Msm Philharmonia Orchestra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nutcracker Three Hundred Sixty-Seventh Program of the 2012-13 Season ______Indiana University Ballet Theater Presents

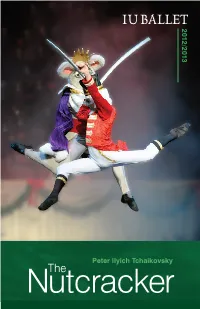

2012/2013 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky NutcrackerThe Three Hundred Sixty-Seventh Program of the 2012-13 Season _______________________ Indiana University Ballet Theater presents its 54th annual production of Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker Ballet in Two Acts Scenario by Michael Vernon, after Marius Petipa’s adaptation of the story, “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” by E. T. A. Hoffmann Michael Vernon, Choreography Andrea Quinn, Conductor C. David Higgins, Set and Costume Designer Patrick Mero, Lighting Designer Gregory J. Geehern, Chorus Master The Nutcracker was first performed at the Maryinsky Theatre of St. Petersburg on December 18, 1892. _________________ Musical Arts Center Friday Evening, November Thirtieth, Eight O’Clock Saturday Afternoon, December First, Two O’Clock Saturday Evening, December First, Eight O’Clock Sunday Afternoon, December Second, Two O’Clock music.indiana.edu The Nutcracker Michael Vernon, Artistic Director Choreography by Michael Vernon Doricha Sales, Ballet Mistress Guoping Wang, Ballet Master Shawn Stevens, Ballet Mistress Phillip Broomhead, Guest Coach Doricha Sales, Children’s Ballet Mistress The children in The Nutcracker are from the Jacobs School of Music’s Pre-College Ballet Program. Act I Party Scene (In order of appearance) Urchins . Chloe Dekydtspotter and David Baumann Passersby . Emily Parker with Sophie Scheiber and Azro Akimoto (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Maura Bell with Eve Brooks and Simon Brooks (Dec. 1 mat. & Dec. 2) Maids. .Bethany Green and Liara Lovett (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Carly Hammond and Melissa Meng (Dec. 1 mat. & Dec. 2) Tradesperson . Shaina Rovenstine Herr Drosselmeyer . .Matthew Rusk (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Gregory Tyndall (Dec. 1 mat.) Iver Johnson (Dec. -

The Evolution of Musical Theatre Dance

Gordon 1 Jessica Gordon 29 March 2010 Honors Thesis Everything was Beautiful at the Ballet: The Evolution of Musical Theatre Dance During the mid-1860s, a ballet troupe from Paris was brought to the Academy of Music in lower Manhattan. Before the company’s first performance, however, the theatre in which they were to dance was destroyed in a fire. Nearby, producer William Wheatley was preparing to begin performances of The Black Crook, a melodrama with music by Charles M. Barras. Seeing an opportunity, Wheatley conceived the idea to combine his play and the displaced dance company, mixing drama and spectacle on one stage. On September 12, 1866, The Black Crook opened at Niblo’s Gardens and was an immediate sensation. Wheatley had unknowingly created a new American art form that would become a tradition for years to come. Since the first performance of The Black Crook, dance has played an important role in musical theatre. From the dream ballet in Oklahoma to the “Dance at the Gym” in West Side Story to modern shows such as Movin’ Out, dance has helped tell stories and engage audiences throughout musical theatre history. Dance has not always been as integrated in musicals as it tends to be today. I plan to examine the moments in history during which the role of dance on the Broadway stage changed and how those changes affected the manner in which dance is used on stage today. Additionally, I will discuss the important choreographers who have helped develop the musical theatre dance styles and traditions. As previously mentioned, theatrical dance in America began with the integration of European classical ballet and American melodrama. -

Twyla Tharp Th Anniversary Tour

Friday, October 16, 2015, 8pm Saturday, October 17, 2015, 8pm Sunday, October 18, 2015, 3pm Zellerbach Hall Twyla Tharp D?th Anniversary Tour r o d a n a f A n e v u R Daniel Baker, Ramona Kelley, Nicholas Coppula, and Eva Trapp in Preludes and Fugues Choreography by Twyla Tharp Costumes and Scenics by Santo Loquasto Lighting by James F. Ingalls The Company John Selya Rika Okamoto Matthew Dibble Ron Todorowski Daniel Baker Amy Ruggiero Ramona Kelley Nicholas Coppula Eva Trapp Savannah Lowery Reed Tankersley Kaitlyn Gilliland Eric Otto These performances are made possible, in part, by an Anonymous Patron Sponsor and by Patron Sponsors Lynn Feintech and Anthony Bernhardt, Rockridge Market Hall, and Gail and Daniel Rubinfeld. Cal Performances’ – season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. PROGRAM Twyla Tharp D?th Anniversary Tour “Simply put, Preludes and Fugues is the world as it ought to be, Yowzie as it is. The Fanfares celebrate both.”—Twyla Tharp, 2015 PROGRAM First Fanfare Choreography Twyla Tharp Music John Zorn Musical Performers The Practical Trumpet Society Costumes Santo Loquasto Lighting James F. Ingalls Dancers The Company Antiphonal Fanfare for the Great Hall by John Zorn. Used by arrangement with Hips Road. PAUSE Preludes and Fugues Dedicated to Richard Burke (Bay Area première) Choreography Twyla Tharp Music Johann Sebastian Bach Musical Performers David Korevaar and Angela Hewitt Costumes Santo Loquasto Lighting James F. Ingalls Dancers The Company The Well-Tempered Clavier : Volume 1 recorded by MSR Records; Volume 2 recorded by Hyperi on Records Ltd. INTERMISSION PLAYBILL PROGRAM Second Fanfare Choreography Twyla Tharp Music John Zorn Musical Performers American Brass Quintet Costumes Santo Loquasto Lighting James F. -

Eating Disorders in Korea

SNU THE SNU QUILL VOLUME 66 VOLUME DEC 17 FROM THE EDITOR I was outside a bookstore the other day when I saw this small boy run up to his sister and hit her in the face. He was yelling something at her, something indistinguishable because EDITOR-IN-CHIEF of the snot running down his nose, but I gathered that she had taken something from him. John Kim She responded to his provocation in a pretty reasonable way: she slapped him so hard he spun, then fell on the floor, screaming.The screaming made their parents turn around, see their older daughter with her hand outstretched in a brilliant forehand follow-through, and their SECTION EDITORS son on the floor, crying. The mom rushed over and picked up the boy and shushed him and told him to stop crying and that it was okay. The dad turned back around to his parents and Rakel Solli shrugged halfheartedly, and the three of them just sort of rolled their eyes. All throughout Yeji Kim this process, you could see on the girl’s face that she knew exactly what was coming. And sure Sylvia Yang enough, as soon as her brother stopped crying, the mom went over to the girl and told her with this deadly frozen voice that she shouldn’t bother rejoining the family until she realized how she was supposed to act in public. Then she went off to join her husband and her son CREATIVE DIRECTOR and his grandparents and they all walked away together, without her. The girl stood there for a while, her back turned to me, then ran to catch up with them. -

Twyla Tharp Goes Back to the Bones

HARVARD SQUARED ture” through enchanting light displays, The 109th Annual dramatizes the true story of six-time world decorations, and botanical forms. Kids are Christmas Carol Services champion boxer Emile Griffith, from his welcome; drinks and treats will be available. www.memorialchurch.harvard.edu early days in the Virgin Islands to the piv- (November 24-December 30) The oldest such services in the country otal Madison Square Garden face-off. feature the Harvard University Choir. (November 16- Decem ber 22) Harvard Wind Ensemble Memorial Church. (December 9 and 11) https://harvardwe.fas.harvard.edu FILM The student group performs its annual Hol- The Christmas Revels Harvard Film Archive iday Concert. Lowell Lecture Hall. www.revels.org www.hcl.harvard.edu/hfa (November 30) A Finnish epic poem, The Kalevala, guides “A On Performance, and Other Cultural Nordic Celebration of the Winter Sol- Rituals: Three Films By Valeska Grise- Harvard Glee Club and Radcliffe stice.” Sanders Theatre. (December 14-29) bach. The director is considered part of Choral Society the Berlin School, a contemporary move- www.harvardgleeclub.org THEATER ment focused on intimate realities of rela- The celebrated singers join forces for Huntington Theatre Company tionships. She is on campus as a visiting art- Christmas in First Church. First Church www.huntingtontheatre.org ist to present and discuss her work. in Cambridge. (December 7) Man in the Ring, by Michael Christofer, (November 17-19) STAFF PICK:Twyla Tharp Goes music of Billy Joel), and, in 2012, the ballet based on George MacDonald’s eponymous tale The Princess and the Goblin. Back to the Bones Yet “Minimalism and Me” takes the audience back to New York City in the ‘60s and ‘70s, and the emergence of a rigor- Renowned choreographer Twyla Tharp, Ar.D. -

Constructing the Archive: an Annotated Catalogue of the Deon Van Der Walt

(De)constructing the archive: An annotated catalogue of the Deon van der Walt Collection in the NMMU Library Frederick Jacobus Buys January 2014 Submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Master of Music (Performing Arts) at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Supervisor: Prof Zelda Potgieter TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DECLARATION i ABSTRACT ii OPSOMMING iii KEY WORDS iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION TO THIS STUDY 1 1. Aim of the research 1 2. Context & Rationale 2 3. Outlay of Chapters 4 CHAPTER 2 - (DE)CONSTRUCTING THE ARCHIVE: A BRIEF LITERATURE REVIEW 5 CHAPTER 3 - DEON VAN DER WALT: A LIFE CUT SHORT 9 CHAPTER 4 - THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION: AN ANNOTATED CATALOGUE 12 CHAPTER 5 - CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 18 1. The current state of the Deon van der Walt Collection 18 2. Suggestions and recommendations for the future of the Deon van der Walt Collection 21 SOURCES 24 APPENDIX A PERFORMANCE AND RECORDING LIST 29 APPEDIX B ANNOTED CATALOGUE OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION 41 APPENDIX C NELSON MANDELA METROPOLITAN UNIVERSTITY LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SERVICES (NMMU LIS) - CIRCULATION OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT (DVW) COLLECTION (DONATION) 280 APPENDIX D PAPER DELIVERED BY ZELDA POTGIETER AT THE OFFICIAL OPENING OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION, SOUTH CAMPUS LIBRARY, NMMU, ON 20 SEPTEMBER 2007 282 i DECLARATION I, Frederick Jacobus Buys (student no. 211267325), hereby declare that this treatise, in partial fulfilment for the degree M.Mus (Performing Arts), is my own work and that it has not previously been submitted for assessment or completion of any postgraduate qualification to another University or for another qualification. -

MARK MORRIS DANCE GROUP and MUSIC ENSEMBLE Wed, Mar 30, 7:30 Pm Carlson Family Stage

2015 // 16 SEASON Northrop Presents MARK MORRIS DANCE GROUP AND MUSIC ENSEMBLE Wed, Mar 30, 7:30 pm Carlson Family Stage DIDO AND AENEAS Dear Friends of Northrop, Northrop at the University of Minnesota Presents I count myself lucky that I’ve been able to see a number of Mark Morris Dance Group’s performances over the years—a couple of them here at Northrop in the 90s, and many more in New York as far back as the 80s and as recently as last MARK MORRIS year. Aside from the shocking realization of how quickly time flies, I also realized that the reason I am so eager to see Mark Morris’ work is because it always leaves me with a feeling of DANCE GROUP joy and exhilaration. CHELSEA ACREE SAM BLACK DURELL R. COMEDY* RITA DONAHUE With a definite flair for the theatrical, and a marvelous ability DOMINGO ESTRADA, JR. LESLEY GARRISON LAUREN GRANT BRIAN LAWSON to tell a story through movement, Mark Morris has always AARON LOUX LAUREL LYNCH STACY MARTORANA DALLAS McMURRAY been able to make an audience laugh. While most refer to BRANDON RANDOLPH NICOLE SABELLA BILLY SMITH his “delicious wit,” others found his humor outrageous, and NOAH VINSON JENN WEDDEL MICHELLE YARD he earned a reputation as “the bad boy of modern dance.” *apprentice But, as New York Magazine points out, “Like Martha Graham, Merce Cunningham, Paul Taylor, and Twyla Tharp, Morris has Christine Tschida. Photo by Patrick O'Leary, gone from insurgent to icon.” MARK MORRIS, conductor University of Minnesota. The journey probably started when he was eight years old, MMDG MUSIC ENSEMBLE saw a performance by José Greco, and decided to become a Spanish dancer. -

The New Hampshire, Vol. 69, No. 18

,,............ ~m.pshire Volume 69 Number 18 Durham, N.H. Proposed rule change draws students'. fire By Rosalie H. Davis this for years. It has been the Student lTovernment leaders backbone of .(Student> Caucus. yesterday criticized a proposal That is the one thing that you can limiting their power to allocate point to and say 'This is what Student Activity Tax money. Caucus does,' " Beckingham said. The propQ_sal, dated Oct. 27, Bill Corson, chairman of the was submitted to student Caucus, said that the new clause organization presidents _for concerning SAT monies removes review by Jeff Onore, chairman direct jurisdiction from students of the Student Organizations and places it in administrators' Committee, and calls for SAT hands. organizations to gain approval of "But," Corson said, ' "this funding from the Student Ac proposal is just a first draft. tivities Office, and the Student J.Gregg <Sanborn) said that it Organizations Committee, two isn't cast in granite. The meeting non-student groups. on the 15th will gauge reaction to The present system allows SAT the proposal better than we can groups to have fundi~ allocated right now," he said. directly by the Student Caucus. The proposal will be discussed Jay Beckingham, Student at an open hearing that SAT Government vice president for organiz~tion presidents have commuter affairs, said he was been invited to attend on Nov. 15. insulted by the proposal's clause Both Onore and Sanborn, the (11.13(s)) which changes the director of Student Affairs, were method of approving the SAT attending a conference in Hyan funds. According to Beckingham, nis, Mass. -

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater

Tuesday through Friday, April 10 –13, 2018, 8pm Saturday, April 14, 2018, 2pm and 8pm Sunday, April 15, 2018, 3pm Zellerbach Hall Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater Alvin Ailey, Founder Judith Jamison, Artistic Director Emerita Robert Battle , Artistic Director Masazumi Chaya, Associate Artistic Director CompAny memBeRs Hope Boykin Jacquelin Harris Akua Noni Parker Jeroboam Bozeman Collin Heyward Danica Paulos Clifton Brown Michael Jackson, Jr. Belén Pereyra-Alem Sean Aaron Carmon Megan Jakel Jamar Roberts Sarah Daley-Perdomo Yannick Lebrun Samuel Lee Roberts Ghrai DeVore Renaldo Maurice Kanji Segawa Solomon Dumas Ashley Mayeux Glenn Allen Sims Samantha Figgins Michael Francis McBride Linda Celeste Sims Vernard J. Gilmore Rachael McLaren Constance Stamatiou Jacqueline Green Chalvar Monteiro Jermaine Terry Daniel Harder Fana Tesfagiorgis Matthew Rushing, Rehearsal Director and Guest Artist Bennett Rink, Executive Director Major funding is provided by the National Endowment for the Arts; the New York State Council on the Arts; the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs; American Express; Bank of America; BET Networks; Bloomberg Philanthropies; BNY Mellon; Delta Air Lines; Diageo, North America; Doris Duke Charitable Foundation; FedEx; Ford Foundation; Howard Gilman Foundation; The William R. Kenan, Jr. Charitable Trust; The Prudential Foundation; The SHS Foundation; The Shubert Foundation; Southern Company; Target; The Wallace Foundation; and Wells Fargo. Cal Performances’ 2017 –18 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. pRoGRAm A k -

1984 Category Artist(S)

1984 Category Artist(s) Artist/Title Of Work Venue Choreographer/Creator Anne Bogart South Pacific NYU Experimental Theatear Wing Eiko & Koma Grain/Night Tide DTW Fred Holland/Ishmael Cowboys, Dreams, and Ladders The Kitchen Houston Jones Julia Heyward No Local Stops Ohio Space Mark Morris Season DTW Nina Wiener Wind Devil BAM Stephanie Skura It's Either Now or Later/Art Business DTW, P.S. 122 Timothy Buckley Barn Fever The Kitchen Yoshiko Chuma and the Collective Work School of Hard Knocks Composer Anthony Davis Molissa Fenley/Hempshires BAM Lenny Pickett Stephen Pertronio/Adrift (With Clifford Danspace Project Arnell) Film & TV/Choreographer Frank Moore & Jim Self Beehive Nancy Mason Hauser & Dance Television Workshop at WGBH- Susan Dowling TV Lighting Designer Beverly Emmons Sustained Achievement Carol Mulins Body of Work Danspace Project Jennifer Tipton Sustained Achievement Performer Chuck Greene Sweet Saturday Night (Special Citation) BAM John McLaughlin Douglas Dunn/ Diane Frank/ Deborah Riley Pina Bausch and the 1980 (Special Citation) BAM Wuppertaler Tanztheatre Rob Besserer Lar Lubovitch and Others Sara Rudner Twyla Tharp Steven Humphrey Garth Fagan Valda Setterfield David Gordon Special Achievement/Citations Studies Project of Movement Research, Inc./ Mary Overlie, Wendell Beavers, Renee Rockoff David Gordon Framework/ The Photographer/ DTW, BAM Sustained Achievement Trisha Brown Set and Reset/ Sustained Achievement BAM Visual Designer Judy Pfaff Nina Wiener/Wind Devil Power Boothe Charles Moulton/ Variety Show; David DTW, The Joyce Gordon/ Framework 1985 Category Artist(s) Artist/Title of Work Venue Choreographer/Creator Cydney Wilkes 16 Falls in Color & Searching for Girl DTW, Ethnic Folk Arts Center Johanna Boyce Johanna Boyce with the Calf Women & DTW Horse Men John Jesurun Chang in a Void Moon Pyramid Club Bottom Line Judith Ren-Lay The Grandfather Tapes Franklin Furnace Susan Marshall Concert DTW Susan Rethorst Son of Famous Men P. -

Concerts with the London Philharmonic Orchestra for Seasons 1946-47 to 2006-07 Last Updated April 2007

Artistic Director NEVILLE CREED President SIR ROGER NORRINGTON Patron HRH PRINCESS ALEXANDRA Concerts with the London Philharmonic Orchestra For Seasons 1946-47 To 2006-07 Last updated April 2007 From 1946-47 until April 1951, unless stated otherwise, all concerts were given in the Royal Albert Hall. From May 1951 onwards, unless stated otherwise, all concerts were given in The Royal Festival Hall. 1946-47 May 15 Victor De Sabata, The London Philharmonic Orchestra (First Appearance), Isobel Baillie, Eugenia Zareska, Parry Jones, Harold Williams, Beethoven: Symphony 8 ; Symphony 9 (Choral) May 29 Karl Rankl, Members Of The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Kirsten Flagstad, Joan Cross, Norman Walker Wagner: The Valkyrie Act 3 - Complete; Funeral March And Closing Scene - Gotterdammerung 1947-48 October 12 (Royal Opera House) Ernest Ansermet, The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Clara Haskil Haydn: Symphony 92 (Oxford); Mozart: Piano Concerto 9; Vaughan Williams: Fantasia On A Theme Of Thomas Tallis; Stravinsky: Symphony Of Psalms November 13 Bruno Walter, The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Isobel Baillie, Kathleen Ferrier, Heddle Nash, William Parsons Bruckner: Te Deum; Beethoven: Symphony 9 (Choral) December 11 Frederic Jackson, The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Ceinwen Rowlands, Mary Jarred, Henry Wendon, William Parsons, Handel: Messiah Jackson Conducted Messiah Annually From 1947 To 1964. His Other Performances Have Been Omitted. February 5 Sir Adrian Boult, The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Joan Hammond, Mary Chafer, Eugenia Zareska, -

FY17 Annual Report View Report

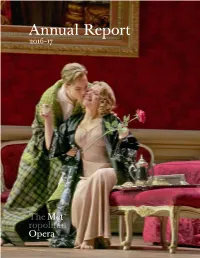

Annual Report 2016–17 1 2 4 Introduction 6 Metropolitan Opera Board of Directors 7 Season Repertory and Events 14 Artist Roster 16 The Financial Results 48 Our Patrons 3 Introduction In the 2016–17 season, the Metropolitan Opera continued to present outstanding grand opera, featuring the world’s finest artists, while maintaining balanced financial results—the third year running in which the company’s finances were balanced or very nearly so. The season opened with the premiere of a new production of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde and also included five other new stagings, as well as 20 revivals. The Live in HD series of cinema transmissions brought opera to audiences around the world for the 11th year, with ten broadcasts reaching approximately 2.3 million people. Combined earned revenue for the Met (Live in HD and box office) totaled $111 million. Total paid attendance for the season in the opera house was 75%. All six new productions in the 2016–17 season were the work of distinguished directors who had previous success at the Met. The compelling Opening Night new production of Tristan und Isolde was directed by Mariusz Treliński, who made his Met debut in 2015 with the double bill of Tchaikovsky’s Iolanta and Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle. French-Lebanese director Pierre Audi brought his distinctive vision to Rossini’s final operatic masterpiece Guillaume Tell, following his earlier staging of Verdi’s Attila in 2010. Robert Carsen, who first worked at the Met in 1997 on his popular production of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin, directed a riveting new Der Rosenkavalier, the company’s first new staging of Strauss’s grand comedy since 1969.