalita Vakil. On behalf of host organization Dr. Aparna Sharma, Senior Scientific Officer, Sh. Shashi Dhar Sharma, SSA, Ms. Ritika Kanwar, Scientist B and Mr. Ankush Prakash Sharma, Project Scientist were present during the workshop. Inaugural Session: Dr.Aparna Sharma, Senior Scientific Officer, SCSTE Shimla welcomed all the dignitaries, resource persons, Chamba Rumal artisans and the print and electronic media at the workshop on behalf of the State Council for Science, Technology & Environment, H.P. She elaborated on the GIs registered by the Council. Kullu shawl was the first GI to be registered in 2004, Kangra Tea (2005), Chamba Rumal (2007), Kinnauri Shawl (2008) and Kangra Paintings (2012) are other GIs Welcome address by Dr. Aparrna Sharma, Senior Scientific Officer State Council for registered by HPPIC. The applications for Chulli Oil and Science, Technology & Environment Kala Zeera are in the final stages of processing with the GI Registry Office. -

Chikan – a Way of Life by Ruth Chakravarty

N° de projet :ALA/95/23 - 2003/77077 Chikan – A Way of Life By Ruth Chakravarty Chikankari is an ancient form of white floral embroidery, intricately worked with needle and raw thread. Its delicacy is mesmeric. For centuries, this fine white tracery on transparent white fabric has delighted the heart of king and commoner alike. It is centered mainly in the northern heartland of India, namely Lucknow, the capital of a large state, called Uttar Pradesh. It is a complex and elegant craft that has come down to us, evolving, over the years into an aesthetic form of great beauty. That it has survived the loss of royal patronage, suffered deeply at the hands of commercialization, lost its way sometimes in mediocrity and yet stayed alive, is a tribute to the skill and will of the craftspersons who have handed down this technique from one generation to another. There exist several kinds of white embroidery in Europe and across the world, each unique and distinct. Students of this craft like to believe that all forms of embroidery, in some way influence, imitate or complement each other. That may be true to some extent, but right at the onset, let me say that Chikankari is a genre quite unique from other embroideries. Chikankari is at once, simple and elegant, subtle and ornate. This heavy embroidery intricately worked on fine white muslin created a magical effect uniquely its own. The light embroidered fabric was most appropriate for the heat and dust of the North Indian summers. From the time of its inception, Chikan garments spelt class and craft.