Completed, but Also the Turf, Sedge, Rushes, Reeds, Fish and Fowl of the Watery Fen and Marsh, All of Which Had Their Uses and a Value in the Market

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

81 Wolverhampton

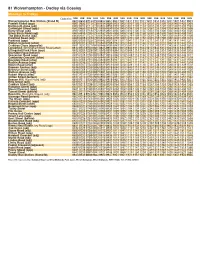

81 Wolverhampton - Dudley via Coseley Mondays to Fridays Operator: NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB Wolverhampton Bus Station (Stand B) 0600 0650 0715 0748 0832 0857 0931 1001 1031 1101 1131 1201 1231 1301 1331 1401 1431 1501 Powlett Street (opp) 0601 0652 0717 0750 0834 0859 0933 1003 1033 1103 1133 1203 1233 1303 1333 1403 1433 1503 Dartmouth Arms (adj) 0602 0652 0717 0750 0834 0859 0933 1003 1033 1103 1133 1203 1233 1303 1333 1403 1433 1503 Cartwright Street (opp) 0603 0653 0718 0751 0835 0900 0934 1004 1034 1104 1134 1204 1234 1304 1334 1404 1434 1505 Derry Street (adj) 0604 0654 0719 0752 0836 0901 0935 1005 1035 1105 1135 1205 1235 1305 1335 1405 1435 1505 Silver Birch Road (adj) 0605 0655 0720 0753 0837 0902 0936 1006 1036 1106 1136 1206 1236 1306 1336 1406 1436 1507 The Black Horse (adj) 0606 0657 0722 0755 0839 0904 0938 1008 1038 1108 1138 1208 1238 1308 1338 1408 1438 1508 Parkfield Road (adj) 0608 0658 0723 0756 0840 0905 0939 1009 1039 1109 1139 1209 1239 1309 1339 1409 1439 1510 Parkfield (opp) 0609 0700 0725 0758 0842 0907 0941 1011 1041 1111 1141 1211 1241 1311 1341 1411 1441 1511 Walton Crescent (after) 0610 0701 0726 0759 0843 0908 0942 1012 1042 1112 1142 1212 1242 1312 1342 1412 1442 1513 Crabtree Close (opposite) 0611 0702 0727 0800 0844 0909 0943 1013 1043 1113 1143 1213 1243 1313 1343 1413 1443 1514 Lanesfield, Birmingham New Road (after) 0612 0703 0728 0801 0845 0910 0944 1014 1044 1114 1144 1214 1244 1314 1344 1414 1444 1515 Ettingshall Park Farm (opp) 0612 0703 0728 0801 -

Agenda Annex

FORM 2 SHEFFIELD CITY COUNCILAgenda Annex Full Council Report of: Chief Executive ________________________________________________________________ Report to: Council ________________________________________________________________ Date: 4th March 2016 ________________________________________________________________ Subject: Polling District and Polling Place Review ________________________________________________________________ Author of Report: John Tomlinson 27 34091 ________________________________________________________________ Summary: Following the recent ward boundary changes the Authority is required to allocate Polling Districts and Polling Places. ________________________________________________________________ Reasons for Recommendations: The recommendations have been made dependent on the following criteria: 1. All polling districts must fall entirely within all Electoral areas is serves 2. A polling station should not have more than 2,500 electors allocated to it. ________________________________________________________________ Recommendations: The changes to polling district and polling place boundaries for Sheffield as set out in this report are approved. ________________________________________________________________ Background Papers: None Category of Report: OPEN Form 2 – Executive Report Page 1 January 2014 Statutory and Council Policy Checklist Financial Implications YES Cleared by: Pauline Wood Legal Implications YES Cleared by: Gillian Duckworth Equality of Opportunity Implications NO Cleared by: Tackling Health -

WEST Ridlng YORKSHIRE. FA

WEST RIDlNG YORKSHIRE. FA. a . Turner Thomas, .Abbey farm, Wath- Valentine John, Woodhouse, Stainton, Wade Mrs. A. Thurgoland ball, Sheffid upon-Dearne, Rotherham Rotherham Wade C. Booth stead, Warley, Halifax Turner Thoma_~~; .Alllwark, Rotherham Vardy Philip Geo. Park bead, Ecclesall Wade Edwin, 276 tlticket la. Bradford Turnel' Thos. Howgill; Sedbetgli R.8.0 Bierlow, Sheffield Wade Francis, Silsden mobr, Leeds TnrnerT.8onderlandst<.T~khl.Rothrhm Varley Abraham, Grassington, 8kipton Wade John, Bradshaw lane, Halifax TornerTho& Elslin, Svkehou8e, -8elbv Variey Benjamin, Gargrave, Leeds Wade Jn. High a~h, Pannal, Harrogat~ Turrter Wm. Farnley Tyos, H uddersfl.d V arley Geo. Terrr ple,Tem pie H urst,Selhy Wade J. Bull ho. Tburlstone, Sheffield Turner Wm. Grindleton, Clitheroe Varley James,Mixenden t~tones, Halifax Wade Joseph, 301 Rooley lane, Bradford Turner Wm. New hall, Rathmell,Settle Varley Joseph, Hoo hole,Mytholmroyd, Wade Mrs. Martba, Edge,Silsden, Leeds Turner Wm. Saville house., Hazlehead, Manchester Wade Robert, Kirkgate, Sil.sden, Leeds Sheffield I Varley Mrs. 1\fary, Great Heck, Selby Wade Robert, Silsden moor, Leeds Turner William, Shepley, Huddersfield Varley Rohert, Cononley, Leeds Wade Miss 8atrah A. Pannal, Harrogate Turner William,.Woodhouse, S!Jeffield VarleySl. G:reyston~s, Ovenden,Ralifax Wade Sykes, Balne, Selby Turner Wm. C. Stainton, Rotberharn Varley Thomas, West Marton, l:5kipton Wade T. High royd, Rang-e bank,Ifalifx Turner WilliamHenry,UpperBallbents, Varley Waiter, Melrham, Huddersfield Wade TltoruiUI Edwin, Wike, Leeds ?.Ieltham, Huddersfield Varley Wm. Barwick-in-Elmet, Leeds Wade William, Rufforth, York Turpla Mrs. Ann, Embsay, Sklpton Varley Wm. Hagg~, Colton, Tadcaster Waddington Henry, High Coates~ Turpin W. Twisletoningleton ,Carnforth Vaughton George, Oxspring, Sheffield Wilsden, Bingley Turr Gervas, Button, Doncaster VauseEdwd.Hardwick,Aston,Rotherhm Wadsworth Alex. -

Bradfield: the Eleven Guide-Stoops Walk

THE ELEVEN GUIDE STOOPS OF BRADFIELD A 17 ½ mile Anytime Winter Challenge Walk This is a hilly walk with 2,989 ft of climbing, very scenic and mainly on quiet roads designed for those winter months as an alternative to wading through mud. It can of course be attempted at any time of year and indeed, there are 3 footpath alternatives (shown in red) for purists or those averse to road walking. These footpath alternatives are attractive and do not add any extra mileage. I have counted at least a dozen horse troughs by the roadsides, indicating that apart from a layer of tarmac, these byways have changed little since the invention of the petrol engine. There must also be a record number of seats on this route, most with extensive views – well done Bradfield Parish Council. I hope you will find the walk full of interest as you discover the 11 guide stoops of the Parish of Bradfield, reputedly the second largest in England. I cannot, however, claim all the credit for this walk – the inspiration was a fascinating booklet entitled The Guide Stoops of the Dark Peak, published and printed privately by Howard Smith. The reason I took a walk to seek out these guide stoops for myself was due entirely to the foot and mouth epidemic of 2002 when, of course, footpaths were out of bounds. What are Guide Stoops? These are the earliest form of signposts which each Parish had the responsibility to maintain. They date from the 18 th and 19 th centuries and were usually carved from gritstone. -

DEATH on the HOME FRONT Pam Brooke

DEATH ON THE HOME FRONT Pam Brooke Much has been written about the Military Service Act and the operation of Tribunals however this has mostly focused on the outcome for conscientious objectors and little has been written about those who sought exemption on other grounds.1 One particularly tragic case from the Colne Valley illustrates the wide repercussions that the refusal of one man’s application for exemption had on both his family and the wider community. On Wednesday 28 November 1916, at Slaithwaite Town Hall, 62-year-old James Shaw, blacksmith and hill farmer appeared before the local Tribunal to request an extension to his son’s Exemption Certificate. Charles, aged 28, he said, was his only son and worked with him in the blacksmith shop and on the farm. Depicting himself to be ‘a poor talker’ James presented his case in a written statement which the military representative described as ‘resembling a sermon’. In response James explained that he was a regular worshipper at Pole Moor Baptist Chapel, Scammonden.2 New Gate Farm cottage as seen today. Photo by the author. 1 Cyril Pearce, Comrades in Conscience: The story of an English community’s opposition to the Great War, 2nd Edition (Francis Boutle, London: 2014), p. 134 2 Colne Valley Guardian [hereafter CVG], 1 December 1916 1 The statement gave a detailed account of the circumstances justifying exemption: his son began to milk aged nine and farmed their 14 acres of land for 23 head of cattle – including a dairy, together with six more acres under the plough for food production. -

82 Wolverhampton

82 Wolverhampton - Dudley via Bilston, Coseley Mondays to Fridays Operator: NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB Wolverhampton Bus Station (Stand P) 0620 0655 0715 0735 0755 0815 0835 0900 0920 0940 1000 1020 1040 1100 1120 Moseley, Deansfield School (adj) 0629 0704 0724 0746 0806 0826 0846 0910 0930 0950 1010 1030 1050 1110 1130 Bilston, Bilston Bus Station (Stand G) ARR 0640 0717 0737 0801 0821 0841 0901 0924 0944 1004 1024 1044 1104 1124 1144 Bilston Bus Station (Stand G) DEP0600 0620 0643 0700 0720 0740 0802 0824 0844 0904 0927 0947 1007 1027 1047 1107 1127 1147 Wallbrook, Norton Crescent (adj) 0607 0627 0650 0707 0727 0747 0809 0832 0852 0912 0935 0955 1015 1035 1055 1115 1135 1155 Roseville, Vicarage Road (before) 0613 0633 0656 0713 0733 0753 0815 0838 0858 0918 0941 1001 1021 1041 1101 1121 1141 1201 Wrens Nest Estate, Parkes Hall Road (after) 0617 0637 0700 0717 0737 0757 0820 0843 0903 0923 0946 1006 1026 1046 1106 1126 1146 1206 Dudley Bus Station (Stand N) 0627 0647 0710 0728 0748 0808 0832 0855 0915 0934 0957 1017 1037 1057 1117 1137 1157 1217 Mondays to Fridays Operator: NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB NXB Wolverhampton Bus Station (Stand P) 1140 1200 1220 1240 1300 1320 1340 1400 1420 1440 1500 1523 1548 1613 1633 1653 1713 1733 Moseley, Deansfield School (adj) 1150 1210 1230 1250 1310 1330 1350 1410 1430 1450 1510 1533 1558 1623 1643 1703 1723 1743 Bilston, Bilston Bus Station (Stand G) ARR1204 1224 1244 1304 1324 1344 1404 1424 1444 1504 1524 1547 1612 -

217 Bibliography Primary Historical Sources 'Order Of

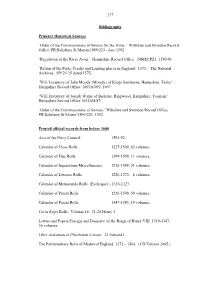

217 Bibliography Primary Historical Sources ‘Order of the Commissioners of Sewers for the Avon.’ Wiltshire and Swindon Record Office, PR/Salisbury St Martin/1899/223 - date 1592. ‘Regulation of the River Avon.’ Hampshire Record Office. 24M82/PZ3. 1590-91. ‘Return of the Ports, Creeks and Landing places in England. 1575.’ The National Archives. SP12/135 dated 1575. ‘Will, Inventory of John Moody (Mowdy) of Kings Somborne, Hampshire. Tailor.’ Hampshire Record Office. 1697A/099. 1697. ‘Will, Inventory of Joseph Warne of Bisterne, Ringwood, Hampshire, Yeoman.’ Hampshire Record Office 1632AD/87. ‘Order of the Commissioners of Sewers.’ Wiltshire and Swindon Record Office, PR/Salisbury St Martin/1899/223. 1592. Printed official records from before 1600 Acts of the Privy Council. 1591-92. Calendar of Close Rolls. 1227-1509, 62 volumes. Calendar of Fine Rolls. 1399-1509, 11 volumes. Calendar of Inquisitions Miscellaneous. 1216-1509, 21 volumes. Calendar of Liberate Rolls. 1226-1272, 6 volumes. Calendar of Memoranda Rolls. (Exchequer.) 1326-1327. Calendar of Patent Rolls. 1226-1509, 59 volumes. Calendar of Patent Rolls. 1547-1583, 19 volumes. Curia Regis Rolls. Volume 16. 21-26 Henry 3. Letters and Papers Foreign and Domestic of the Reign of Henry VIII. 1519-1547, 36 volumes. Liber Assisarum et Placitorum Corone. 23 Edward I. The Parliamentary Rolls of Medieval England. 1272 – 1504. (CD Version 2005.) 218 Placitorum in Domo Capitulari Westmonasteriensi Asservatorum Abbreviatio. (Abbreviatio Placitorum.) 1811. Rotuli Hundredorum. Volume I. Statutes at Large. 42 Volumes. Statutes of the Realm. 12 Volumes. Year Books of the Reign of King Edward the Third. Rolls Series. Year XIV. Printed offical records from after 1600 Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, of the Reign of Charles I. -

Report on Rare Birds in Great Britain in 1996 M

British Birds Established 1907; incorporating 'The Zoologist', established 1843 Report on rare birds in Great Britain in 1996 M. J. Rogers and the Rarities Committee with comments by K. D. Shaw and G. Walbridge A feature of the year was the invasion of Arctic Redpolls Carduelis homemanni and the associated mass of submitted material. Before circulations began, we feared the worst: a huge volume of contradictory reports with differing dates, places and numbers and probably a wide range of criteria used to identify the species. In the event, such fears were mostly unfounded. Several submissions were models of clarity and co-operation; we should like to thank those who got together to sort out often-confusing local situations and presented us with excellent files. Despite the numbers, we did not resort to nodding reports through: assessment remained strict, but the standard of description and observation was generally high (indeed, we were able to enjoy some of the best submissions ever). Even some rejections were 'near misses', usually through no fault of the observers. Occasionally, one or two suffered from inadequate documentation ('Looked just like bird A' not being quite good enough on its own). Having said that, we feel strongly that the figures presented in this report are minimal and a good many less-obvious individuals were probably passed over as 'Mealies' C. flammea flammea, often when people understandably felt more inclined to study the most distinctive Arctics. The general standard of submissions varies greatly. We strongly encourage individuality, but the use of at least the front of the standard record form helps. -

Leonard Bernstein's MASS

27 Season 2014-2015 Thursday, April 30, at 8:00 Friday, May 1, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, May 2, at 8:00 Sunday, May 3, at 2:00 Leonard Bernstein’s MASS: A Theatre Piece for Singers, Players, and Dancers* Conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin Texts from the liturgy of the Roman Mass Additional texts by Stephen Schwartz and Leonard Bernstein For a list of performing and creative artists please turn to page 30. *First complete Philadelphia Orchestra performances This program runs approximately 1 hour, 50 minutes, and will be performed without an intermission. These performances are made possible in part by the generous support of the William Penn Foundation and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Additional support has been provided by the Presser Foundation. 28 I. Devotions before Mass 1. Antiphon: Kyrie eleison 2. Hymn and Psalm: “A Simple Song” 3. Responsory: Alleluia II. First Introit (Rondo) 1. Prefatory Prayers 2. Thrice-Triple Canon: Dominus vobiscum III. Second Introit 1. In nomine Patris 2. Prayer for the Congregation (Chorale: “Almighty Father”) 3. Epiphany IV. Confession 1. Confiteor 2. Trope: “I Don’t Know” 3. Trope: “Easy” V. Meditation No. 1 VI. Gloria 1. Gloria tibi 2. Gloria in excelsis 3. Trope: “Half of the People” 4. Trope: “Thank You” VII. Mediation No. 2 VIII. Epistle: “The Word of the Lord” IX. Gospel-Sermon: “God Said” X. Credo 1. Credo in unum Deum 2. Trope: “Non Credo” 3. Trope: “Hurry” 4. Trope: “World without End” 5. Trope: “I Believe in God” XI. Meditation No. 3 (De profundis, part 1) XII. -

History of Lincolnshire Waterways

22 July 2005 The Sleaford Navigation Trust ….. … is a non-profit distributing company limited by guarantee, registered in England and Wales (No 3294818) … has a Registered Office at 10 Chelmer Close, North Hykeham, Lincoln, LN6 8TH … is registered as a Charity (No 1060234) … has a web page: www.sleafordnavigation.co.uk Aims & Objectives of SNT The Trust aims to stimulate public interest and appreciation of the history, structure and beauty of the waterway known as the Slea, or the Sleaford Navigation. It aims to restore, improve, maintain and conserve the waterway in order to make it fully navigable. Furthermore it means to restore associated buildings and structures and to promote the use of the Sleaford Navigation by all appropriate kinds of waterborne traffic. In addition it wishes to promote the use of towpaths and adjoining footpaths for recreational activities. Articles and opinions in this newsletter are those of the authors concerned and do not necessarily reflect SNT policy or the opinion of the Editor. Printed by ‘Westgate Print’ of Sleaford 01529 415050 2 Editorial Welcome Enjoy your reading and I look forward to meeting many of you at the AGM. Nav house at agm Letter from mick handford re tokem Update on token Lots of copy this month so some news carried over until next edition – tokens, nav house description www.river-witham.co.uk Martin Noble Canoeists enjoying a sunny trip along the River Slea below Cogglesford in May Photo supplied by Norman Osborne 3 Chairman’s Report for July 2005 Chris Hayes The first highlight to report is the official opening of Navigation House on June 2nd. -

Strong Start for Lady 'Gades

BAKERSFIELD COLLEGE Vol. 83 · No. 13 www.therip.com Wednesday, November 16, 2011 Strong start Teaching students for Lady 'Gades to be By Esteban Ramirez a 28-point and 13- rebound per Reporter formance against LATTC, gave her thoughts on how the team The Bakersfield College wom played. en's basketball team started off "We did really good against leaders its season with a win at College Allan Hancock and it was a good of the Sequoias and then two team effort, but I think we had By Keith Kaczmarek more victories at the Crossover a test against LATTC because Reporter Tournament at BC on Nov. 10- they were more athletic, and we 11. were tired from last night;' Mo- Becky Bell, the creator According to BC rales said. "That game and founder of Step Up!, a women's basketball showed us we college leadership program, coach Paula Dahl, Basketball's needed to work came to Bakersfield College to preview the program for there wasn't a Hot Start on our defense champion and and running BC's athletic program and usually four Nov.8 BC 73, Sequoias 64 our offense the Student Government As teams com- Nov. 10 BC 1 01 , Hancock 5 0 better." sociation. pete, but due Nov. 11 BC 76, LATIC 69 She added The program is focused on to a schedul- that everyone "people who step up;' a tag ing problem more feeds off each oth line for intervention in prob lems that affect students. teams showed up. er and when someone BC beat Allan Hancock 101- does something good, everyone "No matter the group, by 50 and Los Angeles Trade-Tech tries to do the same. -

Stockton House, Wiltshire : Heritage Statement – Documentary Sources

STOCKTON HOUSE, WILTSHIRE : HERITAGE STATEMENT – DOCUMENTARY SOURCES Version 0.5 – November 26, 2014 Fig 1 : J.C. Buckler, South-West View of Stockton House, Wiltshire. dated 1810 (courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, B1991.40.75) Andrew Foyle : Stockton House Heritage Statement, Version 0.5; November 26 2014 Page 1 CONTENTS: Preamble Pages 1-2 1. Change Control Log Page 3 2. Timeline for Stockton House Page 4 2. History and Development of the Building Page 17 3. Ownership and Owners’ Biographies Page 48 4. Appendices: Document Texts Page 57 A: Rev. Thomas Miles, History of the Parish of Stockton, B : Letter from W.H. Hartley, of Sutton, to John Hughes of Stockton, Friday Feb 26th, 1773 C : Auctions of Furniture from Stockton House, 1906 and 1920 D: A visitor’s comments on Stockton House in 1898. E : Kelly’s Directory of Wiltshire, 1898 F: Inquest Report on the Death of a Gardener, 1888 G: Transcripts of Four Articles on Stockton House in Country Life (1905 and 1984) H: Excerpt from The Gardeners’ Chronicle, February 23, 1895, p. 230. Abbrevations: WHC – Wiltshire History Centre, Chippenham (formerly Wiltshire Record Office) WILBR – Wiltshire Buildings Record at Wiltshire History Centre Introduction This paper sets out the documentary sources for the architectural development, phasing and dating of Stockton House. It was prepared by Andrew Foyle to inform the conservation and repair work to be carried out by Donald Insall Associates. Andrew Foyle : Stockton House Heritage Statement, Version 0.5; November 26 2014 Page 2 CHANGE CONTROL LOG Version 0.0 issued April 22 2014 Version 0.1 issued April 28 2014 Minor typographical changes.