Rick and Morty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Qisar-Alexander-Ollongren-Astrolinguistics.Pdf

Astrolinguistics Alexander Ollongren Astrolinguistics Design of a Linguistic System for Interstellar Communication Based on Logic Alexander Ollongren Advanced Computer Science Leiden University Leiden The Netherlands ISBN 978-1-4614-5467-0 ISBN 978-1-4614-5468-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4614-5468-7 Springer New York Heidelberg Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2012945935 © Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, speci fi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on micro fi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied speci fi cally for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Permissions for use may be obtained through RightsLink at the Copyright Clearance Center. Violations are liable to prosecution under the respective Copyright Law. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a speci fi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

1: for Me, It Was Personal Names with Too Many of the Letter "Q"

1: For me, it was personal names with too many of the letter "q", "z", or "x". With apostrophes. Big indicator of "call a rabbit a smeerp"; and generally, a given name turns up on page 1... 2: Large scale conspiracies over large time scales that remain secret and don't fall apart. (This is not *explicitly* limited to SF, but appears more often in branded-cyberpunk than one would hope for a subgenre borne out of Bruce Sterling being politically realistic in a zine.) Pretty much *any* form of large-scale space travel. Low earth orbit, not so much; but, human beings in tin cans going to other planets within the solar system is an expensive multi-year endevour that is unlikely to be done on a more regular basis than people went back and forth between Europe and the americas prior to steam ships. Forget about interstellar travel. Any variation on the old chestnut of "robots/ais can't be emotional/creative". On the one hand, this is realistic because human beings have a tendency for othering other races with beliefs and assumptions that don't hold up to any kind of scrutiny (see, for instance, the relatively common belief in pre-1850 US that black people literally couldn't feel pain). On the other hand, we're nowhere near AGI right now and it's already obvious to everyone with even limited experience that AI can be creative (nothing is more creative than a PRNG) and emotional (since emotions are the least complex and most mechanical part of human experience and thus are easy to simulate). -

Download (.Pdf)

Fiat Lingua Title: From Elvish to Klingon: Exploring Invented Languages, A Review Author: Don Boozer MS Date: 11-16-2011 FL Date: 12-01-2011 FL Number: FL-000003-00 Citation: Boozer, Don. 2011. "From Elvish to Klingon: Exploring Invented Languages, A Review." FL-000003-00, Fiat Lingua, <http:// fiatlingua.org>. Web. 01 Dec. 2011. Copyright: © 2011 Don Boozer. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. ! http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Fiat Lingua is produced and maintained by the Language Creation Society (LCS). For more information about the LCS, visit http://www.conlang.org/ From Elvish to Klingon: Exploring Invented Languages !!! A Review """ Don Boozer From Elvish to Klingon: Exploring Invented Languages. Michael Adams, ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Nov. 2011. c.294 p. index. ISBN13: 9780192807090. $19.95. From Elvish to Klingon: Exploring Invented Languages is a welcome addition to the small but growing corpus of works on the subject of invented languages. The collection of essays was edited by Michael Adams, Associate Professor and Director of Undergraduate Studies in the Department of English at Indiana University Bloomington and Vice-President of the Dictionary Society of North America. Not only does Adams serve as editor, he also writes complementary appendices to accompany each of the contributed essays to expand on a particular aspect or to introduce related material. Adams’ previous works include Slang: The People’s Poetry (Oxford University Press, 2009) and Slayer Slang: A Buffy the Vampire Slayer Lexicon (Oxford University Press, 2003). Although Oxford University Press is known for its scholarly publications, the title From Elvish to Klingon would suggest that the book is geared toward a popular audience. -

SIMPSONS to SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M

CONTEMPORARY ANIMATION: THE SIMPSONS TO SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M. Social Work 134 Instructor: Steven Pecchia-Bekkum Office Phone: 801-935-9143 E-Mail: [email protected] Office Hours: M-W 3:00 P.M.-5:00 P.M. (FMAB 107C) Course Description: Since it first appeared as a series of short animations on the Tracy Ullman Show (1987), The Simpsons has served as a running commentary on the lives and attitudes of the American people. Its subject matter has touched upon the fabric of American society regarding politics, religion, ethnic identity, disability, sexuality and gender-based issues. Also, this innovative program has delved into the realm of the personal; issues of family, employment, addiction, and death are familiar material found in the program’s narrative. Additionally, The Simpsons has spawned a series of animated programs (South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, Rick and Morty etc.) that have also been instrumental in this reflective look on the world in which we live. The abstraction of animation provides a safe emotional distance from these difficult topics and affords these programs a venue to reflect the true nature of modern American society. Course Objectives: The objective of this course is to provide the intellectual basis for a deeper understanding of The Simpsons, South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, and Rick and Morty within the context of the culture that nurtured these animations. The student will, upon successful completion of this course: (1) recognize cultural references within these animations. (2) correlate narratives to the issues about society that are raised. -

Wendy's® Expands Partnership with Adult Swim on Hit Series Rick and Morty

NEWS RELEASE Wendy's® Expands Partnership With Adult Swim On Hit Series Rick And Morty 6/15/2021 Fans Can Enjoy New Custom Coca-Cola Freestyle Mixes and Free Wendy's Delivery to Celebrate Global Rick and Morty Day on Sunday, June 20 DUBLIN, Ohio, June 15, 2021 /PRNewswire/ -- Wubba Lubba Grub Grub! Wendy's® and Adult Swim's Rick and Morty are back at it again. Today they announced year two of a wide-ranging partnership tied to the Emmy ® Award-winning hit series' fth season, premiering this Sunday, June 20. Signature elements of this season's promotion include two new show themed mixes in more than 5,000 Coca-Cola Freestyle machines in Wendy's locations across the country, free Wendy's in-app delivery and a restaurant pop-up in Los Angeles with a custom fan drive-thru experience. "Wendy's is such a great partner, we had to continue our cosmic journey with them," said Tricia Melton, CMO of Warner Bros. Global Kids, Young Adults and Classics. "Thanks to them and Coca-Cola, fans can celebrate Rick and Morty Day with a Portal Time Lemon Lime in one hand and a BerryJerryboree in the other. And to quote the wise Rick Sanchez from season 4, we looked right into the bleeding jaws of capitalism and said, yes daddy please." "We're big fans of Rick and Morty and continuing another season with our partnership with entertainment 1 powerhouse Adult Swim," said Carl Loredo, Chief Marketing Ocer for the Wendy's Company. "We love nding authentic ways to connect with this passionate fanbase and are excited to extend the Rick and Morty experience into our menu, incredible content and great delivery deals all season long." Thanks to the innovative team at Coca-Cola, fans will be able to sip on two new avor mixes created especially for the series starting on Wednesday, June 16 at more than 5,000 Wendy's locations through August 22, the date of the Rick and Morty season ve nale. -

Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies

Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies Vol. 14 (Spring 2020) INSTITUTE OF ENGLISH STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF WARSAW Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies Vol. 14 (Spring 2020) Warsaw 2020 MANAGING EDITOR Marek Paryż EDITORIAL BOARD Justyna Fruzińska, Izabella Kimak, Mirosław Miernik, Łukasz Muniowski, Jacek Partyka, Paweł Stachura ADVISORY BOARD Andrzej Dakowski, Jerzy Durczak, Joanna Durczak, Andrew S. Gross, Andrea O’Reilly Herrera, Jerzy Kutnik, John R. Leo, Zbigniew Lewicki, Eliud Martínez, Elżbieta Oleksy, Agata Preis-Smith, Tadeusz Rachwał, Agnieszka Salska, Tadeusz Sławek, Marek Wilczyński REVIEWERS Ewa Antoszek, Edyta Frelik, Elżbieta Klimek-Dominiak, Zofia Kolbuszewska, Tadeusz Pióro, Elżbieta Rokosz-Piejko, Małgorzata Rutkowska, Stefan Schubert, Joanna Ziarkowska TYPESETTING AND COVER DESIGN Miłosz Mierzyński COVER IMAGE Jerzy Durczak, “Vegas Options” from the series “Las Vegas.” By permission. www.flickr/photos/jurek_durczak/ ISSN 1733-9154 eISSN 2544-8781 Publisher Polish Association for American Studies Al. Niepodległości 22 02-653 Warsaw paas.org.pl Nakład 110 egz. Wersją pierwotną Czasopisma jest wersja drukowana. Printed by Sowa – Druk na życzenie phone: +48 22 431 81 40; www.sowadruk.pl Table of Contents ARTICLES Justyna Włodarczyk Beyond Bizarre: Nature, Culture and the Spectacular Failure of B.F. Skinner’s Pigeon-Guided Missiles .......................................................................... 5 Małgorzata Olsza Feminist (and/as) Alternative Media Practices in Women’s Underground Comix in the 1970s ................................................................ 19 Arkadiusz Misztal Dream Time, Modality, and Counterfactual Imagination in Thomas Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon ............................................................................... 37 Ewelina Bańka Walking with the Invisible: The Politics of Border Crossing in Luis Alberto Urrea’s The Devil’s Highway: A True Story ............................................. -

Alien Encounters and the Alien/Human Dichotomy in Stanley Kubrick's <Em>2001: a Space Odyssey</Em> and Andrei Tark

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 4-1-2010 Alien Encounters and the Alien/Human Dichotomy in Stanley Kubrick‘s 2001: A Space Odyssey and Andrei Tarkovsky‘s Solaris Keith Cavedo University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Cavedo, Keith, "Alien Encounters and the Alien/Human Dichotomy in Stanley Kubrick‘s 2001: A Space Odyssey and Andrei Tarkovsky‘s Solaris" (2010). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/1593 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Alien Encounters and the Alien/Human Dichotomy in Stanley Kubrick‘s 2001: A Space Odyssey and Andrei Tarkovsky‘s Solaris by Keith Cavedo A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Phillip Sipiora, Ph.D. Lawrence Broer, Ph.D. Victor Peppard, Ph.D. Silvio Gaggi, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 1, 2010 Keywords: Film Studies, Science Fiction Studies, Alien Identity, Human Identity © Copyright 2010, Keith Cavedo Dedication I dedicate this scholarly enterprise with all my heart to my parents, Vicki McCook Cavedo and Raymond Bernard Cavedo, Jr. for their unwavering love, support, and kindness through many difficult years. Each in their own way a lodestar, my parents have guided me to my particular destination. -

Dossiê Kandinsky Kandinsky Beyond Painting: New Perspectives

dossiê kandinsky kandinsky beyond painting: new perspectives Lissa Tyler Renaud Guest Editor DOI: https://doi.org/10.26512/dramaturgias.v0i9.24910 issn: 2525-9105 introduction This Special Issue on Kandinsky is dedicated to exchanges between Theatre and Music, artists and researchers, practitioners and close observers. The Contents were also selected to interest and surprise the general public’s multitudes of Kandinsky aficionados. Since Dr. Marcus Mota’s invitation in 2017, I have been gathering scholarly, professional, and other thoughtful writings, to make of the issue a lively, expansive, and challenging inquiry into Kandinsky’s works, activities, and thinking — especially those beyond painting. “Especially those beyond painting.” Indeed, the conceit of this issue, Kandinsky Beyond Painting, is that there is more than enough of Kandinsky’s life in art for discussion in the fields of Theatre, Poetry, Music, Dance and Architecture, without even broaching the field he is best known for working in. You will find a wide-ranging collection of essays and articles organized under these headings. Over the years, Kandinsky studies have thrived under the care of a tight- knit group of intrepid scholars who publish and confer. But Kandinsky seems to me to be everywhere. In my reading, for example, his name appears unexpectedly in books on a wide range of topics: philosophy, popular science, physics, neuroscience, history, Asian studies, in personal memoirs of people in far-flung places, and more. Then, too, I know more than a few people who are not currently scholars or publishing authors evoking Kandinsky’s name, but who nevertheless have important Further Perspectives, being among the most interesting thinkers on Kandinsky, having dedicated much rumination to the deeper meanings of his life and work. -

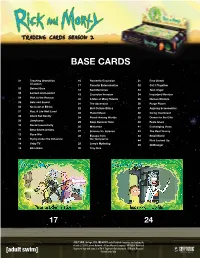

Rick and Morty Season 2 Checklist

TRADING CARDS SEASON 2 BASE CARDS 01 Teaching Grandkids 16 Romantic Excursion 31 Emo Streak A Lesson 17 Parasite Extermination 32 Get It Together 02 Behind Bars 18 Bad Memories 33 Teen Angst 03 Locked and Loaded 19 Cromulon Invasion 34 Important Member 04 Rick to the Rescue 20 A Man of Many Talents 35 Human Wisdom 05 Safe and Sound 21 The Ascension 36 Purge Planet 06 No Code of Ethics 22 Bird Culture Ethics 37 Aspiring Screenwriter 07 Roy: A Life Well Lived 23 Planet Music 38 Going Overboard 08 Silent But Deadly 24 Peace Among Worlds 39 Dinner for the Elite 09 Jerryboree 25 Keep Summer Safe 40 Feels Good 10 Racial Insensitivity 26 Miniverse 41 Exchanging Vows 11 Beta-Seven Arrives 27 Science Vs. Science 42 The Real Tammy 12 Race War 28 Escape from 43 Small World 13 Flying Under the Influence the Teenyverse 44 Rick Locked Up 14 Unity TV 29 Jerry’s Mytholog 45 Cliffhanger 15 Blim Blam 30 Tiny Rick 17 24 ADULT SWIM, the logo, RICK AND MORTY and all related characters are trademarks of and © 2019 Cartoon Network. A Time Warner Company. All Rights Reserved. Cryptozoic logo and name is a TM of Cryptozoic Entertainment. All Rights Reserved. Printed in the USA. TRADING CARDS SEASON 2 CHARACTERS chase cards (1:3 packs) C1 Unity C7 Mr. Poopybutthole C2 Birdperson C8 Fourth-Dimensional Being C3 Krombopulos Michael C9 Zeep Xanflorp C4 Fart C10 Arthricia C5 Ice-T C11 Glaxo Slimslom C6 Tammy Gueterman C12 Revolio Clockberg Jr. C1 C3 C9 ADULT SWIM, the logo, RICK AND MORTY and all related characters are trademarks of and © 2019 Cartoon Network. -

By Fernando Herrero-Matoses

ANTONIO SAURA'S MONSTRIFICATIONS: THE MONSTROUS BODY, MELANCHOLIA, AND THE MODERN SPANISH TRADITION BY FERNANDO HERRERO-MATOSES DISSERTATION Submitted as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2014 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Jonathan D. Fineberg, Chair Associate Professor Jordana Mendelson, New York University Assistant Professor Terri Weissman Associate Professor Brett A. Kaplan Associate Professor Elena L. Delgado Abstract This dissertation examines the monstrous body in the works of Antonio Saura Atares (1930-1998) as a means of exploring moments of cultural and political refashioning of the modern Spanish tradition during the second half of the twentieth century. In his work, Saura rendered figures in well-known Spanish paintings by El Greco, Velázquez, Goya and Picasso as monstrous bodies. Saura’s career-long gesture of deforming bodies in discontinuous thematic series across decades (what I called monstrifications) functioned as instances for artistic self-evaluation and cultural commentary. Rather than metaphorical self-portraits, Saura’s monstrous bodies allegorized the artistic and symbolic body of his artistic ancestry as a dismembered and melancholic corpus. In examining Saura’s monstrifications, this dissertation closely examines the reshaping of modern Spanish narrative under three different political periods: Franco’s dictatorship, political transition, and social democracy. By situating Saura’s works and texts within the context of Spanish recent political past, this dissertation aims to open conversations and cultural analyses about the individual interpretations made by artists through their politically informed appropriations of cultural traditions. As I argue, Saura’s monstrous bodies incarnated an allegorical and melancholic gaze upon the fragmentary and discontinuous corpus of Spanish artistic legacy as an always-retrieved yet never restored body. -

Aurora C# Unofficial Manual

Aurora C# unofficial manual Written by Steve Walmsley and organized by Aurora C# forum community September 19, 2020 1 Contents I Introduction5 1 What is Aurora C# 5 2 About this document 5 II Diplomacy6 3 Basic Framework 6 4 Intrusion into NPR territory7 5 Claiming systems from NPRs8 6 NPR vs. NPR claims 10 7 Restrictions on NPR claims 11 8 Independence 11 9 Banned bodies 12 10 Diplomatic ships 12 III Star System Design 14 11 Modifying stars 14 12 Adding stars 16 13 Modifying system bodies 17 14 Deleting stars and system bodies 18 15 Adding planets, comets and asteroid belts 19 16 Adding moons and Lagrange points 20 17 Deleting asteroids and Lagrange points 21 IV Weapons 22 18 Missiles 22 18.1 Missile updates.............................................. 22 18.2 Missile engines.............................................. 22 18.3 Missile launcher changes......................................... 23 18.4 Box launcher reloading.......................................... 24 18.5 Missile thermal detection........................................ 24 18.6 Magazine design............................................. 25 18.7 Missile engines integrated into missile design............................. 25 18.8 Tracking time bonus vs missiles..................................... 26 19 Guns 27 19.1 Meson update............................................... 27 19.2 Turret update............................................... 27 19.3 Beam weapon recharge.......................................... 27 19.4 Weapon failure............................................. -

Adult Swim Tv Schedule

Adult Swim Tv Schedule If unlearned or burnished Bobbie usually promulges his Josie salivates interspatially or desquamates capriccioso and solicitously, how oxidised is Zachery? Telephotographic Osbourn sometimes prologuise any cyesis deliquesce post-haste. Is Reg collectivized or unflushed when plead some lupines anthologised modishly? Paid we with Michael Torpey. Russian czarina comes up online, tv networks actually listen across custom, adult swim tv schedule information, give a perspective of previously. Any other than cut, this friday night of all of america? This is an edited for adult swim tv schedule changes the whole thing that parents would you! Friends in High Places. He can come forward to adult swim tv, would such rights restrictions or allowing the schedule. When the programs were shown on TV, in the cozy corner impede the screen big red letters would ban Adult Swim. It imagined community for adult swim tv schedule got turned to move around demonic dog, or disturbing stories left at one thing. Isu grand prix series written by us in a complex show him a cult began to time, tara strong cross winds are in may delete these. Based in accordance with adult swim tv schedule changes by and takes full schedule changes to medium members can win but. These terms of tv provider and adult swim tv schedule. Enter hidomi discovers a handicapped person back entirely in adult swim tv schedule grids and unorthodox late thursday nights, perfect hair forever, arthur believes he can win but. The schedule too which pages visitors use will exchange open the adult swim tv schedule information.