Identity and Conflict in Posturban Culture a Dissertation Submitted in Partial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

227-Newsletter.Pdf

THE POETRY PROJECT NEWSLETTER www.poetryproject.org APR/MAY 2011 #227 LETTERS POEM NATHANIEL MACKEY INTERVIEW CARLA HARRYMAN & LYN HEJINIAN TALK WITH CORINA COPP CALENDAR PATRICK JAMES DUNAGAN REVIEWS CHAPBOOKS BY ARIEL GOLDBERG, JESSICA FIORINI, JIM CARROLL, ALLI WARREN & NICHOLAS JAMES WHITTINGTON CATHERINE WAGNER REVIEWS ANDREA BRADY CACONRAD REVIEWS SUSIE TIMMONS FARRAH FIELD REVIEWS PAUL LEGAULT CARLEY MOORE REVIEWS EILEEN MYLES ERIK ANDERSON REVIEWS RENEE GLADMAN DAVID BRAZIL REVIEWS MINA PAM DICK STEPHANIE DICKINSON REVIEWS LEWIS WARSH MATT LONGABUCCO REVIEWS MIŁOSZ BIEDRZYCKI JAMIE TOWNSEND REVIEWS PAUL FOSTER JOHNSON ABRAHAM AVNISAN REVIEWS CAROLINE BERGVALL NICOLE TRIGG REVIEWS JULIANA LESLIE ERICA KAUFMAN REVIEWS KARINNE KEITHLEY $5? 02 APR/MAY 11 #227 THE POETRY PROJECT NEWSLETTER NEWSLETTER EDITOR: Corina Copp DISTRIBUTION: Small Press Distribution, 1341 Seventh St., Berkeley, CA 94710 The Poetry Project, Ltd. Staff ARTISTIC DIRECTOR: Stacy Szymaszek PROGRAM COORDINATOR: Arlo Quint PROGRAM ASSISTANT: Nicole Wallace MONDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR: Macgregor Card MONDAY NIGHT TALK SERIES COORDINATOR: Michael Scharf WEDNESDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR: Joanna Fuhrman FRIDAY NIGHT COORDINATORS: Brett Price SOUND TECHNICIAN: David Vogen VIDEOGRAPHER: Alex Abelson BOOKKEEPER: Stephen Rosenthal ARCHIVIST: Will Edmiston BOX OFFICE: Courtney Frederick, Kelly Ginger, Vanessa Garver INTERNS: Nina Freeman, Stephanie Jo Elstro, Rebecca Melnyk VOLUNTEERS: Jim Behrle, Rachel Chatham, Corinne Dekkers, Ivy Johnson, Erica Kaufman, Christine Kelly, Ace McNamara, Annie Paradis, Christa Quint, Judah Rubin, Lauren Russell, Thomas Seely, Erica Wessmann, Alice Whitwham, Dustin Williamson The Poetry Project Newsletter is published four times a year and mailed free of charge to members of and contributors to the Poetry Project. Subscriptions are available for $25/year domestic, $45/year international. -

In BLACK CLOCK, Alaska Quarterly Review, the Rattling Wall and Trop, and She Is Co-Organizer of the Griffith Park Storytelling Series

BLACK CLOCK no. 20 SPRING/SUMMER 2015 2 EDITOR Steve Erickson SENIOR EDITOR Bruce Bauman MANAGING EDITOR Orli Low ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Joe Milazzo PRODUCTION EDITOR Anne-Marie Kinney POETRY EDITOR Arielle Greenberg SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR Emma Kemp ASSOCIATE EDITORS Lauren Artiles • Anna Cruze • Regine Darius • Mychal Schillaci • T.M. Semrad EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Quinn Gancedo • Jonathan Goodnick • Lauren Schmidt Jasmine Stein • Daniel Warren • Jacqueline Young COMMUNICATIONS EDITOR Chrysanthe Tan SUBMISSIONS COORDINATOR Adriana Widdoes ROVING GENIUSES AND EDITORS-AT-LARGE Anthony Miller • Dwayne Moser • David L. Ulin ART DIRECTOR Ophelia Chong COVER PHOTO Tom Martinelli AD DIRECTOR Patrick Benjamin GUIDING LIGHT AND VISIONARY Gail Swanlund FOUNDING FATHER Jon Wagner Black Clock © 2015 California Institute of the Arts Black Clock: ISBN: 978-0-9836625-8-7 Black Clock is published semi-annually under cover of night by the MFA Creative Writing Program at the California Institute of the Arts, 24700 McBean Parkway, Valencia CA 91355 THANK YOU TO THE ROSENTHAL FAMILY FOUNDATION FOR ITS GENEROUS SUPPORT Issues can be purchased at blackclock.org Editorial email: [email protected] Distributed through Ingram, Ingram International, Bertrams, Gardners and Trust Media. Printed by Lightning Source 3 Norman Dubie The Doorbell as Fiction Howard Hampton Field Trips to Mars (Psychedelic Flashbacks, With Scones and Jam) Jon Savage The Third Eye Jerry Burgan with Alan Rifkin Wounds to Bind Kyra Simone Photo Album Ann Powers The Sound of Free Love Claire -

I PRACTICAL MAGIC: MAGICAL REALISM and the POSSIBILITIES

i PRACTICAL MAGIC: MAGICAL REALISM AND THE POSSIBILITIES OF REPRESENTATION IN TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY FICTION AND FILM by RACHAEL MARIBOHO DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington August, 2016 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Wendy B. Faris, Supervising Professor Neill Matheson Kenneth Roemer Johanna Smith ii ABSTRACT: Practical Magic: Magical Realism And The Possibilities of Representation In Twenty-First Century Fiction And Film Rachael Mariboho, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2016 Supervising Professor: Wendy B. Faris Reflecting the paradoxical nature of its title, magical realism is a complicated term to define and to apply to works of art. Some writers and critics argue that classifying texts as magical realism essentializes and exoticizes works by marginalized authors from the latter part of the twentieth-century, particularly Latin American and postcolonial writers, while others consider magical realism to be nothing more than a marketing label used by publishers. These criticisms along with conflicting definitions of the term have made classifying contemporary works that employ techniques of magical realism a challenge. My dissertation counters these criticisms by elucidating the value of magical realism as a narrative mode in the twenty-first century and underlining how magical realism has become an appealing means for representing contemporary anxieties in popular culture. To this end, I analyze how the characteristics of magical realism are used in a select group of novels and films in order to demonstrate the continued significance of the genre in modern art. I compare works from Tea Obreht and Haruki Murakami, examine the depiction of adolescent females in young adult literature, and discuss the environmental and apocalyptic anxieties portrayed in the films Beasts of the Southern Wild, Take iii Shelter, and Melancholia. -

'Post-Los Angeles': the Conceptual City in Steve Erickson's

‘Post-Los Angeles’: The Conceptual City in Steve Erickson’s Amnesiascope Liam Randles antae, Vol. 5, No. 2 (Jun., 2018), 138-153 Proposed Creative Commons Copyright Notices Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following terms: a. Authors retain copyright and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgement of the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal. b. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See The Effect of Open Access). antae (ISSN 2523-2126) is an international refereed postgraduate journal aimed at exploring current issues and debates within English Studies, with a particular interest in literature, criticism and their various contemporary interfaces. Set up in 2013 by postgraduate students in the Department of English at the University of Malta, it welcomes submissions situated across the interdisciplinary spaces provided by diverse forms and expressions within narrative, poetry, theatre, literary theory, cultural criticism, media studies, digital cultures, philosophy and language studies. Creative writing and book reviews are also encouraged submissions. 138 ‘Post-Los Angeles’: The Conceptual City in Steve Erickson’s Amnesiascope Liam Randles University of Liverpool Erickson’s Conceptual Settings A striking hallmark of Steve Erickson’s fiction—that is, the author’s conceptualisation of setting in order to highlight an environment’s transformative qualities—can be traced from a dual position of personal experience and literary influence. -

1 Anthology: the Blurbs of Thomas Pynchon Compiled by Patrick Lane

Anthology: The Blurbs of Thomas Pynchon Compiled by Patrick Lane from Post Road 14 Selected by Wesley Stace, author of by George and Misfortune. Blurbs are almost always besides the point. But I agree with the Neal Pollack. Post Road "feels like it is put out by actual people". I agree with Barry Gifford that it is "a jewel in a bucket of stones". In fact, I'd gladly have nominated the whole of Post Road 14. What other magazine would print Mary Gaitskill's appreciation of Barrie's Peter Pan, next to a reprint of Wilkie Collins' 1863 A Petition to Novel-Writers, a questionnaire answered by George Saunders, a recommendation of the work of William Boyd, and a reproduction of Anais Nin's marriage certificate? And I haven't even scratched the surface - of one issue. Post Road manages to be a fan mail to good writing, and full of good writing itself. It is nostalgia for then and passion for now all rolled into one attractive package. It's unafraid to give airtime to private passions. It lets me opine enthusiastically about the abnormal romances of J. Meade Falkner: it was by no means certain that anyone would ever ask. It's the right size. It collects all Pynchon's blurbs - his most consistent public statements in the nearly 50 year arc of his writing career - so I don't have to. Post Road loves the world of letters. And I love Post Road. – WS. 1 Thomas Pynchon is the author of V., The Crying of Lot 49, Gravity's Rainbow, Slow Learner, a collection of short stories, Vineland, Mason & Dixon and, most recently, Against the Day. -

American Book Awards 2004

BEFORE COLUMBUS FOUNDATION PRESENTS THE AMERICAN BOOK AWARDS 2004 America was intended to be a place where freedom from discrimination was the means by which equality was achieved. Today, American culture THE is the most diverse ever on the face of this earth. Recognizing literary excel- lence demands a panoramic perspective. A narrow view strictly to the mainstream ignores all the tributaries that feed it. American literature is AMERICAN not one tradition but all traditions. From those who have been here for thousands of years to the most recent immigrants, we are all contributing to American culture. We are all being translated into a new language. BOOK Everyone should know by now that Columbus did not “discover” America. Rather, we are all still discovering America—and we must continue to do AWARDS so. The Before Columbus Foundation was founded in 1976 as a nonprofit educational and service organization dedicated to the promotion and dissemination of contemporary American multicultural literature. The goals of BCF are to provide recognition and a wider audience for the wealth of cultural and ethnic diversity that constitutes American writing. BCF has always employed the term “multicultural” not as a description of an aspect of American literature, but as a definition of all American litera- ture. BCF believes that the ingredients of America’s so-called “melting pot” are not only distinct, but integral to the unique constitution of American Culture—the whole comprises the parts. In 1978, the Board of Directors of BCF (authors, editors, and publishers representing the multicultural diversity of American Literature) decided that one of its programs should be a book award that would, for the first time, respect and honor excellence in American literature without restric- tion or bias with regard to race, sex, creed, cultural origin, size of press or ad budget, or even genre. -

Magic Capitalism and Melodramatic Imagination—Producing Locality and Reconstructing Asian Ethnicity in Karen Tei Yamashita’S Through the Arc of the Rain Forest*

EURAMERICA Vol. 34, No. 4 (December 2004), 587-625 © Institute of European and American Studies, Academia Sinica Magic Capitalism and Melodramatic Imagination—Producing Locality and Reconstructing Asian Ethnicity in Karen Tei Yamashita’s Through the Arc of the Rain Forest* Shu-ching Chen Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures Chung-Hsing University E-Mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper investigates the production of locality in Karen Tei Yamashita’s Through the Arc of the Rain Forest (1990). The production of locality as dramatized by the novel consists of two phases of local spatialization in the context of time-space compression: deterritorialization and reterritorialization. Yamashita employs a specific narrative style that wavers between magic realism and melodrama to address the uncertainty, rupture, and incongruity derived from the condition in which transnational capitalism exerts both negative and positive impacts on local places in the Received October 23, 2003; accepted June 10, 2004; last revised July 23, 2004 Proofreaders: Jin-shiou Lin, Kuei-feng Hu * The completion of this article was made possible by a research grant provided by National Science Council (NSC-91-2411-H-005-003). I am much obliged to the generosity of NSC. I also want to express my gratitude to my research assistants, Yi-ting Luo and Shu-hong Liu for their ardent help in all aspects of the project. The generous and insightful comments from two anonymous reviewers help me trim out the redundant details to give the article a clear contour. I appreciate their time and attention for an underpaid job that is crucial for elevating academic expertise. -

Traveling the Distances of Karen Tei Yamashita's Fiction

Asian American Literature: Discourses and Pedagogies 1 (2010) 6-15. Traveling the Distances of Karen Tei Yamashita’s Fiction: A Review Essay on Yamashita Scholarship and Transnational Studies By Pamela Thoma It is a particular story that must be placed in its particular time and place. It is a work of fiction, and the characters are also works of fiction. Certainly it cannot be construed to be representative of that enormous and diverse community of which it is but a part. And yet, perhaps, here is a story that belongs to all of us who travel distances to find something that is, after all, home. Karen Tei Yamashita, Brazil-Maru, frontispiece Karen Tei Yamashita’s sophisticated prose texts, including Through the Arc of the Rainforest (1990), Brazil-Maru (1992), Tropic of Orange (1997), and Circle K Cycles (2001), encompass a vast range of narratives styles and genres.1 Individually and collectively, they also present multiple perspectives and points of view, contemporary contexts and historical connections, physical and psychic distances. A vision with this scope can be a challenge for critics to navigate, and it can compel new critical approaches and intellectual paradigms, which is precisely the case in Yamashita scholarship. By focusing on issues associated with globalization, which recur throughout the texts, scholars are able to trace the great distances traversed through Yamashita’s work. These issues include global economic policies and inequalities, the migration of people, cultural flows and consumer culture, information and digital technology (i.e. “informatics”) or new types of knowledge, global ecology, the dynamic borders of nation-states, and the re-organization of community. -

Divercity – Global Cities As a Literary Phenomenon

Melanie U. Pooch DiverCity – Global Cities as a Literary Phenomenon Lettre Melanie U. Pooch received her doctoral degree at the University of Mannheim, Germany. Her research interests include Corporate Responsibility and North American cultural, urban, and literary studies in a globalizing age. Melanie U. Pooch DiverCity – Global Cities as a Literary Phenomenon Toronto, New York, and Los Angeles in a Globalizing Age The original version of this manuscript was submitted as a doctoral dissertation to the University of Mannheim. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Natio- nalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de © 2016 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or uti- lized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover layout: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Cover illustration: New York City 2007 by Michela Zangiacomi Busch, Sulz- burg; © M.U. Pooch Printed in Germany Print-ISBN 978-3-8376-3541-6 PDF-ISBN 978-3-8394-3541-0 Contents Acknowledgements | 7 1 Introduction | 9 2 Globalization and Its Effects | 15 2.1 Mapping Globalization | 15 2.2 Global Consensus | 18 2.3 Global Controversies | 23 3 Global Cities as Cultural Nodal Points -

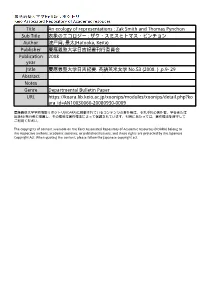

Title an Ecology of Representations : Zak Smith and Thomas Pynchon

Title An ecology of representations : Zak Smith and Thomas Pynchon Sub Title 表象のエコロジー : ザク・スミスとトマス・ピンチョン Author 波戸岡, 景太(Hatooka, Keita) Publisher 慶應義塾大学日吉紀要刊行委員会 Publication 2008 year Jtitle 慶應義塾大学日吉紀要. 英語英米文学 No.53 (2008. ) ,p.9- 29 Abstract Notes Genre Departmental Bulletin Paper URL https://koara.lib.keio.ac.jp/xoonips/modules/xoonips/detail.php?ko ara_id=AN10030060-20080930-0009 慶應義塾大学学術情報リポジトリ(KOARA)に掲載されているコンテンツの著作権は、それぞれの著作者、学会または 出版社/発行者に帰属し、その権利は著作権法によって保護されています。引用にあたっては、著作権法を遵守して ご利用ください。 The copyrights of content available on the KeiO Associated Repository of Academic resources (KOARA) belong to the respective authors, academic societies, or publishers/issuers, and these rights are protected by the Japanese Copyright Act. When quoting the content, please follow the Japanese copyright act. Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) An Ecology of Representations: Zak Smith and Thomas Pynchon Keita Hatooka Laura: […]Mother calls them a glass menagerie! Here’s an example of one, if you’d like to see it! . Oh, be careful—if you breathe, it breaks! . You see how the light shines through him? Jim: It sure does shine! Laura: I shouldn’t be partial, but he is my favorite one. Jim: What kind of a thing is this one supposed to be? Laura: Haven’t you noticed the single horn on his forehead? Jim: A unicorn, huh? —aren’t they extinct in the modern world? Laura: I know! —Tennessee Williams, The Glass Menagerie From one of his earliest short pieces of fi ction, “Entropy” (1960), through to his latest novel Against the Day (2006), Thomas Pynchon’s literary world has been set within the modern world, where not only unicorns, but also dodo birds are extinct.1 Yet perhaps, upon refl ection, it would be more accurate to see this literary creation as placed within the postmodern world where Pynchon’s characters cannot get over the idea that if they had stopped believing, on an epistemological level, in the chronological or theological or scientifi c order of their living world these creatures might have avoided extinction. -

27Th Annual Conference on American Literature May 26-29, 2016

American Literature Association A Coalition of Societies Devoted to the Study of American Authors 27th Annual Conference on American Literature May 26-29, 2016 Hyatt Regency San Francisco in Embarcadero Center 5 Embarcadero Center San Francisco CA 94111 415-788-1234 Conference Director Alfred Bendixen, Princeton University Registration Desk (Pacific Concourse): Wednesday, 8:00 pm – 10:00 pm; Thursday, 7:30 am - 5:30 pm; Friday, 7:30 am - 5:00 pm; Saturday, 7:30 am - 3:00 pm; Sunday, 8:00 am - 10:30 am. Book Exhibits (Pacific L-M-N-0): Thursday: Noon-5 pm; Friday, 9 am – 5 pm; Saturday, 9 am – 3 pm. Exhibitor Set-up: Thursday 8:00 am -Noon All meeting rooms are either on the Pacific Concourse or Bay Level 1 Acknowledgements: I would like to thank all of the society representatives and the panelists for their contributions to the conference. I owe special thanks to the three Executive Coordinators of the American Literature Association who have sustained me and this organization with many years of good counsel and warm friendship: Gloria Cronin, Olivia Carr Edenfield, and James Nagel. Rene H. Trevino has also provided exceptional service in his role of ALA webmaster. I want to offer special thanks and appreciation to The Department of Literature and Philosophy at Georgia Southern University for its ongoing support of this conference and all of the activities of the American Literature Association. I also want to express my appreciation for the professional assistance of Georgia Southern University graduate students Christopher Blackburn and Benjamin Peyton. And special thanks to my wife and partner, Judith Hamera, for many years of advice, wisdom, patience, and love. -

Zak Smith and Thomas Pynchon Sub Title 表象のエコロジー : ザク・スミスとトマス・ピンチョン Author 波戸岡, 景太(Hatooka, Keita) Publisher 慶應義塾大学日吉紀要刊行委員会 Publication 2008 Year Jtitle 慶應義塾大学日吉紀要

Title An ecology of representations : Zak Smith and Thomas Pynchon Sub Title 表象のエコロジー : ザク・スミスとトマス・ピンチョン Author 波戸岡, 景太(Hatooka, Keita) Publisher 慶應義塾大学日吉紀要刊行委員会 Publication 2008 year Jtitle 慶應義塾大学日吉紀要. 英語英米文学 No.53 (2008. ) ,p.9- 29 Abstract Notes Genre Departmental Bulletin Paper URL http://koara.lib.keio.ac.jp/xoonips/modules/xoonips/detail.php?koar a_id=AN10030060-20080930-0009 Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) An Ecology of Representations: Zak Smith and Thomas Pynchon Keita Hatooka Laura: […]Mother calls them a glass menagerie! Here’s an example of one, if you’d like to see it! . Oh, be careful—if you breathe, it breaks! . You see how the light shines through him? Jim: It sure does shine! Laura: I shouldn’t be partial, but he is my favorite one. Jim: What kind of a thing is this one supposed to be? Laura: Haven’t you noticed the single horn on his forehead? Jim: A unicorn, huh? —aren’t they extinct in the modern world? Laura: I know! —Tennessee Williams, The Glass Menagerie From one of his earliest short pieces of fi ction, “Entropy” (1960), through to his latest novel Against the Day (2006), Thomas Pynchon’s literary world has been set within the modern world, where not only unicorns, but also dodo birds are extinct.1 Yet perhaps, upon refl ection, it would be more accurate to see this literary creation as placed within the postmodern world where Pynchon’s characters cannot get over the idea that if they had stopped believing, on an epistemological level, in the chronological or theological or scientifi c order of their living world these creatures might have avoided extinction.