Frame by Frame

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Disney Strike of 1941: from the Animators' Perspective Lisa Johnson Rhode Island College, Ljohnson [email protected]

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC Honors Projects Overview Honors Projects 2008 The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators' Perspective Lisa Johnson Rhode Island College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects Part of the Labor Relations Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Lisa, "The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators' Perspective" (2008). Honors Projects Overview. 17. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects/17 This Honors is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Projects at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects Overview by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators’ Perspective An Undergraduate Honors Project Presented By Lisa Johnson To The Department of History Approved: Project Advisor Date Chair, Department Honors Committee Date Department Chair Date The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators’ Perspective By Lisa Johnson An Honors Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in The Department of History The School of the Arts and Sciences Rhode Island College 2008 1 Table of Contents Introduction Page 3 I. The Strike Page 5 II. The Unheard Struggles for Control: Intellectual Property Rights, Screen Credit, Workplace Environment, and Differing Standards of Excellence Page 17 III. The Historiography Page 42 Afterword Page 56 Bibliography Page 62 2 Introduction On May 28 th , 1941, seventeen artists were escorted out of the Walt Disney Studios in Burbank, California. -

Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Queens College 2017 Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios Kevin L. Ferguson CUNY Queens College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/qc_pubs/205 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios Abstract There are a number of fruitful digital humanities approaches to cinema and media studies, but most of them only pursue traditional forms of scholarship by extracting a single variable from the audiovisual text that is already legible to scholars. Instead, cinema and media studies should pursue a mostly-ignored “digital-surrealism” that uses computer-based methods to transform film texts in radical ways not previously possible. This article describes one such method using the z-projection function of the scientific image analysis software ImageJ to sum film frames in order to create new composite images. Working with the fifty-four feature-length films from Walt Disney Animation Studios, I describe how this method allows for a unique understanding of a film corpus not otherwise available to cinema and media studies scholars. “Technique is the very being of all creation” — Roland Barthes “We dig up diamonds by the score, a thousand rubies, sometimes more, but we don't know what we dig them for” — The Seven Dwarfs There are quite a number of fruitful digital humanities approaches to cinema and media studies, which vary widely from aesthetic techniques of visualizing color and form in shots to data-driven metrics approaches analyzing editing patterns. -

A Totally Awesome Study of Animated Disney Films and the Development of American Values

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 2012 Almost there : a totally awesome study of animated Disney films and the development of American values Allyson Scott California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes Recommended Citation Scott, Allyson, "Almost there : a totally awesome study of animated Disney films and the development of American values" (2012). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 391. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes/391 This Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. Unless otherwise indicated, this project was conducted as practicum not subject to IRB review but conducted in keeping with applicable regulatory guidance for training purposes. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Social and Behavioral Sciences Department Senior Capstone California State University, Monterey Bay Almost There: A Totally Awesome Study of Animated Disney Films and the Development of American Values Dr. Rebecca Bales, Capstone Advisor Dr. Gerald Shenk, Capstone Instructor Allyson Scott Spring 2012 Acknowledgments This senior capstone has been a year of research, writing, and rewriting. I would first like to thank Dr. Gerald Shenk for agreeing that my topic could be more than an excuse to watch movies for homework. Dr. Rebecca Bales has been a source of guidance and reassurance since I declared myself an SBS major. Both have been instrumental to the completion of this project, and I truly appreciate their humor, support, and advice. -

The University of Chicago Looking at Cartoons

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LOOKING AT CARTOONS: THE ART, LABOR, AND TECHNOLOGY OF AMERICAN CEL ANIMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY HANNAH MAITLAND FRANK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 FOR MY FAMILY IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER Apparently he had examined them patiently picture by picture and imagined that they would be screened in the same way, failing at that time to grasp the principle of the cinematograph. —Flann O’Brien CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION LOOKING AT LABOR......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 ANIMATION AND MONTAGE; or, Photographic Records of Documents...................................................22 CHAPTER 2 A VIEW OF THE WORLD Toward a Photographic Theory of Cel Animation ...................................72 CHAPTER 3 PARS PRO TOTO Character Animation and the Work of the Anonymous Artist................121 CHAPTER 4 THE MULTIPLICATION OF TRACES Xerographic Reproduction and One Hundred and One Dalmatians.......174 -

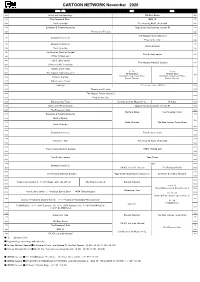

2020 November(2).Xlsx

CARTOON NETWORK November 2020 MON. -FRI. SAT. SUN. 4:00 Grizzy and the Lemmings We Bare Bears 4:00 4:30 The Powerpuff Girls BEN 10 4:30 5:00 Uncle Grandpa The Amazing World of Gumball 5:00 5:30 Sylvester & Tweety Mysteries Oggy & the Cockroaches (season 5) 5:30 6:00 Thomas and Friends 6:00 The Happos Family Season 2 6:30 6:30 Sergeant Keroro(J) Pingu in the City 6:40 7:00 Sergeant Keroro(J) 7:00 Uncle Grandpa 7:30 Uncle Grandpa 7:30 8:00 The Amazing World of Gumball Tom & Jerry series 8:00 8:30 TEEN TiTANS GO! 9:00 Tom & Jerry series The Amazing World of Gumball 9:00 9:30 Grizzy and the Lemmings 10:00 Thomas and Friends 11/7~ 11/1~ 10:30 The Happos Family Season 2 We Bare Bears We Bare Bears 10:00 The New Looney Tunes Show The New Looney Tunes Show 10:40 Pingu in the City Bravest Warriors Bravest Warriors 11:00 Baby Looney Tunes 11:30 Unikitty! 11/15~Eagle Talon NEO(J) 11:30 12:00 Thomas and Friends 12:00 12:30 The Happos Family Season 2 12:30 12:40 Pingu in the City 13:00 Baby Looney Tunes Dorothy and the Wizard of Oz Unikitty! 13:00 13:30 Grizzy and the Lemmings Oggy & the Cockroaches (season 5) 13:30 14:00 The Powerpuff Girls 14:00 We Bare Bears The Powerpuff Girls 14:30 Sylvester & Tweety Mysteries 14:30 15:00 Buck & Buddy 15:00 15:15 Uncle Grandpa The New Looney Tunes Show Uncle Grandpa 15:30 15:30 16:00 16:00 Sergeant Keroro(J) Tom & Jerry series 16:30 16:30 17:00 17:00 Adventure Time The Amazing World of Gumball 17:30 17:30 18:00 18:00 The Amazing World of Gumball TEEN TiTANS GO! 18:30 18:30 19:00 19:00 Tom & Jerry series Teen -

Definition of Pantomime: A Theatrical Entertainment, Mainly for Children

Definition of Pantomime: A theatrical entertainment, mainly for children, which involves music, topical jokes, and slapstick comedy and is based on a fairy tale or nursery story, usually produced around Christmas. A typical Pantomime storyline: Normally, a pantomime is an adapted fairytale so it is usually a magical love story which involves something going wrong (usually the fault of an evil baddy) but the ending (often after a fight between good and evil) is always happy and results in true love. Key characters in Pantomime: The female love interest, e.g Snow White, Cinderella etc The Handsome Prince e.g Prince Charming The evil character e.g the evil Queen in Snow White The faithful sidekick - e.g Buttons in Cinderella The Pantomime Dame - provides most of the comedy - an exaggerated female, always played by a man for laughs How to act in a pantomime style: 1. Your character is an over-the-top type’, not a real person, so exaggerate as much as you can, in gesture, voice and movement 2. Speak to the audience - if you are a ‘Goody’, your character must be likeable or funny. If you are a ‘Baddy’, insult your audience, make them dislike you from the start. 3. There is always a narrator - make sure she knows speaks confidently and knows the story well. 4. Encourage the audience to be involved by asking for the audience’s help, e.g “If you see that naughty boy will you tell me?” 5. If you are playing that ‘naughty boy’, make eye contact with the audience and creep on stage. -

February 20, 2015 Vol. 119 No. 8

VOL. 119 - NO. 8 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, FEBRUARY 20, 2015 $.35 A COPY WATCHING WHILE THE WORLD BURNS A Winter Poem by Sal Giarratani It’s winter in Massachusetts Back when Jack Kennedy and the gentle breezes blow. was a young man, he penned At seventy miles an hour a great piece of non-fiction entitled, “While England and at thirty-five below. Sleeps” in which he warned Oh how I love Massachusetts the world that to sit back and when the snow’s up to your butt. watch evil like a helpless bystander led to World War II. You take a breath of winter While Hitler and the Nazis and your nose gets frozen shut. slaughtered millions of inno- Yes, the weather here is wonderful cent people, including six so I guess I’ll hang around. million Jews, the West sat on its hands, but eventually I could never leave Massachusetts evil has a way of growing if cuz I’m frozen to the ground. left alone. I see the very same thing — Author Unknown taking place as I write this commentary. Just over the Presidents’ Day holiday weekend, 21 Coptic Chris- when it comes to his objec- puts a target on Europe and tians were rounded up by tivity on Radical Islam who especially Rome, Italy. Our ISIS and all dressed in or- are trying to create a global president may not believe ange jumpsuits had their caliphate when Jewish pa- we are in a war, but we are heads severed on video for trons at a Paris deli are ex- thanks to the other side. -

Download Download

Polish Feature Film after 1989 By Tadeusz Miczka Spring 2008 Issue of KINEMA CINEMA IN THE LABYRINTH OF FREEDOM: POLISH FEATURE FILM AFTER 1989 “Freedom does not exist. We should aim towards it but the hope that we will be free is ridiculous.” Krzysztof Kieślowski1 This essay is the continuation of my previous deliberations on the evolution of the Polish feature film during socialist realism, which summarized its output and pondered its future after the victory of the Solidarity movement. In the paper “Cinema Under Political Pressure…” (1993), I wrote inter alia: “Those serving the Tenth Muse did not notice that martial law was over; they failed to record on film the takeover of the government by the political opposition in Poland. […] In the new political situation, the society has been trying to create a true democratic order; most of the filmmakers’ strategies appeared to be useless. Incipit vita nova! Will the filmmakers know how to use the freedom of speech now? It is still too early toanswer this question clearly, but undoubtedly there are several dangers which they face.”2 Since then, a dozen years have passed and over four hundred new feature films have appeared on Polish cinema screens, it isnow possible to write a sequel to these reflections. First of all it should be noted that a main feature of Polish cinema has always been its reluctance towards genre purity and display of the filmmaker’s individuality. That is what I addressed in my earlier article by pointing out the “authorial strategies.” It is still possible to do it right now – by treating the authorial strategy as a research construct to be understood quite widely: both as the “sphere of the director” or the subjective choice of “authorial role,”3 a kind of social strategy or social contract.4 Closest to my approach is Tadeusz Lubelski who claims: “[…] The practical application of authorial strategies must be related to the range of social roles functioning in the culture of a given country and time. -

Free-Digital-Preview.Pdf

THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION AND VFX January 2013 ™ $7.95 U.S. 01> 0 74470 82258 5 www.animationmagazine.net THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION AND VFX January 2013 ™ The Return of The Snowman and The Littlest Pet Shop + From Up on The Visual Wonders Poppy Hill: of Life of Pi Goro Miyazaki’s $7.95 U.S. 01> Valentine to a Gone-by Era 0 74470 82258 5 www.animationmagazine.net 4 www.animationmagazine.net january 13 Volume 27, Issue 1, Number 226, January 2013 Content 12 22 44 Frame-by-Frame Oscars ‘13 Games 8 January Planner...Books We Love 26 10 Things We Loved About 2012! 46 Oswald and Mickey Together Again! 27 The Winning Scores Game designer Warren Spector spills the beans on the new The composers of some of the best animated soundtracks Epic Mickey 2 release and tells us how much he loved Features of the year discuss their craft and inspirations. [by Ramin playing with older Disney characters and long-forgotten 12 A Valentine to a Vanished Era Zahed] park attractions. Goro Miyazaki’s delicate, coming-of-age movie From Up on Poppy Hill offers a welcome respite from the loud, CG world of most American movies. [by Charles Solomon] Television Visual FX 48 Building a Beguiling Bengal Tiger 30 The Next Little Big Thing? VFX supervisor Bill Westenhofer discusses some of the The Hub launches its latest franchise revamp with fashion- mind-blowing visual effects of Ang Lee’s Life of Pi. [by Events forward The Littlest Pet Shop. -

The Field Guide to Sponsored Films

THE FIELD GUIDE TO SPONSORED FILMS by Rick Prelinger National Film Preservation Foundation San Francisco, California Rick Prelinger is the founder of the Prelinger Archives, a collection of 51,000 advertising, educational, industrial, and amateur films that was acquired by the Library of Congress in 2002. He has partnered with the Internet Archive (www.archive.org) to make 2,000 films from his collection available online and worked with the Voyager Company to produce 14 laser discs and CD-ROMs of films drawn from his collection, including Ephemeral Films, the series Our Secret Century, and Call It Home: The House That Private Enterprise Built. In 2004, Rick and Megan Shaw Prelinger established the Prelinger Library in San Francisco. National Film Preservation Foundation 870 Market Street, Suite 1113 San Francisco, CA 94102 © 2006 by the National Film Preservation Foundation Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Prelinger, Rick, 1953– The field guide to sponsored films / Rick Prelinger. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-9747099-3-X (alk. paper) 1. Industrial films—Catalogs. 2. Business—Film catalogs. 3. Motion pictures in adver- tising. 4. Business in motion pictures. I. Title. HF1007.P863 2006 011´.372—dc22 2006029038 CIP This publication was made possible through a grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. It may be downloaded as a PDF file from the National Film Preservation Foundation Web site: www.filmpreservation.org. Photo credits Cover and title page (from left): Admiral Cigarette (1897), courtesy of Library of Congress; Now You’re Talking (1927), courtesy of Library of Congress; Highlights and Shadows (1938), courtesy of George Eastman House. -

America Animated: Nationalist Ideology in Warner

AMERICA ANIMATED: NATIONALIST IDEOLOGY IN WARNER BROTHERS’ ANIMANIACS Except where reference is made to the work of others, the work described in this thesis is my own or was done in collaboration with my advisory committee. This thesis does not include proprietary or classified information. ___________________________ Megan Elizabeth Rector Certificate of Approval: ____________________________ ____________________________ Susan Brinson Kristen Hoerl, Chair Professor Assistant Professor Communication and Journalism Communication and Journalism _________________________ ____________________________ George Plasketes George T. Flowers Professor Dean Communication and Journalism Graduate School AMERICA ANIMATED: NATIONALIST IDEOLOGY IN WARNER BROTHERS’ ANIMANIACS Megan Elizabeth Rector A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of the Arts Auburn, Alabama December 19, 2008 AMERICA ANIMATED: NATIONALIST IDEOLOGY IN WARNER BROTHERS’ ANIMANIACS Megan Elizabeth Rector Permission is granted to Auburn University to make copies of this thesis at its discretion, upon request of individuals or institutions at their expense. The author reserves all publication rights. _____________________________ Signature of Author _____________________________ Date of Graduation iii VITA Megan Elizabeth Rector, daughter of Timothy Lawrence Rector and Susan Andrea Rector, was born June 6, 1984, in Jacksonville, Florida. She graduated from Lewis-Palmer High School with distinction -

Glorious Technicolor: from George Eastman House and Beyond Screening Schedule June 5–August 5, 2015 Friday, June 5 4:30 the G

Glorious Technicolor: From George Eastman House and Beyond Screening Schedule June 5–August 5, 2015 Friday, June 5 4:30 The Garden of Allah. 1936. USA. Directed by Richard Boleslawski. Screenplay by W.P. Lipscomb, Lynn Riggs, based on the novel by Robert Hichens. With Marlene Dietrich, Charles Boyer, Basil Rathbone, Joseph Schildkraut. 35mm restoration by The Museum of Modern Art, with support from the Celeste Bartos Fund for Film Preservation; courtesy The Walt Disney Studios. 75 min. La Cucaracha. 1934. Directed by Lloyd Corrigan. With Steffi Duna, Don Alvarado, Paul Porcasi, Eduardo Durant’s Rhumba Band. Courtesy George Eastman House (35mm dye-transfer print on June 5); and UCLA Film & Television Archive (restored 35mm print on July 21). 20 min. [John Barrymore Technicolor Test for Hamlet]. 1933. USA. Pioneer Pictures. 35mm print from The Museum of Modern Art. 5 min. 7:00 The Wizard of Oz. 1939. USA. Directed by Victor Fleming. Screenplay by Noel Langley, Florence Ryerson, Edgar Allan Woolf, based on the book by L. Frank Baum. Music by Harold Arlen, E.Y. Harburg. With Judy Garland, Frank Morgan, Ray Bolger, Bert Lahr, Ray Bolger, Margaret Hamilton, Billie Burke. 35mm print from George Eastman House; courtesy Warner Bros. 102 min. Saturday, June 6 2:30 THE DAWN OF TECHNICOLOR: THE SILENT ERA *Special Guest Appearances: James Layton and David Pierce, authors of The Dawn of Technicolor, 1915-1935 (George Eastman House, 2015). James Layton and David Pierce illustrate Technicolor’s origins during the silent film era. Before Technicolor achieved success in the 1930s, the company had to overcome countless technical challenges and persuade cost-conscious producers that color was worth the extra effort and expense.