Review of the Medically Supervised Injecting Room Medically Supervised Injecting Room Review Panel, June 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legislative Assembly of Victoria

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF VICTORIA VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS Nos 54, 55 and 56 No 54 — Tuesday 18 February 2020 1 The House met according to the adjournment — The Speaker took the Chair, read the Prayer and made an Acknowledgement of Country. 2 QUESTION TIME — (Under Sessional Order 9). 3 LOCAL GOVERNMENT (CASEY CITY COUNCIL) BILL 2020 — Ms Kairouz introduced ‘A Bill for an Act to dismiss the Casey City Council and to provide for a general election for that Council and for other purposes’; and the Bill was read a first time. In accordance with SO 61(3)(b), the House proceeded immediately to the second reading. Ms Kairouz tabled a statement of compatibility in accordance with the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006. Motion made and question proposed — That this Bill be now read a second time (Ms Kairouz). The second reading speech was incorporated into Hansard. Motion made and question — That the debate be now adjourned (Mr Smith, Kew) — put and agreed to. Ordered — That the debate be adjourned until later this day. 4 NATIONAL ELECTRICITY (VICTORIA) AMENDMENT BILL 2020 — Ms D’Ambrosio introduced ‘A Bill for an Act to amend the National Electricity (Victoria) Act 2005 and the Electricity Industry Act 2000 and for other purposes’; and the Bill was read a first time and ordered to be read a second time tomorrow. 5 DOCUMENTS CITY OF CASEY MUNICIPAL MONITOR REPORT FEBRUARY 2020 — Tabled by leave (Ms Kairouz). Ordered to be published. 288 Legislative Assembly of Victoria SCRUTINY OF ACTS AND REGULATIONS COMMITTEE — Ms Connolly tabled the Alert Digest No 2 of 2020 from the Scrutiny of Acts and Regulations Committee on the: Children, Youth and Families Amendment (Out of Home Care Age) Bill 2020 Crimes Amendment (Manslaughter and Related Offences) Bill 2020 Forests Legislation Amendment (Compliance and Enforcement) Bill 2019 Project Development and Construction Management Amendment Bill 2020 Transport Legislation Amendment Act 2019 (House Amendment) SR No 93 — Road Safety (Traffic Management) Regulations 2019 together with appendices. -

Legislative Assembly of Victoria

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF VICTORIA VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS Nos 47, 48 and 49 No 47 — Tuesday 26 November 2019 1 The House met according to the adjournment — The Speaker took the Chair, read the Prayer and made an Acknowledgement of Country. 2 QUESTION TIME — (Under Sessional Order 9). 3 GREAT OCEAN ROAD AND ENVIRONS PROTECTION BILL 2019 — Ms D’Ambrosio obtained leave to bring in ‘A Bill for an Act to recognise the importance of the landscapes and seascapes along the Great Ocean Road to the economic prosperity and liveability of Victoria and as one living and integrated natural entity for the purposes of protecting the region, to establish a Great Ocean Road Coast and Parks Authority to which various land management responsibilities are to be transferred and to make related and consequential amendments to other Acts and for other purposes’; and, after debate, the Bill was read a first time and ordered to be read a second time tomorrow. 4 ROAD SAFETY AND OTHER LEGISLATION AMENDMENT BILL 2019 — Ms Neville obtained leave to bring in ‘A Bill for an Act to amend the Road Safety Act 1986 to provide for immediate licence or permit suspensions in certain cases and to make consequential and related amendments to that Act and to make minor amendments to the Sentencing Act 1991 and for other purposes’; and, after debate, the Bill was read a first time and ordered to be read a second time tomorrow. 5 GENDER EQUALITY BILL 2019 — Ms Williams obtained leave to bring in ‘A Bill for an Act to require the public sector, Councils and universities to promote gender equality, to take positive action towards achieving gender equality, to establish the Public Sector Gender Equality Commissioner and for other purposes’; and, after debate, the Bill was read a first time and ordered to be read a second time tomorrow. -

CBD News Editions 38 – December 2017 / January 2018

FOR THE MONTHS OF DECEMBER 2017 & JANUARY 2018 ISSUE 38 WWW.CBDNEWS.COM.AU 㿱 25 亥 FREE ON THE OTHER SIDE YEAR OF THE DOG IS COMING CAPITOL THEATRE APPEAL FLINDERS ST REVEALED - page 2 - - page 5 - - page 6 - - page 11 - City Square cash deal By Shane Scanlan said. “But, one way or another, we’ll have the cash to buy back the public space.” Fears have been allayed that Cr Wood said the council decided the sale and repurchase of the square was the City of Melbourne may not the cleanest way to deal with the matter have the cash to buy back the because it was not known what condition or remaining parts of the square would City Square when the Metro be available when the rail project was Tunnel project is complete. completed. “We don’t know at this stage exactly how Th e council earlier this year sold the square much of the square will be used for Metro to the State Government for around $67 Tunnel,” Cr Wood said. million and it was feared the money would “We know there will be less public open be spent on the Queen Victoria Market space, but not the absolute fi nal design. (QVM) renewal project. However, the City of Melbourne is working In April 2014, the council resolved to with Metro throughout the entire process establish a fund to pay for the QVM. to ensure the fi nal design is mutually benefi cial for everyone, most importantly It also resolved: “Commencing from 1 the residents, workers and visitors to the July 2014, all profi t proceeds from the sale city.” of any other surplus or redundant City of “Th e cleanest way is to sell the lot and Melbourne land holdings will be deposited negotiate the repurchase when the time into the fund.” comes at the mutually agreed value, But Deputy Lord Mayor and fi nance chair providing it is in line with the approved Arron Wood says funds received from masterplan.” the sale of the City Square will be held in “It was impossible to negotiate a binding trust to an agreed amount currently under agreement when there was so many negotiation with the Valuer-General. -

Federal & State Mp Phone Numbers

FEDERAL & STATE MP PHONE NUMBERS Contact your federal and state members of parliament and ask them if they are committed to 2 years of preschool education for every child. Federal electorate MP’s name Political party Phone Federal electorate MP’s name Political party Phone Aston Alan Tudge Liberal (03) 9887 3890 Hotham Clare O’Neil Labor (03) 9545 6211 Ballarat Catherine King Labor (03) 5338 8123 Indi Catherine McGowan Independent (03) 5721 7077 Batman Ged Kearney Labor (03) 9416 8690 Isaacs Mark Dreyfus Labor (03) 9580 4651 Bendigo Lisa Chesters Labor (03) 5443 9055 Jagajaga Jennifer Macklin Labor (03) 9459 1411 Bruce Julian Hill Labor (03) 9547 1444 Kooyong Joshua Frydenberg Liberal (03) 9882 3677 Calwell Maria Vamvakinou Labor (03) 9367 5216 La Trobe Jason Wood Liberal (03) 9768 9164 Casey Anthony Smith Liberal (03) 9727 0799 Lalor Joanne Ryan Labor (03) 9742 5800 Chisholm Julia Banks Liberal (03) 9808 3188 Mallee Andrew Broad National 1300 131 620 Corangamite Sarah Henderson Liberal (03) 5243 1444 Maribyrnong William Shorten Labor (03) 9326 1300 Corio Richard Marles Labor (03) 5221 3033 McEwen Robert Mitchell Labor (03) 9333 0440 Deakin Michael Sukkar Liberal (03) 9874 1711 McMillan Russell Broadbent Liberal (03) 5623 2064 Dunkley Christopher Crewther Liberal (03) 9781 2333 Melbourne Adam Bandt Greens (03) 9417 0759 Flinders Gregory Hunt Liberal (03) 5979 3188 Melbourne Ports Michael Danby Labor (03) 9534 8126 Gellibrand Timothy Watts Labor (03) 9687 7661 Menzies Kevin Andrews Liberal (03) 9848 9900 Gippsland Darren Chester National -

Parliament of Victoria

Current Members - 23rd January 2019 Member's Name Contact Information Portfolios Hon The Hon. Daniel Michael 517A Princes Highway, Noble Park, VIC, 3174 Premier Andrews MP (03) 9548 5644 Leader of the Labor Party Member for Mulgrave [email protected] Hon The Hon. James Anthony 1635 Burwood Hwy, Belgrave, VIC, 3160 Minister for Education Merlino MP (03) 9754 5401 Deputy Premier Member for Monbulk [email protected] Deputy Leader of the Labor Party Hon The Hon. Michael Anthony 313-315 Waverley Road, Malvern East, VIC, 3145 Shadow Treasurer O'Brien MP (03) 9576 1850 Shadow Minister for Small Business Member for Malvern [email protected] Leader of the Opposition Leader of the Liberal Party Hon The Hon. Peter Lindsay Walsh 496 High Street, Echuca, VIC, 3564 Shadow Minister for Agriculture MP (03) 5482 2039 Shadow Minister for Regional Victoria and Member for Murray Plains [email protected] Decentralisation Shadow Minister for Aboriginal Affairs Leader of The Nationals Deputy Leader of the Opposition Hon The Hon. Colin William Brooks PO Box 79, Bundoora, VIC Speaker of the Legislative Assembly MP Suite 1, 1320 Plenty Road, Bundoora, VIC, 3083 Member for Bundoora (03) 9467 5657 [email protected] Member's Name Contact Information Portfolios Mr Shaun Leo Leane MLC PO Box 4307, Knox City Centre, VIC President of the Legislative Council Member for Eastern Metropolitan Suite 3, Level 2, 420 Burwood Highway, Wantirna, VIC, 3152 (03) 9887 0255 [email protected] Ms Juliana Marie Addison MP Ground Floor, 17 Lydiard Street North, Ballarat Central, VIC, 3350 Member for Wendouree (03) 5331 1003 [email protected] Hon The Hon. -

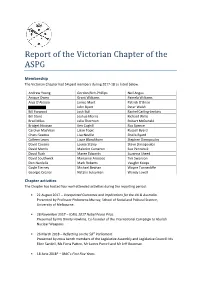

Report of the Victorian Chapter of the ASPG

Report of the Victorian Chapter of the ASPG Membership The Victorian Chapter had 54 paid members during 2017-18 as listed below. Andrew Young Gordon Rich-Phillips Neil Angus Anique Owen Grant Williams Pamela Williams Anja D’Alessio Janice Munt Patrick O’Brien John Byatt Peter Walsh Bill Forwood Josh Bull Rachel Carling-Jenkins Bill Stent Joshua Morris Richard Willis Brad Miles Julia Thornton Robert McDonald Bridget Noonan Ken Coghill Ros Spence Carolyn MacVean Lilian Topic Russell Byard Charu Saxena Lisa Neville Sheila Byard Colleen Lewis Lizzie Blandthorn Stephen Dimopoulos David Cousins Louise Staley Steve Dimopoulos David Morris Malcolm Cameron Sue Pennicuik David Rush Maree Edwards Suzanna Sheed David Southwick Marianne Aroozoo Tim Swanson Don Nardella Mark Roberts Vaughn Koops Gayle Tierney Michael Beahan Wayne Tunnecliffe Georgie Crozier Natalie Suleyman Wendy Lovell Chapter activities The Chapter has hosted four well-attended activities during the reporting period: • 22 August 2017 – Unexpected Outcomes and Implications for the UK & Australia. Presented by Professor Philomena Murray, School of Social and Political Science, University of Melbourne. • 28 November 2017 – ICAN, 2017 Nobel Peace Prize. Presented by Ms Dimity Hawkins, Co-founder of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons. • 26 March 2018 – Reflecting on the 58th Parliament. Presented by cross bench members of the Legislative Assembly and Legislative Council: Ms Ellen Sandell, Ms Fiona Patten, Mr James Purcell and Mr Jeff Bourman. • 18 June 2018* – IBAC’s First Five Years. Presented by Mr Alistair Maclean, Chief Executive Officer, Independent Broad-based Anti- corruption Commission. *This seminar was postponed to 23 July 2018. Corporate membership votes at AGM • ASPG Victoria Chapter is unaware of formal requests by the parent body for corporate membership, including any amounts paid. -

ISSUE 220: the Budgety Edition (24 March to 8 May 2017)

Issue 220 24 March to 8 May 2017 Letter from MelbourneA monthly public affairs bulletin, a simple précis, distilling and interpreting public policy and government decisions, which affect business opportunities in Victoria and Australia. Now into our twenty-fourth year. The Budgety Edition In This Issue: ʇ Heywood Timber ʇ Gas, and Fracking ʇ Desalish ʇ Infrastructure Pipeline (What’s that exactly?) ʇ The CFA Fight ʇ Energetic Victoria, or not.. ʇ Al Gore ʇ Our Police philosophy ʇ Hazelwood ʇ Bin Tax Letter From Melbourne // Issue 220 Letter from Melbourne About Us Since 1994. A monthly public affairs newsletter distilling public policy and Affairs of State govern-ment decisions which effect business opportunities in Victoria, 43 Richmond Terrace Australia and beyond. 2,500,000 words available to search digitally. Richmond, Melbourne, 3121 Victoria, Australia Contents P 03 9654 1300 Editorial ....................................................3 Justice ...................................................... 8 [email protected] www.affairs.com.au Governance ..............................................3 Local Government .................................. 9 Letter From Melbourne is a monthly public affairs bulletin, a simple précis, distilling and What is fracking? (bbc.com) .................. 4 Education ............................................... 9 interpreting public policy and government decisions, which affect business oppor- Federal .................................................... 4 Melbourne ..............................................10 -

Research Paper

Parliamentary Library & Information Service Department of Parliamentary Services Parliament of Victoria Parliamentary Library & Information Service Department of Parliamentary Services Parliament of Victoria Research Paper Research Paper The 2014 Victorian State Election No. 1, June 2015 Bella Lesman Rachel Macreadie Dr Catriona Ross Paige Darby Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank their colleagues in the Research & Inquiries Service, Alice Jonas and Marianne Aroozoo for their checking of the statistical tables, proof-reading and suggestions and Debra Reeves for proof-reading. Thanks also to Paul Thornton-Smith and the Victorian Electoral Commission for permission to re-produce their election results maps, for two-party preferred results and swing data based on the redivision of electoral boundaries, and for their advice. Thanks also to Professor Brian Costar, Associate Professor Paul Strangio, Nathaniel Reader, research officer from the Parliament of Victoria’s Electoral Matters Committee, and Bridget Noonan, Deputy Clerk of the Victorian Legislative Assembly for reading a draft of this paper and for their suggestions and comments. ISSN 2204-4752 (Print) 2204-4760 (Online) © 2015 Parliamentary Library & Information Service, Parliament of Victoria Research Papers produced by the Parliamentary Library & Information Service, Department of Parliamentary Services, Parliament of Victoria are released under a Creative Commons 3.0 Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs licence. By using this Creative Commons licence, you are free to share - to copy, distribute and transmit the work under the following conditions: . Attribution - You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). -

Membersdirectory.Pdf

The 59th Parliament of Victoria ADDISON, Ms Juliana Wendouree Australian Labor Party Legislative Assembly Parliamentary Service ADDISON, Ms Juliana Elected MLA for Wendouree November 2018. Committee Service Legislative Assembly Economy and Infrastructure Committee since March 2019. Localities with Electorate Localities: Alfredton, Ballarat Central, Ballarat North, Black Hill, Delacombe, Invermay, Invermay Park, Lake Gardens, Nerrina, Newington, Redan, Soldiers Hill and Wendouree. Parts of Bakery Hill, Ballarat East and Brown Hill., Election Area km2: 114 Electorate Office Address Ground Floor, 17 Lydiard Street North Ballarat Central VIC 3350 Telephone (03) 5331 1003 Email [email protected] Facebook www.facebook.com/JulianaAddisonMP Twitter https://twitter.com/juliana_addison Website www.JulianaAddison.com.au ALLAN, The Hon Jacinta Bendigo East Australian Labor Party Legislative Assembly Minister for Transport Infrastructure Minister for the Coordination of Transport: COVID-19 Minister for the Suburban Rail Loop Priority Precincts March 2020 - June 2020. Minister for the Parliamentary Service ALLAN, The Hon Jacinta Elected MLA for Bendigo East September 1999. Re-elected Coordination of Transport: COVID-19 since April 2020. November 2002, November 2006, November 2010, Minister for the Suburban Rail Loop since June 2020. November 2014, November 2018. ; Party Positions Parliamentary Party Position Delegate, Young Labor Conference 1993-95. Secretary, Leader of the House since December 2014. Manager of Bendigo South Branch 1994. Secretary 1995-97, Pres. 1997- Opposition Business since December 2010. 2000, Bendigo Federal Electorate Assembly. Committee Service Personal Dispute Resolution Committee since February 2019. Born Bendigo, Victoria, Australia.Married, two children. Legislative Assembly Privileges Committee since February Education and Qualifications 2019. Legislative Assembly Standing Orders Committee BA(Hons) 1995 (La Trobe). -

The Pokies Play You

THE POKIES PLAY YOU Revealed: Vic pokies losses highest in safest Labor seats Monday, November 12, 2018 As Victorian pokies gambling soars to record levels ahead of the November 24 state election, The Alliance for Gambling Reform today revealed a league ladder of losses by State seats showing the greatest harm is being caused in safe Labor seats. Premier Daniel Andrews, Racing Minister Martin Pakula and Gaming Minister Marlene Kairouz all hold safe seats which appear in the top 10 for losses, whilst Liberal leader Matthew Guy represents the only conservative seat appearing in the top 20. (See spreadsheet with rankings of all 88 seats.) The Alliance today also released an interactive map showing the 2017-18 pokies losses by lower house seats and upper house regions, including machine and venue numbers, plus both annualised and daily losses. Click on any of the 88 seats on the map and you will see where it ranks for losses in absolute terms and measured on a per capita basis. Excluding Crown ($450m in pokies losses in the seat of Albert Park), the central city seat of Melbourne suffered the greatest losses in 2017-18 with $84 million whilst the safe Liberal seat of Warrandyte was the lowest with its single venue generating losses of just $7.66 million. The 12 Victorian seats where pokies losses topped $50m in 2017-18 were: 1. Melbourne: (Greens, Ellen Sandell): $84 million 2. Preston: (Labor, Robin Scott): $64.1m 3. Footscray: (Labor, incoming Katie Hall): $63.7m 4. Oakleigh: (Labor, Steve Dimopoulos): $59.57m 5. Keysborough: (Labor, Racing Minister Martin Pakula): $59.2m 6. -

The 2018 Victorian State Election

The 2018 Victorian State Election Research Paper No. 2, June 2019 Bella Lesman, Alice Petrie, Debra Reeves, Caley Otter Holly Mclean, Marianne Aroozoo and Jon Breukel Research & Inquiries Unit Parliamentary Library & Information Service Department of Parliamentary Services Parliament of Victoria Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank their colleague in the Research & Inquiries Service, Meghan Bosanko for opinion poll graphs and the checking of the statistical tables. Thanks also to Paul Thornton-Smith and the Victorian Electoral Commission for permission to reproduce their election results maps and for their two-candidate preferred results. ISSN 2204-4752 (Print) 2204-4760 (Online) Research Paper: No. 2, June 2019. © 2019 Parliamentary Library & Information Service, Parliament of Victoria Research Papers produced by the Parliamentary Library & Information Service, Department of Parliamentary Services, Parliament of Victoria are released under a Creative Commons 3.0 Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs licence. By using this Creative Commons licence, you are free to share - to copy, distribute and transmit the work under the following conditions: . Attribution - You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non-Commercial - You may not use this work for commercial purposes without our permission. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work without our permission. The Creative Commons licence only applies to publications produced by the Library, Department of Parliamentary Services, Parliament of Victoria. All other material produced by the Parliament of Victoria is copyright. If you are unsure please contact us. -

Who Decides If We Die in Extreme Suffering?

Who are we Melbourne Parliamentarians Retirement Village Electorate Member Office Address Phone Residents of Victoria We are residents, family and friends of present and Albert Park Martin Foley 46 Rouse St, Port Melbourne 3207 9646 7173 past retirement village residents. Some of us work Altona Jill Hennessey Suite 603, Level 1, 2 Main St, Point Cook 9395 0221 Town Centre, Point Cook 3030 with villages. We are nearly all volunteers and Bayswater Heidi Victoria Suite 2, Mountain High Centre, 7 High St, 9729 1622 Bayswater 3153 personally contributing the funds for this brochure. Bentleigh Nick Staikos 723 Centre Rd, Bentleigh East 3165 9579 7222 Box Hill Robert Clark 24 Rutland Rd, Box Hill 3128 9898 6606 We support Andrew Denton’s Go Gentle Australia Brighton Louise Asher Ground Floor, 315 New St, Brighton 3186 9592 1900 Who decides if we die in Broadmeadows Frank McGuire Shop G42, Broadmeadows Shopping 9300 3851 and Stop Victorians Suffering who provide Centre, Broadmeadows 3047 Brunswick Jane Garrett Suite 1, 31 Nicholson St, 9384 1241 extreme suffering? us advice and guidance. Brunswick East 3057 Bulleen Matthew Guy Shop 30D, Bulleen Plaza, 101 Manningham Rd, 9850 7983 Bulleen 3105 Bundoora Colin Brooks Suite 1, 1320 Plenty Rd, Bundoora 3083 9467 5657 Politicians, if we Please help us to be heard Burwood Graham Watt 1342 Toorak Rd, Camberwell 3124 9809 1857 Carrum Sonya Kilkenny Ground Floor, 622 Nepean Hwy, Carrum 3197 9773 2727 Caulfield David Southwick Suite 1/193, Balaclava Rd, Caulfield North 3161 9527 3866 don’t speak now. – donate $5 Clarinda Hong Lim Level 1, 1312 Centre Rd, Clayton South 3169 9543 6081 Cranbourne Jude Perera 157A Sladen St, Cranbourne 3997 5996 2901 As we get closer to the vote the powerful (and Croydon David Hodgett 60 Main St, Croydon 3136 9725 3570 Dandenong Gabrielle Williams Retail 1, 8-10 Halpin Way, Dandenong 3175 9793 2000 Our voices wealthy) groups who don’t want change will Eltham Vicki Ward 718 Main Rd, Eltham 3095 9439 1500 Essendon Danny Pearson Suite 1, 28 Shuter St, Moonee Ponds 3039 9370 7777 .