TIME, RHYTHM and MAGIC Developing a Communications Theory Approach to Documentary Film Editing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Expectations on Screen

UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE MADRID FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTORIA Y TEORÍA DEL ARTE TESIS DOCTORAL GREAT EXPECTATIONS ON SCREEN A Critical Study of Film Adaptation Violeta Martínez-Alcañiz Directoras de la Tesis Doctoral: Prof. Dra. Valeria Camporesi y Prof. Dra. Julia Salmerón Madrid, 2018 UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE MADRID FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTORIA Y TEORÍA DEL ARTE TESIS DOCTORAL GREAT EXPECTATIONS ON SCREEN A Critical Study of Film Adaptation Tesis presentada por Violeta Martínez-Alcañiz Licenciada en Periodismo y en Comunicación Audiovisual para la obtención del grado de Doctor Directoras de la Tesis Doctoral: Prof. Dra. Valeria Camporesi y Prof. Dra. Julia Salmerón Madrid, 2018 “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair” (Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities) “Now why should the cinema follow the forms of theater and painting rather than the methodology of language, which allows wholly new concepts of ideas to arise from the combination of two concrete denotations of two concrete objects?” (Sergei Eisenstein, “A dialectic approach to film form”) “An honest adaptation is a betrayal” (Carlo Rim) Table of contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 13 CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 15 CHAPTER 2. LITERATURE REVIEW 21 Early expressions: between hostility and passion 22 Towards a theory on film adaptation 24 Story and discourse: semiotics and structuralism 25 New perspectives 30 CHAPTER 3. -

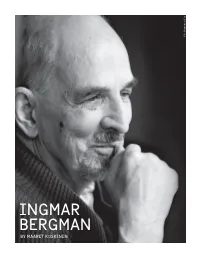

The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director

Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 19, 2009 11:55 Geoffrey Macnab writes on film for the Guardian, the Independent and Screen International. He is the author of The Making of Taxi Driver (2006), Key Moments in Cinema (2001), Searching for Stars: Stardom and Screenwriting in British Cinema (2000), and J. Arthur Rank and the British Film Industry (1993). Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director Geoffrey Macnab Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 Sheila Whitaker: Advisory Editor Published in 2009 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © 2009 Geoffrey Macnab The right of Geoffrey Macnab to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978 1 84885 046 0 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress -

In Search of a Concrete Music

In Search of a Concrete Music The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the Ahmanson Foundation Humanities Endowment Fund of the University of California Press Foundation. ni niVtirp im -tutt) n n )»h yViyn n »i »t m n j w TTtt-i 1111 I'n-m i i i lurfii'ii; i1 In Search of a Concrete Music CALIFORNIA STUDIES IN 20TH-CENTURY MUSIC Richard Taruskin, General Editor 1. Revealing Masks: Exotic Influences and Ritualized Performance in Modernist Music Theater, by W. Anthony Sheppard 2. Russian Opera and the Symbolist Movement, by Simon Morrison 3. German Modernism: Music and the Arts, by Walter Frisch 4. New Music, New Allies: American Experimental Music in West Germany from the Zero Hour to Reunification, by Amy Beal 5. Bartok, Hungary, and the Renewal of Tradition: Case Studies in the Intersection of Modernity and Nationality, by David E. Schneider 6. Classic Chic: Music, Fashion, and Modernism, by Mary E. Davis 7. Music Divided: Bartok's Legacy in Cold War Culture, by Danielle Fosler-Lussier 8. Jewish Identities: Nationalism, Racism, and Utopianism in Twentieth-Century Art Music, by Klara Moricz 9. Brecht at the Opera, by Joy H. Calico 10. Beautiful Monsters: Imagining the Classic in Musical Media, by Michael Long xi. Experimentalism Otherwise: The New York Avant-Garde and Its Limits, by Benjamin Piekut 12. Music and the Elusive Revolution: Cultural Politics and Political Culture in France, 1968-1981, by Eric Drott 13. Music and Politics in San Francisco: From the 1906 Quake to the Second World War, by Leta E. Miller 14. -

Musical Form in Non-Narrative Video

MUSICAL FORM IN NON-NARRATIVE VIDEO by Ellen Irene Sebring Bachelor of Music Indiana University SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN VISUAL STUDIES at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY September 1986 Copyright @ 1986 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Signature of Author E_ Ellen Irene Sebring Department of Architecture /'j.J f. June 17, 1986 Certified by Otto Piene, Professor of Visual Design Thesis Supervisor Accepted by -' Nicholas Negroponte Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students Rotch R ~ MusIcAL FORM IN NON-NARRATIVE VIDEO by Ellen Irene Sebring Submitted to the Department of Architecture on June 17, 1986 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Visual Studies. Abstract "Musical Form in Non-Narrative Video" explores musical structure as a model for visual form over time, specifically in the creation of artistic video. Video is a medium in which sound and image coexist at the source as electronic signals, offering new possibilities of abstract synesthesia. Forms in which neither sight nor sound dominants facilitate a sensory experience of the content. A musical model for abstract form supports an effort to free video from the forward-impelled, linear narrative; to create a form which can be experienced many times on multiple levels. Musical parameters such as meter, dynamics and motivic development are correlated to visual parameters. Their application in my own videotapes is analyzed. Experimental form-generated pieces are outlined. "Aviary" and "Counterpoint" are video scores which present two different approaches to music- image composition. -

Hybrid Sound Objects 31 4.1.Definitions 4.2.Sonic Event and Its Temporal Construction 4

1 Diegetic sonic behaviors applied to visual environments, a definition of the hybrid sound object and its implementations Emmanuel Flores Elías 2008 Institute of Sonology Royal Conservatory The Netherlands 2 Would like to thank all the people that helped this project to happen: To my dear Jiji for all her support, love and the Korean food. To my parents and my brother. Netherlands: Paul, Kees, Joost and all the teachers at Sonology. The friends: Danny, Luc and Tomer.. Mexico: María Antonieta, Víctor and all the people at the CIEM. Barcelona: Perfecto, Andrés and the Phonos Fundation. 3 .>Contents .>Introduction 4 .>Chapter 1: history of montage on the narrative audiovisual environments 7 1.1.Concept of montage 1.2.Russian montage theory: from Eisenstein to Vertov 1.3.French New Wave: from Godard to Rohmer 1.4.the film resonance in the work of Andrei Tarkovsky 1.5.editing and rhythm inside the dogme95: Lars von Triers 1.6.the noise perspective: Walter Murch and the sonic director 1.7.the video culture 1.8.the phenomenology of montage: Gustav Deutsch .>[First intermission]mise-en-scene and the visual cell 17 a.1.definitions a.2.speed and motion inside the shot a.3.time and mise-en-scene .>Chapter 2: elements of sound on audiovisual environments 19 2.1.sound inside the film 2.2.sound layers on cinema 2.3.use of sound layering on cinema 2.4.dimension of sound inside the audiovisual environment 2.4.1.first dimension: rhythm 2.4.2.second dimension: fidelity 2.4.3.third dimension: space 2.4.4.fourth dimension: time .>Chapter 3: diegetic field -

Tricks of the Light

Tricks of the Light: A Study of the Cinematographic Style of the Émigré Cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan Submitted by Tomas Rhys Williams to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film In October 2011 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. 1 Abstract The aim of this thesis is to explore the overlooked technical role of cinematography, by discussing its artistic effects. I intend to examine the career of a single cinematographer, in order to demonstrate whether a dinstinctive cinematographic style may be defined. The task of this thesis is therefore to define that cinematographer’s style and trace its development across the course of a career. The subject that I shall employ in order to achieve this is the émigré cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan, who is perhaps most famous for his invention ‘The Schüfftan Process’ in the 1920s, but who subsequently had a 40 year career acting as a cinematographer. During this time Schüfftan worked throughout Europe and America, shooting films that included Menschen am Sonntag (Robert Siodmak et al, 1929), Le Quai des brumes (Marcel Carné, 1938), Hitler’s Madman (Douglas Sirk, 1942), Les Yeux sans visage (Georges Franju, 1959) and The Hustler (Robert Rossen, 1961). -

100 Anni Di Ingmar Bergman

100 ANNI DI INGMAR BERGMAN settembre - dicembre 2018 UFFICIO CINEMA Collana a cura dell’Ufficio Cinema del Comune di Reggio Emilia piazza Casotti 1/c - 42121 Reggio Emilia telefono 0522/456632 - 456763 fax 0522/585241 cura rassegna e organizzazione 100 ANNI DI INGMAR BERGMAN Sandra Campanini cura catalogo Angela Cervi impaginazione Angela Cervi amministrazione Cinzia Biagi servizi tecnici Ero Incerti servizi diversi Giorgio Guerri Cinema Rosebud settembre - dicembre 2018 PROGRAMMA SOMMARIO lunedì 17 settembre 7 CIÒ CHE RISPONDE INGMAR BERGMAN, QUANDO RISPONDE • IL POSTO DELLE FRAGOLE (1957) 91’ 9 INTRODUZIONE di Jacques Mandelbaum lunedì 24 settembre 15 LO SCHIAFFO DI “LUCI D’INVERNO” • MONICA E IL DESIDERIO (1952) 92’ di Aldo Garzia mercoledì 7 novembre 21 I COLLEGHI REGISTI, LA CURIOSITÀ PER I GIOVANI di Aldo Garzia • IL SETTIMO SIGILLO (1957) 96’ LE SCHEDE lunedì 26 novembre 31 IL POSTO DELLE FRAGOLE • SUSSURRI E GRIDA (1972) 91’ 41 MONICA E IL DESIDERIO lunedì 10 dicembre 51 IL SETTIMO SIGILLO • SCENE DA UN MATRIMONIO (1975) 168’ 61 SUSSURRI E GRIDA 71 SCENE DA UN MATRIMONIO mercoledì 19 dicembre 79 FANNY E ALEXANDER • FANNY E ALEXANDER (1982) 188’ 93 BIOGRAFIA 101 FILMOGRAFIA 4 5 “”CIÒ CHE RISPONDE INGMAR BERGMAN, QUANDO RISPONDE” (Il regista)... È un illusionista. Se guardiamo l’elemento fondamentale dell’arte cinematografica constatiamo che questa si compone di piccole immagini rettangolari ognuna delle quali è separata dalle altre da una grossa riga nera. Guardando più da vicino si scopre che questi minuscoli rettangoli, i quali a prima vista sembrano contenere lo stesso motivo, differiscono l’uno dall’altro per una modificazione quasi impercettibile di tale motivo. -

On the Meaning of a Cut : Towards a Theory of Editing

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output On the meaning of a cut : towards a theory of editing https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40391/ Version: Full Version Citation: Dziadosz, Bartłomiej (2019) On the meaning of a cut : towards a theory of editing. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email ON THE MEANING OF A CUT: TOWARDS A THEORY OF EDITING Bartłomiej Dziadosz A dissertation submitted to the Department of English and Humanities in candidacy for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Birkbeck, University of London October 2018 Abstract I confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own and the work of other persons is appropriately acknowledged. This thesis looks at a variety of discourses about film editing in order to explore the possibility, on the one hand, of drawing connections between them, and on the other, of addressing some of their problematic aspects. Some forms of fragmentation existed from the very beginnings of the history of the moving image, and the thesis argues that forms of editorial control were executed by early exhibitors, film pioneers, writers, and directors, as well as by a fully- fledged film editor. This historical reconstruction of how the profession of editor evolved sheds light on the specific aspects of their work. Following on from that, it is proposed that models of editing fall under two broad paradigms: of montage and continuity. -

Ingmar Bergman by Maaret-Koskinen English.Pdf

Foto: Bengt Wanselius Foto: INGMAR BERGMAN BY MAARET KOSKINEN Ingmar Bergman by Maaret Koskinen It is now, in the year of 2018, almost twenty years ago that Ingmar Bergman asked me to “take a look at his hellofamess” in his private library at his residence on Fårö, the small island in the Baltic Sea where he shot many of his films from the 1960s on, and where he lived until his death in 2007, at the age of 89. S IT turned out, this question, thrown foremost filmmaker of all time, but is generally re Aout seemingly spontaneously, was highly garded as one of the foremost figures in the entire premeditated on Bergman’s part. I soon came to history of the cinematic arts. In fact, Bergman is understand that his aim was to secure his legacy for among a relatively small, exclusive group of film the future, saving it from being sold off to the highest makers – a Fellini, an Antonioni, a Tarkovsky – whose paying individual or institution abroad. Thankfully, family names rarely need to be accompanied by a Bergman’s question eventually resulted in Bergman given name: “Bergman” is a concept, a kind of “brand donating his archive in its entirety, which in 2007 name” in itself. was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List, and the subsequent formation of the Ingmar Bergman Bergman’s career as a cinematic artist is unique in Foundation (www.ingmarbergman.se). its sheer volume. From his directing debut in Crisis (1946) to Fanny and Alexander (1982), he found time The year of 2018 is also the commemoration of to direct more than 40 films, including some – for Bergman’s birth year of 1918. -

·ļ¯Æ ¼Æ›¼ Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

è‹±æ ¼çŽ›Â·ä¼¯æ ¼æ›¼ 电影 串行 (大全) Ingmar Bergman's https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/ingmar-bergman%27s-cinema-59725709/actors Cinema Herr Sleeman kommer https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/herr-sleeman-kommer-28153912/actors FÃ¥rö trilogy https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/f%C3%A5r%C3%B6-trilogy-12043076/actors Crisis https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/crisis-1066211/actors The Blessed Ones https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-blessed-ones-1079728/actors Port of Call https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/port-of-call-1108471/actors Thirst https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/thirst-1188701/actors FÃ¥rö Document 1979 https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/f%C3%A5r%C3%B6-document-1979-18239069/actors Stimulantia https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/stimulantia-222633/actors The Venetian https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-venetian-2276647/actors The Image Makers https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-image-makers-2755257/actors Don Juan https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/don-juan-3035815/actors FÃ¥rö Document https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/f%C3%A5r%C3%B6-document-64768851/actors metaphysical trilogy https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/metaphysical-trilogy-98970250/actors 女人的秘密 https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%E5%A5%B3%E4%BA%BA%E7%9A%84%E7%A7%98%E5%AF%86-1078811/actors é¢ å” https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%E9%9D%A2%E5%AD%94-1078890/actors 愛的一課 https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%E6%84%9B%E7%9A%84%E4%B8%80%E8%AA%B2-1091180/actors -

The Rhythm of the Void

Jay Plaat S4173538 Master Thesis MA Creative Industries Radboud University Nijmegen, 2015-2016 Supervisor: dr. Natascha Veldhorst Second reader: dr. László Munteán The Rhythm of the Void On the rhythm of any-space-whatever in Bresson, Tarkovsky and Winterbottom Index Abstract 1 Introduction 2 Chapter 1 The Autonomous Cinematic Space Discourse (Or How Space Differs in Emptiness) 16 Chapter 2 Cinematic Rhythm 26 Chapter 3 The Any-Space-Whatever without Borders (Or Why Bresson Secretly Made Lancelot du Lac for People Who Can’t See) 37 Chapter 4 The Neutral, Onirosigns and Any-Body-Whatevers in Nostalghia 49 Chapter 5 The Any-Space-Whatever-Anomaly of The Face of an Angel (Or Why the Only True Any-Space-Whatever Is a Solitary One) 59 Conclusion 68 Appendix 72 Bibliography, internet sources and filmography 93 Abstract This thesis explores the specific rhythmic dimensions of Gilles Deleuze’s concept of any- space-whatever, how those rhythmic dimensions function and what consequences they have for the concept of any-space-whatever. Chapter 1 comprises a critical assessment of the autonomous cinematic space discourse and describes how the conceptions of the main contributors to this discourse (Balázs, Burch, Chatman, Perez, Vermeulen and Rustad) differ from each other and Deleuze’s concept. Chapter 2 comprises a delineation of cinematic rhythm and its most important characteristics. Chapters 3, 4 and 5 comprise case study analyses of Robert Bresson’s Lancelot du Lac, Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia and Michael Winterbottom’s The Face of an Angel, in which I coin four new additions to the concept of any-space-whatever. -

Visnja Diss FINAL

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles ! ! ! ! Clint Mansell: Music in the Films Requiem for a Dream and The Fountain by Darren Aronofsky ! ! ! ! A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Music ! by ! Visnja Krzic ! ! 2015 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! © Copyright by Visnja Krzic 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION ! Clint Mansell: Music in the Films Requiem for a Dream and The Fountain by Darren Aronofsky ! by ! Visnja Krzic Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Ian Krouse, Chair ! This monograph examines how minimalist techniques and the influence of rock music shape the film scores of the British film composer Clint Mansell (b. 1963) and how these scores differ from the usual Hollywood model. The primary focus of this study is Mansell’s work for two films by the American director Darren Aronofsky (b. 1969), which earned both Mansell and Aronofsky the greatest recognition: Requiem for a Dream (2000) and The Fountain (2006). This analysis devotes particular attention to the relationship between music and filmic structure in the earlier of the two films. It also outlines a brief evolution of musical minimalism and explains how a composer like Clint Mansell, who has a seemingly unusual background for a minimalist, manages to meld some of minimalism’s characteristic techniques into his own work, blending them with aspects of rock music, a genre closer to his musical origins. This study also characterizes the film scoring practices that dominated Hollywood scores throughout the ii twentieth century while emphasizing the changes that occurred during this period of history to enable someone with Mansell’s background to become a Hollywood film composer.