Kant's Proof of a Universal Principle of Causality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

Duns Scotus on the Common Nature and the Individual Differentia

c Peter King, Philosophical Topics 20 (1992), 50–76 DUNS SCOTUS ON THE COMMON NATURE* Introduction COTUS holds that in each individual there is a principle that accounts for its being the very thing it is and a formally S distinct principle that accounts for its being the kind of thing it is; the former is its individual differentia, the latter its common nature.1 These two principles are not on a par: the common nature is prior to the individual differentia, both independent of it and indifferent to it. When the individual differentia is combined with the common nature, the result is a concrete individual that really differs from all else and really agrees with others of the same kind. The individual differentia and the common nature thereby explain what Scotus takes to stand in need of explanation: the indi- viduality of Socrates on the one hand, the commonalities between Socrates * An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 26th International Congress on Medieval Studies, sponsored by the Medieval Institute, held at Western Michigan University 9–12 May 1991. All translations are my own. Scotus’s writings may be found in the following editions: (1) Vaticana: Iohannis Duns Scoti Doctoris Subtilis et Mariani opera omnia, ed. P. Carolus Bali¸cet alii, Typis Polyglottis Vaticanae 1950– Vols. I–VII, XVI–XVIII. (2) Wadding-Viv`es: Joannis Duns Scoti Doctoris Subtilis Ordinis Minorum opera omnia, ed. Luke Wadding, Lyon 1639; republished, with only slight alterations, by L. Viv`es,Paris 1891–1895. Vols. I–XXVI. References are to the Vatican edition wherever possible, to the Wadding-Viv`esedition otherwise. -

Hume's Objects After Deleuze

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School March 2021 Hume's Objects After Deleuze Michael P. Harter Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Harter, Michael P., "Hume's Objects After Deleuze" (2021). LSU Master's Theses. 5305. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/5305 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HUME’S OBJECTS AFTER DELEUZE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies by Michael Patrick Harter B.A., California State University, Fresno, 2018 May 2021 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Human beings are wholly dependent creatures. In our becoming, we are affected by an incredible number of beings who aid and foster our growth. It would be impossible to devise a list of all such individuals. However, those who played imperative roles in the creation of this work deserve their due recognition. First, I would like to thank my partner, Leena, and our pets Merleau and the late Kiki. Throughout the ebbs and flows of my academic career, you have remained sources of love, joy, encouragement, and calm. -

Causality and Determinism: Tension, Or Outright Conflict?

1 Causality and Determinism: Tension, or Outright Conflict? Carl Hoefer ICREA and Universidad Autònoma de Barcelona Draft October 2004 Abstract: In the philosophical tradition, the notions of determinism and causality are strongly linked: it is assumed that in a world of deterministic laws, causality may be said to reign supreme; and in any world where the causality is strong enough, determinism must hold. I will show that these alleged linkages are based on mistakes, and in fact get things almost completely wrong. In a deterministic world that is anything like ours, there is no room for genuine causation. Though there may be stable enough macro-level regularities to serve the purposes of human agents, the sense of “causality” that can be maintained is one that will at best satisfy Humeans and pragmatists, not causal fundamentalists. Introduction. There has been a strong tendency in the philosophical literature to conflate determinism and causality, or at the very least, to see the former as a particularly strong form of the latter. The tendency persists even today. When the editors of the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy asked me to write the entry on determinism, I found that the title was to be “Causal determinism”.1 I therefore felt obliged to point out in the opening paragraph that determinism actually has little or nothing to do with causation; for the philosophical tradition has it all wrong. What I hope to show in this paper is that, in fact, in a complex world such as the one we inhabit, determinism and genuine causality are probably incompatible with each other. -

René Descartes: Father of Modern Philosophy and Scholasticism

René Descartes: Father of Modern Philosophy and Scholasticism Sarah Venable Course: Philosophy 301 Instructor: Dr. Barbara Forrest Assignment: Research Paper For centuries, the Roman Catholic Church completely dominated European thought. It had become the most powerful ruling force, leaving monarchs susceptible to its control through the threat of excommunication. For the everyday European, contradicting or questioning any aspect of Church doctrine could result in imprisonment, or even death. Scholars were bound by fear to avoid appearing too radical. However, the modern academic need not fear such retribution today. Learning has moved from the control of the Church and has become secularized due in part to the work of such thinkers as Descartes. René Descartes, who was interested in both science and philosophy, introduced his readers to the idea of separating academic knowledge from religious doctrine. He claimed science filled with uncertainty and myth could never promote learning or the advancement of society. Descartes responded to the growing conflict between these two forces with an attempt to bring clarity. He was willing to challenge the accepted ideas of his day and introduce change. Religion had not been separate from science in the past. By philosophy and science using reason as its cornerstone, science effected a substantial increase in knowledge. After a period of widespread illiteracy, Europe began to move forward in education by rediscovering Greek and Roman texts filled with science, mathematics, and philosophy. As time progressed and learning increased, the Church began to loosen its iron grip over the people. Church officials recognized a need to educate people as long as subject material was well controlled. -

Studies on Causal Explanation in Naturalistic Philosophy of Mind

tn tn+1 s s* r1 r2 r1* r2* Interactions and Exclusions: Studies on Causal Explanation in Naturalistic Philosophy of Mind Tuomas K. Pernu Department of Biosciences Faculty of Biological and Environmental Sciences & Department of Philosophy, History, Culture and Art Studies Faculty of Arts ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki, in lecture room 5 of the University of Helsinki Main Building, on the 30th of November, 2013, at 12 o’clock noon. © 2013 Tuomas Pernu (cover figure and introductory essay) © 2008 Springer Science+Business Media (article I) © 2011 Walter de Gruyter (article II) © 2013 Springer Science+Business Media (article III) © 2013 Taylor & Francis (article IV) © 2013 Open Society Foundation (article V) Layout and technical assistance by Aleksi Salokannel | SI SIN Cover layout by Anita Tienhaara Author’s address: Department of Biosciences Division of Physiology and Neuroscience P.O. Box 65 FI-00014 UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI e-mail [email protected] ISBN 978-952-10-9439-2 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-9440-8 (PDF) ISSN 1799-7372 Nord Print Helsinki 2013 If it isn’t literally true that my wanting is causally responsible for my reaching, and my itching is causally responsible for my scratching, and my believing is causally responsible for my saying … , if none of that is literally true, then practically everything I believe about anything is false and it’s the end of the world. Jerry Fodor “Making mind matter more” (1989) Supervised by Docent Markus -

Causation As Folk Science

1. Introduction Each of the individual sciences seeks to comprehend the processes of the natural world in some narrow do- main—chemistry, the chemical processes; biology, living processes; and so on. It is widely held, however, that all the sciences are unified at a deeper level in that natural processes are governed, at least in significant measure, by cause and effect. Their presence is routinely asserted in a law of causa- tion or principle of causality—roughly, that every effect is produced through lawful necessity by a cause—and our ac- counts of the natural world are expected to conform to it.1 My purpose in this paper is to take issue with this view of causation as the underlying principle of all natural processes. Causation I have a negative and a positive thesis. In the negative thesis I urge that the concepts of cause as Folk Science and effect are not the fundamental concepts of our science and that science is not governed by a law or principle of cau- sality. This is not to say that causal talk is meaningless or useless—far from it. Such talk remains a most helpful way of conceiving the world, and I will shortly try to explain how John D. Norton that is possible. What I do deny is that the task of science is to find the particular expressions of some fundamental causal principle in the domain of each of the sciences. My argument will be that centuries of failed attempts to formu- late a principle of causality, robustly true under the introduc- 1Some versions are: Kant (1933, p.218) "All alterations take place in con- formity with the law of the connection of cause and effect"; "Everything that happens, that is, begins to be, presupposes something upon which it follows ac- cording to a rule." Mill (1872, Bk. -

Sum, Ergo Cogito: Nietzsche Re-Orders Descartes

Aporia vol. 25 no. 2—2015 Sum, Ergo Cogito: Nietzsche Re-orders Descartes JONAS MONTE I. Introduction ietzsche’s aphorism 276 in The Gay Science addresses Descartes’ epistemological scheme: “I still live, I still think: NI still have to live, for I still have to think. Sum, ergo cogito: cogito, ergo sum” (GS 223). Ironically, Nietzsche inverts the logic in Descartes’ famous statement “Cogito, ergo sum” as a caustic way, yet poetic and stylish, of creating his own statement.1 He then delivers his critique by putting his own version prior to that of Descartes. Here, Nietzsche’s critique can be interpreted as a twofold overlap- ping argument. First, by reversing Descartes’ axiom into “Sum, ergo cogito,” Nietzsche stresses that in fact a social ontology (which includes metaphysical, logical, linguistic, and conceptual elements) has been a condition that makes possible Descartes’ inference of human existence from such pre-established values. Here, Descartes seems not to have applied his methodical doubt completely, since to arrive 1 In light of Nietzsche’s inversion, this paper seeks to analyse Descartes’ Meditation Project, in effect, the cogito as a device in itself. It does not consider the project’s metaphysical background, including the issue of Descartes’ substance dualism. For an introduction to Cartesian dualism, see Justin Skirry, “René Descartes: The Mind-Body Distinction,” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Jonas Monte is a senior currently studying in a joint honors program in philosophy and political science at the University of Ottawa, Canada. His primary philosophical interests are ethics, political philosophy, Nietzsche, and early modern philosophy. After graduation, Jonas plans to pursue a PhD in philosophy. -

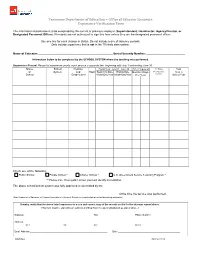

Experience Verification Form

Tennessee Department of Education – Office of Educator Licensure Experience Verification Form The information listed below is to be completed by the current or previous employer (Superintendent, Headmaster, Agency Director, or Designated Personnel Officer). Principals are not authorized to sign this form unless they are the designated personnel officer. Use one line for each change in status. Do not include leave of absence periods. Only include experience that is not in the TN state data system. Name of Educator: ________________________________________________ Social Security Number: _________________________ Information below to be completed by the SCHOOL SYSTEM where the teaching was performed. Experience Record: Please list experience yearly, each year on a separate line, beginning with July 1 and ending June 30. Name School Position Fiscal Year, July 01 - June 30 Time Employed % Time, Total of System and State Beginning Date Ending Date Months / Days Ex. Part-time, Days in Month/Day/Year Month/Day/Year Full-time School Year School Grade Level Per Year Check one of the following: Public School Private School * Charter School * U.S. Government Service Teaching Program * ** Please note: If non-public school you must identify accreditation. The above school/school system was fully approved or accredited by the ____________________________________________________________________ at the time the service was performed. (State Department of Education, or Regional Association of Colleges & Schools, or recognized private school accrediting -

Moral Relativism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2020 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Carlo Alvaro CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/583 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Abstract This paper is a response to Park Seungbae’s article, “Defence of Cultural Relativism”. Some of the typical criticisms of moral relativism are the following: moral relativism is erroneously committed to the principle of tolerance, which is a universal principle; there are a number of objective moral rules; a moral relativist must admit that Hitler was right, which is absurd; a moral relativist must deny, in the face of evidence, that moral progress is possible; and, since every individual belongs to multiple cultures at once, the concept of moral relativism is vague. Park argues that such contentions do not affect moral relativism and that the moral relativist may respond that the value of tolerance, Hitler’s actions, and the concept of culture are themselves relative. In what follows, I show that Park’s adroit strategy is unsuccessful. Consequently, moral relativism is incoherent. Keywords: Moral relativism; moral absolutism; objectivity; tolerance; moral progress 2 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Moral relativism is a meta-ethical theory according to which moral values and duties are relative to a culture and do not exist independently of a culture. -

Philosophy of Chemistry: an Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 434 811 SE 062 822 AUTHOR Erduran, Sibel TITLE Philosophy of Chemistry: An Emerging Field with Implications for Chemistry Education. PUB DATE 1999-09-00 NOTE 10p.; Paper presented at the History, Philosophy and Science Teaching Conference (5th, Pavia, Italy, September, 1999). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Chemistry; Educational Change; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Philosophy; Science Curriculum; *Science Education; *Science Education History; *Science History; Scientific Principles; Secondary Education; Teaching Methods ABSTRACT Traditional applications of history and philosophy of science in chemistry education have concentrated on the teaching and learning of "history of chemistry". This paper considers the recent emergence of "philosophy of chemistry" as a distinct field and explores the implications of philosophy of chemistry for chemistry education in the context of teaching and learning chemical models. This paper calls for preventing the mutually exclusive development of chemistry education and philosophy of chemistry, and argues that research in chemistry education should strive to learn from the mistakes that resulted when early developments in science education were made separate from advances in philosophy of science. Contains 54 references. (Author/WRM) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ******************************************************************************** 1 PHILOSOPHY OF CHEMISTRY: AN EMERGING FIELD WITH IMPLICATIONS FOR CHEMISTRY EDUCATION PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS Office of Educational Research and improvement BEEN GRANTED BY RESOURCES INFORMATION SIBEL ERDURAN CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproducedas ceived from the person or organization KING'S COLLEGE, UNIVERSITYOF LONDON originating it. -

Universal Causality Graphs: a Precise Happens-Before Model for Detecting Bugs in Concurrent Programs

Universal Causality Graphs: A Precise Happens-Before Model for Detecting Bugs in Concurrent Programs Vineet Kahlon and Chao Wang NEC Laboratories America, Princeton, NJ 08540, USA Abstract. Triggering errors in concurrent programs is a notoriously difficult task. A key reason for this is the behavioral complexity resulting from the large number of interleavings of operations of different threads. Efficient static tech- niques, therefore, play a critical role in restricting the set of interleavings that need be explored in greater depth. The goal here is to exploit scheduling con- straints imposed by synchronization primitives to determine whether the property at hand can be violated and report schedules that may lead to such a violation. Towards that end, we propose the new notion of a Universal Causality Graph (UCG) that given a correctness property P , encodes the set of all (statically) fea- sible interleavings that may violate P . UCGs provide a unified happens-before model by capturing causality constraints imposed by the property at hand as well as scheduling constraints imposed by synchronization primitives as causality con- straints. Embedding all these constraints into one common framework allows us to exploit the synergy between the constraints imposed by different synchroniza- tion primitives, as well as between the constraints imposed by the property and the primitives. This often leads to the removal of significantly more redundant in- terleavings than would otherwise be possible. Importantly, it also guarantees both soundness and completeness of our technique for identifying statically feasible interleavings. As an application, we demonstrate the use of UCGs in enhancing the precision and scalability of predictive analysis in the context of runtime veri- fication of concurrent programs.