Camping Anthropomorphism in Roar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The People of Leonardo's Basement

The people of 26. Ant, or Anthony Davis 58. Fred Rogers Leonardo’s Basement 27. Slug, or Sean Daley 59. Steve Jevning The people - in popular culture, 28. Tony Sanneh 60. Tracy Nielsen business, politics, engineering, art, and technology - chosen for the 29. Lin-Manuel Miranda 61. Albert Einstein album cover redux have provided 30. Joan (of Art) Mondale 62. Maria Montessori inspiration to Leonardo’s Basement for 20 years. Many have a connection 31. Herbert Sellner 63. Nikola Tesla to Minnesota! 32. H.G. Wells 64. Leonardo da Vinci 1. Richard Dean Anderson, or 33. Rose Totino 65. Neal deGrasse Tyson MacGyver 34. Heidemarie Stefanyshyn- 66. John Dewey 2. Kofi Annan Piper 67. Frances McDormand or 3. Dave Arneson 35. Louie Anderson Marge Gunderson 4. Earl Bakken 36. Jeannette Piccard 68. Rocket girl 5. Ann Bancroft 37. Barry Kudrowitz 69. Ada Lovelace 6. Clyde Bellecourt 38. Jane Russell 70. Mary Tyler Moore or Mary Richards 7. Leeann Chin 39. Winona Ryder 71. Newton’s Apple 8. Judy Garland 40. June Marlowe 72. Wendell Anderson 9. Terry Lewis 41. Gordon Parks 73. Ralph Samuelson 10. Jimmy Jam 42. August Wilson 74. Jessica Lange 11. Kate DiCamillo 43. Rebecca Schatz 75. Trojan Horse 12. Dessa, or Margret Wander 44. Fred Rose 76. TARDIS 13. Walter Deubner 45. Cheryl Moeller 77. Cardboard castle 14. Reyn Guyer 46. Paul Bunyan 78. Millennium Falcon 15. Bob Dylan (Another Side of) 47. Mona Lisa 79. Chicken 16. Louise Erdich 48. Rocket J. "Rocky" Squirrel 80. Drum head, inspired by 17. Peter Docter 49. Bullwinkle J. -

Hitchcock's Appetites

McKittrick, Casey. "Epilogue." Hitchcock’s Appetites: The corpulent plots of desire and dread. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 159–163. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 28 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501311642.0011>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 28 September 2021, 08:18 UTC. Copyright © Casey McKittrick 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. Epilogue itchcock and his works continue to experience life among generation Y Hand beyond, though it is admittedly disconcerting to walk into an undergraduate lecture hall and see few, if any, lights go on at the mention of his name. Disconcerting as it may be, all ill feelings are forgotten when I watch an auditorium of eighteen- to twenty-one-year-olds transported by the emotions, the humor, and the compulsions of his cinema. But certainly the college classroom is not the only guardian of Hitchcock ’ s fl ame. His fi lms still play at retrospectives, in fi lm festivals, in the rising number of fi lm studies classes in high schools, on Turner Classic Movies, and other networks devoted to the “ oldies. ” The wonderful Bates Motel has emerged as a TV serial prequel to Psycho , illustrating the formative years of Norman Bates; it will see a second season in the coming months. Alfred Hitchcock Presents and The Alfred Hitchcock Hour are still in strong syndication. Both his fi lms and television shows do very well in collections and singly on Amazon and other e-commerce sites. -

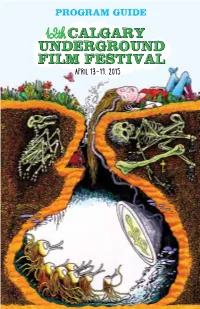

Program Guide

PROGRAM GUIDE SATURDAY. APRIL 18 | 7:00PM SWIM LITTLE FISH SWIM TICKET & VENUE INFORMATION VENUE Globe Cinema - 617 8 Ave. SW SINGLE TICKETS Opening Night Film Screening & Party $12 Saturday Morning Cartoon Party $12 Kids 6 & under $6 Regular Admission $10 ON CUFF Members, Students & Seniors $8.25 PUNCH PASS rmati O F N 5 Film Punch Pass $40 I E Excludes Saturday Morning Cartoon Party/Opening Night Film). U Punch pass can be shared, used for more than one ticket per screening, and for year-round programming. & VEN FESTIVAL PASSES T KE IC Early Bird Pass $99 Regular Festival Pass $120 | T AL Tickets for pass holders are available at all screenings. We V recommend arriving 30-45 min prior to start time to ensure entry. STI E F LICENSED 18+ All screenings after 3PM are licensed (18+), which means you can FILM drink beer during the film (!) but NO MINORS. Early matinees are D N all ages. U O FESTIVAL BOX OFFICE R G R 1. Online at www.calgaryundergroundfilm.com E D 2. Globe Cinema Box Office (during festival hours only) N U MEMBERSHIPS ary G Purchase a lifetime membership for $10 AL from the festival merchandise table, or at C H www.calgaryundergroundfilm.com. Add your T membership tag to your keychain, and get 12 discounts at all CUFF screenings, the festival bar, and special offers throughout the year. 12 PARTIES SPONSORS MondaY, APRIL 13 FUNDING Partners 9 PM OPENING NIGHT AFTERPARTY! Sole Korea Restaurant 628 8 Ave SW $12 (includes screening and afterparty). Come join us for a party following Ex Machina (p. -

It Must Be Karma: the Story of Vicki Joy and Johnnymoon

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-14-2010 It Must be Karma: The Story of Vicki Joy and Johnnymoon Richard Bolner University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Bolner, Richard, "It Must be Karma: The Story of Vicki Joy and Johnnymoon" (2010). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1121. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1121 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. It Must be Karma: The Story of Vicki Joy and Johnnymoon A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Fine Arts in Film, Theatre and Communication Arts Creative Writing by Rick Bolner B.S. University of New Orleans, 1982 May, 2010 Table of Contents Prologue ...............................................................................................................................1 -

OVERVIEW of Who Is Big Cat Rescue?

Big Cat Rescue in Tampa Florida Who Is Big Cat Rescue 1 Table Of Contents Chapter 2 - Who Is Big Cat Rescue Chapter 3 - Non-Profit Ratings Chapter 4 - Award Winning Sanctuary Chapter 5 - Cable Television Segments Chapter 6 - Celebrity Supporters Chapter 7 - Area Business Affiliations Chapter 8 - How Big Cat Rescue Started Chapter 9 - The History & Evolution of Big Cat Rescue Chapter 10 - Cat Links 1 2 Who Is Big Cat Rescue OVERVIEW of Who is Big Cat Rescue? Big Cat Rescue is the largest accredited sanctu- ary in the world dedicated entirely to abused and abandoned big cats. We are home to over 100 lions, tigers, bobcats, cougars and other species most of whom have been abandoned, abused, orphaned, saved from being turned into fur coats, or retired from performing acts. Our dual mission is to provide the best home we can for the cats in our care and educate the pub- lic about the plight of these majestic animals, both in captivity and in the wild, to end abuse and avoid extinction. The sanctuary began in 1992 when the Founder, Carole Baskin, and her then husband Don, mistakenly believing that bobcats made good pets, went looking to buy some kit- tens. They inadvertently ended up at a “fur farm” and bought all 56 kittens to keep them from being turned into fur coats. See How We Started. In the early years, influenced by breeders and pet owners, they believed that the cats made suitable pets and that breeding and placing the cats in homes was a way to “pre- serve the species.” Gradually they saw increasing evidence that not only was this not the case, but that it was leading to a consistent pattern of suffering and abuse. -

North Coaster

North Coaster Writing — Photography — Marin and Sonoma Coast Travel Directory North Coaster A journal for travelers along the Marin and Sonoma coasts The Greater Horror by Thomas Broderick Page 3 Bird identification made easy by Samantha KimmeyPage 5 Beach day by Jordan Bowen Page 7 Tule elk lament by Jim Pelligrin Page 7 The word by Samantha Kimmey Page 8 Ain’t misbehavin’ by Scott McMorrow Page 9 The new you by Samantha Kimmey Page 10 Travel directory Page 19 Print by Miguel Kuntz Page 21 Photographs by David Briggs Edited by Tess Elliott Published by the Point Reyes Light, LLC Box 210, Point Reyes Station, CA 94956 (415) 669.1200 ptreyeslight.com The greater horror By Thomas Broderick Last year, I had the pleasure of spotting Tippi Hedren, star of Alfred Hitchcock’s 1963 film “The Birds,” signing autographs at The Tides restaurant in Bodega Bay. She was my second celebrity encounter since moving back to Northern California last year, the first being a certain celebrity chef cutting me off on Highway 12. I later learned that Ms. Hedren’s appearance is an annual tradition, and that some of the money she makes from it goes to support her extensive charity work. Though I’ve never seen the film in its entirety, I learned the story through multiple trips to the restaurant and the Saint Teresa of Avila Church in Bodega. Even I, who spent the majority of my life in Middle Tennessee, feel local pride knowing these beautiful places are immortalized in such a loved and influential film. -

The Guardian, November 14, 1989

Wright State University CORE Scholar The Guardian Student Newspaper Student Activities 11-14-1989 The Guardian, November 14, 1989 Wright State University Student Body Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/guardian Part of the Mass Communication Commons Repository Citation Wright State University Student Body (1989). The Guardian, November 14, 1989. : Wright State University. This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Activities at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Guardian Student Newspaper by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Title Won! Zany Events Paul McCartney etters capture Wright State tournament title Find out what's happening at other campuses Read about the Beatle's Showtirne special Page 3 Page4 Page 5 ....""rhorst resigns as General anager of WWSU a k d for a po ition de cription to be po ted by student employment .. we became aware that agreeing on a new po ition description Craig Barhorst re igned as general man would be more difficult than we previously of the WSU tudent-operated radio sta thought." WWSU,as of ovember 9. Jay Rainaldi Karyn S. Campbell, Student Media Coor ducting general manager of the talion. dinator and al o a member of the media 'traig left for per onal rea on ," committee, said, "The old po ition descrip di said in an interview. "He ju t felt tion was vague, and the people at the radio was more important and that he station that I have talked to agree it's vague." 't do everything at once. -

Throughout the Centuries, Muses Defined Those

hroughout the centuries, muses defined those people Twho have fueled the creative imaginations of the great minds of their day: artists, filmmakers, poets, fashion designers, musicians and writers. Many years ago, there existed a woman by the name of Jacqueline LaBelle. Born into a family of successful French immigrants, she rose to fame at seventeen as the youngest heiress in Philadelphia society. LaBelle was a jet-set member of the international beau mode, and a style icon to fashion designers and artists the world over. She was known for her signature kohl-lined eyes, imperial guard-inspired fur lined jackets and magnificent collection of sapphire jewelry. She was elegant, venerated and very much the muse. For her extravagant parties at her mansion in Rittenhouse Square, she spared no expense importing the best French cuisine and libations. Her servants were directed to “continually toss handfuls of copper filings onto the flames, transforming them into blazes of vivid blue” to add a dramatic atmosphere. The parties were a fabulous collision of social, art, fashion, Hollywood, political and literary stars. It was THE place to see and be seen and the place where inspired ideas were born. Jacqueline LaBelle was daring, adventurous, intangible and always at the center of it all. Le RAW BAR {Je l’aime raw} Oysters on the Half Shell * Half Dozen 16 / Baker’s Dozen 32 Mignonette Granita / Horseradish Cocktail Sauce Jumbo Shrimp Cocktail 17 Horseradish Cocktail Sauce Chesapeake Bay Jumbo Lump Blue Crab Meat 19 Mustard Sauce Chilled Shellfish Tower * Serves Two 36 / Serves Four 70 Shrimp / Oysters / Seasonal Stone Crab Claws / Chesapeake Bay Jumbo Blue Lump Crab Meat / Mustard Sauce / Mignonette Granita / Horseradish Cocktail Sauce TARTES FLAMBÉES {Alsace Pizza} Classic 13 Fromage Blanc / Caramelized Onions / Lardon Margherita 14 Tomato / Bufala Mozzarella / Fresh Basil Goat Cheese 15 Pistachios / Red Onion / Truffle Honey Smoke + Veil, Paris 1957 (Vogue) © William Klein. -

Sunday Morning, Oct. 28

SUNDAY MORNING, OCT. 28 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM Good Morning America (N) (cc) KATU News This Morning - Sun (N) (cc) Your Voice, Your Paid This Week With George Stepha- Paid Paid 2/KATU 2 2 Vote nopoulos (N) (cc) (TVG) Paid Paid CBS News Sunday Morning (N) (cc) Face the Nation The NFL Today (N) (Live) (cc) NFL Football Indianapolis Colts at Tennessee Titans. (N) (Live) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (N) (cc) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise (N) (cc) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 7:00 AM (N) (cc) Meet the Press (N) (cc) (TVG) Paid Paid Figure Skating ISU Grand Prix of 8/KGW 8 8 Figure Skating: Skate Canada. (N) Betsy’s Kinder- Angelina Balle- Mister Rogers’ Daniel Tiger’s Thomas & Friends Bob the Builder Rick Steves’ Travels to the Nature Snowy owls on the North NOVA A 5,000-year-old mummi- 10/KOPB 10 10 garten rina: Next Neighborhood Neighborhood (TVY) (TVY) Europe (TVG) Edge Slope of Alaska. (TVPG) fied corpse. (cc) (TVPG) FOX News Sunday With Chris Wallace Good Day Oregon Sunday (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) (Live) (cc) NFL Football Seattle Seahawks at Detroit Lions. (N) (Live) (cc) 12/KPTV 12 12 (cc) (TVPG) (TVPG) Paid Paid Turning Point: Day of Discovery In Touch With Dr. Charles Stanley Life Change Paid Paid Paid Inspiration Today Camp Meeting 22/KPXG 5 5 David Jeremiah (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) Kingdom Con- Turning Point (cc) Praise W/Kenneth Winning Walk (cc) A Miracle For You Redemption (cc) Love Worth Find- In Touch (cc) PowerPoint With It Is Written (cc) Answers With From His Heart 24/KNMT 20 20 nection (TVPG) Hagin (TVG) (cc) ing (TVG) (TVPG) Jack Graham. -

676 Grads Get Jobs Through Placement Center

676 grads get jobs through placement center By Katie McClare acquire positions by using the ters, said Doherty, placement do. We provide information declined by 4 per cent. About About half of all students personal skills obtained through personnel arrange interviews, about what the employment 89 per cent of all offers are com graduating from UNH who re the use of the office. This, he identify employers, formulate m arket is like, so th ey ’ll know ing from the engineering and spond to Career Planning and said, is the main function of the letters of application and in what’s out there.” business fields. Placement before and after service. quiry, and prepare personal Quoting figures issued by the While job offers from federal graduation obtain their desired “Students think of this office resumes, among other things. He College Placement Service, and state employers and school positions, according to Career as a ‘thing’ on campus to get you said that 802 seniors have regis Doherty said that although the systems went down this year, Planning and Placement Director a job. It is actually more of an tered. outlook for the job m arket is those in business, industry, and Edward Doherty. informational service which The placem ent service is open not good, it is slowly improving. non-profit organizations in Approximately 50 per cent of helps you acquire the skills to to all students, not just seniors. He said that positions in the creased, Doherty continued. UNH students use the placement place yourself in a job. What we “We are here to serve everyone, humanities and social science Doherty said that a lot of the service located in Huddleston try to do is give the student an from the first year,” said disciplines are experiencing a 26 jobs being offered do not direct Hall, said Doherty. -

Ebook Download Roar Ebook, Epub

ROAR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Stacy Sims,Selene Yeager | 304 pages | 18 Jul 2016 | Rodale Press Inc. | 9781623366865 | English | Emmaus, United States Roar PDF Book The Best Horror Movies on Netflix. Marshall and Hedren began keeping young lions that they had acquired from zoos and circuses in their house in Sherman Oaks. The film was fully completed after 11 years in production. The Awl. John Jerry Marshall Mativo Frank Tom Official Sites. Crazy Credits. The Guardian. Take the quiz Forms of Government Quiz Name that government! External Sites. Save Word. Edit Did You Know? Now I'm floating like a butterfly Stinging like a bee I earned my stripes I went from zero, to my own hero. Archived from the original on August 1, Trivia In , a flood from a dam break killed many lions in the film, washed away the set and destroyed nearly all of the movie, including ranch property, personal possessions, film sets, editing equipment, completed film footage and three key lions including Robbie, the movie's lion king. Error: please try again. Archived from the original on September 23, Archived from the original on March 25, Director: Noel Marshall. Box Office Mojo. They decided to make a film centered around that theme, bringing rescued big cats into their homes in California and living with them. Panama City News Herald. Edit Details Official Sites: Official site. Retrieved June 16, Send us feedback. Nominated for 1 Primetime Emmy. Redirected from Roar film. Choose an adventure below and discover your next favorite movie or TV show. Keep track of everything you watch; tell your friends. -

Tippi Hedren Receives the Press Club’S Visionary Award for Public Service

2017 VISIONARY AWARD A Momentous Life, From ‘The Birds’ to BIG CATS Movie Star, Model and Activist Tippi Hedren Receives the Press Club’s Visionary Award for Public Service BY CHRISTOPHER PALMERI IPPI HEDREN won international acclaim for her Hedren lives at Shambala Preserve, portrayal of a young socialite attacked by seagulls located in the high desert outside of in the Alfred Hitchcock thriller The Birds. Tonight, Los Angeles. she is being honored by the Los Angeles Press Club Far left, Hitchcock and actor Sean Tfor her fve-decade commitment to protecting big cats. Connery during the flming of Marnie. Since 1983, Hedren, the movie star, model, activist and Left, Hedren with Buddy, an acquaintance from The Birds. mother, has been operating the Shambala Preserve, an 80- acre sanctuary near Palmdale, California, where she has helped rescue more than 235 lions, tigers, cougars and other exotic felines. The cats have come to her from sources such as the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Humane Society. At Shambala, in the Mojave Desert, they fnd a permanent, loving home. The size difference between an adult male lion like Leo and Hedren makes the point why big cats do not make appropriate pets. “Our only purpose is to allow these magnifcent animals to live out their lives with care, understanding and dignity,” Hedren explains in the Shambala mission statement. seeing her on TV in a diet drink commercial. After a series can Film Institute. It set the bar for other intelligent thrillers In a series of books by author Donald Spoto, Hedren For that commitment, and all her groundbreaking work, of screen tests and acting lesson from the British director, from Jaws to the current hit It.