In Sight: a Review of the Visual Impairment Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

College News October 2018

30 YEARS 1988 - 2018 QUARTERLY MAGAZINE OCTOBER EDITION 2018 Congratulations to this year’s Honorary Fellows, Professor Harminder Dua, Miss Marcia Zondervan and the diplomates receiving their award at the RCOphth Admissions Ceremony in September. PAGE 4 A SAS perspective Jugnoo Rahi Trainee Knowledge PAGE 6 New PAGE 15 New PAGE 18 How to to the NHS Chair, Academic mix research with subcommittee clinical training college news Dear fellow members, “Treating clinicians can lawfully choose Avastin for ophthalmic use on grounds of cost” Contents The 21st of September 2018 will live long in the memory of those who have campaigned 3 Awards galore! to be allowed to use Avastin (bevacizumab) 5 2018 Admissions as treatment for wet age-related macular Ceremony degeneration (ARMD). The landmark ruling by 6 New to the NHS - A Mrs Justice Whipple has brought clarity to the SAS Perspective interpretation of the national and European 7 Focus Managing legislation and should be read in full by all refractive surprise ophthalmologists. The College has issued a briefing note via Eye- 11 Museum Piece Mail to help answer some of the comments Births and Books in Whilst some may consider this a victory and concerns raised by members and I wish Ophthalmology 1818 over ‘Big Pharma’, we must not forget that members to continue to contribute to the 15 Jugnoo Rahi pharmaceutical companies are responsible discussions around Avastin. - New Academic for the development of the drugs we now use subcommittee chair to prevent blindness. It is essential that we Please do contact me at president@rcophth. 17 Ophthalmologists in recognise their vital role in eye health and ac.uk and I will do my best to answer your Training continue to work closely with them in future. -

Report on Disabled People's Training

Research Report No 243 Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Residential Training for Disabled People Kevin Maton and Kate Smyth with Steve Broome and Paul Field UK Research Partnership Ltd The Views expressed in this report are the authors' and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department for Education and Employment. © Crown Copyright 2000. Published with the permission of DfEE on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office. Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to The Crown Copyright Unit, Her Majesty's Stationery Office, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ. ISBN 1 84185 409 3 DECEMBER 2000 i 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. METHODOLOGY 3 2.1 Work programme 3 2.2 Basis of the research 3 3. THE CONTEXT 5 3.1 Disabled people in the workforce 5 3.2 Introduction 5 3.3 National Labour Force Survey – details 6 3.4 DfEE baseline disability survey 10 3.5 Government strategy for employment and training provision for disabled people 11 3.6 The residential training programme and training providers 13 4. TRAINING PROVIDERS AND PROVISION 15 4.1 The Residential Training Providers 15 4.2 Home location of trainees 18 4.3 The process – accessing residential training providers 21 4.4 Process of accessing training provision – the impact on individuals 26 4.5 Residential Training Providers – issues affecting trainees 31 4.6 Key findings and recommendations 47 5. CLIENT GROUP 53 5.1 Introduction 53 5.2 Characteristics of the client group 53 5.3 Key findings 63 6. TRAINEE SATISFACTION 65 i 6.1 Views of current trainees of their training programme 65 6.2 View of training programmes 67 6.3 Improving employment opportunities – outcomes from current trainees 72 6.4 Benefits of residential training 74 6.5 Key findings 75 7. -

UK Eye Care Services Project Phase One: Systematic Review of the Organisation of UK Eye Care Services

UK Eye Care Services Project Phase One: Systematic Review of the Organisation of UK Eye Care Services University of Warwick September 2010 (Revised February 2011) Dr Carol Hawley Helen Albrow Dr Jackie Sturt Lynda Mason UK Eye Care Services Project Contents Phase One: Systematic Review of the Organisation of UK Eye Care Services Study team i Acknowledgements i Glossary of abbreviations ii Executive Summary 1 1. Background to current organisation of UK eye care services 4 Devolution in Scotland and Wales 6 Global thinking surrounding eye care services and the UK response 8 Other ophthalmic roles 9 Generalisability of care pathways 11 Report Aim 11 2. Methods 12 2.1 Data searches 12 2.2 Data Extraction 14 3. Results 15 3.1 Report organisation 15 3.2 Summary of ‘black’ literature 17 Optometrists in primary care 18 Optometrists within the HES 19 Combined eye examination and referral initiatives for all eye conditions 22 Referral initiatives for all eye conditions 23 Referral quality and frequencies for all eye conditions 25 Glaucoma 28 Ocular Hypertension (OHT) 40 Cataract 41 Posterior Capsular Opacification 47 Diabetic Retinopathy (DR) 49 Blood Glucose screening 60 Optometric Prescribing 61 Low Vision Services 64 Paediatric eye care services 67 Melanoma 71 Flashes and floaters 72 Critique of the COSI concept (Community Optometrists with a Special Interest) 74 Optometric technological comparison studies 75 4. Conclusions from the literature 76 5. References 78 UK Eye Care Services Project Appendices Phase One: Systematic Review of the Organisation -

Crafting Alliances

05-Wei-45241.qxd 2/14/2007 5:16 PM Page 191 CHAPTER 5 Crafting Alliances egardless of how successful a social enterprise is at mobilizing funds, most R organizations will inevitably face resource and capacity constraints as a limiting factor to achieving their mission. The resources that any single organi- zation brings to bear on a social problem are often dwarfed by the magnitude and complexity of most social problems. Thus, social entrepreneurs often pursue alliance approaches as a means to mobilizing resources, financial and nonfinan- cial, from the larger context and beyond their own organizational boundaries, to achieve increased mission impact. Social enterprise alliances among nonprofits, nonprofits and business, nonprofits and government, and even across all sectors in the form of tripartite alliances between nonprofit, government, and business have become increasingly common in recent years. Because alliances capitalize on the resources and capacities of more than one organization and capture syn- ergies that would otherwise often go unrealized, they have the potential to gen- erate mission impact far beyond what the individual contributors could achieve independently. This chapter first describes some alliance trends in the social sec- tor and illustrates them with case examples. Next, we introduce a conceptual framework that can be helpful for developing an alliance strategy. Finally, we briefly introduce the chapter’s two case studies, which offer readers an opportu- nity for in-depth analysis of a range of alliance approaches. ALLIANCE TRENDS Increased Competition Increased competition due to a growing number of nonprofits coupled with recent overall declines in social sector funding have contributed to a dramatic 191 05-Wei-45241.qxd 2/14/2007 5:16 PM Page 192 192 Entrepreneurship in the Social Sector increase in the number and form of social enterprise alliances. -

Fight for Sight Is the UK's Largest Charity Funding Pioneering Eye

Fight for Sight is the UK’s largest charity funding pioneering eye research since 1965. Our mission Fight for Sight funds pioneering research to prevent sight loss and treat eye disease. Our vision A future everyone can see. Fight£3.3m for Sight committed to research in 2017/18 Fight£8m for Sight commitment to active research projects Number of active research projects 166 Number of funded institutions 49 5 49 49 2 49 7 49 3 49 3 49 2 49 7 49 1 49 10 49 5 49 4 Numbers of patients in clinical studies funded by Fight for Sight Number16,230 of patients Number87 of studies recruited into NIHR on the NIHR CRN supported studies funded portfolio funded partly partly or wholly by or wholly by Fight for Sight Fight for Sight between between April 2008 April 2008 and and January 2018 January 2018 Number71 of sites Number23 of studies from which NIHR has open on the NIHR recruited participants for CRN portfolio studies funded partly or funded partly or wholly wholly by Fight for Sight by Fight for Sight between April 2008 as of January 2018 and January 2018 National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network (CRN) Charity partners Fight for Sight is very pleased to be collaborating with other charities in the sector. Fight for Sight is the UK’s largest charity funding pioneering eye research since 1965. Estimated prevalence of main eye diseases in the UK Age-related macular degeneration 600,000 people Glaucoma 500,000 people Cataract 500,000 people Diabetic retinopathy 144,000 people How many people fear losing their sight? of25% the adult population are not having an eye test of people78% stated every 2E years. -

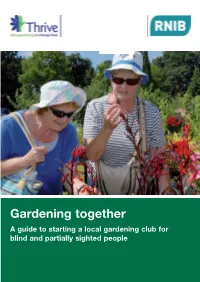

Gardening Together a Guide to Starting a Local Gardening Club for Blind and Partially Sighted People Introduction

Gardening together A guide to starting a local gardening club for blind and partially sighted people Introduction Starting a club from scratch need not be daunting. This guide draws upon the experiences of gardeners and professionals who have successfully launched their own clubs and gives ideas that you might need to take into consideration. It also gives you contact details of other organisations and sources of information that could be useful. The advice is aimed at people who want to start a club. It will also be useful for groups and professionals who work with visually impaired people. Not all the information will be relevant to everyone. Areas covered are: recruiting members; publicity; meeting place; programme ideas; finances; transport; supporters and volunteers; other support; legalities; health and safety; and development ideas. Throughout the guide you will find top tips from people who have started local clubs recently; thanks for these to Mick Evans and Alan Thorpe from the Rotherham BANCA club, Judy Shaw from the Greenshoots club in York and Mark Smith from Gardeneyes in Norwich. You will also find signposts, including contact details, to other organisations that may be able to help you. These are headed Help. “Anyone should have a go, we are only a small group but we are all getting enjoyment out of it… people get satisfaction out of seeing something grow.” Judy Shaw, Greenshoots club 2 Contents Who is the club for? 4 How will you let people know about the club? 6 What will you do at the club? 7 Where will you meet? 9 How will your members get to the club? 13 Who will do what? 14 What about money? 18 What about the legal side? 21 What about health and safety? 23 What other support is there? 25 Appendix 1: A sample constitution 28 Appendix 2: Notes on guiding 34 Appendix 3: Sample risk assessment 36 Appendix 4: Criminal Records Bureau (CRB) clearance 38 3 Who is the club for? Your first task is to establish that there is sufficient interest in your local area. -

Eye Research Charity Looking for Pioneering Researchers in Scotland Fight for Sight Partners with Chief Scientist Office to Fund Research in Scotland

Immediate release Eye research charity looking for pioneering researchers in Scotland Fight for Sight partners with Chief Scientist Office to fund research in Scotland Fight for Sight, the UK’s leading eye research charity, has partnered with the Scottish Government’s Chief Scientist Office (CSO) to help address age-related eye diseases. The charity is calling for research applications from Scottish based researchers for a grant of up to £200,000 for up to three years. The grant will support research to help address age- related eye diseases and conditions as well as projects focusing on the association of visual impairment with other long-term conditions, such as dementia, stroke or diabetes. The closing date for Fight for Sight/ CSO Project grant applications is 5pm on 1 November 2017. Supporting Quote: Dr Alan McNair, Senior Research Manager at the Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office “CSO is delighted to partner with Fight for Sight in this exciting research funding initiative. Age related eye diseases can severely impact patients and those close to them. Research is essential if we are to develop a better understanding of the impact of these conditions and develop effective new treatments”. Michele Acton, Chief Executive of Fight for Sight “It is only through funding eye research that we will be able to address age-related sight loss. Partnering with the CSO will bring us closer to our goals to the benefit of people in Scotland and worldwide.” Online Resources: W: http://www.fightforsight.org.uk/apply-for-funding/funding-opportunities/fight-for-sight-cso- project-grant/ T: @fightforsightUK F: https://www.facebook.com/fightforsightuk ENDS About Fight for Sight 1. -

Birmingham and Solihull Eye Health Sight Loss Evidence Base

Birmingham and Solihull Eye Health and Sight Loss Evidence Base 2018 Date: October 2018 Produced by: West Midlands Local Eye Health Network (LEHN) and England Vision Strategy Copies in accessible formats are available from: [email protected] 1 The following organisations contributed to this evidence base: NHS England NHS Birmingham and Solihull Clinical Commissioning Group Birmingham VI Partnership RNIB Thomas Pocklington Trust University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust Sandwell and West Birmingham Hospitals NHS Trust Birmingham Local Optical Committee Birmingham Local Medical Committee Birmingham City Council Solihull Metropolitan Borough Council Solihull Local Optical Committee Solihull Local Medical Committee 2 Contents Executive Summary Evidence Base The picture of sight loss Prevalence of sight loss Public Health Outcomes Framework: sight loss indicators Costs associated with sight loss Groups at increased risk of sight loss Older people People from black and minority ethnic backgrounds People with learning disabilities People with dementia People who are deafblind Wellbeing consequences of sight loss Depression, social isolation and loneliness Poverty Falls Modifiable risk factors for sight loss Smoking Obesity Alcohol High blood pressure and stroke Diabetes Mapping the Sector Diagnosis and Treatment of Sight Loss Promoting eye health and preventing avoidable sight loss Sight tests and referrals - optometrists GP services Hospital based Community based Low vision services Assessment and rehabilitation Certificate -

A Practical Guide for Disabled People

HB6 A Practical Guide for Disabled People Where to find information, services and equipment Foreword We are pleased to introduce the latest edition of A Practical Guide for Disabled People. This guide is designed to provide you with accurate up-to-date information about your rights and the services you can use if you are a disabled person or you care for a disabled relative or friend. It should also be helpful to those working in services for disabled people and in voluntary organisations. The Government is committed to: – securing comprehensive and enforceable civil rights for disabled people – improving services for disabled people, taking into account their needs and wishes – and improving information about services. The guide gives information about services from Government departments and agencies, the NHS and local government, and voluntary organisations. It covers everyday needs such as money and housing as well as opportunities for holidays and leisure. It includes phone numbers and publications and a list of organisations.Audio cassette and Braille versions are also available. I hope that you will find it a practical source of useful information. John Hutton Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Health Margaret Hodge Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Employment and Equal Opportunities, Minister for Disabled People The Disability Discrimination Act The Disability Discrimination Act became law in November 1995 and many of its main provisions came into force on 2 December 1996.The Act has introduced new rights and measures aimed at ending the discrimination which many disabled people face. Disabled people now have new rights in the areas of employment; getting goods and services; and buying or renting property.Further rights of access to goods and services to protect disabled people from discrimination will be phased in. -

Section 1.14.08.02

Dimensions 2002 Annual Update of CAFs Top 500 Fundraising Charities Cathy Pharoah Dimensions 2002 Update of CAF’s Top 500 Fundraising Charities Cathy Pharoah © 2002 Charities Aid Foundation Published by Charities Aid Foundation Kings Hill, West Malling, Kent, ME19 4TA Tel +44 (0) 1732 520000 Fax +44 (0) 1732 520001 Web address http://www.CAFonline.org Editor Andrew Steeds Design and production Big Picture Interactive ISBN 1-85934–140-3 All rights reserved; no part of this work may be reproduced in any form, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission in writing from the publisher. The CAF research team Cathy Pharoah Catherine Walker Liz Goodey Michelle Graley Andrew Fisher Tel +44 (0) 1732 520125 E-mail [email protected] The author would like to thank Susan Jones and Fraser Wilson for collecting and preparing the data for this report. CAF’s top 500 fundraising charities 1999–2000 Cathy Pharoah The millennium bonus for charities? The evidence from this 1999–2000 set of top charity fundraising tables shows that charities may well have received a remarkable millennium bonus. Both the voluntary income and total income of CAF’s top 500 fundraising charities showed impressive real-terms increases, as people marked the end of the century through many special fundraising events and campaigns such as Children’s Promise. If this increase is indeed due to a wave of public sentiment at the turn of the century, it is clear today that the millennium would not be alone in riding a tide of public- spiritedness. Recent events have shown that, in times of disaster or public grief, people turn again and again to philanthropy as a way of expressing their feelings. -

Read the Guide to Services for People with Sight Loss

Norfolk Children and Community Services Guide to Services for People with Sight Loss 1 Adult Social Services www.norfolk.gov.uk Telephone: 0344 800 8020 Braille, audio or additional print versions of the booklet can be obtained from customer services If you have any comments or suggestions on the content or layout of this booklet, please let us know at: Sensory Support Unit Tel. 01603 224087 2 Contents Page Number Introduction Section 1 – What Help is Available Registration 7 Social Services Sensory Support 8 NNAB 10 Other Main Support Agencies 11 Section 2 – Everyday Living Independent Living Skills 15 Equipment and Adaptations to your home 15 Home Security 17 Gas and Electricity, Water 17 Telephone 18 Post 18 Shopping 19 Financial Affairs 19 Voting Rights 21 Home Maintenance 21 Housing Support 21 Day and Residential Care 22 Section 3 – Seeing Better Residual vision, Low vision clinics 23 3 Section 4 – Communication Reading 24 Listening 25 Transcription 28 Television 29 Writing 29 Computers 30 Section 5 – Education 31 Children 31 Further and Higher Education 32 Student Support 33 Finance Section 6 – Work and Employment Training Department of Works and Pensions 34 Self-employment 35 Help and Advice 35 Section 7 – Benefits, Concessions and Legislation List of Benefits and Concessions 37 Advice and Support 38 Equality Act 2010 40 Section 8 – Getting about Safely Mobility Training 41 Planning a Journey 42 Community Transport 43 Travel Concessions 43 Holidays 44 4 Section 9 – Leisure Art and Crafts, games, music 46 Sport 47 Social Clubs 48 -

The Passenger Experience

The passenger experience Key ways to make train services accessible for blind and partially sighted people RNIB Good practice guide “ I have been removed from a train for not having a ticket because I couldn’t see the ticket machine and the details of what ticket to buy. The general awareness of other people is poor; just because I don’t have a white stick and guide dog doesn’t mean I don’t have a disability.” Research respondent 2 Acknowledgements Acknowledgements We would like to thank the following people and organisations for their insight during the production of this guide: Chris Hagyard, Virgin Trains David Partington, Transport for Greater Manchester David Sindall, Association of Train Operating Companies Greg Lewis, Age UK James Grant, Transport for London Jocelyn Pearson, Passenger Focus Kirsty Monk, Southern Railway Lynn Watson, Thomas Pocklington Trust Neil Craig, First Great Western Niamh Connolly, NCBI – The National Sight Loss Agency Peter Osborne, European Blind Union Rebecca Fuller, Passenger Transport Executive Group 3 Contents Contents 6 Who should read this guide 8 Foreword 9 Industry support for this guide 9 Association of Train Operating Companies 9 Passenger Focus 9 Passenger Transport Executive Group 11 The case for an inclusive rail service 12 Business benefits 13 A better understanding of what passengers with sight problems actually see 15 The challenges passengers with sight loss face 17 Making services accessible 17 Quality customer service 20 Access to information 24 Booking assistance 25 Getting to the station