Northumbria Research Link

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electronic Business Application Analysis

Trinity College Dublin Colaiste na Trionoide, Baile Atha Cliath University of Dublin What is the optimal design of a Mountain Rescue Patient Assessment Smartphone Application? Rita Darcy A dissertation submitted to Trinity College Dublin, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Health Informatics 2016 Declaration I declare that the work described in this dissertation is, except where otherwise stated, entirely my own work, and has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university. I further declare that this research has been carried out in full compliance with the ethical research requirements of the School of Computer Science and Statistics, Trinity College Dublin. Signed: ___________________ Rita Darcy 24th June 2016 ii Permission to lend and/or copy I agree that the School of Computer Science and Statistics, Trinity College Dublin, may lend or copy this dissertation upon request. Signed: ___________________ Rita Darcy 24th June 2016 iii Abstract The purpose of this study is to explore what is the optimal design of a patient assessment Smartphone application that will be used by Mountain Rescue team members. It is proposed that a suitably designed application could assist Mountain Rescue team members in conducting and recording a patient assessment during a callout. A review was conducted of existing First Aid and Mountain Rescue apps. A Smartphone app was discovered that assists with patient assessments in remote emergency care situations, called the NOLS (National Outdoor Learning School) SOAP (Subjective, Objective, Assessment and Plan) Note Smartphone application. This application could potentially be used in Mountain Rescue. -

Guidelines Clinical Practice Guidelines

Clinical Practice - 2017 Edition Guidelines (UPDATED FEBRUARY 2018) ADVANCED PARAMEDIC AP Clinical Practice Guidelines - 2017 Edition (Updated February 2018) 1 Clinical Practice Guidelines - 2017 Edition (Updated February 2018) PRACTITIONER Advanced Paramedic These CPGs are dedicated to the memory of Dr Geoff King, the inaugural Director of the Pre-Hospital Emergency Care Council (PHECC), who sadly passed away in August 2014. Geoff was a true leader who had the ability to influence change through his own charismatic presence, vision and the respect he showed to all who met and dealt with him. He had an ability to empower others to perform and achieve to a “higher standard”. Geoff’s message was consistent “If you always put the patient first when making a decision, you will never make the wrong decision”. His immense legacy is without equal. Ní bheidh a leithéid arís ann. 1 Clinical Practice Guidelines - 2017 Edition (Updated February 2018) Advanced Paramedic PHECC Clinical Practice Guidelines First Edition, 2001 Second Edition, 2004 Third Edition, 2009 Third Edition, Version 2, 2011 Fourth Edition, April 2012 Fifth Edition, July 2014 Sixth Edition, March 2017 Published by: Pre-Hospital Emergency Care Council 2nd Floor, Beech House, Millennium Park, Osberstown, Naas, Co Kildare, W91 TK7N, Ireland. Phone: +353 (0)45 882042 Fax: + 353 (0)45 882089 Email: [email protected] Web: www.phecc.ie ISBN 978-0-9929363-6-5 © Pre-Hospital Emergency Care Council 2017 Permission is hereby granted to redistribute this document, in whole or part, for educational, non-commercial purposes providing that the content is not altered and that the Pre-Hospital Emergency Care Council (PHECC) is appropriately credited for the work. -

Clinical Practice Guidelines - 2017 Edition FIRST AID RESPONDER

Clinical Practice Guidelines - 2017 Edition FIRST AID RESPONDER FAR Clinical Practice Guidelines - 2017 Edition 1 Clinical Practice Guidelines - 2017 Edition RESPONDER First Aid Responder These CPGs are dedicated to the memory of Dr Geoff King, the inaugural Director of the Pre-Hospital Emergency Care Council (PHECC), who sadly passed away in August 2014. Geoff was a true leader who had the ability to influence change through his own charismatic presence, vision and the respect he showed to all who met and dealt with him. He had an ability to empower others to perform and achieve to a “higher standard”. Geoff’s message was consistent “If you always put the patient first when making a decision, you will never make the wrong decision”. His immense legacy is without equal. Ní bheidh a leithéid arís ann. 1 Clinical Practice Guidelines - 2017 Edition First Aid Responder PHECC Clinical Practice Guidelines First Edition, 2001 Second Edition, 2004 Third Edition, 2009 Third Edition, Version 2, 2011 Fourth Edition, April 2012 Fifth Edition, July 2014 Sixth Edition, March 2017 Published by: Pre-Hospital Emergency Care Council Abbey Moat House, Abbey Street, Naas, Co. Kildare, W91 NN9V, Ireland Phone: +353 (0)45 882042 Fax: + 353 (0)45 882089 Email: [email protected] Web: www.phecc.ie ISBN 978-0-9929363-6-5 © Pre-Hospital Emergency Care Council 2017 Permission is hereby granted to redistribute this document, in whole or part, for educational, non-commercial purposes providing that the content is not altered and that the Pre-Hospital Emergency Care Council (PHECC) is appropriately credited for the work. -

Level 4 – Emergency Medical Technician (EMT)

PHECC National Qualification in Emergency Medical Technology (NQEMT) Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) Assessment Sheets Level 4 – Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) This section of the NQEMT‐EMT examination consists of eight (8) OSCE stations in total. Primary stations Four (4) OSCEs will be drawn from the skills objectives relating to PHECC’s Education and Training Standards, 2011, Learning Outcome 1, Domain 1; and Learning Outcome 1, Domain 2. AND Secondary stations Four (4) secondary OSCEs will be drawn randomly from the skills & objectives relating to PHECC’s Education and Training Standards, 2011. General notes OSCE assessment sheets for inclusion in an NQEMT examination will be available on www.phecc.ie for a minimum of sixty (60) days prior to the examination. White text on a black background indicates either an instruction to the examiner/candidate or separates two distinct skills on the assessment sheet. Successful completion of each OSCE requires the candidate to score 80% of each station’s elements. Critical elements, which the candidate must successfully achieve in order to successfully complete the station, are marked with an asterisk (*) on the assessment sheet. There are no critical elements on secondary assessment sheets. Primary Assessment Sheets Patient Assessment Assessment Name: Vital Signs Unique Identifier: EMT_SSMA_P001 Level / Section: EMT / Patient Assessment Current Version: Version 2 (August 2011) Candidate Number: Assessment Date: Candidate is requested to demonstrate the following skills. Radial -

EMT Assessment Sheets for Web Version 5 Page: 1 of 39 Owner: LD Examination Quality Committee Approval Date: September 2015

Title: EMT Assessment Sheets for Web Version 5 Page: 1 of 39 Owner: LD Examination Quality Committee Approval Date: September 2015 PHECC National Qualification in Emergency Medical Technology (NQEMT) Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) Assessment Sheets Level 4 – Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) This section of the NQEMT‐EMT examination consists of eight (8) OSCE stations in total. Primary stations Four (4) OSCEs will be drawn from the skills objectives relating to PHECC’s Education and Training Standards, 2014, Learning Outcome 1, Domain 1; and Learning Outcome 1, Domain 2. AND Secondary stations Four (4) secondary OSCEs will be drawn randomly from the skills & objectives relating to PHECC’s Education and Training Standards, 2014. General notes OSCE assessment sheets for inclusion in an NQEMT examination will be available on www.phecc.ie for a minimum of sixty (60) days prior to the examination. White text on a black background indicates either an instruction to the examiner/candidate or separates two distinct skills on the assessment sheet. Successful completion of each OSCE requires the candidate to score 80% of each station’s elements. Critical elements, which the candidate must successfully achieve in order to successfully complete the station, are marked with an asterisk (*) on the assessment sheet. There are no critical elements on secondary assessment sheets. Primary Assessment Sheets September 2015 Patient Assessment Assessment Name: Vital Signs Unique Identifier: EMT_SSMA_P001 Level / Section: EMT / Patient Assessment -

Public Consultation on PHECC's Draft 2011 Education and Tr

Date: September 2010 To: Targeted audience Re: Public consultation on PHECC’s Draft 2011 Education and Training Standard From: Michael Garry, Chair of the Accreditation committee I would like to take this opportunity on behalf of the Pre‐Hospital Emergency Care Council to request your time to respond to this public consultation on the next edition of PHECC’s education and training standard 2011. I would also very much appreciate if you would circulate this information widely throughout your organisation. Background The current education and training standards (Edition 1) was approved by Council in April 2007. This standard has been the framework for upwards of 40 recognised institutions to deliver over 120 recognised pre‐hospital emergency care courses and to make responder level awards. In 2008, Council commissioned an external educational review of the existing suite of clinical courses and the work by Dr. Hemal Thakore is acknowledged. Subsequently, every recognised course was re‐ examined to ensure consistency with the current edition of CPGs, other PHECC standards and the evolving scope of practice of practitioners and responders. Emergency Care is the title of the proposal for a new level responder course that aims to bridge the divide between cardiac first response and emergency first response courses. Council rules have also been revisited and the purpose of this consultation is to identify if there is consensus that all the issues relating to the recognition of institutions and courses are comprehensively addressed. How is the 2011 standard constructed? The development of the standard is a major project necessitating in part a review of existing material, for other areas new material is proposed or remains a work in progress. -

Level 4 – Emergency Medical Technician (EMT)

Title: EMT Assessment Sheets with Scenarios Version 6 Page: 1 of 86 Owner: LD Examination Quality Committee Approval Date: March 2017 PHECC National Qualification in Emergency Medical Technology (NQEMT) Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) Assessment Sheets Level 4 – Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) This section of the NQEMT‐EMT examination consists of eight (8) OSCE stations in total. Primary stations Four (4) OSCEs will be drawn from the skills objectives relating to PHECC’s Education and Training Standards, 2017, Learning Outcome 1, Domain 1; and Learning Outcome 1, Domain 2. AND Secondary stations Four (4) secondary OSCEs will be drawn randomly from the skills & objectives relating to PHECC’s Education and Training Standards, 2017. General notes OSCE assessment sheets for inclusion in an NQEMT examination will be available on www.phecc.ie for a minimum of sixty (60) days prior to the examination. White text on a black background indicates either an instruction to the examiner/candidate or separates two distinct skills on the assessment sheet. Successful completion of each OSCE requires the candidate to score 80% of each station’s elements. Critical elements, which the candidate must successfully achieve in order to successfully complete the station, are marked with an asterisk (*) on the assessment sheet. There are no critical elements on secondary assessment sheets. Page 1 of 26 Primary Assessment Sheets 2017 Page 2 of 26 Assessment Name: Vital Signs Unique Identifier: EMT_SSMA_P001 Level / Section: EMT / Patient Assessment -

St Richard's Hospital Quality Report

Western Sussex Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust St Richard's Hospital Quality Report Spitalfield Lane Chichester West Sussex PO19 6SE Date of inspection visit: 9, 10, 11 & 21 December Tel: 01243 788122 2015 Website: www.westernsussexhospitals.nhs.uk Date of publication: 20/04/2016 This report describes our judgement of the quality of care at this hospital. It is based on a combination of what we found when we inspected, information from our ‘Intelligent Monitoring’ system, and information given to us from patients, the public and other organisations. Ratings Overall rating for this hospital Outstanding – Urgent and emergency services Outstanding – Medical care (including older people’s care) Outstanding – Surgery Good ––– Critical care Requires improvement ––– Maternity and gynaecology Outstanding – Services for children and young people Outstanding – End of life care Outstanding – Outpatients and diagnostic imaging Good ––– 1 St Richard's Hospital Quality Report 20/04/2016 Summary of findings Letter from the Chief Inspector of Hospitals Western Sussex Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust became a foundation trust on 1 July 2013, just over four years after the organisation was created by a merger of the Royal West Sussex and Worthing and Southlands Hospitals NHS Trusts. St Richard's Hospital in Chichester, West Sussex is one of three hospitals provided by the trust. The trust serves a population of around 450,000 across a catchment area covering most of West Sussex. The three hospitals are situated in the local authorities of Worthing, Chichester and Adur. These areas have a higher proportion of over 65's compared to the England average. The three local authorities have a lower proportion of ethnic minority populations compared to the England average. -

First Aid Mnemonics

First Aid Mnemonics General first aid mnemonics > DR ABC (primary survey) Danger Response Airway, Breathing Circulation/Compressions/Call an ambulance > HEAD (general methodology) History Examination Action Documentation > CHAT (general methodology) Chief complaint History Allergies Treatment Major incident > METHANE Major incident declared Exact location Type of incident Hazards (present and future) Access A first aid training resource provided by firstaidforfree.com Number, type, severity of casualties Emergency services now present and those required > CHALETS Casualties, number, type, severity Hazards (present and future) Access routes that are safe to use Location Emergency services present and required Type of incident Safety History taking > SAMPLE (questions to ask casualties) Signs & symptoms Allergies Medication Previous relevant medical history Last oral intake Event history > PQRST-U (assessing pain) Provoke - what provokes the pain? Quality - what is the pain like? Sharp? Dull? Ache? Radiates - does the pain go anywhere else? Severity - how bad is the pain on a scale of 0 - 10. Time - when did the pain start/finish. U - what do you think about the pain? Is this normal for you? Have you had this before? > SOCRATES (assessing pain) Site - where is the pain? Onset - when did the pain begin? A first aid training resource provided by firstaidforfree.com Character - Sharp? Dull? Ache? Radiation - does the pain go anywhere? Associated symptoms - any other symptoms? e.g: Nausea & Vomiting Timing - when did the pain begin? Exacerbating -

Worthing Hospital Newapproachcomprehensive Report

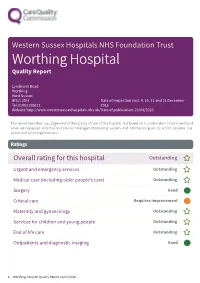

Western Sussex Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Worthing Hospital Quality Report Lyndhurst Road Worthing West Sussex BN11 2DH Date of inspection visit: 9, 10, 11 and 21 December Tel:01903 205111 2015 Website:http://www.westernsussexhospitals.nhs.uk/Date of publication: 20/04/2016 This report describes our judgement of the quality of care at this hospital. It is based on a combination of what we found when we inspected, information from our ‘Intelligent Monitoring’ system, and information given to us from patients, the public and other organisations. Ratings Overall rating for this hospital Outstanding – Urgent and emergency services Outstanding – Medical care (including older people’s care) Outstanding – Surgery Good ––– Critical care Requires improvement ––– Maternity and gynaecology Outstanding – Services for children and young people Outstanding – End of life care Outstanding – Outpatients and diagnostic imaging Good ––– 1 Worthing Hospital Quality Report 20/04/2016 Summary of findings Letter from the Chief Inspector of Hospitals We carried out an announced inspection visit from 9 to 11 December 2015. We held focus groups with a range of hospital staff including; nurses of all grades, junior doctors, consultants, midwives, student nurses, administrative and clerical staff, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, pharmacists, domestic staff, porters and volunteers. We also spoke with staff individually. We talked with patients and staff from all ward areas and outpatient services. We observed how people were being cared for, talked with carers and/or family members and reviewed patient records of personal care and treatment. We carried out an unannounced inspection on 21 December 2015 at Worthing Hospital. Overall we found that Western Sussex Hospitals Foundation NHS Trust was providing outstanding care and treatment from Worthing Hospital.