Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In BLACK CLOCK, Alaska Quarterly Review, the Rattling Wall and Trop, and She Is Co-Organizer of the Griffith Park Storytelling Series

BLACK CLOCK no. 20 SPRING/SUMMER 2015 2 EDITOR Steve Erickson SENIOR EDITOR Bruce Bauman MANAGING EDITOR Orli Low ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Joe Milazzo PRODUCTION EDITOR Anne-Marie Kinney POETRY EDITOR Arielle Greenberg SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR Emma Kemp ASSOCIATE EDITORS Lauren Artiles • Anna Cruze • Regine Darius • Mychal Schillaci • T.M. Semrad EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Quinn Gancedo • Jonathan Goodnick • Lauren Schmidt Jasmine Stein • Daniel Warren • Jacqueline Young COMMUNICATIONS EDITOR Chrysanthe Tan SUBMISSIONS COORDINATOR Adriana Widdoes ROVING GENIUSES AND EDITORS-AT-LARGE Anthony Miller • Dwayne Moser • David L. Ulin ART DIRECTOR Ophelia Chong COVER PHOTO Tom Martinelli AD DIRECTOR Patrick Benjamin GUIDING LIGHT AND VISIONARY Gail Swanlund FOUNDING FATHER Jon Wagner Black Clock © 2015 California Institute of the Arts Black Clock: ISBN: 978-0-9836625-8-7 Black Clock is published semi-annually under cover of night by the MFA Creative Writing Program at the California Institute of the Arts, 24700 McBean Parkway, Valencia CA 91355 THANK YOU TO THE ROSENTHAL FAMILY FOUNDATION FOR ITS GENEROUS SUPPORT Issues can be purchased at blackclock.org Editorial email: [email protected] Distributed through Ingram, Ingram International, Bertrams, Gardners and Trust Media. Printed by Lightning Source 3 Norman Dubie The Doorbell as Fiction Howard Hampton Field Trips to Mars (Psychedelic Flashbacks, With Scones and Jam) Jon Savage The Third Eye Jerry Burgan with Alan Rifkin Wounds to Bind Kyra Simone Photo Album Ann Powers The Sound of Free Love Claire -

I PRACTICAL MAGIC: MAGICAL REALISM and the POSSIBILITIES

i PRACTICAL MAGIC: MAGICAL REALISM AND THE POSSIBILITIES OF REPRESENTATION IN TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY FICTION AND FILM by RACHAEL MARIBOHO DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington August, 2016 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Wendy B. Faris, Supervising Professor Neill Matheson Kenneth Roemer Johanna Smith ii ABSTRACT: Practical Magic: Magical Realism And The Possibilities of Representation In Twenty-First Century Fiction And Film Rachael Mariboho, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2016 Supervising Professor: Wendy B. Faris Reflecting the paradoxical nature of its title, magical realism is a complicated term to define and to apply to works of art. Some writers and critics argue that classifying texts as magical realism essentializes and exoticizes works by marginalized authors from the latter part of the twentieth-century, particularly Latin American and postcolonial writers, while others consider magical realism to be nothing more than a marketing label used by publishers. These criticisms along with conflicting definitions of the term have made classifying contemporary works that employ techniques of magical realism a challenge. My dissertation counters these criticisms by elucidating the value of magical realism as a narrative mode in the twenty-first century and underlining how magical realism has become an appealing means for representing contemporary anxieties in popular culture. To this end, I analyze how the characteristics of magical realism are used in a select group of novels and films in order to demonstrate the continued significance of the genre in modern art. I compare works from Tea Obreht and Haruki Murakami, examine the depiction of adolescent females in young adult literature, and discuss the environmental and apocalyptic anxieties portrayed in the films Beasts of the Southern Wild, Take iii Shelter, and Melancholia. -

'Post-Los Angeles': the Conceptual City in Steve Erickson's

‘Post-Los Angeles’: The Conceptual City in Steve Erickson’s Amnesiascope Liam Randles antae, Vol. 5, No. 2 (Jun., 2018), 138-153 Proposed Creative Commons Copyright Notices Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following terms: a. Authors retain copyright and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgement of the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal. b. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See The Effect of Open Access). antae (ISSN 2523-2126) is an international refereed postgraduate journal aimed at exploring current issues and debates within English Studies, with a particular interest in literature, criticism and their various contemporary interfaces. Set up in 2013 by postgraduate students in the Department of English at the University of Malta, it welcomes submissions situated across the interdisciplinary spaces provided by diverse forms and expressions within narrative, poetry, theatre, literary theory, cultural criticism, media studies, digital cultures, philosophy and language studies. Creative writing and book reviews are also encouraged submissions. 138 ‘Post-Los Angeles’: The Conceptual City in Steve Erickson’s Amnesiascope Liam Randles University of Liverpool Erickson’s Conceptual Settings A striking hallmark of Steve Erickson’s fiction—that is, the author’s conceptualisation of setting in order to highlight an environment’s transformative qualities—can be traced from a dual position of personal experience and literary influence. -

1 Anthology: the Blurbs of Thomas Pynchon Compiled by Patrick Lane

Anthology: The Blurbs of Thomas Pynchon Compiled by Patrick Lane from Post Road 14 Selected by Wesley Stace, author of by George and Misfortune. Blurbs are almost always besides the point. But I agree with the Neal Pollack. Post Road "feels like it is put out by actual people". I agree with Barry Gifford that it is "a jewel in a bucket of stones". In fact, I'd gladly have nominated the whole of Post Road 14. What other magazine would print Mary Gaitskill's appreciation of Barrie's Peter Pan, next to a reprint of Wilkie Collins' 1863 A Petition to Novel-Writers, a questionnaire answered by George Saunders, a recommendation of the work of William Boyd, and a reproduction of Anais Nin's marriage certificate? And I haven't even scratched the surface - of one issue. Post Road manages to be a fan mail to good writing, and full of good writing itself. It is nostalgia for then and passion for now all rolled into one attractive package. It's unafraid to give airtime to private passions. It lets me opine enthusiastically about the abnormal romances of J. Meade Falkner: it was by no means certain that anyone would ever ask. It's the right size. It collects all Pynchon's blurbs - his most consistent public statements in the nearly 50 year arc of his writing career - so I don't have to. Post Road loves the world of letters. And I love Post Road. – WS. 1 Thomas Pynchon is the author of V., The Crying of Lot 49, Gravity's Rainbow, Slow Learner, a collection of short stories, Vineland, Mason & Dixon and, most recently, Against the Day. -

Staging Delillo

Staging DeLillo Rebecca Rey B.A. (Hons), The University of Western Australia, 2006 10322929 This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Social and Cultural Studies Discipline of English and Cultural Studies 2012 Abstract This thesis examines the plays of Don DeLillo. Although DeLillo‘s novels have received much critical discussion, his theatre works, with a few exceptions, have been largely ignored in literary circles. This thesis focuses on DeLillo‘s plays to rectify, in part, the lack of scholarship on this topic. In what follows I will examine each of DeLillo‘s six playtexts in chronological order, devoting a chapter to each of his main plays. Common themes emerging across the oeuvre are the centrality of language, the human fear of death, the elusiveness of truth, and the deception of personal identity. In order to provide a comprehensive critical analysis of DeLillo‘s plays, I will draw on a wide range of sources, including DeLillo‘s novels, personal notes and correspondence, interviews with the writer, and theatre performance reviews, in order to reach a better critical understanding of DeLillo‘s plays. This unprecedented examination of DeLillo‘s plays contributes not only to a deeper understanding of his other fictional works, but is rewarding in itself, as the plays can stand alone as being worthy of critical attention. In Chapter 1, I present an analysis of DeLillo‘s ‗The Engineer of Moonlight‘ (1979)—his first published, but as yet unperformed, playtext. ‗The Engineer‘ bears striking similarities in theme with DeLillo‘s earlier novel Ratner’s Star (1976). -

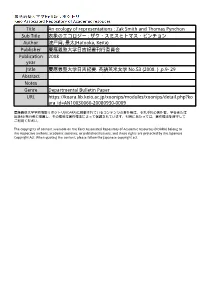

Title an Ecology of Representations : Zak Smith and Thomas Pynchon

Title An ecology of representations : Zak Smith and Thomas Pynchon Sub Title 表象のエコロジー : ザク・スミスとトマス・ピンチョン Author 波戸岡, 景太(Hatooka, Keita) Publisher 慶應義塾大学日吉紀要刊行委員会 Publication 2008 year Jtitle 慶應義塾大学日吉紀要. 英語英米文学 No.53 (2008. ) ,p.9- 29 Abstract Notes Genre Departmental Bulletin Paper URL https://koara.lib.keio.ac.jp/xoonips/modules/xoonips/detail.php?ko ara_id=AN10030060-20080930-0009 慶應義塾大学学術情報リポジトリ(KOARA)に掲載されているコンテンツの著作権は、それぞれの著作者、学会または 出版社/発行者に帰属し、その権利は著作権法によって保護されています。引用にあたっては、著作権法を遵守して ご利用ください。 The copyrights of content available on the KeiO Associated Repository of Academic resources (KOARA) belong to the respective authors, academic societies, or publishers/issuers, and these rights are protected by the Japanese Copyright Act. When quoting the content, please follow the Japanese copyright act. Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) An Ecology of Representations: Zak Smith and Thomas Pynchon Keita Hatooka Laura: […]Mother calls them a glass menagerie! Here’s an example of one, if you’d like to see it! . Oh, be careful—if you breathe, it breaks! . You see how the light shines through him? Jim: It sure does shine! Laura: I shouldn’t be partial, but he is my favorite one. Jim: What kind of a thing is this one supposed to be? Laura: Haven’t you noticed the single horn on his forehead? Jim: A unicorn, huh? —aren’t they extinct in the modern world? Laura: I know! —Tennessee Williams, The Glass Menagerie From one of his earliest short pieces of fi ction, “Entropy” (1960), through to his latest novel Against the Day (2006), Thomas Pynchon’s literary world has been set within the modern world, where not only unicorns, but also dodo birds are extinct.1 Yet perhaps, upon refl ection, it would be more accurate to see this literary creation as placed within the postmodern world where Pynchon’s characters cannot get over the idea that if they had stopped believing, on an epistemological level, in the chronological or theological or scientifi c order of their living world these creatures might have avoided extinction. -

Zak Smith and Thomas Pynchon Sub Title 表象のエコロジー : ザク・スミスとトマス・ピンチョン Author 波戸岡, 景太(Hatooka, Keita) Publisher 慶應義塾大学日吉紀要刊行委員会 Publication 2008 Year Jtitle 慶應義塾大学日吉紀要

Title An ecology of representations : Zak Smith and Thomas Pynchon Sub Title 表象のエコロジー : ザク・スミスとトマス・ピンチョン Author 波戸岡, 景太(Hatooka, Keita) Publisher 慶應義塾大学日吉紀要刊行委員会 Publication 2008 year Jtitle 慶應義塾大学日吉紀要. 英語英米文学 No.53 (2008. ) ,p.9- 29 Abstract Notes Genre Departmental Bulletin Paper URL http://koara.lib.keio.ac.jp/xoonips/modules/xoonips/detail.php?koar a_id=AN10030060-20080930-0009 Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) An Ecology of Representations: Zak Smith and Thomas Pynchon Keita Hatooka Laura: […]Mother calls them a glass menagerie! Here’s an example of one, if you’d like to see it! . Oh, be careful—if you breathe, it breaks! . You see how the light shines through him? Jim: It sure does shine! Laura: I shouldn’t be partial, but he is my favorite one. Jim: What kind of a thing is this one supposed to be? Laura: Haven’t you noticed the single horn on his forehead? Jim: A unicorn, huh? —aren’t they extinct in the modern world? Laura: I know! —Tennessee Williams, The Glass Menagerie From one of his earliest short pieces of fi ction, “Entropy” (1960), through to his latest novel Against the Day (2006), Thomas Pynchon’s literary world has been set within the modern world, where not only unicorns, but also dodo birds are extinct.1 Yet perhaps, upon refl ection, it would be more accurate to see this literary creation as placed within the postmodern world where Pynchon’s characters cannot get over the idea that if they had stopped believing, on an epistemological level, in the chronological or theological or scientifi c order of their living world these creatures might have avoided extinction. -

Transatlantica, 1 | 2016 Fiction Rescues History: Don Delillo Conference in Paris 2

Transatlantica Revue d’études américaines. American Studies Journal 1 | 2016 Modernist Revolutions: American Poetry and the Paradigm of the New Fiction Rescues History: Don DeLillo Conference in Paris Paris Diderot University and Paris Sorbonne University, February 18th – 20th, 2016 Luca Ferrando Battistà, Maud Bougerol, Aliette Ventejoux, Béatrice Pire and Sarah Boulet Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/8181 DOI: 10.4000/transatlantica.8181 ISSN: 1765-2766 Publisher AFEA Electronic reference Luca Ferrando Battistà, Maud Bougerol, Aliette Ventejoux, Béatrice Pire and Sarah Boulet, “Fiction Rescues History: Don DeLillo Conference in Paris”, Transatlantica [Online], 1 | 2016, Online since 04 February 2017, connection on 29 April 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/8181 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/transatlantica.8181 This text was automatically generated on 29 April 2021. Transatlantica – Revue d'études américaines est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Fiction Rescues History: Don DeLillo Conference in Paris 1 Fiction Rescues History: Don DeLillo Conference in Paris Paris Diderot University and Paris Sorbonne University, February 18th – 20th, 2016 Luca Ferrando Battistà, Maud Bougerol, Aliette Ventejoux, Béatrice Pire and Sarah Boulet 1 The Don DeLillo conference which took place in Paris from Thursday, February 18th to Saturday, February 20th, 2016 was a major event graced by the presence of the author himself and prestigious DeLillo scholars, and attended by a numerous audience. It was hosted by Paris Diderot University and Paris Sorbonne University, and organized by Antoine Cazé, Karim Daanoune, Jean-Yves Pellegrin and Anne-Laure Tissut. -

ZEROVILLE by Steve Erickson

ZEROVILLE By Steve Erickson Zeroville beings in 1969 on Hollywood Boulevard, when a Greyhound bus drops off a film-obsessed ex-seminarian with images of Elizabeth Taylor and Montgomery Clift tattooed on his head. Vikar Jerome steps into the vortex of a cultural transformation: rock ‘n’ roll, sex, drugs, and—far more important to him—the decline of the movie studios and the rise of the independent director. Jerome will become a film editor of astonishing vision. Then through encounters with former starlets, burglars, political guerillas, punk musicians, and veteran filmmakers, he discovers the astonishing secret that lies in every movie ever made. DISCUSSION QUESTIONS 1. Erickson employs a very interesting structure, using numbered vignettes increasing and decreasing instead of a more traditional narrative. What is the effect of reading novels with unusual structures? Can you think of other examples of unusually-structured novels that impacted your reading experience? 2. The style of this novel is often surreal or dreamlike. What might this say about the fictional world of film? About the world we live in? 3. Based on characters’ reactions to Vikar’s tattoo, how do you think the general perception of body art has changed over time? What are your thoughts on piercings and tattoos? 4. How did you interpret Vikar’s arrest and interrogation? What, if anything, does it foreshadow? 5. Nomenclature in this novel is quite unusual. What meaning did you attach to characters’ names? Consider Ike “Vikar” Jerome, Viking Man, Soledad Palladin, Zazi, and others. 6. How does Vikar’s past influence his personality and actions? Did you see a change in his character throughout the novel? Discuss. -

I. Capitalism and Schizophrenia in Cosmoposlis

I. Capitalism and Schizophrenia in Cosmoposlis This project focuses on Don Delillo’s Cosmopolis as the discourse of exploration of protagonist’s split subjectivity that is the result of capitalistic infrastructure of the society. Cosmopolis is a novel about a 28 years old multi- billionaire asset manager who makes an odyssey across midtown Manhattan in order to get his hair cut. It explores the dialectics of late capitalism and brings out the evils and vices of capitalistic world in the life of human beings. In the novel Cosmopolis, the protagonist becomes the victim of Laissez-faire capitalism and he meets the catastrophic disaster due to his rationalistic as well as totalitarian philosophy. His material obsession is the cause of his down fall and tragic end. So the project aims to show the evil sides of capitalism of culture industry and proves that material gratification in the contemporary world in the age of capitalism leads towards catastrophic consequences. This research questions the rationalistic philosophy and suggests the need of humanitarian thinking for happy life. This project focuses on the disintegrated family and societal relationship of the character Eric Packer as the cause of late capitalism. This research explores that capitalism creates manufactured risk and there is profound uncertainty in the lives of human beings. In the text Cosmopolis, Don Delillo’s protagonist Eric Packer faces the tragic end because of his material gratification and rationalistic philosophy. In the age of globalization, human beings are Icarian figures like Packer because they desire more and more matters or capitals. Eric Packer lacks humanity, emotions, philanthropic qualities and romantic life due to his totalitarian philosophy. -

Kierkegaard's Reflection in Don Delillo's Novel „Falling Man?

European Journal of Science and Theology, February 2017, Vol.13, No.1, 15-23 _______________________________________________________________________ KIERKEGAARD’S REFLECTION IN DON DELILLO’S NOVEL ‘FALLING MAN’ Martina Pavlíková* Constantine the Philosopher University in Nitra, Faculty of Arts, Central European Research Institute of Søren Kierkegaard, Hodžova 1, 949 74 Nitra, Slovak Republic (Received 7 October 2016) Abstract This paper analyses Don DeLillo‟s novel „Falling Man‟, which is concerned with the symbolic nature of terrorist violence portrayed and interpreted through the mass media that are able to create a specific simulacrum of reality. DeLillo‟s narrative examines the possibilities of reinventing one‟s individual identity and the tendency of individuals to construct their own identities through a group mentality as well. The paper also deals with the influence of the Danish thinker Soren Kierkegaard on the novel „Falling Man‟. Keywords: subjectivity, terrorism, despair, anxiety, hedonism 1. Introduction Don DeLillo (1936) is a very significant American writer, playwright and essayist. He currently belongs among the most phenomenal and important novelists of modern American literary era. Literary critic Harold Bloom “named him as one of the four major American novelists of his time, along with Thomas Pynchon, Philip Roth, and Cormac McCarthy” [1]. He is considered to be a representative of postmodern literature. Don DeLillo himself stresses that he has been profoundly influenced by “abstract expressionism, European movies and jazz” [2]. His unique literary work reflects the concept of man and modern society being impacted by the advances of Science and technology. His novels intertwine modern appliances, scientific technology, mass media, nuclear wars, sport, various forms of art, cultural performances, cultural objects, cold war, digital age, economy, conspiracy theories and global terrorism. -

THE ECSTASY of INFLUENCE a Plagiarism by Jonathan Lethem

C R T C S M THE ECSTASY OF INFLUENCE A plagiarism By Jonathan Lethem All mankind is of one author, and is adopt Lichberg's tale consciously? Or Still: did Nabokov consciously borrow one volume; when one man dies, one did the earlier tale exist for Nabokov as and quote? chapter is not torn out of the book, but a hidden, unacknowledged memory? "When you live outside the law, you translated into a better language; and The history of literature is not without have to eliminate dishonesty." The every chapter must be so translated.... examples of this phenomenon, called line comes from Don Siegel's 1958 film -John Donne cryptomnesia. Another hypothesis is noir, The Lineup, written by Stirling Silliphant. The film still LOVE AND THEFT haunts revival houses, likely thanks to Eli Wallach's blaz- Consider this tale: a cul- ing portrayal of a sociopath- tivated man of middle age ic hit man and to Siegel's looks back on the story of long, sturdy auteurist career. an amour [ou, one beginning Yet what were those words when, traveling abroad, he worth-to Siegel, or Sil- takes a room as a lodger. The liphant, or their audience- moment he sees the daugh- in 1958? And again: what ter of the house, he is lost. was the line worth when Bob She is a preteen, whose Dylan heard it (presumably charms instantly enslave in some Greenwich Village him. Heedless of her age, he repertory cinema), cleaned becomes intimate with her. it up a little, and inserted it In the end she dies, and the into "Absolutely Sweet narrator-marked by her Marie"? What are they worth forever-remains alone.