Looking Through the Upside Down: Hyperpostmodernism and Trans-Mediality in the Duffer Brothers' Stranger Things Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

Teen-Noir – Veronica Mars Og Den Moderne Ungdomsserie (PDF)

Teen Noir – Veronica Mars og den moderne ungdomsserie AF MICHAEL HØJER I 2004 havde den amerikanske ungdomskanal UPN premiere på Rob Tho- mas’ ungdomsserie Veronica Mars (2004-2007). Serien foregår i den fikti- ve, sydcaliforniske by Neptune og handler om teenagepigen Veronica Mars (Kristen Bell), der arbejder som privatdetektiv, samtidig med at hun går på high school. Trods det faktum, at Veronica Mars havde en dedikeret fanskare bag sig, befandt den sig i samtlige tre sæsoner blandt de mindst sete tv-serier i USA. Da tendensen kun forværredes hen mod afslutningen af tredje sæ- son, var der ikke længere økonomisk grobund for at fortsætte (Van De Kamp 2007). Serien blev sat på pause, inden de sidste fem afsnit blev vist, hvor- efter CW (en fusion af det tidligere UPN og en anden ungdomsorienteret ka- nal ved navn WB) lukkede permanent for kassen. Selvom seriens hardcore fans sendte 10.000 Marsbarer til CW’s hovedkontor i et forsøg på at genop- live serien, og selvom der var flere forsøg fra produktionsholdets side på at fortsætte den enten via tv, en opfølgende film eller endda en tegneserie, er dvd-udgivelsen af Veronica Mars’ tre sæsoner det sidste, man har set til Rob Thomas’ serie. Foruden sin dedikerede fanskare – der bl.a. talte prominente personer som forfatteren Stephen King, filminstruktøren Kevin Smith og Joss Whe- don, der skabte både Firefly og Buffy the Vampire Slayer (UPN/WB, 1997- 2003)1 – var også anmelderne hurtige til at se seriens kvaliteter. Specielt de første to sæsoner af Veronica Mars blev meget vel modtaget. Større, to- neangivende amerikanske medier som LA Weekly, The Village Voice, New York Times og Time roste alle serien med ord som ”remarkably innovative”, ”promising”, ”smart, engaging” og ”genre-defying”. -

Bull Dogs' Quintessential Team Player

BULL DOG OCT. 1 - NOV. 4, 2018 BULLETIN VOL. 8, ISSUE 3 NEWS AND INFORMATION ABOUT COLUMBUS NORTH HIGH SCHOOL ATHLETICS IN THIS ISSUE Fall Scoreboard ............. 2 Football .......................... 4 Boys Soccer .................. 9 Girls Soccer ................... 11 Cross Country ................ 15 Girls Golf ........................ 17 Boys Tennis ................... 19 Volleyball ....................... 23 Cheerleaders ................. 25 Booster Club .................. 29 Athletic Staff .................. 31 MR. INTENSITY: Kevin Lin displays ferocity while remaining analytical while competing for the Columbus North boys’ tennis team. The senior – a two-time team most valuable player – carries a 12-5 record this season at No. 1 singles entering regional competition. BULL DOGS’ QUINTESSENTIAL TEAM PLAYER FORE!: Sophomore Nathaly Munnicha earned Columbus North senior thrives on court, excels in leadership role for boys’ tennis team all-state honors girls golf in 2018. CN GIRLS ole model. Kevin Lin. Lin, who hopes for a career in sports medicine GOLF PLACES Kevin Lin. Role model. or as an orthopedic surgeon, said he strives to R The Columbus North senior boys’ bring proper focus and footwork to each match. SEVENTH AT tennis player and the concept go hand-in-hand, “I’m intense when I play,” said Lin, who is STATE MEET according to Bull Dogs coach Kendal Hammel. considering Indiana, Purdue, Columbia, Michigan Lin has been the epitome of a quality player and Duke as possible college choices. “I try to Sophomore Nathaly Munnicha shot throughout his career, compiling a 58-31 play 100 percent all the time and try not to be a 78 on Sept. 29 for a two-round total record in varsity matches as four-year varsity sloppy or lazy. -

Leslie Caron

Paddock Suite, The Courtyard, 55 Charterhouse Street, London, EC1M 6HA p: + 44 (0) 20 73360351 e: [email protected] Phone: + 44 (0) 20 73360351 Email: [email protected] Leslie Caron Photo: John Mann Location: London, United Kingdom Eye Colour: Blue Height: 5'1" (154cm) Hair Colour: Dark Brown Playing Age: Over 60 years Hair Length: Long Appearance: White Film Film, Suzanne de Persand, Le Divorce, Merchant Ivory Productions, James Ivory Film, Madame Audel, Chocolat, Miramax Films, Lasse Hallström Film, Regine De Chantelle, The Reef, CBS, Robert Allan Ackerman Film, Marguerite, Let It Be Me, Savoy Pictures, Eleanor Begstein Film, Katie Parker, Funny Bones, Hollywood Pictures, Peter Chelsom Film, Elizabeth Prideaux, Damage, Studio Canal, Louis Malle Film, Waitress, Guns, Malibu Bay Films, Andy Sidaris Film, Jane Hillary, Courage Mountain, Triumph Films, Christopher Leitch Film, Henia Liebskind, Dangerous Moves, Gaumont, Richard Dembo Film, Mother, Imperative, TeleCulture, Krzysztof Zanussi Film, uncredited, Chanel Solitaire, United Film Distribution Company, George Kaczender Film, Lucille Berger, All Stars Film, Dr. Sammy Lee, Goldengirl, AVCO Embassy Pictures, Joseph Sargent Film, Nicole, Nicole, Troma Entertainment, István Ventilla Film, Alla Nazimova, Valentino, United Artists, Ken Russell Film, Véra, The Man Who Loved Women, United Artists, François Truffaut Film, Céleste, Surreal Estate, Caribou Films, Eduardo de Gregorio Film, Katherine Creighton, Chandler, MGM, Paul Magwood Film, Sister Mary, Madron, Four Star-Excelsior, Jerry Hopper -

Undercover Footage from Sydney Slaughterhouse Released As NSW & Federal Govt Seek to Criminalise Whistleblowing

MEDIA RELEASE – 29 AUGUST 2019 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘Horrific but legal’ undercover footage from Sydney slaughterhouse released as NSW & Federal Govt seek to criminalise whistleblowing Animal rights organisations Aussie Farms and Animals Within have released new footage captured by a hidden body-worn camera at the Picton Meatworx (formerly Wollondilly Abattoir), a multi-species slaughterhouse south of Sydney, amid efforts by the NSW and Federal Governments to severely increase penalties for activists who expose animal cruelty. View the footage: 8 minute summary edit: https://www.aussiefarms.org.au/videos?id=yq7rtdnf07 25 minute full edit: https://www.aussiefarms.org.au/videos?id=pneynwbwc9 The footage includes: the use of excruciating carbon dioxide gas chambers on pigs, goats and sheep; repeated failure of captive bolt stunning, with one pig shot eight times while screaming in pain; twisting and breaking of cows’ tails to force them to walk into the knockbox; animals regularly witnessing those before them being killed and consequently trying to escape. It was recorded by a university student undertaking a placement at the facility as part of their animal science degree. Chris Delforce, Executive Director of Aussie Farms and director of Dominion: “This is some of the most damning Australian footage I’ve ever seen, and yet, it’s completely legal. There are very minimal laws in place to protect animals in facilities like these, which is the complete opposite to what most consumers are led to believe; while there’s a general offence for animal cruelty in the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act (POCTA) NSW, farms and slaughterhouses are exempt from this if they follow basic codes of practice which effectively legalise cruelty that regular citizens wouldn’t be able to get away with.” “The code of practice relating to slaughterhouses is only a model code, intended as non-enforceable guidelines for states and territories to develop their own legislation, but 18 years later none have done so. -

Sunday Morning Grid 9/24/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

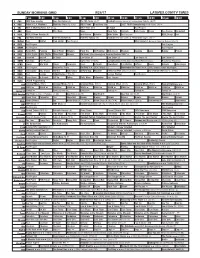

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/24/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Houston Texans at New England Patriots. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Presidents Cup 2017 TOUR Championship Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Rock-Park Outback Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football New York Giants at Philadelphia Eagles. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program MLS Soccer LA Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Cooking Jazzy Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons DW News: Live Coverage of German Election 2017 Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La Comadrita (1978, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana The Reef ›› (2006, Niños) (G) Remember the Titans ››› (2000, Drama) Denzel Washington. -

Musikliste Zu Terra X „Unsere Wälder“ Titel Sortiert in Der Reihenfolge, in Der Sie in Der Doku Zu Hören Sind

Z Musikliste zu Terra X „Unsere Wälder“ Titel sortiert in der Reihenfolge, in der sie in der Doku zu hören sind. Folge 1 MUSIK - Titel CD / Interpret Composer Trailer Terra X Trailer Terra X Main Title Theme – Westworld - Season 1 / Ramin Djawadi Westworld Ramin Djawadi Dr. Ford Westworld - Season 1 / Ramin Djawadi Ramin Djawadi Photos in the Woods Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon Eleven Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon Race To Mark's Flat Bridget Jones's Baby / Craig Armstrong Craig Armstrong Boggis, Bunce and Fantastic Mr. Fox / Alexandre Desplat Alexandre Desplat Bean Hibernation Pod 1625 Passengers / Thomas Newman Thomas Newman Jack It Up Steve Jobs / Daniel Pemberton Daniel Pemberton The Dream and the Collateral Beauty / Theodore Shapiro Letters Theodore Shapiro Reporters Swarm Confirmation / Harry Gregson Williams Harry Gregson Williams Persistence Burnt / Rob Simonsen Rob Simonsen Introducing Howard Collateral Beauty / Theodore Shapiro Inlet Theodore Shapiro The Dream and the Collateral Beauty / Theodore Shapiro Theodore Shapiro Letters Main Title Theme – Westworld - Season 1 / Ramin Djawadi Westworld Ramin Djawadi Fell Captain Fantastic / Alex Somers Alex Somers Me Before You Me Before You / Craig Armstrong Craig Armstrong Orchestral This Isn't You Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon The Skylab Plan Steve Jobs / Daniel Pemberton Daniel Pemberton Photos in the Woods Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon Speight Lived Here The Knick (Season 2) / Cliff Martinez Cliff Martinez This Isn't You Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon 3 Minutes Of Moderat A New Beginning Captain Fantastic / Alex Somers Alex Somers 3 Minutes Of Moderat The Walk The Walk / Alan Silvestri Alan Silvestri Dr. -

Detectives with Pimples: How Teen Noir Is Crossing the Frontiers of the Traditional Noir Films1

Detectives with pimples: How teen noir is crossing the frontiers of the traditional noir films1 João de Mancelos (Universidade da Beira Interior) Palavras-chave: Teen noir, Veronica Mars, cinema noir, reinvenção, feminismo Keywords: Teen noir, Veronica Mars, noir cinema, reinvention, feminism 1. “If you’re like me, you just keep chasing the storm” In the last ten years, films and TV series such as Heathers (1999), Donnie Darko (2001), Brick (2005) or Veronica Mars (2004-2007) have become increasingly popular and captivated cult audiences, both in the United States and in Europe, while arousing the curiosity of critics. These productions present characters, plots, motives and a visual aesthetic that resemble the noir films created between 1941, when The Maltese Falcon premiered, and 1958, when Touch of Evil was released. The new films and series retain, for instances, characters like the femme fatale, who drags men to a dreadful destiny; the good-bad girl, who does not hesitate in resorting to dubious methods in order to achieve morally correct objectives; and the lonely detective, now a troubled adolescent — as if Sam Spade had gone back to High School. In the first decade of our century, critics coined the expression teen noir to define this new genre or, in my opinion, subgenre, since it retains numerous traits of the classic film noir, especially in its contents, thus not creating a significant rupture. In this article, I intend to a) examine the common elements between teen noir series and classic noir films; b) analyze how this new production reinvents or subverts the characteristics of the old genre, generating a sense of novelty; c) detect some of the numerous intertextual references present in Veronica Mars, which may lead young viewers to investigate other series, movies or books. -

Stranger Things 2 *

WONDER VIEW Episode #209 "Chapter Nine: The Gate" by The Duffer Brothers Directed by The Duffer Brothers PRODUCTION DRAFT April 17, 2017 (WHITE) April 30, 2017 (BLUE) Copyright © 2017 Storybuilders, LLC. All rights reserved. No portion of this script may be performed, published, reproduced, sold, or distributed by any means or quoted or published in any medium, including on any website, without the prior written consent of Storybuilders, LLC. Disposal of this script copy does not alter any of the restrictions set forth above. Episode #209 04/30/17 WONDER VIEW "Chapter Nine: The Gate" REVISION HISTORY DATE COLOR PAGES PUBLISHED 04/17/17 PRODUCTION DRAFT FULL SCRIPT 04/30/17 (BLUE) CAST, SETS, 9, 10, 13, 14, 15, 15A, 28, 30, 37, 44, 45, 48, 49, 49A, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 55A, 63, 64, 67, 70/71 8FLiX.com SCREENPLAY DATABASE FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Episode #209 04/30/17 WONDER VIEW "Chapter Nine: The Gate" CAST LIST JOYCE BYERS POLICE CHIEF JIM HOPPER MIKE WHEELER NANCY WHEELER JONATHAN BYERS ELEVEN LUCAS SINCLAIR DUSTIN HENDERSON KAREN WHEELER WILL BYERS STEVE HARRINGTON MAX MAYFIELD BILLY HARGROVE (fka BILLY MAYFIELD) * DR. SAM OWENS TED WHEELER MURRAY BAUMAN * * MR. CLARKE CLAUDIA HENDERSON ERICA SINCLAIR MRS. HOLLAND MR. HOLLAND SUSAN HARGROVE (fka SUSAN MAYFIELD) * * * * CUTE GIRL STACEY TV NEWS ANCHOR MIDDLE SCHOOL BOY #1 * * 8FLiX.com SCREENPLAY DATABASE FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY Episode #209 04/30/17 WONDER VIEW "Chapter Nine: The Gate" SET LIST INTERIORS EXTERIORS BYERS HOUSE BYERS HOUSE HALLWAY BACK YARD/SHED JONATHAN'S ROOM DRIVEWAY -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 86Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 86TH ACADEMY AWARDS ABOUT TIME Notes Domhnall Gleeson. Rachel McAdams. Bill Nighy. Tom Hollander. Lindsay Duncan. Margot Robbie. Lydia Wilson. Richard Cordery. Joshua McGuire. Tom Hughes. Vanessa Kirby. Will Merrick. Lisa Eichhorn. Clemmie Dugdale. Harry Hadden-Paton. Mitchell Mullen. Jenny Rainsford. Natasha Powell. Mark Healy. Ben Benson. Philip Voss. Tom Godwin. Pal Aron. Catherine Steadman. Andrew Martin Yates. Charlie Barnes. Verity Fullerton. Veronica Owings. Olivia Konten. Sarah Heller. Jaiden Dervish. Jacob Francis. Jago Freud. Ollie Phillips. Sophie Pond. Sophie Brown. Molly Seymour. Matilda Sturridge. Tom Stourton. Rebecca Chew. Jon West. Graham Richard Howgego. Kerrie Liane Studholme. Ken Hazeldine. Barbar Gough. Jon Boden. Charlie Curtis. ADMISSION Tina Fey. Paul Rudd. Michael Sheen. Wallace Shawn. Nat Wolff. Lily Tomlin. Gloria Reuben. Olek Krupa. Sonya Walger. Christopher Evan Welch. Travaris Meeks-Spears. Ann Harada. Ben Levin. Daniel Joseph Levy. Maggie Keenan-Bolger. Elaine Kussack. Michael Genadry. Juliet Brett. John Brodsky. Camille Branton. Sarita Choudhury. Ken Barnett. Travis Bratten. Tanisha Long. Nadia Alexander. Karen Pham. Rob Campbell. Roby Sobieski. Lauren Anne Schaffel. Brian Charles Johnson. Lipica Shah. Jarod Einsohn. Caliaf St. Aubyn. Zita-Ann Geoffroy. Laura Jordan. Sarah Quinn. Jason Blaj. Zachary Unger. Lisa Emery. Mihran Shlougian. Lynne Taylor. Brian d'Arcy James. Leigha Handcock. David Simins. Brad Wilson. Ryan McCarty. Krishna Choudhary. Ricky Jones. Thomas Merckens. Alan Robert Southworth. ADORE Naomi Watts. Robin Wright. Xavier Samuel. James Frecheville. Sophie Lowe. Jessica Tovey. Ben Mendelsohn. Gary Sweet. Alyson Standen. Skye Sutherland. Sarah Henderson. Isaac Cocking. Brody Mathers. Alice Roberts. Charlee Thomas. Drew Fairley. Rowan Witt. Sally Cahill. -

No. 3 2018 Messengers from the Stars: on Science Fiction and Fantasy No

No. 3 2018 Messengers from the Stars: On Science Fiction and Fantasy No. 3 – 2018 Editorial Board | Adelaide Serras Ana Daniela Coelho Ana Rita Martins Angélica Varandas João Félix José Duarte Advisory Board | Adam Roberts (Royal Holloway, Univ. of London, UK) David Roas (Univ. Autónoma de Barcelona, Spain) Flávio García (Univ. do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) Henrique Leitão (Fac. de Ciências, Univ. de Lisboa, Portugal) Jonathan Gayles (Georgia State University, USA) Katherine Fowkes (High Point University, USA) Ljubica Matek (Univ. of Osijek, Croatia) Mª Cristina Batalha (Univ. do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) Susana Oliveira (Fac. de Arquitectura, Univ. de Lisboa, Portugal) Teresa Lopez-Pellisa (Univ. Autónoma de Barcelona, Spain) Copy Editors | Ana Rita Martins || David Klein Martins || João Félix || José Duarte Book Review | Diana Marques || Igor Furão || Mónica Paiva Editors Translator | Diogo Almeida Photography | Thomas Örn Karlsson Site | http://messengersfromthestars.letras.ulisboa.pt/journal/ Contact | [email protected] ISSN | 2183-7465 Editor | Centro de Estudos Anglísticos da Universidade de Lisboa | University of Lisbon Centre for English Studies Alameda da Universidade - Faculdade de Letras 1600-214 Lisboa - Portugal Messengers from the Stars: On Science Fiction and Fantasy Guest Editors Martin Simonson Raúl Montero Gilete Co-Editors No. 3 Angélica Varandas José Duarte TABLE OF CONTENTS EDITORIAL 5 GUEST EDITORS: MARTIN SIMONSON & RAÚL MONTERO GILETE 5 MONOGRAPH SECTION 9 A DEAL WITH THE DEVIL?: ZOMBIES VS. -

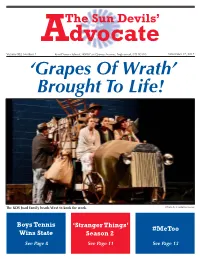

'Grapes of Wrath' Brought to Life!

The Sun Devils’ Advocate Volume XLI, Number 7 Kent Denver School, 4000 East Quincy Avenue, Englewood, CO 80110 November 17, 2017 ‘Grapes Of Wrath’ Brought To Life! The KDS Joad Family heads West to kook for work. Photo by Cordelia Lowrey Boys Tennis ‘Stranger Things’ #MeToo Wins State Season 2 See Page 8 See Page 11 See Page 13 News Las Vegas Pushes For Gun Regulations eral public, without any responsible measures by Henry Rogers or safeguards, and which the killer foreseeably used to such horrific results.” Following the tragic mass shootings in Las Vegas and San Antonio, there has been a recent Since the filing of the lawsuit, Democrats push from many gun control groups to see a in Congress have proposed legislation to ban change in gun regulation from Congress. After Bump Stocks, and both President Trump and the Las Vegas shooting, a powerful gun control the National Rifle Association (NRA) have group filed a lawsuit against the manufacturers been open to the idea of greater regulation. of ‘Bump Stocks,’ an instrument which was be- Unfortunately, the future does not hold any lieved to have been used by Stephen Paddock, promise that there will be any major changes the Las Vegas shooter, from the 32nd floor of regarding gun safety regulations at this time, Mandalay Bay Hotel. The purpose of a ‘Bump due to the NRA’s powerful lobbying influence Stock’ is to allow semi automatic guns to rapid on political leaders. fire bullets, making it more akin to automatic The NRA and Congress’s inability to im- weapons or machine guns.