Linking Biodiversity Conservation and Poverty Alleviation: a State of Knowledge Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POVERTY and REFORMS in INDIA T. N. Srinivasan1

December 1999 POVERTY AND REFORMS IN INDIA T. N. Srinivasan1 Samuel C. Park, Jr. Professor of Economics Chairman, Department of Economics Yale University 1. Introduction The overarching objective of India's development strategy has always been the eradication of mass poverty. This objective has been articulated in several development plans, ranging from those published in the pre-independence era by individuals and organizations to the nine five year plans, and annual development plans since 1950 (Srinivasan 1999, lecture 3). However actual achievement has been very modest. In year 1997, five decades after independence, a little over a third of India's nearly billion population is estimated to be poor according to India's National Sample Survey (Table 1). It is also clear from the same table that until the late seventies, the national poverty ratio fluctuated with no significant time trend, between a low of 42.63 percent during April-September 1952 to a high of 62 percent July 1966-June 1967, the second of two successive years of severe drought. Then between July 1977-June 1978 and July 1990-June 1991, just prior to the introduction of systemic reforms of the economy following a severe economic crisis, the national poverty ratio declined significantly from 48.36 percent to 35.49 percent. The macroeconomic stabilization measures adopted at the same time as systemic reforms in July 1991 resulted in the stagnation of real GDP in 1991-92 relative to the previous 1I have drawn extensively on the research of Gaurav Datt and Martin Ravallion of the World Bank in writing this note. -

Strengthening of Panchayats in India: Comparing Devolution Across States

Strengthening of Panchayats in India: Comparing Devolution across States Empirical Assessment - 2012-13 April 2013 Sponsored by Ministry of Panchayati Raj Government of India The Indian Institute of Public Administration New Delhi Strengthening of Panchayats in India: Comparing Devolution across States Empirical Assessment - 2012-13 V N Alok The Indian Institute of Public Administration New Delhi Foreword It is the twentieth anniversary of the 73rd Amendment of the Constitution, whereby Panchayats were given constitu- tional status.While the mandatory provisions of the Constitution regarding elections and reservations are adhered to in all States, the devolution of powers and resources to Panchayats from the States has been highly uneven across States. To motivate States to devolve powers and responsibilities to Panchayats and put in place an accountability frame- work, the Ministry of Panchayati Raj, Government of India, ranks States and provides incentives under the Panchayat Empowerment and Accountability Scheme (PEAIS) in accordance with their performance as measured on a Devo- lution Index computed by an independent institution. The Indian Institute of Public Administration (IIPA) has been conducting the study and constructing the index while continuously refining the same for the last four years. In addition to indices on the cumulative performance of States with respect to the devolution of powers and resources to Panchayats, an index on their incremental performance,i.e. initiatives taken during the year, was introduced in the year 2010-11. Since then, States have been awarded for their recent exemplary initiatives in strengthening Panchayats. The Report on"Strengthening of Panchayats in India: Comparing Devolution across States - Empirical Assessment 2012-13" further refines the Devolution Index by adding two more pillars of performance i.e. -

Participating Manfacturers' Brands Approved for Sale

Participating Manufacturers' Brands Brand Family Brand Code Manufacturer 1839 000270 PREMIER MANUFACTURING, INC. 1839 (RYO) 000271 PREMIER MANUFACTURING, INC. 1ST CLASS 000171 PREMIER MANUFACTURING, INC. ACE 000080 KING MAKER MARKETING INC AMERICAN BISON 000292 WIND RIVER TOBACCO COMPANY LLC AMERICAN BISON (RYO) 000293 WIND RIVER TOBACCO COMPANY LLC BALI SHAG (RYO) 000013 TOP TOBACCO LP BARON AMERICAN BLEND 000064 FARMERS TOBACCO CO OF CYNTHIANA INC BASIC 000149 PHILIP MORRIS USA INC BENSON & HEDGES 000150 PHILIP MORRIS USA INC BLACK & GOLD 000227 SHERMANS 1400 BROADWAY NYC LTD BUGLER (RYO) 000595 SCANDINAVIAN TOBACCO GROUP LANE LIMITED CAMBRIDGE 000152 PHILIP MORRIS USA INC CAMEL 000185 R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY CAMEL WIDES 000186 R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY CANOE (RYO) 000294 WIND RIVER TOBACCO COMPANY LLC CAPRI 000187 R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY CARLTON 000188 R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY CHECKERS 000081 KING MAKER MARKETING INC CHESTERFIELD 000154 PHILIP MORRIS USA INC CIGARETTELLOS 000228 SHERMANS 1400 BROADWAY NYC LTD CLASSIC 000229 SHERMANS 1400 BROADWAY NYC LTD CROWNS 000593 COMMONWEALTH BRANDS INC CUSTOM BLENDS (RYO) 000295 WIND RIVER TOBACCO COMPANY LLC DAVE'S 000620 PHILIP MORRIS USA INC DAVIDOFF 000014 COMMONWEALTH BRANDS INC DORAL 000189 R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY DREAMS 000628 KRETEK INTERNATIONAL INC. July 26, 2021 Page 1 of 4 Brand Family Brand Code Manufacturer DRUM (RYO) 000260 TOP TOBACCO LP DUNHILL 000190 R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY DUNHILL INTERNATIONAL 000191 R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY EAGLE 20'S 000277 VECTOR TOBACCO INC D/B/A MEDALLION BRANDS ECLIPSE 000192 R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY EVE 000105 LIGGETT GROUP LLC FANTASIA 000230 SHERMANS 1400 BROADWAY NYC LTD FORTUNA 000015 COMMONWEALTH BRANDS INC GAMBLER (RYO) 000261 TOP TOBACCO LP GAULOISES 000016 COMMONWEALTH BRANDS INC GITANES 000017 COMMONWEALTH BRANDS INC GOLD CREST 000083 KING MAKER MARKETING INC GPC 000194 R.J. -

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 11/20/09

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 11/20/09 Beginning August 1, 2008, only the cigarette brands and styles listed below are allowed to be imported, stamped and/or sold in the State of Alaska. Per AS 18.74, these brands must be marked as fire safe on the packaging. The brand styles listed below have been certified as fire safe by the State Fire Marshall, bear the "FSC" marking. There is an exception to these requirements. The new fire safe law allows for the sale of cigarettes that are not fire safe and do not have the "FSC" marking as long as they were stamped and in the State of Alaska before August 1, 2008 and found on the "Directory of MSA Compliant Cigarette & RYO Brands." Filter/ Non- Brand Style Length Circ. Filter Pkg. Descr. Manufacturer 1839 Full Flavor 82.7 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 97 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 83 24.60 Non-Filter Soft Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 83 24.40 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 83 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol Light 83 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. -

Poverty and Fertility in India: Some Factors Contributing to a Positive Correlation

Global Majority E-Journal, Vol. 2, No. 2 (December 2011), pp. 87-98 Poverty and Fertility in India: Some Factors Contributing to a Positive Correlation Brittany Traeger Abstract India has diminishing population growth rates and fertility rates; however, they still remain high compared to the world average. The families living in poverty are those having the most children because they are consistently trapped in poverty from generation to generation with little opportunity. Poor families are typically larger because they use children as a source of generating income via child labor. Parents also have children for insurance purposes because they envision needing help when they get older. All children born into poverty, especially girls, have little opportunity to escape from it in adulthood because of the lack of education and power. Another cause for high fertility rates is the large unmet need for family planning among the poor. Investing in family planning amongst the poor would be efficient to reduce fertility rates and poverty. Furthermore, increases in school enrollments, (including for girls) result in more power for females and thus decreasing fertility rates. I. Introduction Currently, about one quarter of India’s population lives in poverty, i.e., on less than one dollar-a- day. 1 This is a sharp decrease from what the poverty rate was in previous decades but it remains high. India also remains to have relatively high fertility and population growth rates. Many consider high poverty and high fertility to be a vicious cycle poor people are caught in. The vicious cycle is that females of poor families get married at a young age and typically have many children. -

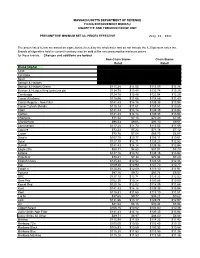

Cigarette Minimum Retail Price List

MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE FILING ENFORCEMENT BUREAU CIGARETTE AND TOBACCO EXCISE UNIT PRESUMPTIVE MINIMUM RETAIL PRICES EFFECTIVE July 26, 2021 The prices listed below are based on cigarettes delivered by the wholesaler and do not include the 6.25 percent sales tax. Brands of cigarettes held in current inventory may be sold at the new presumptive minimum prices for those brands. Changes and additions are bolded. Non-Chain Stores Chain Stores Retail Retail Brand (Alpha) Carton Pack Carton Pack 1839 $86.64 $8.66 $85.38 $8.54 1st Class $71.49 $7.15 $70.44 $7.04 Basic $122.21 $12.22 $120.41 $12.04 Benson & Hedges $136.55 $13.66 $134.54 $13.45 Benson & Hedges Green $115.28 $11.53 $113.59 $11.36 Benson & Hedges King (princess pk) $134.75 $13.48 $132.78 $13.28 Cambridge $124.78 $12.48 $122.94 $12.29 Camel All others $116.56 $11.66 $114.85 $11.49 Camel Regular - Non Filter $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Camel Turkish Blends $110.14 $11.01 $108.51 $10.85 Capri $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Carlton $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Checkers $71.54 $7.15 $70.49 $7.05 Chesterfield $96.53 $9.65 $95.10 $9.51 Commander $117.28 $11.73 $115.55 $11.56 Couture $72.23 $7.22 $71.16 $7.12 Crown $70.76 $7.08 $69.73 $6.97 Dave's $107.70 $10.77 $106.11 $10.61 Doral $127.10 $12.71 $125.23 $12.52 Dunhill $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Eagle 20's $88.31 $8.83 $87.01 $8.70 Eclipse $137.16 $13.72 $135.15 $13.52 Edgefield $73.41 $7.34 $72.34 $7.23 English Ovals $125.44 $12.54 $123.59 $12.36 Eve $109.30 $10.93 $107.70 $10.77 Export A $120.88 $12.09 $119.10 $11.91 -

A Comparison of Smoking Cessation Methods in Normal Smokers and Smokers with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Mary Beth Mueller University of Nebraska-Lincoln

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Open-Access* Master's Theses from the University Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln of Nebraska-Lincoln 5-1990 A Comparison of Smoking Cessation Methods in Normal Smokers and Smokers with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Mary Beth Mueller University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/opentheses Part of the Health and Physical Education Commons, Medical Education Commons, and the Public Health Education and Promotion Commons Mueller, Mary Beth, "A Comparison of Smoking Cessation Methods in Normal Smokers and Smokers with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease" (1990). Open-Access* Master's Theses from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. 12. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/opentheses/12 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open-Access* Master's Theses from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. A COMPARISON OF SMOKING CESSATION METHODS IN NORMAL SMOKERS AND SMOKERS WITH CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE by Mary Beth Mueller A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College in the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for the Degree of Master of Education Major: Health, Physical Education and Recreation Under the Supervision of Professor Gary L. Martin Lincoln, Nebraska May 1990 A COMPARISON OF THREE SMOKING CESSATION TREATMENT METHODS IN NORMAL SMOKERS AND CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE Mary Beth Mueller, M.Ed. University of Nebraska, 1990 Adviser: Gary L. -

MSA Compliant Tobacco Manufacturers Updated March 16, 2015

MSA Compliant Tobacco Manufacturers Updated March 16, 2015 The cigarette manufacturers and their associated brands listed below have been determined to be in compliance with Alaska Statute 45.53.020. In order The brands listed below include all variations, types, and sizes (e.g. menthol, king, and regular). Manufacturer type provides that the company is both a participating manufacturer (PM) and signatory to the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement and all For a comprehensive list of all brands and styles that can be sold in Alaska, please see the Directory of Cigarettes Approved for Sale and Importation. Manufacturer Manufacturer Type Brand Type Commonwealth Brands, Inc. PM Bali Shag RYO Commonwealth Brands, Inc. PM Crowns CIG Commonwealth Brands, Inc. PM Davidoff CIG Commonwealth Brands, Inc. PM Fortuna CIG Commonwealth Brands, Inc. PM Gauloises CIG Commonwealth Brands, Inc. PM Gitanes CIG Commonwealth Brands, Inc. PM Malibu CIG Commonwealth Brands, Inc. PM McClintock RYO Commonwealth Brands, Inc. PM Montclair CIG Commonwealth Brands, Inc. PM Premier RYO Commonwealth Brands, Inc. PM SF CIG Commonwealth Brands, Inc. PM Sonoma CIG Commonwealth Brands, Inc. PM USA Gold CIG Commonwealth Brands, Inc. PM West CIG Japan Tobacco International USA, Inc. PM Export 'A' CIG King Maker Marketing, Inc. PM Hi-Val CIG Kretek International, Inc. PM Taj Mahal CIG Liggett Group Inc. PM Eve CIG Liggett Group Inc. PM Grand Prix CIG Liggett Group Inc. PM Liggett Select CIG Liggett Group Inc. PM Montego CIG Liggett Group Inc. PM Pyramid CIG Lignum-2, Inc. PM Rave RYO Lorillard Tobacco Company PM Kent CIG Lorillard Tobacco Company PM Maverick CIG Lorillard Tobacco Company PM Newport CIG Lorillard Tobacco Company PM Old Gold CIG Lorillard Tobacco Company PM True CIG National Tobacco Company NPM Zig Zag RYO NASCO Products PM Magic CIG NASCO Products PM Red Sun CIG Native Trading Associates NPM Native CIG People's True Taste, Inc. -

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 4/29/10

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 4/29/10 Beginning August 1, 2008, only the cigarette brands and styles listed below are allowed to be imported, stamped and/or sold in the State of Alaska. Per AS 18.74, these brands must be marked as fire safe on the packaging. The brand styles listed below have been certified as fire safe by the State Fire Marshall, bear the "FSC" marking. There is an exception to these requirements. The new fire safe law allows for the sale of cigarettes that are not fire safe and do not have the "FSC" marking as long as they were stamped and in the State of Alaska before August 1, 2008 and found on the "Directory of MSA Compliant Cigarette & RYO Brands." Filter/ Non- Brand Style Length Circ. Filter Pkg. Descr. Manufacturer 1839 Full Flavor 82.7 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 97 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 83 24.60 Non-Filter Soft Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 83 24.40 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 83 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol Light 83 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. -

Historical Roots of Mass Poverty in South Asia

Historical Roots of Mass Poverty in South Asia A Hypothesis Tapan Raychaudhuri The contemporary phenomenon of underdevelopment is not a continuation of the traditional economic order of pre-modern times. The patterns of economic organisation and levels of economic performance in the traditional societies of Asia, before they were enmeshed into the international economy created by first the merchant and later the industrial capitalism of western Europe, were significantly different from their contemporary counterparts. In the case of India, the pre-colonial economy in its normal functioning did not generate large groups of half starving people. The author traces the roots of mass poverty in India, as we know it today, to the new institutional framework of agriculture introduced after 1813 which deprived small holders, both tenants and proprietors, of nearly all their surplus, if it did not actually reduce them to landlessness. Not only the new institutional arrangements, but even the positive developments in agriculture augmented the tradi- tional disparities of India's agrarian society. Thus development of a market for cash crops implied a change in the ratio of non-food crops to food crops until, with increases in population, the output of foodgrains per head of population declined quite sharply. And where irrigation provided the means of increasing productivity, those in control of large holdings tried and increased their holdings, often at the cost of the poorer agriculturists. The all-too-familiar phenomenon of today's mass poverty was thus already an established fact of life by the time population began to increase at a steady pace. -

Page 1 of 15

Updated September14, 2021– 9:00 p.m. Date of Next Known Updates/Changes: *Please print this page for your own records* If there are any questions regarding pricing of brands or brands not listed, contact Heather Lynch at (317) 691-4826 or [email protected]. EMAIL is preferred. For a list of licensed wholesalers to purchase cigarettes and other tobacco products from - click here. For information on which brands can be legally sold in Indiana and those that are, or are about to be delisted - click here. *** PLEASE sign up for GovDelivery with your EMAIL and subscribe to “Tobacco Industry” (as well as any other topic you are interested in) Future lists will be pushed to you every time it is updated. *** https://public.govdelivery.com/accounts/INATC/subscriber/new RECENTLY Changed / Updated: 09/14/2021- Changes to LD Club and Tobaccoville 09/07/2021- Update to some ITG list prices and buydowns; Correction to Pall Mall buydown 09/02/2021- Change to Nasco SF pricing 08/30/2021- Changes to all Marlboro and some RJ pricing 08/18/2021- Change to Marlboro Temp. Buydown pricing 08/17/2021- PM List Price Increase and Temp buydown on all Marlboro 01/26/2021- PLEASE SUBSCRIBE TO GOVDELIVERY EMAIL LIST TO RECEIVE UPDATED PRICING SHEET 6/26/2020- ***RETAILER UNDER 21 TOBACCO***(EFF. JULY 1) (on last page after delisting) Minimum Minimum Date of Wholesale Wholesale Cigarette Retail Retail Brand List Manufacturer Website Price NOT Price Brand Price Per Price Per Update Delivered Delivered Carton Pack Premier Mfg. / U.S. 1839 Flare-Cured Tobacco 7/15/2021 $42.76 $4.28 $44.00 $44.21 Growers Premier Mfg. -

Directory by Brand 02-27-06

3/2/2006 Brand Name Manufacturer C/RYO PM/NPM #117 National Tobacco Company RYO NPM 10/20's Dhanraj International C PM 10/20's Dhanraj International RYO PM 1st Choice R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company C PM 4Aces Top Tobacco, LP RYO PM A Hint of Mint Sherman's 1400 Broadway NYC, Ltd. C PM A Touch of Clove Sherman's 1400 Broadway NYC, Ltd. C PM Ace King Maker Marketing C PM All Star Liberty Brands C PM All-American Value Philip Morris C PM Alpine Philip Morris C PM Always Save Liberty Brands C PM American Bison Wind River Tobacco Company C PM American Bison Wind River Tobacco Company RYO PM American Blend Mac Baren Tobacco Company RYO PM Ashford Von Eicken Group C PM Ashford Von Eicken Group RYO PM Athey Daughters & Ryan, Inc. RYO PM Austin R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company C PM Bali Peter Stokkebye International, A/S RYO PM Barclay R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company C PM Bargain Buy R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company C PM Baron American Blend Farmer's Tobacco Co. of Cynthiana, Inc. C PM Basic Philip Morris C PM Beacon R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company C PM Belair R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company C PM Benson & Hedges Philip Morris C PM Best Buy Philip Morris C PM Best Choice Liberty Brands C PM Best Value R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company C PM Black & Gold Sherman's 1400 Broadway NYC, Ltd. C PM Bonus Value R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company C PM Boundary VIP Tobacco USA, Ltd. C PM Brand Marketing Liggett Group, Inc.