The Judicial System of Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Legal Terms Used in Scottish Court Procedure, Neil Kelly Partner

Legal Terms Used in Scottish Court Procedure, Neil Kelly Partner, MacRoberts Many recent reported adjudication decisions have come from the Scottish Courts. Therefore, as part of the case notes update, we have included a brief explanation of some of the Scottish Court procedures. There are noted below certain legal terms used in Scottish Court Procedure with a brief explanation of them. This is done in an attempt to give some readers a better understanding of some of the terms used in the Scottish cases highlighted on this web-site. 1. Action: Legal proceedings before a Court in Scotland initiated by Initial Writ or Summons. 2. Adjustment (of Pleadings): The process by which a party changes its written pleadings during the period allowed by the Court for adjustment. 3. Amendment (of Pleadings): The process by which a party changes its written pleadings after the period for adjustment has expired. Amendment requires leave of the Court. 4. Appeal to Sheriff Principal: In certain circumstances an appeal may be taken from a decision of a Sheriff to the Sheriff Principal. In some cases leave of the Sheriff is required. 5. Appeal to Court of Session: In certain circumstances an appeal may be taken from a decision of a Sheriff directly to the Court of Session or from a decision of the Sheriff Principal to the Court of Session. Such an appeal may require leave of the Sheriff or Sheriff Principal who pronounced the decision. Such an appeal will be heard by the Inner House of the Court of Session. 6. Arrestment: The process of diligence under which a Pursuer (or Defender in a counterclaim) can obtain security for a claim by freezing moveable (personal) property of the debtor in the hands of third parties e.g. -

Outer House, Court of Session

OUTER HOUSE, COURT OF SESSION [2018] CSOH 61 P1293/17 OPINION OF LORD BOYD OF DUNCANSBY in the Petition of ANDREW WIGHTMAN MSP AND OTHERS Petitioners TOM BRAKE MP AND CHRIS LESLIE MP, Additional Parties for Judicial Review against SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EXITING THE EUROPEAN UNION Respondents Petitioners: O’Neill QC, Welsh; Balfour + Manson LLP Additional Parties: M Ross QC; Harper Macleod LLP Respondents: Johnston QC, Webster; Office of the Advocate General 8 June 2018 Introduction [1] On 23 June 2016 the people of the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union. Following the Supreme Court case of Miller (R (Miller and another) v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union [2018] AC 61) the United Kingdom Parliament enacted the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Act 2017 authorising the Prime Minister to notify under article 50(2) of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) the UK’s intention to 2 withdraw from the European Union. On 29 March 2017 the Prime Minister, in a letter addressed to the European Council (EC), gave notice under article 50(2) of the TEU (the “article 50 notification”) of the UK’s intention to withdraw. [2] Can that notice be unilaterally revoked by the UK acting in good faith such that the United Kingdom could continue to be a member of the European Union after 29 March 2019 on the same terms and conditions as it presently enjoys? That is the question which the petitioners and the additional parties wish answered. [3] All but one of the petitioners is an elected representative. -

162 INTERNATIONAL LAWYER Long Before the 1957 Law, Indigent

162 INTERNATIONAL LAWYER Long before the 1957 law, indigent litigants could obtain exemption from judicial fees payable for actions in courts. The presently effective statute, 53 which dates from 1936, is part of the Code of Civil Procedure; it regulates in detail the bases on which an indigent litigant can obtain a waiver of court costs. A person who seeks legal aid either gratuitously or at a reduced rate initiates his request by obtaining from the Municipality a form, which must be filled out personally by the applicant, setting forth the financial situation on which he bases his claim that he is unable to obtain needed assistance via his own resources. Information furnished on the form is checked by the Municipality, and the application is then submitted to the consultation bureau for processing and determination of the legal aid which will be furnished. Information furnished by the applicant is further subject to examination by the court which may seek confirmation of the financial condition alleged from the tax authorities. 2. CRIMINAL MATTERS Counsel has always been available to indigent defendants in criminal matters involving a felony. 154 Within the jurisdiction of each court of first instance, a court-appointed Council for Legal Assistance functions in crim- inal matters, consisting of at least three attorneys. The Council assigns attorneys to indigent defendants in criminal matters as provided in the Code of Criminal Procedure and further as the Council may deem fit. Each defendant in provisional custody must be assigned counsel by the president of the court before which the matter will be adjudicated. -

British Institute of International and Comparative Law

BRITISH INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AND COMPARATIVE LAW PROJECT REFERENCE: JLS/2006/FPC/21 – 30-CE-00914760055 THE EFFECT IN THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY OF JUDGMENTS IN CIVIL AND COMMERCIAL MATTERS: RECOGNITION, RES JUDICATA AND ABUSE OF PROCESS Project Advisory Board: The Rt Hon Sir Francis Jacobs KCMG QC (chair); Lord Mance; Mr David Anderson QC; Dr Peter Barnett; Mr Peter Beaton; Professor Adrian Briggs; Professor Burkhard Hess; Mr Adam Johnson; Mr Alex Layton QC; Professor Paul Oberhammer; Professor Rolf Stürner; Ms Mona Vaswani; Professor Rhonda Wasserman Project National Rapporteurs: Mr Peter Beaton (Scotland); Professor Alegría Borrás (Spain); Mr Andrew Dickinson (England and Wales); Mr Javier Areste Gonzalez (Spain – Assistant Rapporteur); Mr Christian Heinze (Germany); Professor Lars Heuman (Sweden); Mr Urs Hoffmann-Nowotny (Switzerland – Assistant Rapporteur); Professor Emmanuel Jeuland (France); Professor Paul Oberhammer (Switzerland); Mr Jonas Olsson (Sweden – Assistant Rapporteur); Mr Mikael Pauli (Sweden – Assistant Rapporteur); Dr Norel Rosner (Romania); Ms Justine Stefanelli (United States); Mr Jacob van de Velden (Netherlands) Project Director: Jacob van de Velden Project Research Fellow: Justine Stefanelli Project Consultant: Andrew Dickinson Project Research Assistants: Elina Konstantinidou and Daniel Vasbeck 1 QUESTIONNAIRE The Effect in the European Community of Judgments in Civil and Commercial Matters: Recognition, Res Judicata and Abuse of Process Instructions to National Rapporteurs Please use the following questions to describe the current position in the country for which you have been appointed as National Rapporteur. Please respond to the following questions as fully as possible, with appropriate reference to, and quotation of, supporting authority (e.g. case law and, where appropriate, the views of legal writers). -

PE1458/JJJ Submission from the Petitioner, 29 November 2017 A

PE1458/JJJ Submission from the Petitioner, 29 November 2017 A further development of interest to members with regards to the Register of Judicial Recusals – created by former Lord President Lord Brian Gill as a result of this petition in April 2014. During the creation of the Register of Judicial Recusals in 2014, some 400 plus members of the judiciary – Justices of the Peace – were excluded from the register for no apparent reason. Recent communications with the Judicial Office and further media interest in the petition1 has prompted the Judicial Office to finally include Justices of the Peace in the Register of Judicial Recusals – with a start date of January 2018. This follows an earlier development after Lord Carloway gave his evidence to the Committee, where the Judicial Office agreed to publish a wider range of details regarding judicial recusals2. A copy of the revised recusal form for members of the Judiciary has been provided by the Judicial Office and is submitted for members interest. Additional enquiries with the Judicial Office and further media interest3 on the issue of Tribunals which come under the Scottish Courts & Tribunals Service (SCTS) and Judicial Office jurisdiction has produced a further result in the Judicial Office agreeing to publish a register of Tribunal recusals. I urge members to seek clarification from the Judicial Office and Lord President on why Justices of the Peace, who now comprise around 500 members of the judiciary in Scotland, were excluded from the recusals register until now – as their omission from the recusals register has left a distorted picture of judicial recusals in Scotland. -

The Scottish Bar: the Evolution of the Faculty of Advocates in Its Historical Setting, 28 La

Louisiana Law Review Volume 28 | Number 2 February 1968 The cottS ish Bar: The volutE ion of the Faculty of Advocates in Its Historical Setting Nan Wilson Repository Citation Nan Wilson, The Scottish Bar: The Evolution of the Faculty of Advocates in Its Historical Setting, 28 La. L. Rev. (1968) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol28/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SCOTTISH BAR: THE EVOLUTION OF THE FACULTY OF ADVOCATES IN ITS HISTORICAL SOCIAL SETTING Nan Wilson* Although the expression "advocate" is used in early Scottish statutes such as the Act of 1424, c. 45, which provided for legal aid to the indigent, the Faculty of Advocates as such dates from 1532 when the Court of Session was constituted as a College of Justice. Before this time, though friends of litigants could appear as unpaid amateurs, there had, of course, been professional lawyers, lay and ecclesiastical, variously described as "fore- speakers," procurators and prolocutors. The functions of advo- cate and solicitor had not yet been differentiated, though the notary had been for historical reasons. The law teacher was then essentially an ecclesiastic. As early as 1455, a distinctive costume (a green tabard) for pleaders was prescribed by Act of Parliament.' Between 1496 and 1501, at least a dozen pleaders can be identified as in extensive practice before the highest courts, and procurators appeared regularly in the Sheriff Courts.2 The position of notary also flourished in Scotland as on the Continent, though from 1469 the King asserted the exclusive right to appoint candidates for that branch of legal practice. -

2011 No. 430 HIGH COURT of JUSTICIARY SHERIFF COURT

SCOTTISH STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2011 No. 430 HIGH COURT OF JUSTICIARY SHERIFF COURT JUSTICE OF THE PEACE COURT Act of Adjournal (Amendment of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995) (Refixing diets) 2011 Made - - - - 6th December 2011 Laid before the Scottish Parliament 8th December 2011 Coming into force - - 30th January 2012 The Lord Justice General, the Lord Justice Clerk and the Lords Commissioners of Justiciary, under and by virtue of the powers conferred on them by section 305 of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995(a) and of all other powers enabling them in that behalf do hereby enact and declare: Citation, commencement etc. 1.—(1) This Act of Adjournal may be cited as the Act of Adjournal (Amendment of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995) (Refixing diets) 2011. (2) It comes into force on 30th January 2012. (3) A certified copy of this Act of Adjournal is to be inserted in the Books of Adjournal. Amendment of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995: refixing diets 2.—(1) The Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 is amended in accordance with subparagraphs (2) to (5). (2) After section 75B (refixing diets)(b) insert— “75C Refixing diets: non-suitable days (1) Where in any proceedings on indictment any diet has been fixed for a day which is no longer suitable to the court, it may, of its own accord, at any time before that diet— (a) discharge the diet; and (a) 1995 c.46. (b) Section 75B was inserted by section 39 of the Criminal Proceedings etc. (Reform) (Scotland) Act 2007 (asp 6). (b) fix a new diet for a date earlier or later than that for which the discharged diet was fixed. -

Public Records (Scotland) Act 1937

DISCLAIMER: As Member States provide national legislations, hyperlinks and explanatory notes (if any), UNESCO does not guarantee their accuracy, nor their up-dating on this web site, and is not liable for any incorrect information. COPYRIGHT: All rights reserved.This information may be used only for research, educational, legal and non- commercial purposes, with acknowledgement of UNESCO Cultural Heritage Laws Database as the source (© UNESCO). Public Records – Scotland- Act, 1937 1937 (1 Edw. 8 & 1 Geo. 6.) CHAPTER 43. [6th July 1937.] An Act to make better provision for the preservation, care and custody of the Public Records of Scotland, and for the discharge of the duties of Principal Extractor of the Court of Session. BE it enacted by the King's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:— PART I COURT RECORDS; 1. High Court and Court of Session records. (1) The records of the High Court of Justiciary and of the Court of Session shall be transmitted to the Keeper of the Registers and Records of Scotland (hereinafter referred to as the Keeper) at such times, and subject to such conditions, as may respectively be prescribed by Act of Adjournal or Act of Sederunt. (2) An Act of Adjournal or an Act of Sederunt under the foregoing subsection may fix different times and conditions of transmission for different classes of records and may make provision for re-transmission of records to the Court when such re-transmission is necessary for the purpose of any proceedings before the Court, and for the return to the Keeper of records so re-transmitted as soon as may be after they have ceased to be required for such purpose. -

![[2019] CSIH 54 A199/2018 Lord Justice Clerk Lord Drummond Young Lord Malcolm](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0407/2019-csih-54-a199-2018-lord-justice-clerk-lord-drummond-young-lord-malcolm-1070407.webp)

[2019] CSIH 54 A199/2018 Lord Justice Clerk Lord Drummond Young Lord Malcolm

SECOND DIVISION, INNER HOUSE, COURT OF SESSION [2019] CSIH 54 A199/2018 Lord Justice Clerk Lord Drummond Young Lord Malcolm OPINION OF THE COURT delivered by LADY DORRIAN, the LORD JUSTICE CLERK in the APPEAL by SHAKAR OMAR ALI Pursuer and Reclaimer against (1) SERCO LIMITED, (2) COMPASS SNI LIMITED AND (3) THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT Defenders and Respondents Pursuer and Reclaimer: Bovey QC, Dailly (sol adv); Drummond Miller LLP 1st and 2nd Defenders and Respondents: Connal QC (sol adv), Byrne; Pinsent Masons LLP 3rd Defender and Respondent: McIlvride QC, Gill; Morton Fraser Intervener: The Scottish Commission for Human Rights 13 November 2019 Background [1] The appellant is a failed asylum seeker. A claim made in her own right was withdrawn, and a subsequent claim made which was dependant on a claim made by her husband. That claim was refused and appeal rights were exhausted by 2 November 2017, at which date neither the appellant nor her husband had an extant claim for asylum. During 2 the currency of their asylum claims the appellant and her husband had been provided with temporary accommodation in accordance with the obligations incumbent upon the Secretary of State for the Home Department in terms of section 95 of the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999 (“the 1999 Act”). That accommodation had been provided on behalf of the Secretary of State by the first respondent, Serco Limited, and its subsidiary the second respondent (for convenience referred to jointly as “Serco”) under a contract between the first respondent and the Secretary of State. -

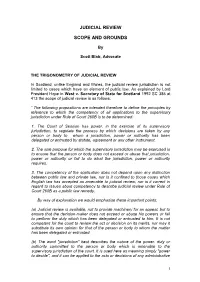

Judicial Review Scope and Grounds

JUDICIAL REVIEW SCOPE AND GROUNDS By Scott Blair, Advocate THE TRIGONOMETRY OF JUDICIAL REVIEW In Scotland, unlike England and Wales, the judicial review jurisdiction is not limited to cases which have an element of public law. As explained by Lord President Hope in West v. Secretary of State for Scotland 1992 SC 385 at 413 the scope of judicial review is as follows: “ The following propositions are intended therefore to define the principles by reference to which the competency of all applications to the supervisory jurisdiction under Rule of Court 260B is to be determined: 1. The Court of Session has power, in the exercise of its supervisory jurisdiction, to regulate the process by which decisions are taken by any person or body to whom a jurisdiction, power or authority has been delegated or entrusted by statute, agreement or any other instrument. 2. The sole purpose for which the supervisory jurisdiction may be exercised is to ensure that the person or body does not exceed or abuse that jurisdiction, power or authority or fail to do what the jurisdiction, power or authority requires. 3. The competency of the application does not depend upon any distinction between public law and private law, nor is it confined to those cases which English law has accepted as amenable to judicial review, nor is it correct in regard to issues about competency to describe judicial review under Rule of Court 260B as a public law remedy. By way of explanation we would emphasise these important points: (a) Judicial review is available, not to provide machinery for an appeal, but to ensure that the decision-maker does not exceed or abuse his powers or fail to perform the duty which has been delegated or entrusted to him. -

385 WEST V. SECRETARY of STATE for SCOTLAND Apr. 23

s.c. WEST V. SECRETARY OF STAT E FOR SCOTLAND 385 WEST v. SECRETARY OF STATE FOR SCOTLAND No. 33. FIRST DIVISION. Apr. 23, 1992. Lord Weir. WILLIAM LAURISTON WEST, Petitioner (Reclaimer). — Mackinnon. THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR SCOTLAND (on behalf of the Scottish Prison Service), Respondent. — Clarke, Q.C., Reed. Administrative law—Practice—Judicial review — Competency — Prison officer refused discretionary reimbursement of removal expenses — Scope of supervisory jurisdiction of Court of Session—Whether exercise of discretion by Scottish Prison Service open to judicial review — Whether criteria for exercise of supervisory jurisdiction included requirement that "public law " element be present—Rules of Court 1965, rule 260B.1 The petitioner, a serving prison officer, was transferred from a young offenders institution to a prison. Under his conditions of service with his employers, the Scottish Prison Service, he was regarded as "mobile staff and liable to be transferred compulsorily to any prison service establishment in Scotland. Provision was made in the conditions of service for the reimbursement to staff of inter alia removal expenses. As a result of his transfer, the petitioner required to move house but was thereafter informed by his employers that his removal expenses would not be reimbursed. He then presented a petition to the Court of Session for judicial review of the prison service's decision, on the ground that the refusal was an unreasonable exercise of its discretion, for reduction of its decision, and declarator that he was entitled to reimbursement of his removal expenses and damages. The respondent, the Secretary of State for Scotland, lodged answers on behalf of the prison service, arguing that the petition was incompetent and irrelevant. -

The Salem Witch Trials from a Legal Perspective: the Importance of Spectral Evidence Reconsidered

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1984 The Salem Witch Trials from a Legal Perspective: The Importance of Spectral Evidence Reconsidered Susan Kay Ocksreider College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Law Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Ocksreider, Susan Kay, "The Salem Witch Trials from a Legal Perspective: The Importance of Spectral Evidence Reconsidered" (1984). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625278. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-7p31-h828 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SALEM WITCH TRIALS FROM A LEGAL PERSPECTIVE; THE IMPORTANCE OF SPECTRAL EVIDENCE RECONSIDERED A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of Williams and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Susan K. Ocksreider 1984 ProQuest Number: 10626505 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10626505 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017).