The Islamic Movement in Israel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Islamic Movement in Israel: Ideology Vs

Center for Open Access in Science ▪ https://www.centerprode.com/ojsh.html Open Journal for Studies in History, 2021, 4(1), 11-24. ISSN (Online) 2620-066X ▪ https://doi.org/10.32591/coas.ojsh.0401.02011s _________________________________________________________________________ The Islamic Movement in Israel: Ideology vs. Pragmatism David Schwartz Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, ISRAEL Department of Political Science Daniel Galily South-West University “Neofit Rilski”, Blagoevgrad, BULGARIA Faculty of Philosophy, Department of Philosophical and Political Sciences Received: 24 February 2021 ▪ Accepted: 28 April 2021 ▪ Published Online: 2 May 2021 Abstract This study aims to present the Islamic Movement in Israel, its ideology and pragmatism. With progress and modernization, the Islamic movements in the Middle East realized that they could not deny progress, so they decided to join the mainstream and take advantage of technological progress in their favor. The movement maintains at least one website in which it publishes its way, and guides the audience. Although these movements seem to maintain a rigid ideology, they adapt themselves to reality with the help of many tools, because they have realized that reality is stronger than they are. The main points in the article are: The Status of Religion in Israel; The Legal Status of Muslim Sharia in Israel; Personal status according to Israeli law; The establishment of the Islamic Movement in Israel – Historical Background; The crystallization of movement; Theoretical Background – The Theory of Pragmatism; Ideology and goals of the Islamic Movement in Israel; The background to the split in the movement – the opposition to pragmatism; How the ideology of the movement is expressed in its activity? The movement’s attitudes toward the Israeli elections, the Oslo Accords and the armed struggle against Israel; How does pragmatism manifest itself in the movement’s activities? Keywords: Islamic Movement, Israel, ideology, pragmatism. -

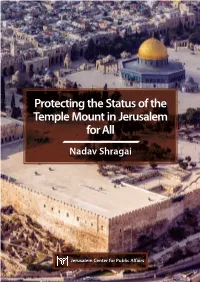

Protecting the Status of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem for All

The old status quo on the Temple Mount no longer exists and has lost its relevance. It has changed substantially according to a host of key parameters in a manner that has greatly enhanced the status of Muslims on the Mount and greatly undermined the status of Israeli Jews at the site. The situation on the Temple Mount continues to change periodically. The most blatant examples are the strengthening of Jordan’s position, the takeover of the Mount by the Northern Branch of the Islamic Movement in Israel and then its removal, and the severe curtailment of visits by Jews on the Mount. Protecting the Status of the At the same time, one of the core elements of the old status quo – the prohibition against Temple Mount in Jerusalem Jews praying on the Temple Mount – is strictly maintained. It appears that this is the most for All stable element in the original status quo. Unfortunately, the principle of freedom of Nadav Shragai religion for all faiths to visit and pray on the Temple Mount does not exist there today. Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs Protecting the Status of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem for All Nadav Shragai Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs 2016 Read this book online: http://jcpa.org/status-quo-temple-mount/ Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs Beit Milken, 13 Tel Hai St., Jerusalem, 92107, Israel Email: [email protected] Tel: 972-2-561-9281 Fax: 972-2-561-9112 © 2016 by Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs Cover image by Andrew Shiva ISBN: 978-965-218-131-2 Contents Introduction: The Temple Mount as a Catalyst for Palestinian Violence 5 Major Findings 11 The Role of the Temple Mount in the Summer 2014 Terror Wave 13 Changes on the Temple Mount following the October 2015 Terror Wave 19 The Status Quo in 1967: The Arrangement and Its Components 21 Prominent Changes in the Status Quo 27 1. -

Shaikh Raed Salah Accuses Non-Israelis of Trying to Ban Him from Al-Aqsa Mosque ۱۰:۱۲ - ۱۳۹۴/۰۱/۰۸

Shaikh Raed Salah accuses non-Israelis of trying to ban him from Al-Aqsa Mosque ۱۰:۱۲ - ۱۳۹۴/۰۱/۰۸ The leader of the Northern Branch of the Islamic Movement in Israel said on Thursday that a court's decision to imprison him is intended to keep him away from Al-Aqsa Mosque, in which Israelis want to allocate time for Jewish prayers. Shaikh Raed Salah insisted that it is also a way of increasing illegal settlements in Jerusalem; he accused non-Israeli parties, which he did not identify, of being behind this move to keep him away from the Noble Sanctuary. Speaking to Anadolu , Shaikh Raed said that the foreigners have "formed an alliance" with Israel to block Palestinian defence of Al-Aqsa from Israeli incursions. When asked if the non-Israelis were Arabs, he declined to elaborate further, saying only that the parties want to deter Palestinian efforts to defend the holy mosque against Israeli aggression. Pointing out that Israel's right-wing government has chosen a critical time to imprison him for 11 months, just as Jewish institutions are attacking Jerusalem, particularly Al-Aqsa Mosque, he noted that Palestinian areas inside Israel are also being threatened. "The most serious threat against Al-Aqsa Mosque are calls to destroy it and build a Temple structure in its place," Shaikh Salah explained. An Israeli court in Jerusalem sentenced him to 11 months in prison for "inciting violence" during a mosque sermon he gave in 2007. "Our warnings are not random," said the Palestinian leader, "and we stress that the future Israeli government's plan for Jerusalem are to divide the city and undermine the Palestinian existence there." He pointed out that Israel attacks him because he defends Al-Aqsa Mosque and Islamic heritage. -

Israel (Includes West Bank and Gaza) 2020 International Religious Freedom Report

ISRAEL (INCLUDES WEST BANK AND GAZA) 2020 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The country’s laws and Supreme Court rulings protect the freedoms of conscience, faith, religion, and worship, regardless of an individual’s religious affiliation. The 1992 Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty describes the country as a “Jewish and democratic state.” The 2018 Basic Law: Israel – The Nation State of the Jewish People law determines, according to the government, that “the Land of Israel is the historical homeland of the Jewish people; the State of Israel is the nation state of the Jewish People, in which it realizes its natural, cultural, religious and historical right to self-determination; and exercising the right to national self- determination in the State of Israel is unique to the Jewish People.” In June, authorities charged Zion Cohen for carrying out attacks on May 17 on religious institutions in Petah Tikva, Ashdod, Tel Aviv, and Kfar Saba. According to his indictment, Cohen sought to stop religious institutions from providing services to secular individuals, thereby furthering his goal of separating religion and the state. He was awaiting trial at year’s end. In July, the Haifa District Court upheld the 2019 conviction and sentencing for incitement of Raed Salah, head of the prohibited Islamic Movement, for speaking publicly in favor an attack by the group in 2017 that killed two police officers at the Haram al-Sharif/Temple Mount. In his defense, Salah stated that his views were religious opinions rooted in the Quran and that they did not include a direct call to violence. -

Arab Political Parties in the Occupied Lands of 1948 Mohammed Abu

Arab Political Parties in the Occupied Lands of 1948 Mohammed Abu Oun Introduction The 1948 Nakba was a major turning point in the lives of the Palestinian people. The Zionist gangs had occupied 78% of Palestine's lands and established the so-called 'Israel' state. The Israeli occupation displaced a huge part of the Palestinian people, but an equally great part survived and clung to their own cities and villages, or moved to nearby cities inside the occupied land to establish new communities away from the ones targeted by the occupation. The Palestinians suffered from disconnectedness as a result of the occupation's measures against them. It practiced all forms of oppression against the Palestinian people for the purpose of erasing their identity and eliminating their existence. The Palestinians in the occupied lands realized the occupation's attempts to dissect the Arabs' presence and oppression of their identity through its racist measures. Therefore, the people started working on establishing and organizing a Palestinian Arab community to save their identity and culture, and exercise pressure on the occupation for the protection of the Palestinians' rights. This study examines the main endeavors for and reasons behind forming Arab parties in the occupied lands of 1948, these parties' accomplishments and the ways the occupation dealt with them considering them a strategic threat against the occupation and its project. The research ends with a glimpse of the possible future of the Arab parties in the Israeli political system. Topic One: Palestinians' Conditions inside the Occupied Lands after 1948 Since 1948, the Palestinian people has been suffering from the occupation's atrocities, massacres and targeting of civilians; children, women and elderly. -

The Israeli Parliamentary Elections: a Splintering of the Arab Consensus?

INFO PACK The Israeli Parliamentary Elections: A Splintering of the Arab Consensus? Fatih Şemsettin Işık INFO PACK The Israeli Parliamentary Elections: A Splintering of the Arab Consensus? Fatih Şemsettin Işık The Israeli Parliamentary Elections: A Splintering of the Arab Consensus? © TRT WORLD RESEARCH CENTRE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED PUBLISHER TRT WORLD RESEARCH CENTRE March 2021 WRITTEN BY Fatih Şemsettin Işık PHOTO CREDIT ANADOLU AGENCY TRT WORLD İSTANBUL AHMET ADNAN SAYGUN STREET NO:83 34347 ULUS, BEŞİKTAŞ İSTANBUL / TURKEY TRT WORLD LONDON 200 GRAYS INN ROAD, WC1X 8XZ LONDON / UNITED KINGDOM TRT WORLD WASHINGTON D.C. 1819 L STREET NW SUITE, 700 20036 WASHINGTON DC / UNITED STATES www.trtworld.com researchcentre.trtworld.com The opinions expressed in this Info Pack represent the views of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the TRT World Research Centre. 4 The Israeli Parliamentary Elections: A Splintering of the Arab Consensus? Introduction n March 3, 2020, the leader of the alliance, it is clear that the representation of Arab Joint List, an alliance of four Arab citizens of Israel has been undermined by the latest parties in Israel, proudly declared departure. Moreover, Ra’am’s exit also revealed the that they had won a huge achieve- fragility and vulnerability of this alliance, a reality that O ment in the parliamentary elections reflects internal disputes between the parties. by winning 15 seats in the Knesset, a record for Arab parties in Israel. Ayman Odeh, the leader of Hadash This info pack presents the latest situation concern- (The Democratic Front for Peace and Equality) party, ing Arab political parties in Israel ahead of the March urged “actual equality between Arabs and Jews and 23 elections. -

Israeli Black Flags: Salafist Jihadi Representations in Israel And

Israeli Black Flags: Salast Jihadi Representations in Israel and the Rise of the Islamic State Organization Ariel Koch Over the last two years, the Islamic State organization has become one of the most dangerous elements in the Middle East. Its very existence, essence, and actions a!ect many nations throughout the world; its e!ect is most striking in the Middle East. This terrorist organization, "ying the black "ag as its o#cial banner, represents an extreme branch of orthodox Sunni Islam, challenging all existing orders of governance and seeking to replace them with an Islamic regime that imitates the conduct and way of life typical of the seventh century. This branch of Islam is called Sala$st jihadism, and is currently considered the most radical manifestation of Islamic fundamentalism. It is also thought to be the fastest-growing group within Islam, gathering supporters from all over the world. This essay seeks to shed light on Sala$st jihadism in general and on its Israeli adherents in particular, and to examine the reverberations felt in Israel as a result of the rise of this new power in Iraq and Syria. Keywords: Sala$, Sala$st jihadism, Islamic State, Israeli, Sheikh Nazem Abu Salim, Christians, Jews, global jihad, al-Qaeda, terrorism, Sharia Introduction A survey conducted by the General Security Service (GSS) on the spread of al-Qaeda’s ideology in Israel, indicated that in recent years the number of organizations identified with al-Qaeda and global jihad in the West Bank as well as within Israel had grown. 1 According to another document published by the GSS in 2012, the “growing identification with Salafist Ariel Koch is a researcher of jihadi propaganda in cyberspace and a doctoral student in the Department of Middle Eastern Studies at Bar Ilan University, under the supervision of Professor Michael M. -

The Withering of Arab Jerusalem

EXTREME MAKEOVER? (II): THE WITHERING OF ARAB JERUSALEM Middle East Report N°135 – 20 December 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. THE WITHERING AWAY OF ARAB JERUSALEM ................................................. 2 A. THE WEAKENING OF TRADITIONAL PALESTINIAN ACTORS .......................................................... 2 A. SOCIAL BREAKDOWN ................................................................................................................... 9 III. DIMINISHED HORIZONS ........................................................................................... 11 A. STAND YOUR GROUND .............................................................................................................. 11 1. Popular committees .................................................................................................................... 12 2. Haram al-Sharif (“Noble Sanctuary”) ........................................................................................ 14 B. EAST JERUSALEM’S NEW ISRAELI HINTERLAND? ....................................................................... 16 1. Solidarity movement .................................................................................................................. 16 2. Northern branch of the Islamic Movement ............................................................................... -

The-Sheikh-Raed-Salah-Affair.Pdf

Zulaikha Abdullah 1 2 Contents PAGE 1 Introduction 1 2 Who is Sheikh Raed and why the British fuss? 2 a. Career 2 i. The establishment and rise of the Islamic Movement 2 in Israel Ii. Politics and activism 5 Iii. Jerusalem 7 b. Harassment by Israeli authorities 8 3 Sheikh Raed’s visit 9 4 The media defamation campaign 10 5 The arrest & detention 12 6 The case against Sheikh Raed 15 a. The allegations 16 b. Legal hearings 22 i. The tribunal hearing 23 Ii. The bail appeal hearing 24 Iii. Permission to apply for judicial review hearing 25 Iv. The First-Tier Immigration Tribunal 26 7 The political fallout 29 i. Statements of support for Sheikh Raed from the 31 international community 8 Conclusion 36 9 Appendix 40 a. A response to accusations made against Sheikh Raed Salah, 40 Head of the Islamic Movement b. Transcript: Home Affairs Select Committee 5th July 43 © Middle East Monitor 2011 Title: The Sheikh Raed Salah Affair Published by Middle East Monitor 419-421 Crown House, North Circular Road, London, NW10 7PN T: 020 8838 0231 F: 020 8838 0705 E: [email protected] W: www.middleeastmonitor.org.uk Facebook: Middle East Monitor Twitter: @MiddleEastMnt ISBN: 978-1-907433-10-8 FRONT COVER AND TYPESET By M.A Khalid Saifullah A.M | www.salaamhosting.co.uk 3 The Sheikh Raed Affair Zulaikha Abdullah On 25 June 2011, the celebrated Palestinian social, political and civil rights leader, Sheikh Raed Salah, arrived at London‟s Heathrow airport at the invitation of the independent media research and information organisation, the Middle East Monitor (MEMO). -

Commentary… Million Annual Aid Package

בס״ד genuinely opposed עש״ק פרשת ואתחנן 12 Av 5777 ISRAEL NEWS stabbing Israeli August 4, 2017 civilians to death, he Issue number 1153 A collection of the week’s news from Israel would have done so immediately. From the Bet El Twinning / Israel Action Committee of Once 36 hours have passed, any Jerusalem 6:53 Beth Avraham Yoseph of Toronto Congregation statement he makes would be Toronto 8:20 completely meaningless – a transparent attempt to keep the U.S. Congress from cutting off his $500- Commentary… million annual aid package. No doubt Abbas will eventually issue some kind of mealy-mouthed statement opposing “violence on all sides.” Seven Lessons from the Halamish Massacre By Stephen M. Flatow Hopefully nobody will be fooled by such insincere blather. The Friday night slaughter of three Jews in the Israeli town of Halamish The other aspect of the PA’s response to the slaughter has to do with encapsulates pretty much everything one needs to know about the conflict how Omar al-Abed will be treated in the months and years ahead. The PA between the Palestinian Arabs and Israel. position is that all Palestinian terrorists imprisoned by Israel are “political It takes a special kind of savagery to murder people the way Omar al- prisoners” and should be released immediately. That now includes al- Abed did, repeatedly stabbing defenseless civilians at their dinner table. Abed. And as long as al-Abed is in prison, he will be receiving a And there have been so many similar attacks. The Halamish massacre was handsome salary from the PA, calibrated according to the number of Jews not an aberration; it is exactly what countless Palestinians do, or aspire to he killed. -

A1. International Crisis Group, Report on Israel's Arab Minority And

DOCUMENTS AND SOURCE MATERIAL INTERNATIONAL Palestinians in the occupied territories but also its own Palestinian minority. A1. INTERNATIONAL CRISIS GROUP, As Palestinians in Israel organized ral- REPORT ON ISRAEL’S ARAB MINORITY lies in solidarity with Gazans and West AND THE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT, Bankers, Israeli Jews grew ever more NAZARETH/JERUSALEM/RAMALLAH/ suspicious of their loyalty. Palestinian BRUSSELS, 14 MARCH 2012 (EXCERPTS). citizens’ trust in the state plummeted af- ter Israeli security forces killed thirteen The International Crisis Group’s of their own during protests in Octo- (ICG) 119th Middle East Report, titled ber 2000. A rapid succession of con- “Back to Basics: Israel’s Arab Minor- frontations—the 2006 war in Lebanon; ity and the Israeli-Palestinian Con!ict,” 2008–2009 Gaza war; and 2010 bloody runs to 45 pages. The excerpts below are Israeli raid on the aid !otilla to Gaza— from the Executive Summary and Sec- further deepened mistrust, galvaniz- tion III, “Palestinians in Israel and the ing the perception among Israeli Jews Peace Process.” Not included are long that Palestinian citizens had embraced background sections covering the de- their sworn adversaries. Among Arabs, teriorating situation of the Palestinian it reinforced the sense that they had no citizens of Israel since the second inti- place in Israel. Several have been ar- fada broke out in September 2000, and rested on charges of abetting terrorist a mapping of the political trends, move- activity. Meanwhile, the crisis of the Pal- ments, parties, and other political actors estinian national movement—divided, within the Arab minority. The extensive adrift, and in search of a new strategy— footnotes have been eliminated to save has opened up political space for Israel’s space. -

The “Status Quo” on the Temple Mount

No. 604 November-December, 2014 http://jcpa.org/article/status-quo-on-temple-mount/ The “Status Quo” on the Temple Mount Nadav Shragai . Since July 2, 2014, an upsurge in Palestinian violence has been occurring in Jerusalem, and the number of attacks on Israelis has escalated. The Temple Mount is one of the focal points of this renewed conflict. The Temple Mount, site of the ancient First and Second Temples, is the holiest place in the world for the Jewish people. Two Muslim shrines – the Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock – stand on it today, and it is the third holiest place for Muslims. The recent events on the Temple Mount are instigated by operatives of Hamas and the Northern Branch of the Islamic Movement in Israel (both of which are part of the Muslim Brotherhood network) and Mahmoud Abbas’ Fatah movement. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and other government officials have repeatedly stated that there will be no change in the status quo on the Temple Mount, and Jewish prayer will not be permitted there. In July 1967, Israel extended Israeli law to east Jerusalem, including the Old City and the Temple Mount, which came under Israeli sovereignty. In granting Jews the right to visit the Temple Mount, Moshe Dayan sought to mitigate the power of Jewish demands for organized worship and religious control at the site. In granting administrative control to Muslims on the Temple Mount, he believed he was mitigating the power of the site as a center for Palestinian nationalism. 1 . However, the old status quo has been greatly degraded, increasing Muslim control and status on the Mount and greatly undermining the status of Jews and the State of Israel on the Mount.