A Corpus-Assisted Study of British Newspaper Discourse on the European Union and a Potential Membership Referendum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ideology and Social Attitudes: a Review of European and British Attitudes to European Integration Jeremiah J

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Ideology and Social Attitudes: A Review of European and British Attitudes to European Integration Jeremiah J. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY THE COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES IDEOLOGY AND SOCIAL ATTITUDES: A REVIEW OF EUROPEAN AND BRITISH ATTITUDES TO EUROPEAN INTEGRATION By JEREMIAH J. FISHER A Thesis submitted to the Department of International Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2005 The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Jeremiah J. Fisher defended on April 1, 2005. _____________________ Dale L. Smith Professor Directing Thesis _____________________ Burton M. Atkins Committee Member _____________________ Patrick M. O’Sullivan Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii In memory of my grandfather, Joseph Paul Blanchard, Whose gentle kindness I hope to always emulate. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the Florida State University, and especially the College of Social Sciences and Department of International Affairs, for providing fellowship assistance that has made this thesis and my graduate studies possible. I am especially thankful to my thesis director, Dale Smith, as well as my defense committee members, Burton Atkins and Patrick O’Sullivan, for agreeing to contribute time and ideas critical to completing the thesis process. While writing a thesis can often be a daunting task, the process has been eased by having positive feedback available to me. -

Postmodern Mentality in the Wasp Factory

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION Department of English Language and Literature Postmodern Mentality in The Wasp Factory Diploma thesis Brno 2012 Supervisor: Author: Mgr. Hana Waisserová, Ph.D. Mgr. Radek Holcepl 1 DECLARATION I declare that I worked on my diploma thesis independently and that I used only the sources listed in the bibliography. In České Budějovice August 2012 Mgr. Radek Holcepl .......................................................... 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisor Mgr. Hana Waisserová, Ph.D. for her kind guidance, patience and valuable comments and also to my wife for her support and understanding. 3 Bibliografický záznam Holcepl, Radek. Postmodern Mentality in The Wasp Factory. Brno: Masarykova univerzita, Fakulta pedagogická, Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury, 2012. XXX s. Vedoucí bakalářské práce - Mgr. Hana Waisserová, Ph.D. Anotace Diplomová práce je zaměřena na zkoumání širších kulturních souvislostí postmoderní mentality v díle Iana Bankse The Wasp Factory. Rozbor je věnován vztahu formy a obsahu díla z pohledu sociologie vědění a hlubinné psychologie. Význačné symboly jsou vykládány na základě analogií s díly antické mytologie i moderní filosofie. Součástí rozboru je i reflexe vztahu literatury, náboženství a technologie v postmoderní éře. Klíčová slova Postmoderna, psychopatologie, literatura a technologie, literatura a náboženství, narativní postupy a ideologie 4 Bibliography Holcepl, Radek. Postmodern Mentality in The Wasp Factory. Brno: Masaryk University, Faculty of Education, Department of English Language and Literature, 2012. XXX pages. The supervisor of the Bachelor Thesis – Mgr. Hana Waisserová, Ph.D. Annotation The Diploma Thesis is focused on the enquiry into broader cultural contexts of postmodern mentality in The Wasp Factory by Iain Banks. -

Book Review : Bob Crow : Socialist, Leader, Fighter : a Political Biography Darlington, RR

Book review : Bob Crow : Socialist, Leader, Fighter : a political biography Darlington, RR http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bjir.12270 Title Book review : Bob Crow : Socialist, Leader, Fighter : a political biography Authors Darlington, RR Type Article URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/43720/ Published Date 2017 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Bob Crow: Socialist, Leader, Fighter: A Political Biography. Gregor Gall. Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2017., ISBN: 978-1526100290, Price £20, hardback. During his term of office as general secretary of the National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers (RMT) during 2002-2014 until his early death at the age of 52, Bob Crow became one of the most widely known British union leaders of his generation. His stress on the virtues of militant resistance towards employers and government contributed to RMT members on the railways and London Underground organising (on a proportionate basis) probably more ballots for industrial action, securing more successful ‘yes’ votes, and taking strike action more often than any other union. In the process, Crow became the bête noire of the tabloid media, with the Evening Standard claiming he was ‘The Most Hated Man in London’. -

Making a Hasty Brexit? Ministerial Turnover and Its Implications

Making a Hasty Brexit? Ministerial Turnover and Its Implications Jessica R. Adolino, Ph. D. Professor of Political Science James Madison University Draft prepared for presentation at the European Studies Association Annual Meeting May 9-12, 2019, Denver, Colorado Please do not cite or distribute without author’s permission. By almost any measure, since the immediate aftermath of the June 16, 2016 Brexit referendum, the British government has been in a state of chaos. The turmoil began with then- Prime Minister David Cameron’s resignation on June 17 and succession by Theresa May within days of the vote. Subsequently, May’s decision to call a snap election in 2017 and the resulting loss of the Conservatives’ parliamentary majority cast doubt on her leadership and further stirred up dissension in her party’s ranks. Perhaps more telling, and the subject of this paper, is the unprecedented number of ministers1—from both senior and junior ranks—that quit the May government over Brexit-related policy disagreements2. Between June 12, 2017 and April 3, 2019, the government witnessed 45 resignations, with high-profile secretaries of state and departmental ministers stepping down to return to the backbenches. Of these, 34 members of her government, including 9 serving in the Cabinet, departed over issues with some aspect of Brexit, ranging from dissatisfaction with the Prime Minister’s Withdrawal Agreement, to disagreements about the proper role of Parliament, to questions about the legitimacy of the entire Brexit process. All told, Theresa May lost more ministers, and at a more rapid pace, than any other prime minister in modern times. -

BALLIOL COLLEGE ANNUAL RECORD 2019 1 ANNUAL RECORD 2019 Balliol College Oxford OX1 3BJ Telephone: 01865 277777 Website

2019 BALLIOL COLLEGE ANNUAL RECORD 2019 1 ANNUAL RECORD 2019 Balliol College Oxford OX1 3BJ Telephone: 01865 277777 Website: www.balliol.ox.ac.uk Editor: Anne Askwith (Publications and Web Officer) Printer: Ciconi Ltd FRONT COVER The JCR after refurbishment, 2019. Photograph by Stuart Bebb. Editorial note This year’s edition of the Annual Record sees some changes, as we continue to heed and act on the views expressed in the alumni survey 2017, review how best this publication can record what goes on at Balliol during the academic year, and endeavour to use resources wisely. For the first time theAnnual Record has been printed on 100% recycled paper. We are distributing it to more people via email (notifiying them that it is available online) and we have printed fewer copies than we did previously. To change your preference about whether you would like to receive a print copy of the Record or to be notified when it is available to read online (or if you would like to change how Balliol communicates with you or how you receive any of our publications), please contact the Development Office at the address opposite or manage your preferences online at www.alumniweb.ox.ac.uk/balliol. ‘News and Notes’ from Old Members (formerly in the Annual Record) is now published in Floreat Domus. We welcome submissions for the next edition, including news of births and marriages, and photographs: please send these by email to [email protected]. Deaths will continue to be listed in the Annual Record; please send details to the Development Office at the address opposite or by email to [email protected]. -

Party Parliamentary Group on Ending Homelessness

All Party Parliamentary Group on Ending Homelessness Emergency COVID-19 measures – Officers Meeting Minutes 13 July 2020, 10-11.30am, Zoom Attendees: Apologies: Neil Coyle MP, APPG Co-Chair Jason McCartney MP Bob Blackman MP, APPG Co-Chair Steve McCabe MP Lord Shipley Julie Marson MP Ben Everitt MP Stephen Timms MP Sally-Ann Hart MP Rosie Duffield MP Baroness Healy of Primrose Hill Debbie Abrahams MP Lord Holmes of Richmond Andrew Selous MP Lord Young of Cookham Kevin Hollinrake MP Feryal Clark MP Nickie Aiken MP Richard Graham MP Parliamentary Assistants: Layla Moran MP Graeme Smith, Office of Neil Coyle MP Damian Hinds MP James Sweeney, Office of Matt Western MP Tommy Sheppard MP Gail Harris, Office of Shaun Bailey MP Peter Dowd MP Harriette Drew, Office of Barry Sheerman MP Steve Baker MP Tom Leach, Office of Kate Osborne MP Tonia Antoniazzi MP Hannah Cawley, Office of Paul Blomfield MP Freddie Evans, Office of Geraint Davies MP Greg Oxley, Office of Eddie Hughes MP Sarah Doyle, Office of Kim Johnson MP Secretariat: Panellists: Emily Batchelor, Secretariat to APPG Matt Downie, Crisis Other: Liz Davies, Garden Court Chambers Jasmine Basran, Crisis Adrian Berry, Garden Court Chambers Ruth Jacob, Crisis Hannah Gousy, Crisis Cllr Kieron William, Southwark Council Disha Bhatt, Crisis Cabinet Member for Housing Management Saskia Neibig, Crisis and Modernisation Hannah Slater, Crisis Neil Munslow, Newcastle City Council Robyn Casey, Policy and Public Affairs Alison Butler, Croydon Council Manager at St. Mungo’s Chris Coffey, Porchlight Elisabeth Garratt, University of Sheffield Tim Sigsworth, AKT Jo Bhandal, AKT Anna Yassin, Glass Door Paul Anders, Public Health England Marike Van Harskamp, New Horizon Youth Centre Burcu Borysik, Revolving Doors Agency Kady Murphy, Just for Kids Law Emma Cookson, St. -

Brexit: Initial Reflections

Brexit: initial reflections ANAND MENON AND JOHN-PAUL SALTER* At around four-thirty on the morning of 24 June 2016, the media began to announce that the British people had voted to leave the European Union. As the final results came in, it emerged that the pro-Brexit campaign had garnered 51.9 per cent of the votes cast and prevailed by a margin of 1,269,501 votes. For the first time in its history, a member state had voted to quit the EU. The outcome of the referendum reflected the confluence of several long- term and more contingent factors. In part, it represented the culmination of a longstanding tension in British politics between, on the one hand, London’s relative effectiveness in shaping European integration to match its own prefer- ences and, on the other, political diffidence when it came to trumpeting such success. This paradox, in turn, resulted from longstanding intraparty divisions over Britain’s relationship with the EU, which have hamstrung such attempts as there have been to make a positive case for British EU membership. The media found it more worthwhile to pour a stream of anti-EU invective into the resulting vacuum rather than critically engage with the issue, let alone highlight the benefits of membership. Consequently, public opinion remained lukewarm at best, treated to a diet of more or less combative and Eurosceptic political rhetoric, much of which disguised a far different reality. The result was also a consequence of the referendum campaign itself. The strategy pursued by Prime Minister David Cameron—of adopting a critical stance towards the EU, promising a referendum, and ultimately campaigning for continued membership—failed. -

British Academy Review • 17

British Academy Review • 17 A MEDIEVAL MÊLÉE BRITISH ACADEMY British Academy Review Issue 17 March 2011 THE BRITISH ACADEMY 10–11 Carlton House Terrace, London SW1Y 5AH Telephone: 020 7969 5200 Fax: 020 7969 5300 Web site: www.britac.ac.uk © The British Academy 2011 The British Academy Review contains articles illustrating the wide range of scholarship which the British Academy promotes in its role as the UKs national academy for the humanities and social sciences. Views of named writers are the views exclusively of those writers; publication does not constitute endorsement by the British Academy. Suggestions for articles by current and former British Academy grant- and post-holders, as well as by Fellows of the British Academy, are very welcome. Suggestions may be sent to the Editor, James Rivington, at [email protected] Page make-up by Don Friston Printed in Great Britain on recycled paper by Henry Ling Limited at the Dorset Press Dorchester, Dorset Cover image: from the Jami al-Tawarikh manuscript, Edinburgh University Library iii Contents The coalition starts its white-knuckle ride 1 Martin Kettle The recession and stress at work 4 Professor Tarani Chandola Britain, Germany and Social Europe, 1973-2020 5 Sir Tony Atkinson FBA Social mobility: drivers and policy responses revisited 8 Professor Anthony Heath FBA and Dr Anna Zimdars Conflict resolution and reconciliation: An Irish perspective 11 Dáithí O’Ceallaigh British Academy President’s Medal 13 Medieval scenes Personifications of Old Age in medieval poetry: Charles d’Orléans 15 Professor Ad Putter The medieval Welsh poetry associated with Owain Glyndwˆr 18 Professor Gruffydd Aled Williams Forging the Anglo-Saxon past: Beverley Minster in the 14th century 23 Dr David Woodman The acts of medieval English bishops, illustrated 25 Dr Martin Brett Propaganda in the Mongol ‘World History’ 29 Professor Robert Hillenbrand FBA Portable Christianity: Relics in the Medieval West (c.700-1200) 39 Professor Julia Smith The stone sculptures of Anglo-Saxon England 41 Professor Rosemary Cramp FBA and Professor Richard N. -

25 Haigron Ac

Cercles 25 (2012) !"#$#%&'()#*)#!"#&)+&,()-.".'/-#+/!'.'01)#2# #(34+./4)(5#*'"6-/(.'%(#).#&)4)*)(#+&/+/()(# # # # *"7'*#8"'6&/-# !"#$%&'#()*+%*,-%"# # ! "#! $%&'(#)*#*! +$+,-*#*! )$./#(*.0+.(#*! #0! 1%)($+,.*0.2)#*! 3%$/#(4#$0! 5%)(! 6.+4$%*0.2)#(! )$#! 7!3(.*#! 6#! ,+! (#5(8*#$0+0.%$! 5%,.0.2)#!9! 6+$*! ,#*! 68&%3(+0.#*!%33.6#$0+,#*:!;#!<%-+)&#=>$.!$?#*0!5+*!85+(4$8!5+(!3#!3%$*0+0:! @#3.!*?#A5(.&#B!#$0(#!+)0(#*B!5+(!)$#!*)*5.3.%$!4(+$6.**+$0#!C!,?84+(6!6#!,+! 3,+**#! 5%,.0.2)#! D4%)/#($#&#$0B! 5+(,#&#$0B! 5+(0.*EB! #A5(.&8#! 6+$*! ,#*! *%$6+4#*! 6?%5.$.%$B! 5+(! )$#! F+)**#! 6#! ,?+'*0#$0.%$! %)! 5+(! )$! /%0#! 5,)*! G,)30)+$0! #0! 5,)*! 83,+08:! ;#*! 3+)*#*! *)55%*8#*! *%$0! 6.GG)*#*B! &+.*! *#! 3(.*0+,,.*#$0!+)0%)(!6)!*#$0.&#$0!2)#!,#*!5+(0.*!5%,.0.2)#*B!#$!48$8(+,B!#0!,#*! 4%)/#($#&#$0*B!#$!5+(0.3),.#(B!$#!(#*5#30#$0!5+*!,+!/%,%$08!6#!,?8,#30%(+0!#0! 2)#!,#)(!+30.%$!$#!*#(0!5+*!#$!5(.%(.08!3#)A!2)?.,*!*%$0!3#$*8*!(#5(8*#$0#(:!@#! 2).! G+.0! 7!3(.*#!9! #*0! 6%$3! ,+! (#&.*#! #$! 3+)*#! 5+(! ,#*! 3.0%-#$*B! 6+$*! ,#*! 68&%3(+0.#*!6.0#*!(#5(8*#$0+0./#*B!6#!,+!,84.0.&.08!6#!,#)(*!(#5(8*#$0+$0*!D,#*! 8,)*E!C!,#*!(#5(8*#$0#(!D3?#*0=C=6.(#!C!5(#$6(#!6#*!683.*.%$*!#$!,#)(!$%&E:! "?)$#!&+$.H(#!48$8(+,#B!,+!$%0.%$!6#!7!3(.*#!9!*)55%*#!)$#!()50)(#!5+(! (+55%(0! C! )$! %(6(#! 80+',.! %)! .68+,:! "+$*! ,#! 6.*3%)(*! 5%,.0.2)#B! #,,#! 3%((#*5%$6! C! )$! 68(H4,#&#$0! +)2)#,! .,! G+)0! +55%(0#(! )$#! 7!*%,)0.%$!9! D,#! 5,)*! *%)/#$0! 6+$*! ,?)(4#$3#E! #0! *#*! 3+)*#*! *%$0! ,#! 5,)*! *%)/#$0! 5(8*#$08#*! 3%&&#! #A%4H$#*:! @#3.! *#! /8(.G.#! 5+(0.3),.H(#&#$0! -

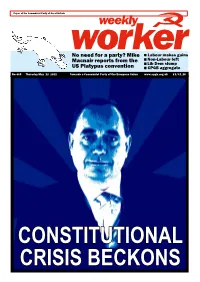

Mike Macnair

Paper of the Communist Party of Great Britain weekly No need for a party? Mike n Labour makes gains workern Non-Labour left Macnair reports from the n Lib Dem slump US Platypus convention n CPGB aggregate No 865 Thursday May 12 2011 Towards a Communist Party of the European Union www.cpgb.org.uk £1/€1.10 CONSTITUTIONAL CRISIS BECKONS 8 May 12 2011 865 US LEFT No need for party? The US Platypus grouping does not have a political line because there is ‘no possibility of revolutionary action’. Mike Macnair reports on its convention attended the third annual Platypus about madness and the penitentiary, as International Convention in Chi- well as about the history of sexuality, Icago over the weekend April 29- have been falsified by historians. May 1. The Platypus Affiliated So- And, though he identified Foucault’s ciety is a, mainly student, left group tendency to marginalise class politics, of an odd sort (as will appear further he saw this as merely a product of the below). Its basic slogan is: ‘The left defeat of the left, rather than as an is dead; long live the left’. Starting active intervention in favour of popular very small, it has recently expanded frontism. Hence he missed the extent rapidly on US campuses and added to which the Anglo-American left chapters in Toronto and Frankfurt. academic and gay/lesbian movement Something over 50 people attended reception of Foucault was closely tied the convention. to the defence of extreme forms of The fact of Platypus’s rapid growth popular frontism by authors directly on the US campuses, though still as or indirectly linked to Marxism yet to a fairly small size, tells us that Today, for whom it was an instrument in some way it occupies a gap on the against the ‘class-reductionist’ ideas US left, and also tells us something of Trotskyists. -

No. 207, Summer, 2009

No 207 SUMMER 2009 40p Newspaper of the Spartacist League Forge a multiethnic revolutionary workers party! if" publish helow an edited alld Depression wasn't Roosevelt's New .~~ -'--- __ .1. ~_ •• ~.~. ___ ............. ___ •• ' f (}n~'&8'&W UJ (P. MONI',_ Deal, but World War 11. It was when . gil'cll h)' cOlJlrade Julia Effie,}' at a the imperialist governments In Spartacist League public meeting ;n Britain and the US mobilised their London on 4 April. economies for WWlI that they fully The ongoing world capitalist reces adopted Keynes's programme of sion is having a tremendous impact on deficit spending for "public works" the British economy and inflicting -- battleships, bombers, tanks and severe hardship on working people. finally atomic hombs. Thc lahour Across Britain the rate of home repos movement must oppose protec sessions is rising while the nllmber of tionism and fight fur international job losses is cnonnolls. The working~class solidarity. crisis has demonstrated quill..' Production itself is socialised openly the hmlkruptcy and irra~ Unions must defend immigrant workers! and international in scope tionality of the capitalist sys~ and the international working tem and what the leaders of all class must he mohilised capitalist countries agree on is Down with chauvinist construction strikes! across national and other that working people will be divisions. made to pay for it. It also confinTIs the Marxist understanding that ultimately Reactionary strikes tht..:rc is no answer to the boom-and-bust Since January a series of reactionary cycles of capitalism short of proletarian and virulently chauvinist strikes and socialist revolution that takes power out protests havc taken place on building of the hands of the capitalist ruling class sites at Britain's power stations and oil and replaces it with a planned, refineries. -

A Letter to Trade Union National Executive Committee Members

Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition, 17 Colebert House, Colebert Avenue, London, E1 4JP A letter to trade union national executive committee members Dear comrade, I am writing to invite you to consider joining the national steering committee of the recently relaunched Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition (TUSC). As you may recall TUSC was set-up in 2010, co-founded amongst others by the late Bob Crow, with trade unionists at its core (a brief history is available at http://www.tusc.org.uk/txt/429.pdf). Our founding aim was to help in the process of re-establishing a political voice for the working class given, at that point, the transformation of the Labour Party into Tony Blair’s New Labour and its role in implementing the austerity unleashed by the 2007-08 financial crash. As our name says we are a coalition and all of the component elements of TUSC have played their part alongside other campaigners in the struggles of the last decade against attacks on jobs, services and conditions – in the workplace, in our communities, and in the trade unions. But we have also been prepared to stand in elections where necessary, believing that to leave politicians who are carrying out cuts unchallenged at the ballot box, is to voluntarily give up a weapon that could be used in the anti-austerity struggle. This is particularly so in local government, in which councillors are the direct employers and providers of local services. In this situation to positively decide not to have an anti-austerity candidate standing when cuts are being made would be to give an effective vote of confidence to the local authority’s policies.