LEGGED OWLS &Lpar;<I>STRIX RUFIPES</I>

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chelemys Megalonyx (Waterhouse, 1844) NOMBRE COMÚN: Rata Topo Del Matorral, Shrub Mole-Rat, Large Long-Clawed Mouse

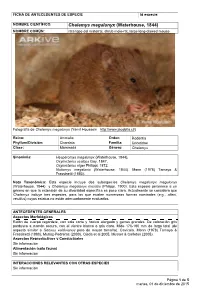

FICHA DE ANTECEDENTES DE ESPECIE Id especie: NOMBRE CIENTÍFICO: Chelemys megalonyx (Waterhouse, 1844) NOMBRE COMÚN: rata topo del matorral, shrub mole-rat, large long-clawed mouse Fotografía de Chelemys megalonyx (Yamil Houssein http://www.jacobita.cl/) Reino: Animalia Orden: Rodentia Phyllum/División: Chordata Familia: Cricetidae Clase: Mammalia Género: Chelemys Sinonimia: Hesperomys megalonyx (Waterhouse, 1844), Oxymicterus scalops Gay, 1847, Oxymicterus niger Philippi, 1872, Notiomys megalonix (Waterhouse, 1844). Mann (1978) Tamayo & Frassinetti (1980). Nota Taxonómica: Esta especie incluye dos subespecies Chelemys megalonyx megalonyx (Waterhouse, 1844) y Chelemys megalonyx microtis (Philippi, 1900). Esta especie pertenece a un género en que la extensión de su diversidad específica es poco clara. Actualmente se considera que Chelemys incluye tres especies, para las que existen numerosas formas nominales (e.g., alleni , vestitus ) cuyos estatus no están adecuadamente evaluados. ANTECEDENTES GENERALES Aspectos Morfológicos Ratón de cuerpo regordete, con cola corta y hocico alargado y garras grandes. De coloración gris pardusca a marrón oscura, con el vientre blanco o gris claro. Mide 170-190 mm de largo total (de aspecto similar a Geoxus valdivianus pero de mayor tamaño). Cavícola. Mann (1978) Tamayo & Frassinetti (1980), Muñoz-Pedreros (2000), Ojeda et al 2005, Musser & Carleton (2005). Aspectos Reproductivos y Conductuales Sin información Alimentación (s ólo fauna) Sin información INTERACCIONE S RELEVANTES CON OTRAS ESPECIES Sin información Página 1 de 5 martes, 01 de diciembre de 2015 DISTRIBUCIÓN GEOGRÁFICA En Chile Chelemys megalonyx megalonyx desde la provincia de Elqui, en la región de Coquimbo a la región de Valparaíso. Chelemys megalonyx microtis desde el sur de la provincia de Valparaíso en región de Valparaíso hasta la provincia de Cautín en la región de La Araucanía. -

Appendix 1: Maps and Plans Appendix184 Map 1: Conservation Categories for the Nominated Property

Appendix 1: Maps and Plans Appendix184 Map 1: Conservation Categories for the Nominated Property. Los Alerces National Park, Argentina 185 Map 2: Andean-North Patagonian Biosphere Reserve: Context for the Nominated Proprty. Los Alerces National Park, Argentina 186 Map 3: Vegetation of the Valdivian Ecoregion 187 Map 4: Vegetation Communities in Los Alerces National Park 188 Map 5: Strict Nature and Wildlife Reserve 189 Map 6: Usage Zoning, Los Alerces National Park 190 Map 7: Human Settlements and Infrastructure 191 Appendix 2: Species Lists Ap9n192 Appendix 2.1 List of Plant Species Recorded at PNLA 193 Appendix 2.2: List of Animal Species: Mammals 212 Appendix 2.3: List of Animal Species: Birds 214 Appendix 2.4: List of Animal Species: Reptiles 219 Appendix 2.5: List of Animal Species: Amphibians 220 Appendix 2.6: List of Animal Species: Fish 221 Appendix 2.7: List of Animal Species and Threat Status 222 Appendix 3: Law No. 19,292 Append228 Appendix 4: PNLA Management Plan Approval and Contents Appendi242 Appendix 5: Participative Process for Writing the Nomination Form Appendi252 Synthesis 252 Management Plan UpdateWorkshop 253 Annex A: Interview Guide 256 Annex B: Meetings and Interviews Held 257 Annex C: Self-Administered Survey 261 Annex D: ExternalWorkshop Participants 262 Annex E: Promotional Leaflet 264 Annex F: Interview Results Summary 267 Annex G: Survey Results Summary 272 Annex H: Esquel Declaration of Interest 274 Annex I: Trevelin Declaration of Interest 276 Annex J: Chubut Tourism Secretariat Declaration of Interest 278 -

Check List and Authors Chec List Open Access | Freely Available at Journal of Species Lists and Distribution

ISSN 1809-127X (online edition) © 2010 Check List and Authors Chec List Open Access | Freely available at www.checklist.org.br Journal of species lists and distribution N Mammalia, Rodentia, Cricetidae, Irenomys tarsalis ISTRIBUTIO D gaps (Philippi, 1900): New records for Argentina and filling RAPHIC Gabriel M. Martin G EO G N O E-mail:Consejo [email protected] Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET) and Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia “San Juan Bosco”, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales Sede Esquel, Laboratorio de Investigaciones en Evolución y Biodiversidad. Sarmiento 849, CP 9200. Esquel, CH, Argentina. OTES N Abstract: Ten new records for the Chilean tree mouse, Irenomys tarsalis, are presented from western Argentina. This at least 125 km in western Chubut Province, where I. tarsalis was previously known for only three records. Additionally, environmentalrepresents a near information 30 % increase at an inecoregional the number and of habitatknown scalelocalities is provided. for the species in this country. Nine of them fill a gap of The Chilean tree mouse Irenomys tarsalis (Philippi, I. tarsalis specimens was made 1900) is a large rodent that inhabits the temperate following Pearson (1995) and by comparison with museum rainforests of southern Chile and adjacent Argentina specimensIdentification (MLP 11.VI.96.10,of MLP 29.IV.99.11), in which (Pearson 1983; 1995; Kelt 1993). Considered one of the combination of the following characters (including the rarest sigmodontines of the Southern Temperate exosomatic, craniomandibular and dental traits) can be Rainforests, the phylogenetic relationship of the species is considered diagnostic (see also Osgood 1943; Mann 1978; still debated and very little is known of its natural history Kelt 1993; Pearson 1995): rat-like in appearance with (Pardiñas et al. -

Intestinal Helminths in Wild Rodents from Native Forest and Exotic Pine Plantations (Pinus Radiata) in Central Chile

animals Communication Intestinal Helminths in Wild Rodents from Native Forest and Exotic Pine Plantations (Pinus radiata) in Central Chile Maira Riquelme 1, Rodrigo Salgado 1, Javier A. Simonetti 2, Carlos Landaeta-Aqueveque 3 , Fernando Fredes 4 and André V. Rubio 1,* 1 Departamento de Ciencias Biológicas Animales, Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias y Pecuarias, Universidad de Chile, Santa Rosa 11735, La Pintana, Santiago 8820808, Chile; [email protected] (M.R.); [email protected] (R.S.) 2 Departamento de Ciencias Ecológicas, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Chile, Casilla 653, Santiago 7750000, Chile; [email protected] 3 Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias, Universidad de Concepción, Casilla 537, Chillán 3812120, Chile; [email protected] 4 Departamento de Medicina Preventiva Animal, Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias y Pecuarias, Universidad de Chile, Santa Rosa 11735, La Pintana, Santiago 8820808, Chile; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +56-229-780-372 Simple Summary: Land-use changes are one of the most important drivers of zoonotic disease risk in humans, including helminths of wildlife origin. In this paper, we investigated the presence and prevalence of intestinal helminths in wild rodents, comparing this parasitism between a native forest and exotic Monterey pine plantations (adult and young plantations) in central Chile. By analyzing 1091 fecal samples of a variety of rodent species sampled over two years, we recorded several helminth Citation: Riquelme, M.; Salgado, R.; families and genera, some of them potentially zoonotic. We did not find differences in the prevalence of Simonetti, J.A.; Landaeta-Aqueveque, helminths between habitat types, but other factors (rodent species and season of the year) were relevant C.; Fredes, F.; Rubio, A.V. -

Ecology and Conservation of the Cactus Ferruginous Pygmy-Owl in Arizona

United States Department of Agriculture Ecology and Conservation Forest Service Rocky Mountain of the Cactus Ferruginous Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-43 Pygmy-Owl in Arizona January 2000 Abstract ____________________________________ Cartron, Jean-Luc E.; Finch, Deborah M., tech. eds. 2000. Ecology and conservation of the cactus ferruginous pygmy-owl in Arizona. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-43. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 68 p. This report is the result of a cooperative effort by the Rocky Mountain Research Station and the USDA Forest Service Region 3, with participation by the Arizona Game and Fish Department and the Bureau of Land Management. It assesses the state of knowledge related to the conservation status of the cactus ferruginous pygmy-owl in Arizona. The population decline of this owl has been attributed to the loss of riparian areas before and after the turn of the 20th century. Currently, the cactus ferruginous pygmy-owl is chiefly found in southern Arizona in xeroriparian vegetation and well- structured upland desertscrub. The primary threat to the remaining pygmy-owl population appears to be continued habitat loss due to residential development. Important information gaps exist and prevent a full understanding of the current population status of the owl and its conservation needs. Fort Collins Service Center Telephone (970) 498-1392 FAX (970) 498-1396 E-mail rschneider/[email protected] Web site http://www.fs.fed.us/rm Mailing Address Publications Distribution Rocky Mountain Research Station 240 W. Prospect Road Fort Collins, CO 80526-2098 Cover photo—Clockwise from top: photograph of fledgling in Arizona by Jean-Luc Cartron, photo- graph of adult ferruginous pygmy-owl in Arizona by Bob Miles, photograph of adult cactus ferruginous pygmy-owl in Texas by Glenn Proudfoot. -

DIET CHANGES in BREEDING TAWNY OWLS &Lpar;<I>Strix Aluco</I>&Rpar;

j Raptor Res. 26(4):239-242 ¸ 1992 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. DIET CHANGES IN BREEDING TAWNY OWLS (Strix aluco) DAVID A. KIRK 1 Departmentof Zoology,2 TillydroneAvenue, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen,Scotland, U.K. AB9 2TN ABSTVO,CT.--I examinedthe contentsof Tawny Owl (Strix alucosylvatica) pellets, between April 1977 and February 1978, in mixed woodlandand gardensin northeastSuffolk, England. Six mammal, 14 bird and 5 invertebratespecies were recordedin a sample of 105 pellets. Overall, the Wood Mouse (Apodemussylvaticus) was the most frequently taken mammal prey and the House Sparrow (Passer domesticus)was the mostfrequently identified bird prey. Two typesof seasonaldiet changewere found; first, a shift from mammal prey in winter to bird prey in the breedingseason, and second,a shift from smallprey in the winter to medium-sized(> 30 g) prey in the breedingseason. Contrary to somefindings elsewherein England, birds, rather than mammals, contributedsignificantly to Tawny Owl diet during the breedingseason. Cambiosen la dieta de bfihosde la especieStrix alucodurante el periodode reproduccibn EXTRACTO.--Heexaminado el contenidode egagrbpilasdel bfiho de la especieStrix alucosylvatica, entre abril de 1977 y febrerode 1978, en florestasy huertosdel norestede Suffolk, Inglaterra. Seismamlferos, catorceaves y cincoespecies invertebradas fueron registradosen una muestrade 105 egagrbpilas.En el total, entre los mamlferos,el roedorApodemus sylvaticus fue el que conmils frecuenciafue presade estos bfihos;y entre las aves,la presaidentificada con mils frecuenciafue el gorribnPasser domesticus. Dos tipos de cambib en la dieta estacionalfueron observados:primero, un cambib de clase de presa: de mamlferosen invierno a la de avesen la estacibnreproductora; y segundo,un cambiben el tamafio de las presas:de pequefiasen el inviernoa medianas(>30 g) en la estacibnreproductora. -

Ketupa Zeylonensis) Released More Than a Decade After Admission to a Wildlife Rescue Centre in Hong Kong SAR China

Survivorship and dispersal ability of a rehabilitated Brown Fish Owl (Ketupa zeylonensis) released more than a decade after admission to a wildlife rescue centre in Hong Kong SAR China The Brown Fish Owl, Sam, in captivity at Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden April 2008 Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden Publication Series: No 3 Survivorship and dispersal ability of a rehabilitated Brown Fish Owl (Ketupa zeylonensis) released more than a decade after admission to a wildlife rescue centre in Hong Kong SAR China Authors Rupert Griffiths¹ and Gary Ades ¹Present Address: The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, West Hatch Wildlife Centre, Taunton, Somerset, TA 35RT, United Kingdom Citation Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden. 2008. Survivorship and dispersal ability of a rehabilitated Brown Fish Owl (Ketupa zeylonensis) released more than a decade after admission to a wildlife rescue centre in Hong Kong SAR China. Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden Publication Series No.3. Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden, Hong Kong Special Adminstrative Region. Copyright © Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden Corporation Lam Kam Road, Tai Po, N.T. Hong Kong Special Adminstrative Region April 2008 ii CONTENTS Page Execuitve Summary 1 Introduction 2 Methodology 3 Results 4 Discussion 4 Acknowledgments 5 References 5 Table 7 Figures 8 iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A Brown Fish Owl (Ketupa zeylonensis) which had been maintained in captivity at Kadoorie Farm & Botanic Garden, for 11 years following its rescue, was released at a site in Sai Kung in Hong Kong on 28th November 2003. Post-release monitoring was carried out and the bird was confirmed to have survived for at least 3 months before the radio-transmitter was dropped. -

CALIFORNIA SPOTTED OWL (Strix Occidentalis Occidentalis) Jeff N

II SPECIES ACCOUNTS Andy Birch PDF of California Spotted Owl account from: Shuford, W. D., and Gardali, T., editors. 2008. California Bird Species of Special Concern: A ranked assessment of species, subspecies, and distinct populations of birds of immediate conservation concern in California. Studies of Western Birds 1. Western Field Ornithologists, Camarillo, California, and California Department of Fish and Game, Sacramento. California Bird Species of Special Concern CALIFORNIA SPOTTED OWL (Strix occidentalis occidentalis) Jeff N. Davis and Gordon I. Gould Jr. Criteria Scores Population Trend 10 Range Trend 0 Population Size 7.5 Range Size 5 Endemism 10 Population Concentration 0 Threats 15 Year-round Range Winter-only Range County Boundaries Water Bodies Kilometers 100 50 0 100 Year-round range of the California Spotted Owl in California. Essentially resident, though in winter some birds in the Sierra Nevada descend to lower elevations, where, at least to the south, small numbers of owls also occur year round. Outline of overall range stable but numbers have declined. California Spotted Owl Studies of Western Birds 1:227–233, 2008 227 Studies of Western Birds No. 1 SPECIAL CONCERN PRIORITY occurrence: one along the west slope of the Sierra Nevada from eastern Tehama County south to Currently considered a Bird Species of Special Tulare County, the other in the mountains of Concern (year round), priority 2. Included on southern California from Santa Barbara, Ventura, the special concern list since its inception, either and southwestern Kern counties southeast to together with S. o. caurina (Remsen 1978, 2nd central San Diego County. Elevations of known priority) or by itself (CDFG 1992). -

<I>STRIX ALUCO</I>

j Raptor Res. 28(4):246-252 ¸ 1994 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. DIET OF URBAN AND SUBURBAN TAWNY OWLS (STRIX ALUCO) IN THE BREEDING SEASON ANDRZEJ ZALEWSKI Mammal ResearchInstitute, Polish Academy of Sciences,77-230 Biatowieœa, Poland ABSTI•CT.--The diet of tawny owls (Strix aluco)was studiedduring the breedingseasons 1988-90 in an urbanand a suburbanarea in Torufi, Poland.Two amphibian,18 bird,and 14 mammalspecies were recordedas prey in a sampleof 312 pellets.From 600 prey itemsfound in bothsites, the housesparrow (Passerdomesticus) was the mostfrequently taken bird prey and the commonvole (Microtus arvalis) the mostfrequently taken mammal prey. Significantlymore mammals than birdswere taken at the suburban sitethan at the urbansite (P < 0.001). At the urbansite, the proportionof birds(except for tits [Parus spp.]and housesparrows) increased over the courseof the breedingseason, while the proportionof Apodemusspp. decreased.Similarly, at the suburbansite the proportionof all birds increasedand the proportionof Microtusspp. decreased. House sparrows at the urban site and Eurasiantree sparrows (Passermontanus) and tits at the suburbansite were takenin higherproportion than their availability. An examinationof dietarystudies from elsewhere in Europeindicated that therewas a positivecorrelation betweenmean prey sizeand increasingproportion of birdsin tawny owl diets(P = 0.003). KEY WORDS: tawnyowl; diet;urban and rural area;bird selection;prey-size selection. Dieta de Strixaluco urbano y suburbanoen la estaci6nreproductiva RESUMEN.--Seestudi6 la dietade Strixaluco durante las estacionesreproductivas de 1988 a 1990 en un fireaurbana y suburbanaen Torun, Polonia.Dos antibios, 18 avesy 14 especiesde mam•ferosfueron registradoscomo presa en una muestrade 312 egagr6pilas.De 600 categorlasde presasencontradas en ambossitios, Passer domesticus rue el ave-presamils frecuentejunto al mfimfferoMicrotus arvalis. -

Seasonal Changes in Tawny Owl (Strix Aluco) Diet in an Oak Forest in Eastern Ukraine

Turkish Journal of Zoology Turk J Zool (2017) 41: 130-137 http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/zoology/ © TÜBİTAK Research Article doi:10.3906/zoo-1509-43 Seasonal changes in Tawny Owl (Strix aluco) diet in an oak forest in Eastern Ukraine 1, 2 Yehor YATSIUK *, Yuliya FILATOVA 1 National Park “Gomilshanski Lisy”, Kharkiv region, Ukraine 2 Department of Zoology and Animal Ecology, Faculty of Biology, V.N. Karazin Kharkiv National University, Kharkiv, Ukraine Received: 22.09.2015 Accepted/Published Online: 25.04.2016 Final Version: 25.01.2017 Abstract: We analyzed seasonal changes in Tawny Owl (Strix aluco) diet in a broadleaved forest in Eastern Ukraine over 6 years (2007– 2012). Annual seasons were divided as follows: December–mid-April, April–June, July–early October, and late October–November. In total, 1648 pellets were analyzed. The most important prey was the bank vole (Myodes glareolus) (41.9%), but the yellow-necked mouse (Apodemus flavicollis) (17.8%) dominated in some seasons. According to trapping results, the bank vole was the most abundant rodent species in the study region. The most diverse diet was in late spring and early summer. Small forest mammals constituted the dominant group in all seasons, but in spring and summer their share fell due to the inclusion of birds and the common spadefoot (Pelobates fuscus). Diet was similar in late autumn, before the establishment of snow cover, and in winter. The relative representation of species associated with open spaces increased in winter, especially in years with deep snow cover, which may indicate seasonal changes in the hunting habitats of the Tawny Owl. -

Past and Present Small Mammals of Isla Mocha (Chile)

Mamm. biol. 68 (2003) 365±371 Mammalian Biology ã Urban & Fischer Verlag http://www.urbanfischer.de/journals/mammbiol Zeitschrift fuÈr SaÈ ugetierkunde Original investigation Past and present small mammals of Isla Mocha (Chile) By BAÂRBARA SAAVEDRA,D.QUIROZ, and J. IRIARTE Departamento de Ciencias EcoloÂgicas, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile Receipt of Ms. 14. 06. 2002 Acceptance of Ms. 07. 10. 2002 Abstract We describe archaeozoological and extant small mammals from Isla Mocha, an island located in south-central Chile. Species composition was compared among past and present assemblages. Also composition, as well as individual and population parameters were compared among island habi- tats. Specimens from archaeological sites included Oligoryzomys longicaudatus, Abrothrix sp., and Octodon pacificus, whereas Abrothrix longipilis, A. olivaceus, Oligoryzomys longicaudatus,and Geoxus valdivianus were captured. Higher richness was observed in intermediate-disturbed habitat. Body size and tail length, as well as body mass did not vary among island habitats for A. longipilis or A. olivaceus. Higher abundance was associated to less perturbed habitat. Key words: Octodon pacificus, archaeozoology, Isla Mocha, Chile Introduction Islands comprise an important part of the 1999). The forest on Isla Mocha is domi- Chilean territory. Despite this, little ecologi- nated by Aextoxicon and members of the cal research has been done in these ecosys- Myrtaceae. Botanical, geological, and geo- tems. One exception is Isla Mocha, one of graphical descriptions suggest that the is- the few islands that have been surveyed for land has had similar vegetation conditions its fauna, vegetation, and archaeology. One as at present since at least 1,760 years BP remarkable mammal is Octodon pacificus (Lequesne et al. -

Diet and Activity Patterns of Leopardus Guigna in Relation To

DIET AND ACTIVITY PATTERNS OF LEOPARDUS GUIGNA IN RELATION TO PREY AVAILABILITY IN FOREST FRAGMENTS OF THE CHILEAN TEMPERATE RAINFOREST A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Stephania Eugenia Galuppo Gaete IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE Ron Moen September 2014 © Stephania Eugenia Galuppo Gaete 2014 Acknowledgements I want to thank first people from Chile: Constanza Napolitano (the first stone) Elke Shüttler, Pepe Llaipén, Thora Herrmann, Lisa Söhn, Aline Nowak, Nicolás Gálvez, Felipe Hernández, Jerry Laker, Katherine Hermosilla, Tito Petitpas and the rest of the Kod Kod team, the community of Quetroleufu, specially the Mariñanco family, Marianela Rojas for all the paperwork, and of course my mother, grandmother and brother. I also want to thank the United States people, Gary and Leslie, first of all for their generous support in all the stages of this process, all of our friends from CSCC, Gustavo Rodrigues Oliveira-Santos for the advice, and the thesis family (words are not needed) Rodrigo and Santino for all of the rising early, the trapping, the work in the field in the front and the back of the screen and the love and support even in the smallest detail in all the process. I would like to thank dear friend, Brandon Breen, who provided a lot of positive energy. Finally I would like to thank my committee, Ron Moen, my advisor for his understanding in all my emotional stages and for his generosity, James Forester, you were always there, but I underutilized your help, and Rob Blair, who served on my committee.